An assessment of how current Administration polices regarding immigration and removals are affecting the agricultural sector (October 2):

Agricultural employers, who have been incentivized to utilize illegal aliens for numerous reasons including the excessively high FLS-based AEWR, will imminently face severe challenges accessing a sufficient and legal supply of labor to sustain current food production levels. According to the Department’s National Agricultural Worker Survey (NAWS),[66] agricultural employers are disproportionately and increasingly dependent on illegal aliens with approximately 42 percent of crop workers surveyed reported lacking authorization to work in the United States during FY 2021-2022; compared to 36 percent in FY 2017-2018. These workers, both illegal aliens and authorized U.S. crop workers, are also settled and relatively immobile. Data from NAWS further shows that, in 2021-2022, only 3 percent of all U.S. crop workers reportedly migrated by following the crops while 84 percent of these workers remain settled and did not migrate for work at all. U.S. crop workers are also aging, as approximately 36 percent of the crop workers interviewed were 44 years of age or older, compared to less than 15 percent in 2000, and they spent an average of 8 years working for the same employer, compared to 3 years in 2000.

In short, the agricultural sector is experiencing acute labor shortages and instability because it has long depended on a workforce with a high proportion of illegal aliens who previously cycled in and out of the U.S. through a porous border; now, however, those who might have cycled in cannot do so because of the now secure U.S. Southern Border. Further, the remaining workforce tends to be relatively immobile and unable to adjust quickly to shifting labor demands, resulting in significant disruptions to farmers’ ability to meet seasonal labor needs.

Most concerning for the fragile agricultural workforce are the dwindling numbers of current U.S. crop workers who are planning to continue working in agriculture. According to the NAWS, just over one in every five U.S. crop workers surveyed were planning to remain in agriculture for up to 5 years, while approximately 53 percent reported that they could find a non-farm job within one month. Separately, with illegal border crossings at historic lows. Agricultural employers that have historically relied on such illegal aliens, are experiencing economic harm caused by mounting labor shortages. According to available studies, a hypothetical decision to heighten immigration enforcement actions could further reduce the supply of agricultural labor with an estimated loss of, at a relatively modest estimate, 225,000 [67] agricultural workers.[68]

In addition, the Department does not believe American workers currently unemployed or marginally employed will make themselves readily available in sufficient numbers to replace large numbers of aliens no longer entering the country, voluntarily leaving, or choosing to exit the labor force due to the self-perceived potential for their removal based on their illegal entry and status. The supply of American agricultural workers is limited by a range of structural factors including the geographic distribution of agricultural operations, the seasonal nature of certain crops, and overall unemployment rate.[69] Furthermore, agricultural work requires a distinct set of skills and is among the most physically demanding and hazardous occupations in the U.S. labor market. These essential jobs involve manual labor, long hours, and exposure to extreme weather conditions—particularly in the cultivation of fruit, tree nuts, vegetables, and other specialty crops for which production cannot be immediately mechanized. Based on the Department’s extensive experience administering the H-2A temporary agricultural visa program, the available data strongly demonstrates—a persistent and systemic lack of sufficient numbers of qualified, eligible and interested American workers to perform the kinds of work that agricultural employers demand. In the most recent five years, for example, employer demand for H-2A workers has increased by 36 percent from 286,900 workers requested in FY 2020 to nearly 391,600 workers requested in FY 2024, and the Department has consistently certified at least 97 percent of employer demand for agricultural workers based on a lack of qualified, eligible, and interested U.S. workers. For FY 2025 and as of July 1, 2025, employers seeking H-2A workers have requested more than 320,700 worker positions and the Department has certified 99 percent of the demand based on a lack of qualified and eligible U.S. workers. Despite efforts to broadly advertise agricultural jobs, as required by the Department’s regulations at 20 CFR 655.144, 150, 153, and 154, the most recent data confirm that domestic applicants are not applying for agricultural positions in sufficient numbers to meet the temporary or seasonal workforce needs of employers. Thus, based on the available evidence, the Department concludes that qualified and eligible U.S. workers, whether unemployed, marginally employed, or employed seeking work in agriculture, will not make themselves immediately available in sufficient numbers to avert the irreparable economic harm to agricultural employers who no longer have access to a ready pool of illegal aliens to fulfill their labor needs.

2. Economic Forecasting Regarding Food Prices and Availability

With the historic near total cessation of illegal border crossings—the Department must take immediate action to provide agricultural employers with a viable workforce alternative while concurrently averting imminent economic harm. Labor shortages can have an immediate effect on farm operations. For example, one study found that a mere 10 percent decrease in the agricultural workforce can lead to as much as a 4.2 percent drop in fruit and vegetable production and a 5.5 percent decline in farm revenue.[70] Given that approximately 42 percent of the U.S. crop workforce are unable to enter the country, potentially subject to removal or voluntarily leaving the labor force, these impacts will likely be dramatically higher. The study further estimated that a 21 percent shortfall in the agricultural workforce would result in an overall $5 billion loss just in terms of domestic fresh produce alone for U.S. consumers. Such significant economic impacts not only create tangible and imminent economic harms, but they structurally disrupt the ordinary operations of the U.S. agricultural sector, resulting in shortages of agricultural commodities that cannot be supplemented with imports in the near-term.

