The ironies abound

As I’ve noted before, Senator Sanders has unique views on financial regulation. I’ve never quite understood the specifics of the “break up the banks” proposal, and after his interview with the New York Daily News and subsequent “clarification”, understood even less.

The Interview

Daily News: Okay. Well, let’s assume that you’re correct on that point. How do you go about doing it?

Sanders: How you go about doing it is having legislation passed, or giving the authority to the secretary of treasury to determine, under Dodd-Frank, that these banks are a danger to the economy over the problem of too-big-to-fail.

Daily News: But do you think that the Fed, now, has that authority?

Sanders: Well, I don’t know if the Fed has it. But I think the administration can have it.

Daily News: How? How does a President turn to JPMorgan Chase, or have the Treasury turn to any of those banks and say, “Now you must do X, Y and Z?”

Sanders: Well, you do have authority under the Dodd-Frank legislation to do that, make that determination.

Daily News: You do, just by Federal Reserve fiat, you do?

Sanders: Yeah. Well, I believe you do.

Daily News: So if you look forward, a year, maybe two years, right now you have…JPMorgan has 241,000 employees. About 20,000 of them in New York. $192 billion in net assets. What happens? What do you foresee? What is JPMorgan in year two of…

Sanders: What I foresee is a stronger national economy. And, in fact, a stronger economy in New York State, as well. What I foresee is a financial system which actually makes affordable loans to small and medium-size businesses. Does not live as an island onto themselves concerned about their own profits. And, in fact, creating incredibly complicated financial tools, which have led us into the worst economic recession in the modern history of the United States.

Daily News: I get that point. I’m just looking at the method because, actions have reactions, right? There are pluses and minuses. So, if you push here, you may get an unintended consequence that you don’t understand. So, what I’m asking is, how can we understand? If you look at JPMorgan just as an example, or you can do Citibank, or Bank of America. What would it be? What would that institution be? Would there be a consumer bank? Where would the investing go?

Sanders: I’m not running JPMorgan Chase or Citibank.

Daily News: No. But you’d be breaking it up.

Sanders: That’s right. And that is their decision as to what they want to do and how they want to reconfigure themselves. That’s not my decision. All I am saying is that I do not want to see this country be in a position where it was in 2008, where we have to bail them out. And, in addition, I oppose that kind of concentration of ownership entirely.

You’re asking a question, which is a fair question. But let me just take your question and take it to another issue. Alright? It would be fair for you to say, “Well, Bernie, you got on there that you are strongly concerned about climate change and that we have to transform our energy system away from fossil fuel. What happens to the people in the fossil fuel industry?”

That’s a fair question. But the other part of that is if we do not address that issue the planet we’re gonna leave your kids and your grandchildren may not be a particularly healthy or habitable one. So I can’t say, if you’re saying that we’re going to break up the banks, will it have a negative consequence on some people? I suspect that it will. Will it have a positive impact on the economy in general? Yes, I think it will.

Daily News: Well, it does depend on how you do it, I believe. And, I’m a little bit confused because just a few minutes ago you said the U.S. President would have authority to order…

Sanders: No, I did not say we would order. I did not say that we would order. The President is not a dictator.

Daily News: Okay. You would then leave it to JPMorgan Chase or the others to figure out how to break it, themselves up. I’m not quite…

Sanders: You would determine is that, if a bank is too big to fail, it is too big to exist. And then you have the secretary of treasury and some people who know a lot about this, making that determination. If the determination is that Goldman Sachs or JPMorgan Chase is too big to fail, yes, they will be broken up.

Daily News: Okay. You saw, I guess, what happened with Metropolitan Life. There was an attempt to bring them under the financial regulatory scheme, and the court said no. And what does that presage for your program?

Sanders: It’s something I have not studied, honestly, the legal implications of that.

…

Daily News: Okay. But do you have a sense that there is a particular statute or statutes that a prosecutor could have or should have invoked to bring indictments [against the banks for fraudulent activities]?

Sanders: I suspect that there are. Yes.

