Today, we are fortunate to present a guest contribution written by Ashoka Mody, Charles and Marie Visiting Professor in International Economic Policy, Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University. Previously, he was Deputy Director in the International Monetary Fund’s Research and European Departments. He is the author of “EuroTragedy: A Drama in Nine Acts,” recently updated with a new afterword.

On February 28, I wrote a piece with a premonition: “Italy: the crisis that could go viral.” With events moving so quickly, on March 10, I did a follow-up with a more urgent message: “Italy will need a precautionary bailout—a financial firewall—as the coronavirus pushes it to the brink.” A lifetime has passed since then. I had feared things might go badly but had no special insight into the extraordinary speed at which the virus would multiply and the economic damage it would inflict. But I think the framework that guided the economic and financial analysis of those earlier pieces was, and is, a useful way of thinking how this crisis will unfold. These are its four building blocks:

- This is the first crisis since the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1920 to begin as an economic rather than financial crisis. Unlike at the time of the influenza pandemic, the coronavirus crisis is occurring in a much more globalized economy. Beginning with China, the virus has—and will keep—disabled some of the nerve centers of global trade.

- Contemporaneous stock market declines result in enormous wealth loss, but by themselves, do not cause systemic financial crises. Instead, the true financial vulnerabilities are in the credit markets, and those are just emerging onto center stage. A financial crisis was likely even without the corona crisis. Since 2010, a classic debt bubble had built up: borrowers around the world, enticed by low interest rates, had pumped up their debt ratios, a prelude to every financial crisis that historians have recorded. The coronavirus shock is bursting that bubble. The longer the ongoing stress continues, the more severe the eventual debt crises will be.

- Policy authorities have understood the principle that early action helps prevents an economic and financial crises from snowballing. And while politics gets in the way of implementing this principle, central banks and governments have, in general, responded quickly. The question is, and will remain, one of relative speed. Will the crisis run ahead of the policy response?

- Europe is particularly vulnerable because European nations depend heavily on trade and they have, with some differences across countries, built up extremely large debt ratios. Their banks are not only huge but also extremely weak, judging by market metrics. Within Europe, Italy is especially vulnerable economically, financially, and politically. As Europeans face an existential challenge to their postwar cooperative enterprise, the biggest question mark will be on how they deal with the forces that will pull them apart.

The economic crisis is centered on global trade nodes

The economists Robert Barro, Jose Ursua, and Joanna Weng report that over its three-year course, the Great Influenza Pandemic caused GDP and consumption to decline by 6% and 8%, respectively, in a “typical” country. The domestic manifestations of that pandemic were similar to the current one. Hardest hit were small, community-based businesses, whose sales fell by between 40 and 70 percent; industrial plants, coal mines, and even utilities suffered from shortage of manpower. Railway transportation was “curtailed.”

The coronavirus crisis, has the potential to be much deeper because it has disabled global trade. Of crucial importance, the new virus originated in China—the global economic locomotive since the turn of this century. The Chinese economy had been slowing since the start of 2018 and, with that slowdown, its imports and exports had decelerated even before the tariff war between China and the United States began. These prior factors had already caused international trade to contract in the final months of 2019. Once the coronavirus began to spread and Chinese authorities started limiting the movement of workers and shutting down factories, Chinese trade collapsed, causing extraordinary additional damage to international trade.

