From Bloomberg:

The yuan strengthened after China’s central bank raised its fixing for a fourth day and data showed a less-than-estimated drop in the nation’s foreign-exchange reserves.

The currency stockpile shrank by $28.6 billion last month, the smallest decline since June, to $3.2 trillion, the People’s Bank of China said on Monday. That’s lower than the $40.9 billion decrease predicted in a Bloomberg survey of economists, and compares with December’s record drop of $108 billion as the monetary authority supported the yuan.

Context

As previously noted, Chinese policymakers have been navigating the trilemma — the proposition that one can only fully achieve two of three goals of exchange rate stability, monetary autonomy and financial openness.

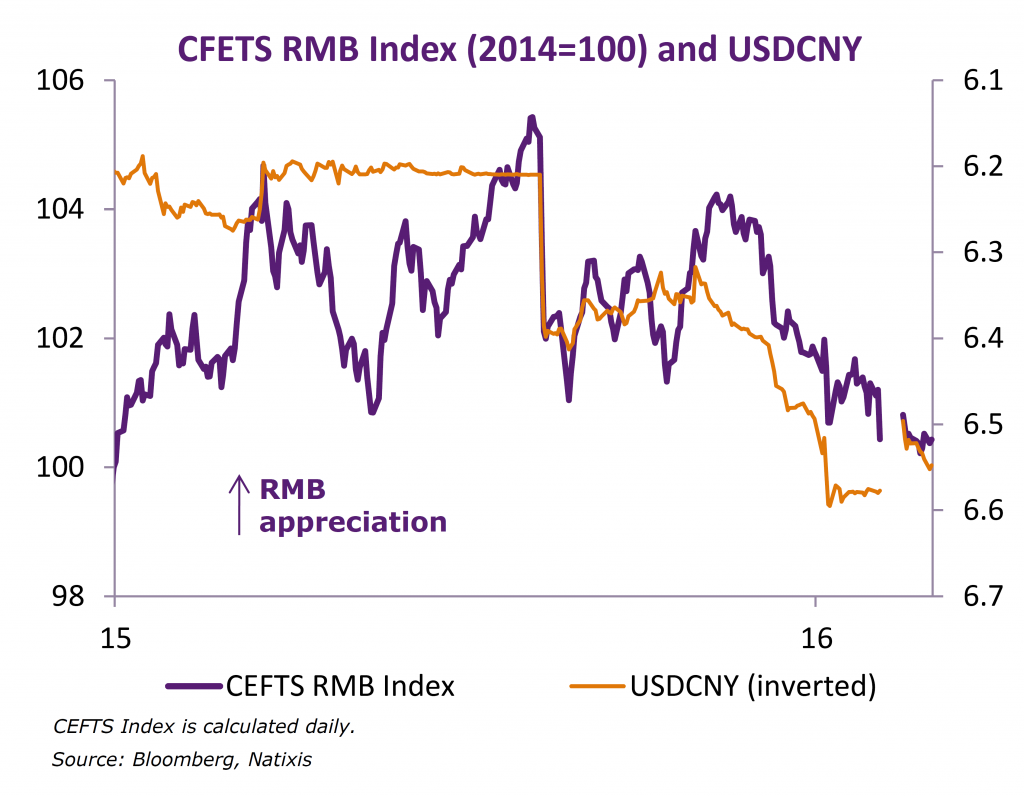

The exchange rate has depreciated over time against the reference basket of currencies, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: “While CNY appreciated against USD it remained flat against the CFETS currency basket,” from Natixis Economic Research, March 1, 2016.

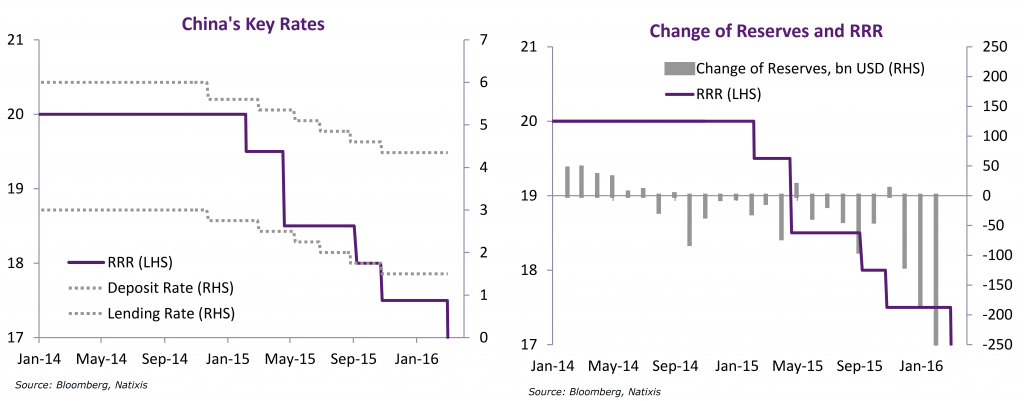

At the same time, the PBoC is attempting to stimulate the economy — by dropping policy rates and reducing bank required reserve ratios — without further depreciating the currency. These policy actions are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: “One more RRR cut to replenish liquidity from loss of FX reserves,” from Natixis Economic Research, March 1, 2016.

