At the economics meetings here in San Diego this weekend, I learned about some very interesting new research on one of the core questions in finance and macroeconomics that had long puzzled me.

Category Archives: financial markets

U.S. government profits from AIG bailout

A key player in the financial crisis was insurance giant AIG, which sold a huge volume of credit default swaps supposedly protecting buyers of mortgage-backed securities from losses due to default. But AIG had nowhere near the capital necessary to honor these guarantees when things went bad, and much of AIG’s liabilities ended up being picked up by the Fed and the Treasury. On Tuesday the U.S. Treasury announced that it had sold the last of the common shares in AIG that it had acquired as compensation for its emergency assistance to AIG and reported that the Treasury and the Fed had together earned a profit of $22.7 billion as a result of their assistance to AIG. I was curious to take a look at how this story ended up having a happy ending.

Links for 2012-11-10

A few links to some items I found of interest.

Lost Decades: Two Years Later

The paperback edition of Lost Decades (W.W. Norton) is to be officially released October 1st. This seems as appropriate a juncture as any to assess the predictions Jeffry Frieden and I wrote almost two years ago.

Fat fingers and the price of oil

Can the wild swings in the price of oil over the last few weeks have anything to do with supply and demand?

The Federal Reserve’s Maturity Extension Program and Treasury debt management

The Fed giveth and the Treasury taketh away.

Crowding Out Watch: July 2012

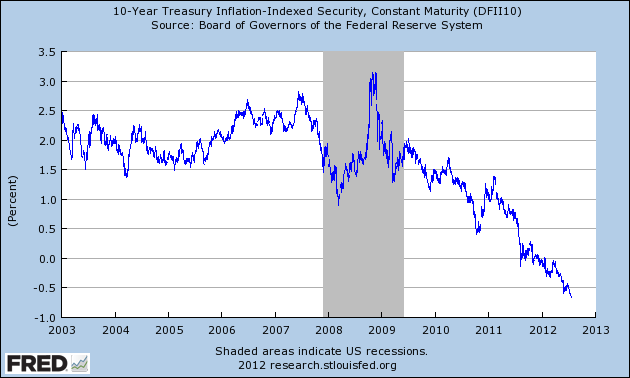

As feared by Representative Ryan, in March 2011, crowding out due to deficits: The ten year inflation adjusted constant maturity rate as of 7/20 was -0.67%

Source: St. Louis Fed FRED accessed 7/24 11am Pacific.

Would Regulation of Libor Have Passed Senator Shelby’s Benefit-Cost Analysis?

Senator Shelby, Ranking Republican of the Banking Committee, has sponsored The Financial Regulatory Responsibility Act, which seeks to restrict implementation of Dodd-Frank, and require benefit-cost analysis for financial regulation. To quote Sen. Shelby: “American job creators are under siege from the Dodd-Frank Act.” [1] Now, it’s clear that British authorities have primary responsibility for regulating Libor (after all, the “L” in Libor stands for “London”). But I think it’s useful to consider this question because clearly similar concerns will arise in markets in the US sometime in the future.

Europe in 1931

I was at a conference at the Cato Institute two weeks ago discussing some research by Dartmouth Professor Doug Irwin on the role of the gold standard in the Great Depression of 1929-1933. If you’re interested, you can see a written version of my comments, the slides from my presentation, or a video of the session (my comments begin a little more than half way in). Here I’d like to relate some of the discussion of what happened in Europe in 1931, and comment on some of the parallels with what is going on today.

Options for Europe

This problem is not fixing itself.