Today, we are fortunate to have a guest contribution written by Olivier Coibion (UT Austin) [interviewed here by Prakash Loungani], Yuriy Gorodnichenko (UC Berkeley), Lorenz Kueng (Northwestern) and John Silvia (Wells Fargo); it is based on IMF Working Paper No. 199

“In recent decades, the Fed has given way completely, at the highest level and with disastrous consequences, when the bankers bring their influence to bear… As the American economy begins to improve, influential people in the financial sector will continue to talk about the need for a prolonged period of low interest rates. The Fed will listen. This time will not be different.”

Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson in “Who Captured the Fed?” 3/29/2012

Recent popular demonstrations such as the Occupy Wall Street movement have made it clear that the high levels of inequality in the United States remain a pressing concern for many. While protesters have primarily focused their ire on private financial institutions, the Federal Reserve (Fed) has also been one of their primary targets. The prevalence of “End the Fed” posters at these events surely reflects, at least in part, the influence of Ron Paul and Austrian economists who argue that the Fed has played a key role in driving up the relative income shares of the rich through expansionary monetary policies. But this view is not restricted to Ron Paul acolytes. As the quote above from Acemoglu and Johnson illustrates, the notion that expansionary monetary policy primarily benefits financiers and their high-income clients has become quite prevalent. For example, Mark Spitznagel (2012), a prominent hedge fund manager, recently published an Opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal titled “How the Fed Favors the 1%.”

Possible Channels Linking Monetary Policy and Inequality

Proponents of this view focus on two channels through which monetary policy affects inequality:

- Heterogeneity in income sources: While most households rely predominantly on labor incomes, for others financial income, business income or transfers may be more important for others. If expansionary policy raises profits by more than wages, wealth will tend to be reallocated toward the already wealthy.

- Financial market segmentation: Money supply changes are implemented through financial intermediaries. Increases in the money supply will therefore generate extra income, at least in the short-run, for financiers and their high-income clients.

However, there are in principle a number of other channels through which monetary policy could also affect inequality:

- Portfolio effects: If some households hold portfolios which are less protected against inflation than others, then inflation will cause wealth redistribution. For example, low-income households typically hold a disproportionate share of their assets in the form of currency.

- Heterogeneity in labor income responses: Low-income groups tend to experience larger drops in labor income and higher unemployment during business cycles than high-income groups.

- Borrowers vs. Savers: Higher interest rates, or lower inflation, benefit high net-worth households (savers) at the expense of low net-worth households (borrowers).

While the portfolio channel goes in the same direction as those emphasized by Austrian economists, the other two channels point to effects of monetary policy that go precisely in the opposite direction: contractionary –rather than expansionary– monetary policy will tend to increase inequality.

What Does Monetary Policy Actually Do to Inequality?

In light of these different channels, the effect of monetary policy on economic inequality is a priori ambiguous. In a recent working paper (Coibion, Gorodnichenko, Kueng and Silvia 2012), we study how inequality responds to monetary policy shocks and which channels drive these dynamic responses. Our measures of inequality come from detailed household-level data from the Consumer Expenditures Survey (CEX) since 1980. While the CEX does not include the very upper end of the income distribution (i.e. the top 1%) which has played a considerable role in income inequality dynamics since 1980, the detailed micro-data do allow us to consider a wide range of inequality measures including for labor income, total income as well as consumption. In addition, the CEX is available at a higher frequency than other sources.

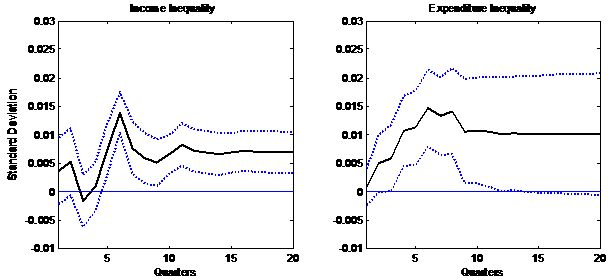

Using these measures of inequality, we document that monetary policy shocks have statistically significant effects on inequality: a contractionary monetary policy shock raises inequality across households. Figure 1 below illustrates the impulse responses (and one standard deviation confidence intervals) for total income and total household expenditures, where inequality is measured using the cross-sectional standard deviation of logged levels, to a contractionary monetary policy shock.

Figure 1: Responses of income and expenditure inequality across households.

These results are robust to the time sample, econometric approach, and the treatment of household observables and hours worked. Thus, the empirical evidence points toward monetary policy actions affecting inequality in the direction opposite to the one suggested by Ron Paul and Austrian economists.

Why Does Economic Inequality Rise after Contractionary Monetary Policy?