Achieving the goal of autonomous monetary policy (in order to sustain growth) can be accomplished by either further currency depreciation, or tightening capital controls. The extent to which a combination of these policies will have to be pursued depends in part on how much capital outflow persist, with some observers holding apocalyptic views (e.g., “people are panicked”). On this count, McCauley and Shu provide a more nuanced view of the source of outflows.

Persistent private capital outflows from China since June 2014 have led to two different narratives. One tells a story of investors selling mainland assets en masse; the other of Chinese firms paying down their dollar debt. Our analysis favours the second view, but also points to what both narratives miss – the shrinkage of offshore renminbi deposits.

Our approach, presented in the September 2015 BIS Quarterly Review, starts from the BIS international banking statistics reported by banks outside China. This contrasts with other analyses which typically take changes in official foreign reserves (plus current account surplus) as capital outflows, which require complicated estimation of valuation and other adjustments. To understand the cross-border outflow of capital in the BIS data, we follow the money from declining offshore renminbi deposits in East Asia and declining foreign currency loans at banks in mainland China, as reported by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC). In addition, we exclude from the BIS data PBoC deposits with overseas banks, using new data consistent with the IMF’s special data dissemination standard (SDDS).

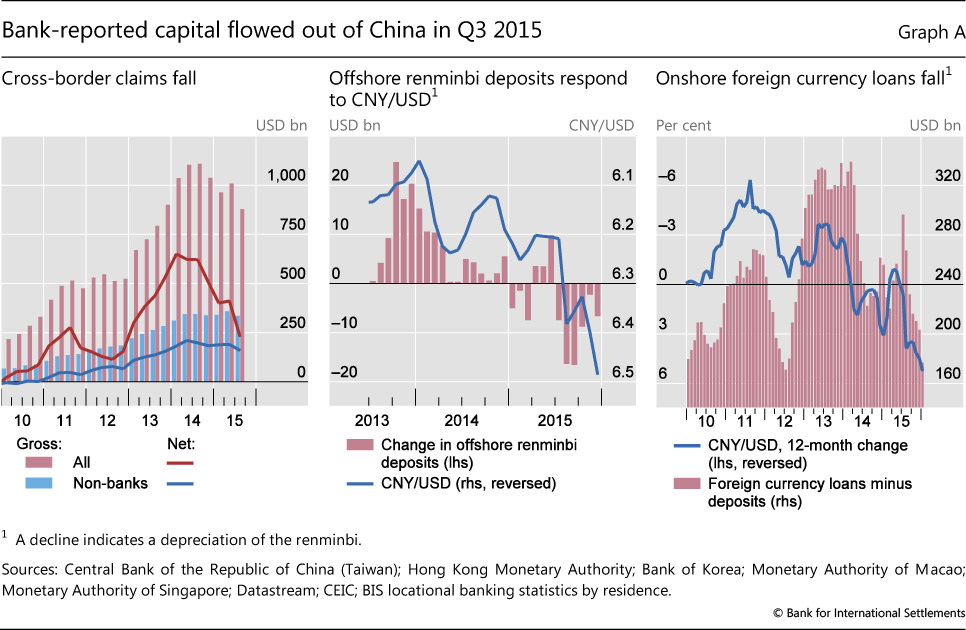

McCauley and Shu highlight the trends in these banking data in a series of graphs.

Source: McCauley and Shu (2016).

They conclude:

To recap, our analysis suggests that recent outflows from China can be explained, to a large extent, by continued shrinkage of the offshore renminbi market and Chinese firms’ paydown of net foreign currency debt. The PBoC’s declared intention to keep the renminbi stable in effective terms would imply a weaker renminbi against the dollar were the dollar to appreciate against major currencies. In this event, offshore depositors might not hold onto maturing renminbi deposits and Chinese firms would still have reason to repay dollar-denominated debt.

Of course, just because these factors have been the primary driver of capital outflows in the past doesn’t mean they will continue to be. Moreover, the hit to the trade balance as exports fell in February will, if repeated, add a new strain on forex reserves (as well as growth).