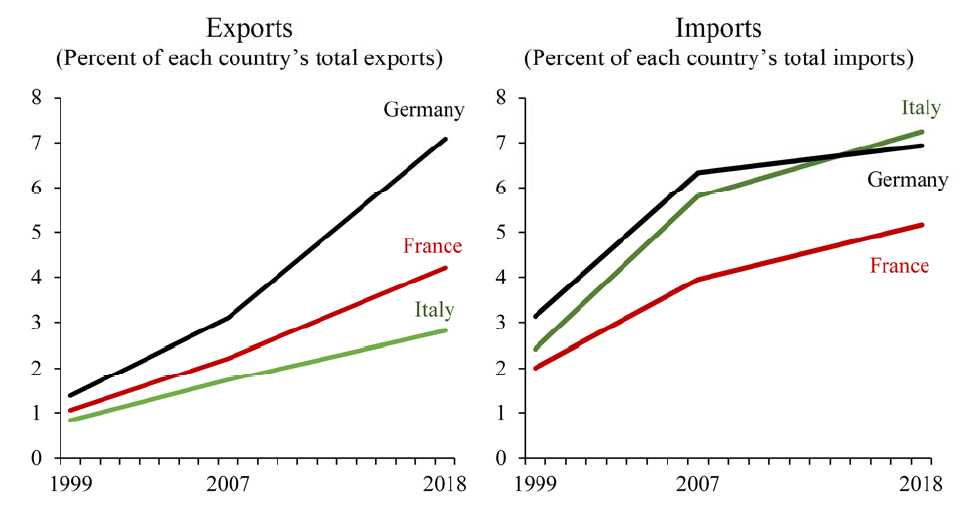

In addition, over the last two decades, trade links had deepened between China and the eurozone, whose member states form some of the other major world-trade nodes. There is some irony in the more intense China-eurozone trade, since the stated purpose of the euro was that it would strengthen trade ties among euro members. But the latest econometric study confirms that eurozone nations did not step up trade with each other. Instead, European trade grew rapidly in the 1990s and 2000s, with non-eurozone countries, especially with the booming China, making Europeans ever-more dependent on the performance of the Chinese economy.

Figure 1: Europe’s increasing trade dependence on China. Source: IMF Data, http://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61013712.

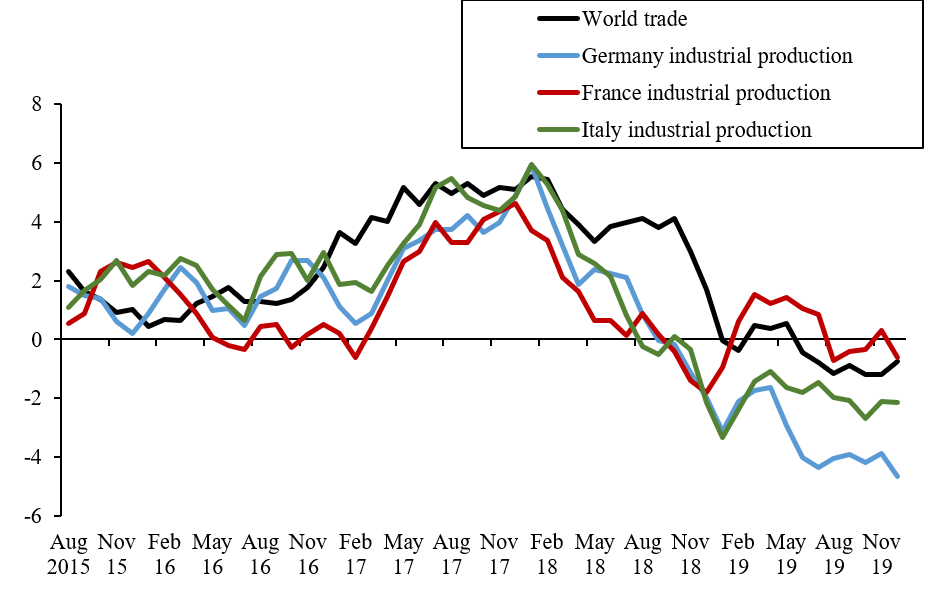

Hence, in the last two decades, whenever the Chinese economy slowed, so did the European economies. That link was plainly evident during the 2018-2019 slowdown. While specific features of individual European countries did weigh on their ability to grow—Germany, for example, experienced a wrenching decline of its combustion-engine-based car industry—all European nations began slowing once the China-induced global trade deceleration began in early 2018.

Figure 2: By late last year, falling world trade had pulled Europe into near recession. (Annual growth rate, percent)

When China slows down, European countries are hit twice. Their direct trade with China shrinks; in addition, the knock-on effect of slower growth causes them to import less from each other. This China factor weighed heavily in my initial assessment of the likely severity of an economic crisis in Italy. That shock, I argued, could cause deep damage to Italy, in the same way a disease attacks the feeble most ferociously. Italy has not grown since it joined the eurozone in 1999, it has been mired in near-perpetual recession since 2010, and it was in another recession when the coronavirus crisis struck.

The reason the global economic crisis will likely continue for months is that a number of trade nodes that connect the network will remain impaired. China itself appears to have contained new infections and deaths. And reports suggest that some Chinese factories have resumed operation (semiconductor factories had apparently never shut down). Reports also suggest that Chinese authorities are trying to push out goods that have been waiting in the country’s ports. However, increased activity is not yet evident in financial markets. For example, in the spring of 2009, when the Chinese economy revved up, the Australian dollar, tied to the buoyant demand for Australian commodities, appreciated visibly. In this cycle, the Australian dollar is still testing the lows.