Daily News: You believe that? But do you know?

Sanders: I believe that that is the case. Do I have them in front of me, now, legal statutes? No, I don’t. But if I would…yeah, that’s what I believe, yes. When a company pays a $5 billion fine for doing something that’s illegal, yeah, I think we can bring charges against the executives.

Daily News: I’m only pressing because you’ve made it such a central part of your campaign. And I wanted to know what the mechanism would be to accomplish it.

….

Critique and Response

There has been substantial reportage on whether Senator Sanders knows the specifics of what he has in mind for breaking up the banks. Strangely, he seems to indicate that it’s not up to the regulators to determine the nature of the break-ups, rather it’s up the the entities themselves into what parts they’ll be cut up into. That’s only one of the oddities. The other is the dispute over whether new legislation is — or is not — required to effect the break up of the banks. Perhaps in response to the furor over Sanders’s apparent confusion (“pretty close to a disaster”, “How much does Bernie Sanders know…”, charitable view here), the Sanders campaign released this statement today:

“Within the first 100 days of his administration, Sen. Sanders will require the secretary of the Treasury Department to establish a “Too-Big-to Fail” list of commercial banks, shadow banks and insurance companies whose failure would pose a catastrophic risk to the United States economy without a taxpayer bailout.

“Within a year, the Sanders administration will work with the Federal Reserve and financial regulators to break these institutions up using the authority of Section 121 of the Dodd-Frank Act.

“Sen. Sanders will also fight to enact a 21st Century Glass-Steagall Act to clearly separate commercial banking, investment banking and insurance services. Secretary Clinton opposes this extremely important measure.

When I read this press release, then I became really confused.

Why Do We Need a President Sanders to Break Up the Banks?

It is interesting that Senator Sanders does not go into the details of Section 121. Section 121 is all about the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, exactly the entity that Bernie Sanders wants to audit. Here is the relevant text of Section 121 of the Dodd-Frank Act:

Dodd Frank Act Section 121

SEC. 121. MITIGATION OF RISKS TO FINANCIAL STABILITY.(a) MITIGATORY ACTIONS.—If the Board of Governors determines that a bank holding company with total consolidated assets of $50,000,000,000 or more, or a nonbank financial company supervised by the Board of Governors, poses a grave threat to the financial stability of the United States, the Board of Governors, upon an affirmative vote of not fewer than 2/3 of the voting members of the Council then serving, shall—

(1) limit the ability of the company to merge with, acquire, consolidate with, or otherwise become affiliated with another company;

(2) restrict the ability of the company to offer a financial product or products;

(3) require the company to terminate one or more activities;

(4) impose conditions on the manner in which the company conducts 1 or more activities; or

(5) if the Board of Governors determines that the actions described in paragraphs (1) through (4) are inadequate to mitigate a threat to the financial stability of the United States in its recommendation, require the company to sell or otherwise transfer assets or off-balance-sheet items to unaffiliated entities.

So, Senator Sanders plans to delegate to the Federal Reserve breaking up the banks? In that case, how does electing a President Sanders move foreward breaking up the banks if existing authority already allows the Fed to break up the banks. Or, does President Sanders intend to re-write the Federal Reserve Act so that he can direct the Fed to take specific actions at the President’s behest? That seems to be the logical implication.

The irony is that the Fed is exactly the entity that has been the focus of so much of the Senator’s ire, so much so that he joined Rand Paul in voting to Audit the Fed!!!!

Does Breaking Up the Banks Even Make Sense?