Given the scale, speed, and investment in the federal government’s efforts to enforce immigration laws and restore the integrity of the U.S. border, the Department concludes that there will be significant labor market effects in the agricultural sector, which has long been pushed to depend on a workforce with a high proportion of illegal aliens. Because these illegal aliens often possess specialized skills suited to agricultural tasks and typically earn lower wages than authorized workers, their sudden and large-scale departure is expected to significantly increase labor costs for employers. These cost increases are very likely to limit the ability of agricultural operations to maintain current production levels or expand employment, resulting in downstream impacts on food supply and pricing. [emphasis added by MDC]

From Federal Register, filed by DoL, October 2, 2025. (h/t WaPo), i.e., the Trump Administration.

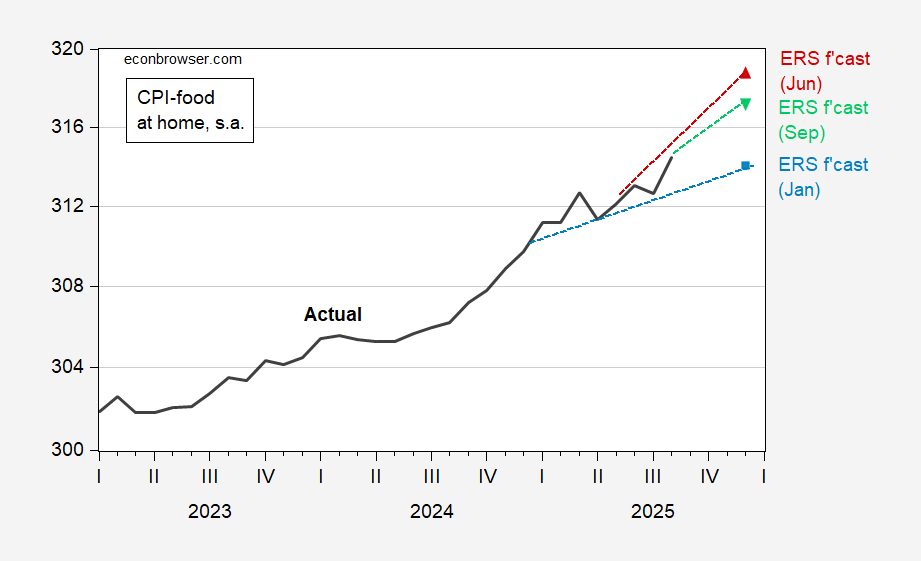

Here’s the evolution of grocery prices through August (we won’t get September numbers until October 24), plus the September 25 forecast from ERS.

Figure 1: CPI for food at home (black), USDA Economic Research Service forecast from January (blue square), from June (red triangle), from September (green inverted triangle), on log scale. Source: BLS via FRED, ERS, author’s calculations.

“…incentivized to utilize illegal aliens for numerous reasons including the excessively high FLS-based AEWR, will imminently face severe challenges accessing a sufficient and legal supply of labor to sustain current food production levels.”

“Incentivized” is an interesting way to say “break the law to increase profits”. Much of the argument in this text is that there aren’t enough workers to staff food production, after starting off by excusing the hiring of illegals by saying legal workers visas require paying minimum wages. Yet another indictment of those who hire illegal immigrants, with no attempt to punish them.

Also, I’m not saying the bit I quoted is the gassiest writing in the entire text, but seriously, kids, don’t write like that.

This situation didn’t happen overnight. Back 50-years ago, there were plenty of migrant workers who followed the planting and harvesting and then went south for the winter. Gradually, as the US “social safety net” expanded to include everyone inside the US, there became an incentive to simply ignore all of the legal temporary worker processes and go directly to Go and collect $200 … just walk into the US, head to a city, and set up residence with the assurance that you could walk into an emergency room if yo became ill and get financial assistance if you didn’t work. Only fools go looking for work on the farm.

https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/The_road_to_hell_is_paved_with_good_intentions

Wrong, as always. Very little of the U.S. social safety net is available yo illegal immigrants. This is a right-wing talking point, and like so many right-wing talking points, is a lie.

Social Security retirement benefits aren’t available to illegal immigrants. Neither are disability payments. Medicare is not available to illegal immigrants, nor is Medicaid. Unemployment insurance is not available to illegal immigrants.

Emergency medical care is available to all, and food stamp programs generally don’t consider immigration status, but have limited avaiability.

Brucie, why do you keep lying here? I understand that you might choose to lie in places where your lies haven’t been exposed repeatedly, but why here? Go, spread your slime in yheright-wing echo chamber. Heck, you’ll be praised for lying there. Why here?

“Back 50-years ago, there were plenty of migrant workers who followed the planting and harvesting and then went south for the winter. ”

families formed and kids needed to go to school. if mom or dad are on the other side of the country working half the year, how does that contribute to conservative family values bruce? how does a child receive a good education if they are uprooted to a new school every 6 months? bruce, you are advocating for a policy and life that is certainly not family valued.

Bruce Hall As Macroduck pointed out, immigrants are not eligible for “safety net” programs. But it seems that the heart of your objection is that migrant workers are staying here longer and getting nonfarm jobs that allow them to collect $200 and Go. To the extent that that’s true, we should be thankful. Migrants leaving low value of marginal product jobs in the fields and getting higher value of marginal product jobs is exactly what we want to happen.

BTW, I doubt that you’ll read this because you tend to do some drive-by posting and hide for a few weeks after your nonsense and economic illiteracy have been exposed.