Moreover, even when China resumes something close to normal production, other countries must be ready to buy and sell. If, as now appears, the crisis will persist longer in Europe, China’s ability to pump up global growth will remain constrained. Meanwhile, emerging markets—Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Turkey—are also financially stressed as foreign capital is fleeing to the relative safety of U.S. dollar assets. For these reasons, restoration of the global trade network and, hence, the global economic recovery will take time. The prospect of a bounce back in the third quarter of this year, as many forecasters had hoped—and continue to hope—seems unrealistic at this point.

Credit markets begin to take note

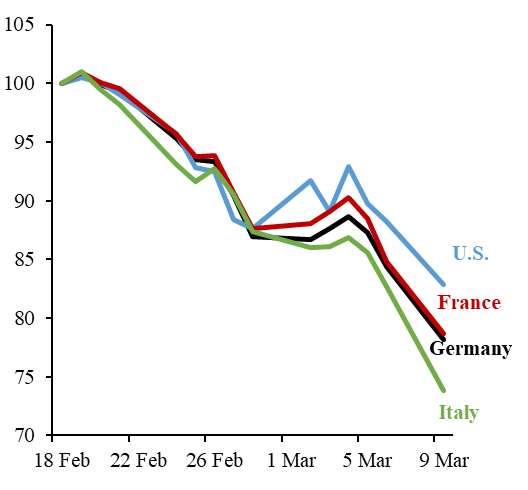

Not surprisingly, the first impact of the economic crisis was on stock markets, which began reevaluating economic growth prospects. In that initial assessment, stock markets recognized that Italy would be hardest hit.

Figure 3: Stock markets took a bleak view of Italian economic prospects (February 18, 2020 = 100)

Even though stock indices were in free fall, there was yet no financial crisis in the first two weeks of March. For perspective, in September 1998, stock markets took a gut punch when Long-Term Capital Management wobbled. But a U.S. Fed-orchestrated recapitalization of LTCM steadied the markets. Similarly, stock markets fell sharply when the tech bubble burst in the spring of 2000. The lesson is that unless investors have leveraged themselves heavily—borrowed large amounts of money—to buy stocks, a stock market crash does not typically lead to widespread financial distress.

More to the point, risk lurked in the global credit bubble that had built to a dangerous peak. According to the Washington-based Institute of International Finance, the global debt outstanding had doubled from $120 billion in 2006 to $240 billion in 2019, at which point it was 320 percent of world GDP. Virtually every country and every type of borrower took advantage of the low interest rates, especially over the last decade, to gorge on debt. Debt ratios rose especially for corporates and governments, and while the ratios for banks in advanced economies declined from dizzying heights, they remained higher than those for other types of borrowers.

In the second week of March, once it became clearer that the coronavirus would cause a deep and, possibly, extended economic slowdown, credit markets began showing signs of stress. The stress levels then were, and as yet are, relatively modest compared to the levels observed during the most intense phase of the global financial crisis between July 2007 and May 2009. Remember though that in that crisis, financial tensions rolled in waves across various credit markets, starting with the asset-backed commercial paper market. Quickly, the inter-bank market began to ration out borrowers and European banks experienced acute shortage of dollars. Soon enough—as the epicenter of the crisis shifted to the eurozone—the cost of credit to companies, banks, and governments rose sharply.

There is much reason to worry that the already visible credit market tensions will increase and spread in the coming weeks and months. As a general principle, financial crises are severe not just when outstanding debt burdens are high but when growth slows down rapidly, making it hard to repay that debt. Today, with a sharp decline in output and debt burdens high everywhere, a question mark hangs over the ability of borrowers to repay the mountain of debt. That question mark will grow larger, the deeper the economic crisis is and the longer it continues.

Policymakers have responded energetically

The Fed set the ball rolling by rapidly lowering interest rates (by reducing its policy rate and renewing bond purchases). The Fed has also injected considerable liquidity into the U.S. banking system and made dollar liquidity available on a large scale to several central banks. In its boldest move yet, the Fed has promised to buy U.S. government debt in unlimited amounts, while further backstopping other credit markets. The Bank of England has taken actions to lower rates and provide liquidity. The European Central Bank (ECB) has not reduced its policy rate but has expanded its bond purchases to about a trillion euros for the rest of this year and has added considerable liquidity into eurozone banks.

