From a new book from Cambridge:

In this newly published volume, Yin-Wong Cheung

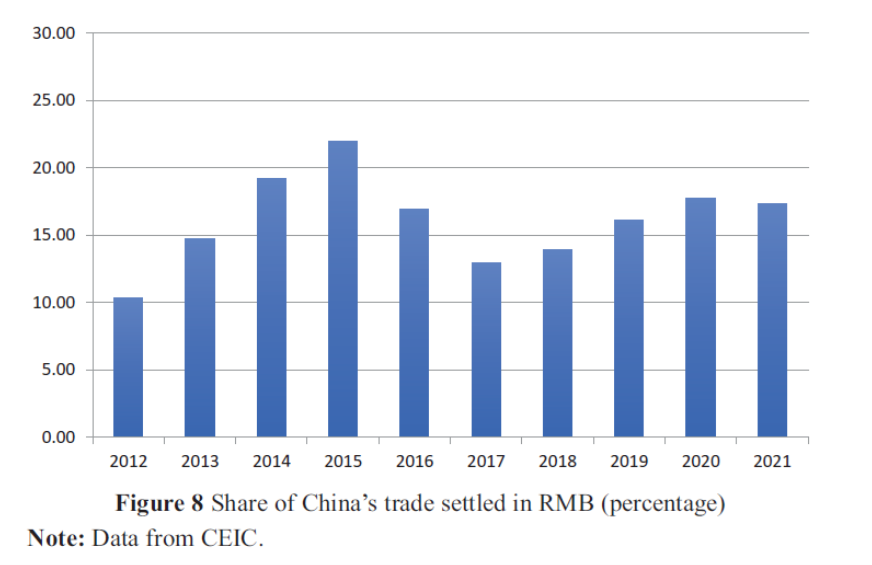

“discusses the global role of the RMB. After recapitulating its economic and trade growth experiences, we recount China’s evolving exchange rate policy in the post-reform era, review the debate over whether the RMB is overvalued or undervalued, present China’s policies to globalize the RMB, describe offshore RMB trading, assess the current global status of the RMB, and discuss geopolitical tensions in the last few years. Since 2009, the process of globalizing RMB has not been smooth sailing and has progressed quite unevenly over time. Despite the strong performance in the early 2010s, the RMB is underrepresented in the global market and its global role does not match China’s economic might. The path of RMB internationalization is affected by both China’s economic performance and

geopolitical factors.”

Regarding RMB internationalization, Cheung notes:

After reaching the 2015 high point, the process of globalizing the RMB has progressed quite unevenly and, in some areas, has even reversed. The change occurred in parallel with China’s heightened (administrative) foreign exchange management, financial deleveraging policies, and the concurrent increase in global uncertainty and geopolitical tensions that have decreased global demand for RMB-denominated assets. Further, the eruption of the China-US trade dispute and the subsequent change in the view toward China do not favor the international use of the RMB. The 2020 coronavirus pandemic presented China with another chance to regain the momentum of globalizing its currency. The pandemic impacted China hard in the first half of 2020; however, with its effective public health control measures, China demonstrated its economic resilience in late 2020 and 2021.32 This speedy economic recovery and the RMB’s stability have improved the attractiveness of RMB-denominated assets to international investors and enhanced the global usage of the RMB.

In the following subsections, we recount China’s main policies for promotion of RMB internationalization and discuss its outsourcing practice – the offshore RMB trading. China’s RMB internationalization program covers and interacts with a wide range of topics. While a complete coverage of RMB international-ization is beyond the scope of this study, we offer an overview.

Source: Cheung (2022).

Any scholar wishing to follow China’s policies regarding its exchange rate must read this volume.

My thoughts on previous essays on China’s currency include Eswar Prasad’s Gaining Currency (2015), Paulo Subacchi’s The People’s Money (2017). My take on the RMB’s status relative to the dollar was presented at a recent Board-NY Fed conference.

If the author’s name sounds familiar, he (along with myself and Eiji Fujii) coauthored The Economic Integration of Greater China (2007) (we’re working on an update now), several works on RMB misalignment (most recently, Cheung, Chinn and Xin, 2017), exchange rate prediction (most recently Cheung, Chinn, Garcia Pascual, Zhang, 2019), and on Chinese imports and exports (Cheung, Chinn, Qian, 2015).

Netting of FX positions is important in settlement of trade.