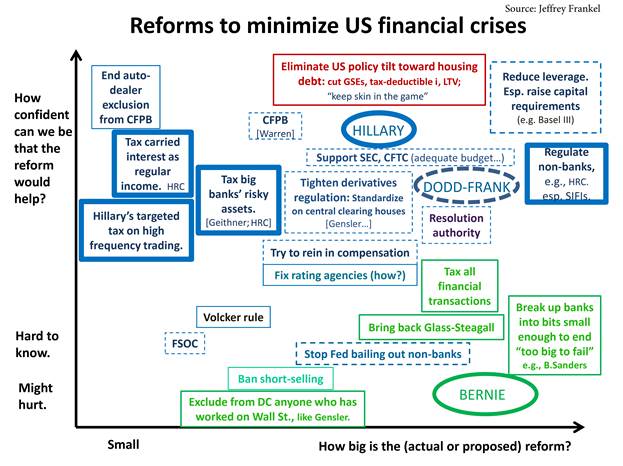

As various observers have noted, it is unclear that breaking up the big banks would make the US financial system more stable. Jeffrey Frankel has drawn up a diagram that shows what policies would actually help.

Source: Jeffrey Frankel.

In other words, most of the policies proposed by Senator Sanders would be largely diversions, rather than dealing with the problem of financial instability.

Update, 4/8, 7PM Pacific: For additional discussion of some of the complexities, see this article.

Neel Kashkari, President of the Minneapolis Fed who oversaw TARP for Paulson, wants to break up the banks.

Sanders could as his friend Elizabeth Warren for her input.

Dean Baker disagrees with you here:

http://cepr.net/blogs/beat-the-press/reporters-who-haven-t-noticed-that-paul-ryan-has-called-for-eliminating-most-of-federal-government-go-nuts-over-bernie-sanders-lack-of-specifics

Mike Konczal here:

http://rooseveltinstitute.org/sanders-ending-tbtf/

Just seems like the Clinton campaign is on the attack after a string of Sanders victories and going into New York. Unpleasant to witness.

Sanders also has a financial transaction tax which is used to fund his free public college policy. Clinton does not which is not surprising given how much Golden Sachs has paid her for her wonderful speeches. Wall Street doesn’t just hand out free money. They want something in return.

Peter K.: Yes, I know Mr. Kashkari wants to break up the banks. By the way, Kashkari oversaw TARP under both Paulson and Geithner.

I agree with Dean Baker that Representative Ryan’s plans have not received sufficient attention regarding lack of details. That’s why I have excoriated Representative Ryan’s plans on many occasions — just check. I think we need to critique all plans.

Finally, regarding the financial transactions tax. Economists have debated such a tax (the “Tobin tax” for the unitiated) for a long time. Can you imagine that some people might oppose for reasons aside from pure avarice/influence peddling? Think about the implications of imposing a financial transactions; what happens if the US does, and the rest-of-the-world doesn’t. International economists have. Maybe a President Sanders could wave a wand and get an international treaty to do so. I won’t hold my breath.

Maybe I’m misinformed but Wikipedia has a long list of countries that already have a financial transaction tax.

“In 2011 there were 40 countries that made use of FTT.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Financial_transaction_tax

There already has been a financial transaction tax proposal for the EU but they are dragging their feet on implementing it.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/European_Union_financial_transaction_tax

Spasen V: Sure, there are select financial transactions taxes. You should read in the article you cite how comprehensive they are (breadth of coverage), and how many are viewed as failures due to circumvention.

In the EU, if I read it correctly, they still need formal approval in order to move forward.

By the way, I think a financial transactions tax of small amount would be a good idea, particularly if conjoined with an international agreement. I just don’t think it would raise as much revenue as many think.

‘Economists have debated such a tax (the “Tobin tax” for the unitiated) for a long time. …what happens if the U.S. does and the rest of the world doesn’t. International economists have.’

As you know such a tax has already been proposed by the European Union in 2014. Predictably some member countries worry that their economies will be hurt. So the issue of coordination with other governments/countries would not appear to be as big as you seem to imply.

More broadly though, you know that the ftt is a completely different question from tbtf. Why does Sanders mention it then? Probably because it would lead to a reduction in the amount of financial churning.

Clearly Sanders think the bigger problem is political; a need to generate and/or focus political will.

William Osterberg: I think that Senator Sanders is proposing a financial transactions tax because (1) it has populist appeal, and (2) he needs revenue.