These are important actions, but they are suited to a conventional financial crisis not to the current problems. As long as people’s spending is constrained by the physical limits on their movements and by the shutdown of factories and services to contain the virus, lower interest rates cannot help. Liquidity into banks will surely support ongoing operations, but will not spur new activity.

Fiscal measures, properly targeted, could be more effective. On March 20, the British Chancellor of the Exchequer set the benchmark with a bold promise: “Government grants will cover 80% of the salary of retained workers up to a total of £2,500 a month.” He promised unlimited interest free loans for 12 months to small businesses, as well as tax cuts and cash grants. Such economic life support is crucial to sustain those who are losing their livelihoods and need to pay for food, utilities, and mortgages. Other targeted help—such as more generous family leave—will also provide a critical safety net. In a second phase, once the worst of the virus contagion is behind us but when financial stress, even a debt default crisis, is still with us, a more generalized spending stimulus will help boost the economy through spending multipliers and by instilling greater optimism.

But there is an immediate task at hand. Borrowers will soon begin defaulting on their loans, creating a new set of challenges for policymakers. The question, at its core, will be: how will the losses due to the defaults be distributed? Will debt be written down, or will debtors be allowed to repay debt over longer periods of time?

Why Europe is so vulnerable

More so than elsewhere in the world, major European economies ended 2019 and entered 2020 in a very weak economic condition. Since then the coronavirus has hit their domestic economies hard. And because they are so enmeshed in global trading relationships, their distress has been acute and will likely continue for some months, at least.

European financial vulnerabilities are also severe. Government debt-to-GDP ratios in the major eurozone nations—other than Germany—are near historical highs. European banks are fragile. While the banks’ non-performing loans (loans not being repaid on time) are down, their profitability is low. The market-to-book value (MBV) ratios of major European banks were below 1 before the coronavirus became so fearsome. Essentially, markets were saying that because of poor medium-term growth prospects in Europe, the banks are unlikely to get full value for the assets on their books. The market’s assessment has turned even bleaker with the spread of the coronavirus. The MBV ratios have fallen sharply. Germany’s Commerzbank and Deutsche Bank are particularly weak, with MBV ratios of around 20 percent. And matters seem set to get worse. Deutsche Bank has warned investors that it will be “materially adversely affected” by the prolonged downturn.

Each of the European weaknesses is particularly acute in Italy: prior economic infirmity, size of the coronavirus economic shock, government debt burden, and fragility of the domestic banking system. The Italian government owes about €2.3 trillion, about 135 percent of GDP. Italian banks have assets with a paper worth of about €5 trillion. But the true worth of the banks’ assets is likely much lower and will fall further as the economy struggles in the coming quarters. Italy’s Monte de Paschi bank has non-performing loans of about 17 percent of its assets. Even the strongest banks—UniCredit and Intesa Sanpaolo—have MBV ratios significantly below 1.

Treacherous moments—and terrible choices—lie ahead for Europe

In a reasonable scenario, a severe global economic crisis will continue and a financial crisis will intensify. Europe will feel the brunt of the twin economic and financial crises. The Italian government will move steadily to the edge of default; Italian banks will see a rapid accumulation of non-performing loans.

Eurozone governments do not have the fiscal resources to support a prolonged crisis. Even Germany is on shaky ground. The German government is embarked on borrowing about €350 billion, approximately 10 percent of German GDP, to prevent a domestic economic freefall. Fiscal resources to recapitalize the country’s banks may soon impose sizeable additional demands on the German government. The French and Spanish governments, each with debt ratios of around 100 percent of GDP, have even tighter fiscal limits. Possibly, Germany and, maybe France, could increase their budget deficits to 15-20 percent of GDP before credit markets and rating agencies take fright. But will the Germans have the fiscal space and political willingness to aid those unable to spend their way out of this crisis?

A discussion is now ongoing about the possibility of a precautionary credit line for Italy, along the lines I suggested two weeks ago. Anchoring such a credit line would be the eurozone’s bailout fund, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). I had proposed a credit line of between €500 and €700 billion, but the ESM has a lending capacity of only €410 billion. My proposal, therefore, included not only the International Monetary Fund but also, potentially the United States, perhaps, in a back-up mode. With time running so fast, the size of the bailout requirement has probably grown, making the proposed international political coalition even less likely. And what if Spain also needs similar support soon?