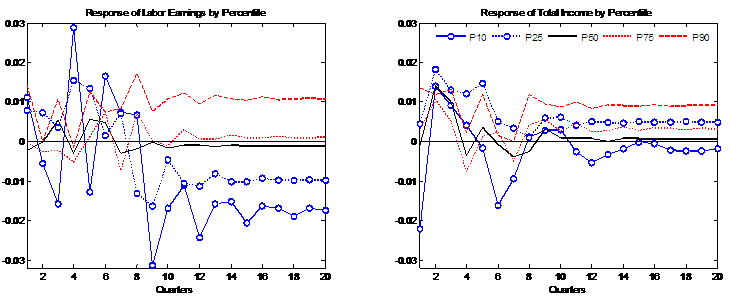

Because of the detailed micro-level data in the CEX survey, we can also assess some of the channels underlying the response of inequality to monetary policy shocks. For example, Figure 2 below plots the responses of different percentiles of the labor earnings distribution in response to contractionary monetary policy shocks.

Figure 2: Response of labor earnings and total income by percentile

Monetary policy shocks are followed by higher earnings at the upper end of the distribution but lower earnings for those at the bottom. Thus, there appears to be strong heterogeneity in the responses of labor earnings faced by different households. Strikingly, the long-run responses of labor earnings and consumption (not shown) for each percentile line up almost one-for-one, pointing to a close link between earnings and consumption inequality in response to economic shocks. Thus, heterogeneity in labor income responses appears to be a significant channel through which monetary policy affects inequality.

Figure 2 also plots responses of total income, defined as labor income and all other sources of income, after a contractionary monetary policy shock. While the responses of total income at the upper end of the distribution are almost identical to those for labor earnings, those at the 10th and 25th percentiles are shifted up significantly. This reflects the fact that lower quintiles receive a much larger share of their income from transfers (food stamps, Social Security, unemployment benefits, etc.) and that transfers tend to rise (albeit with a delay) after contractionary shocks, thereby offsetting lost labor income. Hence, transfers appear to be quite effective at insulating the incomes of many households in the bottom of the income distribution from the effects of policy shocks. As a result, the dynamics of total income inequality primarily reflect fluctuations in the incomes of households at the upper end of the distribution. This illustrates that the income composition channel, particularly for low-income households, is also a key mechanism underlying the effects of monetary policy on income inequality.

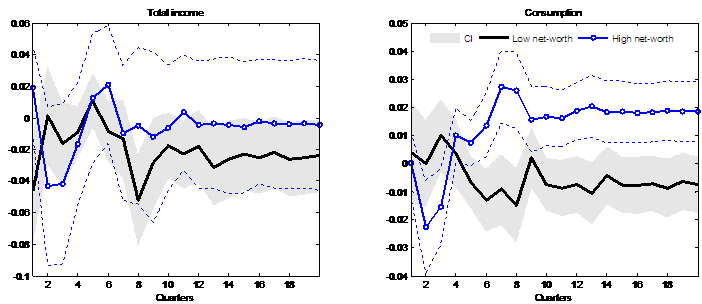

Because the CEX does not include reliable measures of household wealth, it is more difficult to assess those channels that operate through redistributive wealth effects rather than income. For example, in the absence of consistent measures of the size of household currency holdings or financial market access, we cannot directly quantify the portfolio or financial market segmentation channels. Nonetheless, to the extent that both channels imply that contractionary monetary policy shocks should lower consumption inequality, the fact that our baseline results go in precisely the opposite direction suggests that these channels, if present, must be small relative to others. However, in the case of the redistributive channel involving borrowers and savers, we can provide some suggestive evidence of wealth transfers by identifying high and low net-worth households as in Doepke and Schneider (2006), namely that high net-worth households are older, own their homes, and receive financial income while low net-worth households are younger, have fixed-rate mortgages and receive no financial income. As illustrated in Figure 3 below, while the responses of total income for the two groups are statistically indistinguishable, consumption rises significantly more for high net-worth households than low net-worth household after contractionary monetary policy shocks, consistent with monetary policy causing wealth redistributions between savers and borrowers.

Figure 3: Response of Income and Consumption for High and Low Net-Worth Households

Conclusion

While there are several conflicting channels through which monetary policy may affect the allocation of wealth, income and consumption, our results suggest that, at least in the U.S. between 1980 and 2008, contractionary monetary policy actions tended to raise economic inequality or, equivalently, expansionary monetary policy lowered economic inequality. To the extent that distributional considerations may have first-order welfare effects, our results illustrate the need for models with heterogeneity across households which are suitable for monetary policy analysis. In particular, the sensitivity of inequality measures to monetary policy actions points to even larger costs of the zero-bound on interest rates than is commonly identified in representative agent models. Nominal interest rates hitting the zero-bound in times when the central bank’s systematic response to economic conditions calls for negative rates is conceptually similar to the economy being subject to a prolonged period of contractionary monetary policy shocks. Given that such shocks appear to increase income and consumption inequality, our results suggest that current monetary policy models may significantly understate the welfare costs of zero-bound episodes.