I thought Franke’s recent piece on inequality was very slanted against Sanders and biased in favor of Clinton. Not fair or objective.

http://www.jeffrey-frankel.com/2016/03/25/inequality-diagnoses-and-prescriptions/

You yanks will have it tough if you have to choose between this bloke and Trump. Which nut-case is worse

???

Perhaps it would be simpler to provide absolute requirements for government backing and have the FDIC withdraw account insurance from banks that do not adhere to the requirements. Individuals can then decide where they want to put their money. The government gets out of the bailout business and the marketplace decides how much risk it will accept. Let the DOJ watchdogs be on the lookout for fraud. Set up a tip line. Penalties are jail, not fines.

Non-regulated/uninsured lenders are on their own. Gamblers are welcome to play in the unregulated or poorly regulated sandbox, but at their own risk… not everyone else’s. Give the SEC power to focus on gimmicks like derivatives. http://www.reuters.com/article/usa-funds-regulations-idUSL1N1401IW20151211

It’s not size that matters; it’s performance that matters.

One area I’d like to see more research on is whether the “Lehman Moment” was actually a thing. A lot of discussion assumes that TBTF reflects true risk as opposed to the perception of risk. But there are other theories like how the “Lehman Moment” was mostly significant due to monetary, and/or fical, policy signaling. Those perspectives look at things like daily equity movements to throw some shade at the systematic significance of Lehman. If there is some truth to the signaling theory, or alternative theories that lessen the importance of big institutions, then future regulators can take much more aggressive stances.

the lehman moment was real. institutions of that size do not simply go bankrupt due to hypothetical situations. it also demonstrated the enormous integration of financial risk the large institutions had created. TBTF is not simply about how large an entity is, but also its influence on other institutions. under the scenario that unfolded, it is really difficult to discount the importance of TBTF in the outcomes we observed. if you allow leverage into the system, you develop integrated systems where TBTF becomes a big problem. this is why increased collateral backing is being pushed in the reform programs.

I hear you, and to be clear, it seems obvious that Lehman’s failure represented a contractionary event. But the “Lehman Moment” implies a near inevitable tip into the Great Recession. Is that true? There is a suspicious gap between the intuitiveness of the Lehman Moment, and the ability to prove it through the data. For example, some financial stress measures, like the TED and LIBOR-OIS spreads, show a quick uptick in the week after September 15, followed by a few days of rapidly diminishing stress, and another huge uptick. What happened in those few days of ease? Is that just noise, or was the market anticipating something that could have prevented further collapse? In the latter case, what we ascribe to Lehman’s collapse includes the procyclical effects of whatever didn’t happen that the market might have anticipated. I don’t know, but it’s a question that has some important policy implications, and yet it doesn’t receive much attention.

Also note the relatively benign stock market reaction in the few days after Lehman’s collapse. Delayed reaction, or expectations unmet? Without assuming too much about market efficiency, it’s still interesting to go back and question how much of Lehman’s impact includes specific policy responses.

Another hit piece against Sanders. This grows tiresome.

Permit me to suggest a failure of high-order reasoning here. Most of Hillary’s proposals are not possible without breaking up the too-big-to-fail banks because banks of such large such tend to capture both congress and the regulatory agencies, blocking reform.

More to the point, these continues hits against Sanders obscure the real problem: most of the systemic risk in the world financial system right now appears to reside in the shadow banking sector, and neither Hillary nor Sanders have suggested mechanisms for regulating the shadow banking sector.

Chinn will predictably retort that Hillary’s suggestions “tax big banks’ risky assets” and “tighten derivatives regulation” and “regulate non-banks” constitute regulation of the shadow banking sector — but the problem is that current regulators do not even known the assets held by non-banking entities, nor are they aware of the risks of such assets. And for good reason — the non-banking entities themselves typically do not know, and have no easy way of finding out, the risks of such assets. So what Hillary is proposing is mere magic-wand-waving. She wants to sprinkle the magic fairy dust of “tax big banks’ risky assets,” but how to we find out which assets are risky so that we can tax them, and how do we find out how risky they are so we know how much to tax them? With a magic pony? By clicking our ruby slippers together 3 times? How do we “regulate non-banks” without knowing which assets are risky? By shaking our witch doctor rattles and intoning some magic ju-ju?