For now, eurozone policymakers seem to be relying entirely on the ECB to save the day. But it is not the central bank’s role to deal with insolvencies. In principle, the ECB can buy the Italian government’s debt to prevent a default. But the ECB is not a normal central bank; it is the central banker to a confederation of nations, each of which maintains fiscal sovereignty. If Italy is pushed to the brink, the ECB will struggle—technically and politically—to help.

Here’s why. The current ECB bond-buying limit of a trillion euros is designated to purchase the bonds of all member states. Italian government debt is over two trillion euros, and the Italian government’s debt will increase further if it is forced to financially prop up the country’s banks. If Italy has to be bailed out, other member states represented on the ECB’s Governing Council will face the choice of buying so much Italian debt that, in effect, the ECB would own Italy. What if the Italian government is unable to service its debt to the ECB? Other member states will end up with the politically charged task of using their tax revenues to replenish the ECB’s capital.

The alternative of leaving Italy to fend for itself could lead to widespread Italian defaults, triggering defaults by those who have lent to the Italian government and banks. A cascade of defaults would go up the chain to European and global pension and insurance funds, setting off a global financial panic.

At this moment of global crisis, the test is going to be whether each nation takes care only of itself or whether the strong help the weak. But will the strong remain strong long enough?

[Update 4/4/2020: https://briefingsforbritain.co.uk/charting-this-crisis/]

This post written by Ashoka Mody.

I’m still digesting Ashoka’s post before I comment. If you like classical piano music this might be a nice “escape” if you are in self-quarantine. It will be at 8:00am on Friday the 27th. She’s really talented:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NOjLcrmiXpw

I seem to remember Ashoka’s son plays violin, so maybe he will like it also.

Here’s my question: Let’s say Italy in essence goes into default, and Spain also, Or say Italy goes into default and Spain needs a large bailout “from the ECB”. Does this make Britain more happy or less happy they did Brexit?? I’m especially curious what 2slugbaits thinks about that. Looking at COVID-19 now, do you think Britain would like the ECB “having its back” or the Bank of England covering Britain’s back, without being on the hook for Italy….Spain….. France…… etc???

How does Brexit play out now, as far as, was it a good choice for Britain?? Here were my personal thoughts on the matter back in late March 2019, near EXACTLY one year ago, before Brexit was enacted:

https://econbrowser.com/archives/2019/03/uk-gross-fixed-capital-formation#comment-222781

Here is a scenario on Brexit I was sent by a very wise and cerebral PhD economist located in some university town in Wisconsin (a man I have a great deal of respect for). At the time, that gentleman and astute scholar (no sarcasm here) told me this scenario for Brexit was a “reasonable/mainstream view”.

https://www.parliament.uk/documents/commons-committees/Exiting-the-European-Union/17-19/Cross-Whitehall-briefing/EU-Exit-Analysis-Cross-Whitehall-Briefing.pdf

Look at the most extreme numbers (i.e. the ones everyone loved quoting at the time) and tell me how that looks now???. I’m honestly asking here—this is not purely a rhetorical question. It is asked in earnest to whoever deems it worthy to answer.

Moses Herzog I don’t understand your question. The UK was never part of the EZ, so what the ECB does or doesn’t do is largely irrelevant from Britain’s perspective. Britain’s monetary policy was always controlled by the Bank of England, not the ECB.

Currently the UK is in a kind of limbo status with regard to Brexit. This pandemic hit at a bad time…not that there was ever a good time. But that limbo status will probably make it harder for Britain because there will be just that much more uncertainty. Also, Brexit would have unambiguously hurt Britain’s healthcare system.

And now Boris Johnson has tested positive (as has Prince Charles), although apparently only a mild case, at least so far.

@ 2slugbaits

So you’re telling me as a member of the EU, Britain would not have any money (as in billions) parked at the ECB, or be on the hook for taking part in any bailouts made by the ECB?? Is that what you’re telling me?? Those decisions made by the ECB to bailout Italy and Spain effect the amount of money Britain “throws to the wind” if they have money parked with the ECB or have agreements where they have to participate in the bailouts as a member of the EU. If that is not part of the conditions of EU membership, I would be near shocked. Are you going to tell me that Sir??