References:

- Acemoglu, Daron and Simon Johnson, 2012. “Who Captured the Fed?” The New York Times Economix, [link].

- Coibion, Olivier, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Lorenz Kueng, and John Silvia, 2012. “Innocent Bystanders: Monetary Policy and Inequality in the U.S.” NBER Working Paper 18170, [link].

- Doepke, Matthias and Martin Schneider, 2006. “Inflation and the Redistribution of Nominal Wealth,” Journal of Political Economy 114(6) 1069-1097.

- Spitznagel, Mark, 2012. “How the Fed Favors the 1%,” Wall Street Journal, April 20th, 2012.

This post written by Olivier Coibion, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, Lorenz Kueng and John Silvia

Let me get this straight: a contractionary monetary shock (rising interest rates) hurts the poor who borrow and favors the rich who lend. And, an expansionary monetary shock (lowering interest rates) favors the poor who borrow and hurts the rich who lend. I sure hope that this paper was not funded by a governmental grant.

Reviewing the paper I saw much analysis on contractionary monetary policy creating income inequality but I only saw speculation concerning expansionary monetary policy. Where is the analysis of expansionary monetary policy on income inequality?

It is a mischaracterization of Austrian economics to say that because Austrians postulate that an expansionary monetary policy adds to income inequality and the study shows that a contractionary monetary policy adds to income inequality that the Austrians are wrong. Austrian economists would actually hold that either expansionary or contractionary monetary policy would lead to income inequality.

A serious analysis of monetary policy’s influence on income inequality would analyze expansionary periods, contractionary periods, and periods with neither.

Of course Schumpeter would say that income inequality is one of the elements that leads to economic growth so he would not hold that income equality should be government policy. Policies with the goal of income equality create wedges preventing economic growth.

Inflation reduces the value of money. It hurts those who have money and helps those who owe money at a fixed interest rate. The poor do not have much wealth or income, so tax breaks won’t help them and inflation doesn’t hurt them. An expansionary monetary policy is what they need to raise their incomes and reduce their debt.

I would think that the societal costs of monetary policy shocks, positive or negative, would fall disproportionately on those least able to make adjustments to thier savings/consumption and income decisions.

Capitalists reallocate physical and financial resources to minimize the effect of any shock, but labor’s resource allocation decision is less flexible. If so, then capitalists will tend to capture more of the gain and less of the cost.

I would have liked to have seen the same results for an expansionary shock.

Also – Given the transmission mechanism from FED to Agg Demand is broken, why doesn’t the FED just mail a 1.2 trillion dollar check to households? As it is, the 1+Trillion is sitting in excess reserves.

120 million households x $1,000 = $120 Billion.

120 million households x $10,000 = $1.20 Trillion.

Wouldn’t that be a more efficient way to ignite some inflation, reduce real rates, and incent capitalists to shift money from cash to productive uses?

At least the lower end gets $10K to cushion the effect of inflation, instead of having to wait for a lagged wage effect and try to catch up to output price increases.

Although this paper confirms what other papers have found concerning the negative effect of contractionary monetary policy on inequality via the earnings heterogeneity channel, its most significant result, in my opinion, is that concerning the impact of contractionary monetary policy on inequality via the capital income (dividends, interest and rent) channel (what the paper calls “financial income”). Pages 20-21:

“Second, these results suggest that the response of income inequality would likely be even more pronounced if the top 1% of the income distribution were included. This is because the source of income for the top 1% is quite different from that of other groups. The CBO (2011) reports that the top 1% received only 40-50% of their total non-capital gain income from labor earnings between 1980 and 2007 while financial income and business income accounted for approximately 30% and 20% respectively. Because financial income rises persistently while business income declines only briefly after contractionary monetary shocks, and because their labor earnings are likely to rise at least as much as the 90th percentile, one can reasonably speculate that the total income of the top 1% would rise by more than most of the households in the CEX.”

The CBO publication noting the fact that capital income accounts for approximately 30% of the income of the top 1% is here. Note pages 16-19:

http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/10-25-HouseholdIncome.pdf

Capital income was almost never more than 14% of total personal income during the age of accelerating inflation from 1965 to 1980 but has always been higher during the era of disinflation.

Thus, this passage, from the conclusion:

“Nominal interest rates hitting the zero-bound in times when the central bank’s systematic response to economic conditions calls for negative rates is conceptually similar to the economy being subject to a prolonged period of contractionary monetary policy shocks. Given that such shocks appear to increase income and consumption inequality, our results suggest that standard representative agent models may significantly understate the welfare costs of zero-bound episodes.”

seems supported by this graph of the evolution of the shares of capital and labor income during the recovery:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?graph_id=83805&category_id=0

I have some questions for the authors, inspired by some questions I have been heard concerning this paper. (Hopefully they can be answered.)