Source: “The Ten Reasons Why There Will Be Another Systemic Financial Crisis,” Robert Lenzner, 8 December 2014.

As a prebuttal to Menzie Chinn’s predictable response that we can find out exactly how risky the Margan Stanley and Goldman Sachs et al. assets are by forcing them to disgorge their confidential internal data, the evidence shows that these giant institutions had no idea in 2006-2007 how risky their assets were. Even the TBTF banks didn’t know their risks prior to the crash of 2009! And this is why I’m more inclined to trust Larry Summers and Martin Wolf on this issue than Menzie Chinn.

We now return the reader to the regularly schedule hagiography of Hillary Clinton’s long-debunked and largely useless economic proposals.

If this is your idea of a hit piece, then you should take a break from any political discussions. Your brain is melting under histrionic self-righteousness.

‘Most of Hillary’s proposals are not possible without breaking up the too-big-to-fail banks because banks of such large such tend to capture both congress and the regulatory agencies, blocking reform.’

To anyone who is familiar with the history of American banking law that is hilarious. It was the ‘unit banks’, small, undercapitalized, mostly rural that captured politicians in congress and state legislatures. They prevented branch banking, often even within states, and prevented interstate banks from forming. Which is why the American system was prone to bank failures. Unlike Canada which had five large nationwide banks, and never had a problem with bank failures.

And, of course, Sanders is also wrong about ‘Glass-Steagall’. It was never repealed. The separation of investment and commercial banking was under sections 16 and 21 of the Banking Reform Act of 1933, and still is the law. So is the FDIC–walk into any bank lobby and verify that for yourself.

Breaking-up large banks would not reduce systemic risk from government policies.

I think, Sanders wants to punish large banks, because they became so successful.

mclaren:

Question 1: Is a “hit piece” by definition in your Weltanschauung anything that is critical? I get that distinct impression. Please tell me anything that is factually incorrect. Where we disagree, I think reasonable people could similarly disagree, without one side being “shills”, as defined in your terminology.

Question 2: If your model of “capture” is so deterministic, then why did Dodd-Frank ever pass? In my view, “capture” doesn’t explain everything; see Chinn and Navarro (1984).

Question 3: Regarding the shadow banking system, the Dodd-Frank legislation regulates banks and nonbanks. I would say that what more is needed in that regard, save in the repo market. Do you have a specific concern?

Question 4: Regarding risky assets — the problem in 2008 was not so much ignorance about the assets the balance sheet, as the risk attributes of the assets. Basel III restricts much more tightly risk-weighting, including for derivatives.

You are of course free to choose whom you believe. Larry Summers and Martin Wolf are both people I respect, but, again, reasonable people can disagree, without one or the other being a “shill”.

If you want to see a more extensive exposition of my views, see Lost Decades, published in 2011.

I will admit that it is disappointing that Sanders did not have more details available for the NYDN interview. On the other hand, I agree with his overall focus on the huge problem of money in politics. As long as Goldman, JP Morgan, et.al can bombard Washington with lobbyists and even end up in the Treasury Dept. etc. where they help implement financial regulatory policies then the details (figuring out in advance what the implications of alternate methods would be, exactly what constitute too big too systemically important, etc.) are of secondary order importance, IMO.

Is it that odd that he says the banks will decide into what pieces they will be broken up? I agree that there will be some limitations on what form they can take but

then they will self-organize given those limitations. If he makes the mistake of going into specifics then he runs the risk of letting voters think that this is a technical problem: we know that there are many (including professional economists [I am one]) that will elaborate on these.

What exactly is inconsistent about wanting scrutinize the Fed (‘audit’) and giving it overall authority in ‘breaking up the banks’?

Frankel’s diagram on what policies would help, etc. seems pretty subjective. e.g. So assuring funding for the SEC and CFTC would make a relatively big difference even if they are hiring people from GS et.al.?