Last time I checked America has been part of many European bailouts (being the creditor in nearly all cases), and America was “never part of the EZ”. So, again I ask good Sir, are you telling me Britain has no money parked at ECB or conditions to participate in bailouts of European nations as a member of the EU, pre-Brexit??

Moses Herzog You’ve lost me. I have no idea what you’re talking about.

@ 2slugbaits

Something tells me most British taxpayers might have a clue and a memory of what I am talking about.

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/uk-gives-42bn-to-portugal-bailout-2285276.html

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/banksandfinance/9813358/British-taxpayers-funded-Irelands-14bn-bail-out.html

According to you, if Britain was not part of the EZ these bills mean nothing to Britain. I’m afraid I have to differ with you there.

@2slugbaits

The numbers used in this article are different, I assume these are tied to the same event mentioned in the Telegraph, if they aren’t, then it just only makes the British paid bailouts all the larger. I’m providing this one in case you get met with a paywall on the Telegraph link:

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2010/nov/22/ireland-bailout-uk-lends-seven-billion

The point here being, if British citizens keep being footed for the bill of EU bureaucracy and a disconnect between their vote and EU bureaucrats who make decisions on where British tax money goes, one can hardly be surprised if British voters have had it with being part of the EU, whether they have the same currency or not. This has in essence already been seen, as Brexit had been stalled over literally years, because the majority who voted FOR Brexit were being nanny-stated by being told that “they don’t know what is best for them, and parliament and Brussels do”. We do have Brexit now, already, and how you missed that I do not know.

https://www.vox.com/2020/1/31/21087676/brexit-timeline-boris-johnson-whats-next

In addition, it seems disingenuous for economists to say “Well they aren’t part of the EZ, so there’s no problem with status quo”. The point is everyone knew where it was going. And the more Britain’s economy is tied to the EU, the more bullying and manipulation of Britain’s sovereignty (and the future of its currency) was going to take place. And it’s very disingenuous for any economist not to recognize the fact that staying in the EU was a roadmap for eventual membership into the EZ.

Maybe we need a chart for Moses:

GBP to EUR Chart

https://www.xe.com/currencycharts/?from=GBP&to=EUR&view=10Y

Moses Herzog Okay, now I see where you’re going. I’m afraid you are misunderstanding things. Within the EU all member states are supposed to contribute to the EU budget, which is controlled by the EU Parliament. Some countries will contribute more than they get back at some point in time, but at another point in time that country might get more from the EU than they contribute. It’s no different here between the 50 states. The Brexiteers tried to sell the public on the notion that these EU taxes were an unfair burden on British taxpayers. Of course, Britain also had a vote in the EU Parliament, so it’s not clear how something is an unfair burden if the member countries (of which Britain was one) approve bailout packages. But note that Brexit only made matters worse. That’s because under the terms of the Brexit divorce the UK is still on the hook to pay into the EU fund but loses its vote in Parliament. It’s the worst of all possible worlds. It’s pay-but-no-play. I’m sorry, but you’re simply wrong about Brexit. There might be some emotional or non-economic reasons for wanting to get out of the EU, but as an economic issue it makes no sense at all. A generation from now Britain will be significantly poorer than it otherwise would have been. And since the UK’s rate of deaths per million population is on track with France and Italy when there were at the same point in time, it’s the UK that might be begging some of the other EU countries for a bailout. The British are going to have a very hard time trying to recover their economy without an export market. But I’m sure the British will die with a stiff upper lip while singing Rule Britannia and longing for the days of empire.

@ 2slugbaits

With all due respect, and only referring to this particular issue (as I respect your view on most issues), I’m sorry if I can’t take very seriously a man who didn’t even know Brexit had already officially occurred telling me I am “misunderstanding things”. And when you can show me the more extreme numbers that Menzie, London banks, and my “personal favorite” HM Treasury were quoting have come to reality, and are the lion’s share of these more extreme numbers (and not COVID-19 etc), then (and only then) I will wave the white flag. I don’t see that happening.

https://www.parliament.uk/documents/commons-committees/Exiting-the-European-Union/17-19/Cross-Whitehall-briefing/EU-Exit-Analysis-Cross-Whitehall-Briefing.pdf

The exit will be slow, and not near as melodramatic as HM Treasury or your overly imaginative mind would have us believe:

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/16/opinion/what-to-expect-when-youre-expecting-brexit.html

Moses Herzog: I would say Brexit has and hasn’t occurred, and possibly will not be fully implemented for a long time.