I’m not all that familiar with trade payment and finance, but it seems obvious that the amount of trade settled in a particular currency is not the whole story in that currency’s international role. By negotiating payment in yuan, Chinese firms may simply be inducing a second FX transaction to allow the other party to the trade to move from yuan to some target currency, such as euros, yen or dollars. The cost of that FX transaction is the an additional cost to the trade transaction.

One thing that matters is two-way trade. Netting covers everything but the imbalance. If the imbalance in trade between China and Vietnam, for instance, amounts to only 10% of Vietnam’s exports to China, the netting covers 90% of FX transactions (or something like that). It’s convenient to denominate trade in either yuan or dong if netting accounts for a large share of payment.

If, on the other hand, there is a large imbalance, then denominating trade in some other currency might make greater financial sense. So if China engages in a lot of unbalanced two-way trade, then it will be costly for trade partners to settle in yuan. Since the yuan is not much of a reserve currency and there aren’t lots of off-shore holdings of yuan-denominated assets relative to China’s overseas trade, holding yuan is risky and costly.

In other words, requiring settlement in yuan may raise the cost of doing business by imposing the cost of an FX transaction. So I kinda wonder if efforts to “internationalize” the yuan through a policy of trade settlement in yuan can work. Opening capital markets, creating a more extensive social safety net, allowing market-determined interest rates on saving all seem likely to internationalize the yuan more effectively than mandates. In other words, more market, less command.

Repeating –

During Saturday night’s protest in Shanghai – China’s biggest city and a global financial hub in the east of the country – people were heard openly shouting slogans such as “Xi Jinping, step down” and “Communist party, step down”.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-63771109

There are a couple of stories regarding the Communist Party’s hold on power in China. One is a story of legitimacy – paternalism is legitimate when the benefits of paternalism seem abundant, when people’s expectations are met. The other is a story of a monopoly on violence – surveillance, authoritarian rule, intolerance to diversity of thought. Both are true in some measure, because both are always true.

So what happens when the legitimacy story develops cracks? One thing that happens is that those in power rely more heavily on violence, threatened and real. Think of Tiananmen Square, of the crushing of Hong Kong’s efforts to hold on to promised liberty, of Kent State, of Iranians blinded by bird shot.

The Communist Party’s claim to legitimacy is badly tarnished right now – slowing economic growth, a real estate sector in tatters, a draconian Covid response that is less effective every day, a youth unemployment rate just off a record high and still trending upward. People are in the streets – as they were in Hong Kong and Tiananmen Square before being violently supressed by the government.

So I’m wondering what’s next for Chinese protestors and for the legitimacy of Party rule.

MD,

Maybe these demonstrators slept through the recent Party Congress. I mean, gosh, they should have been thiilled by the heightened prospect of a war toconquer Taiwan! Such a glorious prospect! I mean, look what invading Uiraine has done for the happiness of the people of Russia!

Nonsense.

For all its many faults, the CCP is the first dynasty in all of history to actually feed the people.

That goes a long ways toward addressing the threat of unrest so severe as to shake the grip of the Party.

Every family has first-hand stories of not having enough to eat, until recently.

Yes, there are disgruntled elements (as everywhere) who would happily tear it all down and start over.

As is common around the world, those elements haven’t a clue what it will take to overthrow the regime, haven’t the resources to undertake a long-term insurrection, haven’t the charismatic leadership to arouse the masses, and most certainly haven’t the majority — or even 25% — of the people behind them.

And, they don’t have the guns.

Not yet.

Maybe someday.

Probably someday, but not in my lifetime.

The “ a global financial hub in the east of the country” description needs to be shot down.

Count the number of foreign — as in “NOT Chinese” — companies listed on the Shanghai stock market.

Multiply by the number of international bond issues initiated by foreign — as in “NOT Chinese” — companies.

Divide by the yield curve, and the answer is … an even, natural number slightly south of one.

China’s international financial is Hong Kong; Shanghai’s wholly domestic.

I did not see any mention of this in the discussion of what is in the book, but last I checked it that the PRC continued to have exchange controls on its currency. It seems that in the post 1973 world of largely floating exchange rates among the major currencies that it is inconceibable that a nation could have its currency be a serious candidate to become the dominant global currency if the nation engages in such a policy. The US could get away with this in the decades immediately after WW II when its GDP was such a large proportion of that of the world and essentally all nations had such currency controls. But not anymore.

China’s cross-border currency controls are a joke.

Anyone who can’t get money in or out of China is either woefully inadequate for the job, or not really trying all that hard.