An Observation on “The” Money Supply

As noted previously, the PBoC has reduced policy rates and reduced reserve requirements. It’s interesting to note that M0 (essentially money base, or high powered money) growth has flattened out even as M1 growth has accelerated. This, combined with fairly steady M2 growth (and tighter capital controls), suggests to me that part of these policy moves are aimed at offseting the contractionary effects of forex reserve holding, rather than depreciating the currency.

(For additional reasons why depreciation might not be desirable from the Chinese policymakers’ views, see here).

Yes, in dollar terms, exports fell a whopping 25.4% in February, with big hits coming to steel, IT, vehicles, textiles, furniture, garments and footwear.

Also, I think it’s important to keep in mind that much of the capital flight appears to be coming off the current, not the capital, account with ‘over-invoicing’ (or over-payment, if you prefer) accounting for an apparent $450 bn of capital flight in 2015. See Balding piece, here:

http://www.baldingsworld.com/2016/03/01/follow-up-to-whether-china-has-a-trade-surplus/

Also, of course, the BIS analysis is five months out of date.

Steve Kopits: Actually, if one reads the text, one will see some of the data extends to Nov/Dec 2015.

Yes, second two graphs. The section is somewhat mislabeled.

More importantly, though, you should respond to Balding’s article. This is what has been passed around in the hedge fund world in the last few days.

Steve Kopits: Well, I accept there is capital flight through mis-invoicing, as detailed in this Econbrowser post. Kinda old news, isn’t it? Also, the underlying Deutsche Bank Special report circulated 2/29 stated:

I’m not sure exactly how this is make me revise my views. In fact the results by Cheung et al. suggest that if the authorities are able to stabilize depreciation expectations, then outflows (however measured) will stabilize.

Yes, if the capital flight is coming from fears of devaluation.

Is it? I’ve spoke to a number of Chinese in the last week, and they are very concerned about political developments in China, specifically with respect to the policies of President Xi. We have a kind or purge and terror regime running through China now, and the Chinese I spoke to said it’s running straight through their companies (SOE’s). People are afraid.

How do you create the confidence to handle a downturn even as the President is ramping up all kinds of repression? How does banning the foreign media from China, starting March 10, create confidence in this government?

As I see it, either Xi wins, and then the China we know is over. Or Xi loses, and then I suspect the Communist era in China is over, even if the Communist Party remains in power nominally.

Purge or Terror? That is China since the beginning of time. Capital flight is due to the end of industrial expansion.

When you say they are “stimulating” the economy, you mean the consumer side. The industrial side will be in a permanent contraction for the new few years.

No. Xi is different.

The capital flight is not necessarily driven by expectations of devaluation, but by lack of expectations of appreciation — there is a decade long carry trade unwinding.

Then there is the natural desire of savers in an authoritarian, corrupt emerging market to diversify, fuelled by the so called anti-corruption (anti-Xi) threats.

Outflows should continue, and the resulting positive NIIP will be good for China. Capital controls seem just to porous and will increase corruption and cronyism further.

Ah, a clue about collapsing exports. From the WSJ:

“Chinese officials are trying anew to slow a money exodus from the country, clamping down on individuals seeking to flee the yuan and making life tougher for companies that need to trade the currency for dollars to do business.

China’s foreign-exchange regulator in recent months has deployed a new system to monitor individual purchases of foreign funds and has asked banks to reduce foreign-currency transactions. It has summoned bankers to its offices to give guidance and has grilled them when foreign-exchange activity spikes, according to executives at Chinese and foreign lenders.

Banks, in turn, have increased scrutiny of foreign-currency transactions by businesses ranging from Chinese entrepreneurs investing abroad to companies paying overseas bills.

A European chemicals manufacturer recently faced delays in Shanghai in obtaining U.S. dollars, threatening its deadline for an overseas licensing payment. The Bank of Tianjin is having trouble getting funds from mainland investors for a planned Hong Kong public stock offering. A water-treatment company struggled to withdraw $2,000 for an engineer to travel to the U.S.

“There appears to be a real crackdown on money flowing out of China,” said Jean Francois Harvey, global managing partner at Hong Kong law firm Harvey Law Corp., whose clients have had difficulty recently transferring money out of China for equipment purchases and investment. “Even normal business transactions which are ongoing are getting delayed.””

See the whole story here: http://www.wsj.com/articles/china-fighting-money-exodus-squeezes-business-1457475908

It will be useful ( and a nice PhD project) to see if China can disprove the proposition that one can only fully achieve two of three goals of exchange rate stability, monetary autonomy and financial openness. Based on their track record I’m betting that they can.