1. Where can one find the VAR model estimates?

2. Are the quarterly Gini Coefficients calculated directly from the Consumer Expenditure Survey data?

3. Gini Coefficients tend to non-stationary (have unit roots). In such a case shouldn’t a VAR be estimated only if the data is cointegrated? I couldn’t find any discussion of these problems in the paper.

Some quick replies from one of the authors:

JLR: This is only one of several channels via which monetary policy affects the distributions. It is a priori theoretically ambiguous which effects will dominate.

TJ and Ricardo: We use both expansionary and contractionary shocks to construct responses (the paper plots the specific shocks). Responses to expansionary shocks are symmetric. We tested and could not reject the null of symmetric effects for expansionary and contractionary shocks.

Mark: Impulse responses come from single-equation estimates, not a VAR. We do not report the point estimates since, by themselves, they are not particularly interesting. Instead, we plot the dynamic responses implied by these point estimates. Quarterly Gini and other measures of inequality come from the CEX, for which data begins only in the early 1980s.

Thanks ocoibion. I actually searched the paper for the word “expansionary” and the root “sym” but found no reference to the symmetry between expansionary and contractionary shocks. Interesting results, nonetheless.

What about the time between shocks?

Is inflation the same as monetary policy shocks? Simply because they both are by-products of monetary policy actions does not make them the same.

Quick look at historical inflation rates shows that since 1980, annual inflation rate (CPI-U) is positive 29 out of 30 times. However, looking at the graph of monetary policy shocks variable (FIGURE 2 of the paper: MONETARY POLICY SHOCKS) since 1980 the shock variable changes in very different manner.

The paper seems to be set to discredit “that the Fed has played a key role in driving up the relative income shares

of the rich through expansionary monetary policies.” The quoted statement clearly refers to expansionary monetary policy, implying inflation resulting from it; however, then the paper analyzes monetary policy shocks, another effect of monetary policy.

In its conclusion the article again appears to draw implicit equivalence between these two different effects by folding them into the rubric of “monetary policy actions”. How can you disprove one effect of monetary policy by analyzing another one?

But you know, even when M1/M2 are increasing, if money is stack at the vault of the federal researve, then money in the real economy is NOT increasing. Money is increased only when the commercial banks make creidts or the federal government trade bonds for the federal researve notes newly printed, and then the government use it to pay for the workers or hand out to the public. This sort of idea should be in the model to address what Austrian economics and Ron Paul say about the monetary policy.

As I stated Schumpeter held that inequality was one of the most important elements in economic growth. Though there might be inequality between quintiles within the same economy economic growth brings all economic quintiles to a more prosperous level. The US is a great case on point. While there might be greater differences between quintiles in the US compared to the rest of the world the lowest quintile in the US is greater than the upper quintiles in other countries.

Here you can find a study by Brian Domitrovic that demonstrates that the very idea of taxation to gain income equality is detrimental to economic growth and to all economic levels. One of the problems I have found with the left is that they are always willing to trade away economic wellbeing for some perceived social gain. Leftist ideas always lead to economic decline and that leads to social decline. Leftist policies are false promises.

Excerpt:

Many studies have been made assessing such costs, and numbers in the hundreds of billions

of dollars in foregone output are the norm as the bottom line. Yet perhaps the most telling

statistic is as follows: Prior to 1913, the year the income tax (as well as the Federal Reserve)

came into being, the American economy grew at an annual rate of about 4% per year. Since

1913, that rate has been 3.2%.

That differential, of 0.8%, proves enormous. Had the U.S. economy continued to grow at

a 4% rate, it would be more than double the current size. Since invariably some portion

of that tremendous foregone growth would have accrued to the lower classes—even at an

unequal rate—we can say with credibility that had conditions not changed in 1913, the poor

and middle class would be better off today. The very mechanism for reducing inequality, the

progressive income tax, contributed to a precipitous decline in the trend of living standards

for those not at the top of the income scale.

This is a rich irony, and one not at all lost on those who devised the income tax. In what

follows, the early history of the income tax will be discussed as an illustration of the pitfalls

of addressing inequality matters through means of onerous progressive taxation. This

will bring us to the great base year of the Piketty-Saez research, 1960, the peak of income

equality and social leveling—and also a recession year marking the end of a dismal dozen

years of subpar growth. In turn, we shall follow the vagaries of the Piketty-Saez research as

it aims its fire on the Reagan and George W. Bush tax cuts, and see if the research skips over

imperative issues of what income and equality really are.