Having watched DF being hashed out by a divided Congress alongside financial sector lobbyists I am all for emphasizing political change first and working out the details later.

While there have been several examples of failure to raise revenues, there have also been notable successes. For example, Taiwan and Hong Kong raise roughly 1%-2% of GDP per year using the FTT. So it is not outside the realm of experience to generate large sums with an FTT, and they only have one on equities and not bonds/derivatives. Source Table 2 in Matheson 2011: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2011/wp1154.pdf

Moreover, it bears mentioning that tax rates such as 50 bps on equities, 10 bps on bonds, and .5 bps on the underlying values of equities are well within historical ranges of transactions costs which naturally occur in markets, so in all likelihood taxes in this range will probably not break the market.

Finally, I think it is interesting that the financial industry has consistently claimed that taxes in this range will break the market; however they have never made this claim in regards to their own commissions, which are functionally the same thing because they also increase transactions costs.

I don’t think there can be any serious doubt that Clinton is way wonkier than Sanders will ever be. She knows issues inside out and upside down. Sanders does not have much in the way of technical knowledge. He just doesn’t. The good news for Sanders is that this is a correctable problem. A President Sanders would have an army of lawyers and economists at his disposal to advise him and draft legislation. We saw something similar play out during the 2008 election. Sen. Obama was way behind the power curve on healthcare and foreign policy. Clinton could talk circles around Obama on just about any issue. But Obama was able to pass healthcare reform and Clinton wasn’t, with the added irony that Obamacare ultimately looked a lot more like Hillarycare than what candidate Obama was advocating. Obama learned that a President can buy knowledge and technical expertise. What a President cannot buy is political trust, and that gets to the core of Clinton’s problem with many Democrats. I like Clinton and I hope she wins, but with Clinton there’s always this gnawing suspicion that come 12:01 PM on 20 Jan 2017 her first priority will be to plan her 2020 re-election, which will likely require big donations from Big Pharma and the TBTF banks. That gnawing suspicion might be misplaced…I hope so…but Bill Clinton’s “Third Way 2.0” isn’t very inspiring. On the policy issues I’m in very close agreement with Clinton, I’m just not sure about her commitment to do what she knows is the right thing. Another often overlooked concern with Clinton is her exceptionally clumsy executive skillset, which is likely not unrelated to her wonkiness and tendency to want to micro-manage. Her 2008 campaign was badly managed and her 2016 campaign isn’t a lot better. She should be walking away with the nomination, leaving Bernie in the dust. But she’s struggling. This says something about her executive skills and ability to delegate responsibilities to talented people. And if you talk to senior career types at Foggy Bottom they will tell you that the way she ran State could only be described as bungling. It’s not that she didn’t understand the issues; the problem was that she didn’t understand her own bureaucracy. That’s a problem if you’re President. Being President is not the same thing as being Head Wonk. I have no idea if Sanders’ executive skill set is any better than Clinton’s, but I do think his instincts are better. And at 12:01 PM on 20 Jan 2017 he won’t be thinking about his re-election in 2020. That’s both a good thing and a bad thing.

Maybe we should amend the Constitution to allow Obama to run for a third term.

Hi Menzie,

Won’t Bernie argue that he will use his Presidential authority to convince the FED that action should be taken? And could not his issue with the FED have to do with his conviction that the FED should break up the banks?

William Anderson: The President could try to persuade the Fed to break up the banks, under the authority granted by Section 121 of the Dodd-Frank legislation. The Fed is an independent agency, under its charter. Trying to “persuade” the Fed is probably an unhelpful action, to the extent that it subjects the Fed to political pressures. If conservatives were to argue that the Fed should be “persuaded” by the executive branch to strictly target inflation (ignoring unemployment), I think there would be (rightly) an uproar. There is, after all, a reason in advanced economies and emerging market economies, there has been a move toward central bank independence.

However, I do believe that Senator Sanders’ attempt to “persuade” the Fed is in consistent with his support for the “Audit the Fed” legislation to the extent that both would represent an attempt to reduce Federal Reserve system autonomy.