As to the previous comment (“I’ve spoke to a number of Chinese in the last week, and they are very concerned about political developments in China, specifically with respect to the policies of President Xi. We have a kind or purge and terror regime running through China now, and the Chinese I spoke to said it’s running straight through their companies (SOE’s). People are afraid”.) I’m just back from China and I found support for that statement. But the people I spoke to there – and those expat Chinese I’ve spoken to since – attribute the ‘terror’ to the ongoing anti-corruption drive coupled with a publicly discussed proposal to trim the ‘deadwood’ from the Party.

The anticorruption drive has revealed vast numbers of Party members who have contributed nothing to the country or the Party, and who seem to be cynical careerists. Xi has apparently floated the idea of cancelling their Party memberships – as many as 30,000,000 of them. To be kicked out of the elite, publicly, would feel like reading in the Times that you’re being kicked off MOMA’s board of directors for being unhelpful and unproductive. Seriously, it’s a huge social loss of face.

It sounds like Phase 2 of the anticorruption drive is to weed out those corrupted by cynicism and careerism. What a concept!

So that’s been the standard narrative: Freedom through absolutism. If only Xi wins absolute power, corruption can be defeated. Like most Chinese, I have some sympathy for this view.

However, go to your mother, and say, “See, China will be free if a totalitarian regime is successfully installed.” See if you can say it with a straight face.

More seriously, we would want to test the assertion empirically. What evidence of reforms do we see? And the answer is not that much. If you’ve worked in a post-socialist county, as I have, you know that corruption is a principal-agent problem. Addressing it requires an understanding of pay and incentives, as well as a systems approach to reduce the opportunity for bribery. For someone interested in reform, I’d expect to be reading about, say, IBM and McKinsey working to migrate building permits to an internet-based system with a blind referee, etc. I’d expect to see a lot of process and systems stories in the press. I can’t find very much.

Further, as countries become more wealthy, power is delegated downward. That’s a condition of wealth. If you have to wait for me to tell you what to do, then your value-added is pretty low almost by definition. A centralization of power runs counter to the process of development. Finally, Xi’s approach to corruption has been purges, a focus on some vision of purer morality. If you think morality is the issue, then you’re not an economist. We think in terms of incentives. If a bureaucrat’s pay is $300 / month, and he can make another $1200 / month in kickbacks, he’s going to do that. His family’s budget depends on it. His wife needs that for the kids. So if you think moral purity is going to stop that guy from taking bribes, it really won’t. He’ll lay low until the purges pass (really, can China replace the 500,000 sanctioned bureaucrats?), and then it’s back to business as usual. To reduce corruption, you need to take a systems approach, in effect viewing bribery as a kind of business model. You have to change the model. I don’t see any sign Xi is interested in that at all.

In the absence of a visible and thoughtful commitment to reform, that leaves us with a really aggressive leader rapidly trying to monopolize power. That’s nothing more than a standard issue Asian despot. Right now, I think the data best supports such a thesis.

http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/meet-controversial-hong-kong-indie-871536

Some oil market data:

Tthe latest EIA data (released this week) indicate that US net crude oil imports are up by about a million bpd, year over year, up from 6.65 million bpd in early March, 2015 to 7.62 million bpd in early March, 2016 (four week running average data). Net crude oil imports as a percentage of US Crude + Condensate (C+C) refinery inputs rose from 43% last year to 48% currently.

And China crude oil imports hit record 8 million bpd in February:

http://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-china-economy-trade-crude-idUKKCN0WA0EP

Regarding India:

http://fuelfix.com/blog/2016/03/07/market-currents-eight-things-to-consider-about-the-oil-and-gas-market-today/

Some net export definitions:

Net exports = Total petroleum liquids + other liquids production less total liquids consumption (EIA)

Global Net Exports of oil (GNE) = Combined net exports from top 33 net exporters in 2005

Available Net Exports (ANE) = GNE less Chindia’s Net Imports (CNI, combined net imports by China + India)

Note that given an ongoing, and inevitable, decline in GNE, unless the Chindia regions cuts their net imports (CNI) at the same rate as, or at a faster rate than, the rate of decline in GNE, it’s a mathematical certainty that the rate of decline in the volume of GNE available to importers other than China & India (ANE, or GNE less CNI) will exceed the rate of decline in GNE and that the rate of decline in ANE will accelerate with time.

This is exactly what we observed from 2005 to 2013, to-wit, as GNE fell at 0.8%/year, ANE fell at 2.3%/year, because the rate of increase in Chindia’s Net Imports (CNI) exceeded the rate of decline in GNE, i.e., Chindia consumed an increasing share of a post-2005 declining volume of GNE (2014 data not yet available).