Moses Herzog who didn’t even know Brexit had already officially occurred

Well, that’s technically true in the sense that the 31 Jan 2020 date has passed; however, the current status resembles a kind of “sitzkrieg” moment. The deadline passed and then nothing happened because it was overtaken by events. I don’t know where you got this idea that I think Brexit will result in some kind of sudden collapse of the British economy. That’s a straw man argument. I thought I made it pretty clear that the effects of Brexit will take a generation to fully play out. In fact, here’s what I said in an earlier comment:

A generation from now Britain will be significantly poorer than it otherwise would have been.

@ Menzie

I will agree with you, there is a large gray area there. Now if I argued things like Barkley, I could be a d*ck about it, and say “it has officially happened” PERIOD, but that would be disingenuous and not tied to reality. But….. that slowness in implementation is also part of my point, and part of Krugman’s point and others. If these Brexit changes happen slowly it is all the less apt to be the nightmare that HM Treasury, some London banks, etc were portraying it was going to be. I have never argued that Brexit was going to hurt them to a degree in the short term. My argument was, it wasn’t going to be the severe numbers some were quoting, and that over the long term the increased British independence and “stronger tether” between the British voter and those making decisions deeply affecting the British population was a healthier and more democratic set up. Which, BTW, would set up for better economics long-term.

Moses Herzog: I think the impact of a “hard Brexit”, which is likely given the incompetence of the top UK leadership right now, is pretty negative. A good survey of estimates is in this PIIE working paper: https://piie.com/system/files/documents/wp19-5.pdf

I assign this paper as an optional reading to my public affairs international trade course.

Wow, Moses, you fall on your face making nonsense claims, and then drag me into it.

So, to be a bit more prcise about what Menzie and 2slug and others are saying, there was an official (Br)exit on Jan. 31, 2020, and it is manifested by such things as there now being no British members in the EU parliament ot its other decisionmaking bodies. However, many of the most important details regarding the exit, especially regarding what trade arrangmenrs will be between the EU and UK, remain unresolved and in place. Supposedly these are all to be resolved by a year after the Brexit, that is, on January 31, 2021. But we shall have to see iif that can be managed or hot as deep disagreements remain.

As it is, many have noted that the UK continues to be subject to a rather long list of rules and restrictions of the EU, but no longer has any say in them, given the absence of its representatives from the decisionmaking bodies of the EU.

Frankly, you need to step back here, and also, frankly, you owe several people an apology. You have been seriously wrong as well obnoxiously pompous about. Not for the first time.

@ Menzie

I greatly appreciate the Peterson Institute link Menzie, and will try to read it tonight.

That’s right, Moses, what 2Slug says is exactly right. All of your boldings in this last comment just remind anybody who knows anything about this that Duke U. should be profoundly embarrassed for having granted incompetent you an undergrad degree in finance. Really.

The UK never left its currency – the pound, which floats with respect to the Euro. Which was a good thing about a decade when the Bank of England ran a more expansionary policy. Of course fiscal policy back then turned to austerity. Simon Wren Lewis covered all of this at his excellent blog.

Thank you Captain Obvious.

Dear Folks,

This is not a direct response to Ashoka Mody’s very reasonable argument. It is just a question about whom the “strong” economies might be. Dr. Mody is taking the U.S. as “strong”, and it might not be, and lending to Italy will be a difficult position to take domestically.

Danielle Allen has a piece in The Washington Post today, referring to a white paper that she and colleagues at Harvard have prepared. The white paper is available at

https://ethics.harvard.edu/files/center-for-ethics/files/whitepaper_2_-_when_can_we_go_out_3.25.20_1.pdf

The argument in the white paper is unproved. But it may be the case that countries who deal with the virus effectively, as opposed to countries with the largest GDPs, will be the “strong” countries. Denmark, if Danielle Allen’s argument is valid, might be one of those countries. So the European Parliament might be the one facility that deals with Italy effectively, or possibly the Asian countries, as the U.S. avoids involvement, out of lack of “strength”.

Julian

Here’s another way to “chart the crisis”:

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/27/business/economy/coronavirus-inequality.html?action=click&module=Spotlight&pgtype=Homepage