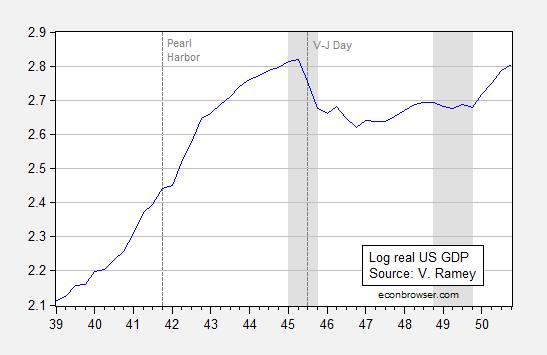

For a last bit of “Year in Review”, yet more “Facts are Stupid Things”. Patrick R. Sullivan asserts that the economy boomed once the government reduced its spending in the wake of World War II. I am going to take a “boom” as a rapid increase in economic activity. Here is a time series depiction of real GDP’s evolution, using the Valerie Ramey (UCSD) series from her 2011 QJE paper (ungated working paper version here).

Figure 1: Log real GDP index (2005=100). NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: V. Ramey, NBER, and author’s calculations.

So…output fell, and actually hit bottom in 1946Q4.Output does not re-attain levels at 1945Q3 (V-J day) until 1950Q3. Per capita output does not exceed V-J day levels until 1952Q4.

So, the proposition the economy boomed can be resurrected by defining “up” as “down”. Now, consumption does rise, but — as shown in the figure — economic activity overall moves in the fashion consistent with the proposition that a large decline in government spending ceteris paribus induces an output decline.

How can learning occur if one can’t agree on the facts…?

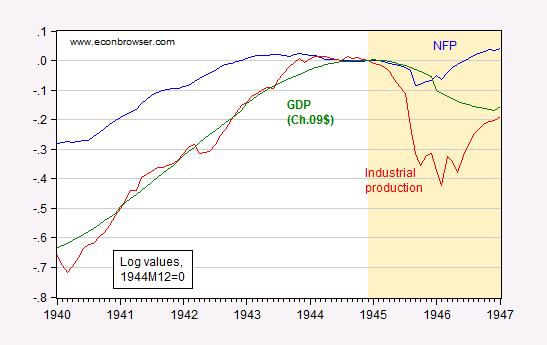

Update, 1/2/2015, 11:20AM Pacific: Reader Rick Stryker is concerned about controlled prices distorting real GDP measures. Well, here are some additional indicators in a graph drawn from the original post. The industrial production index does not incorporate prices in the same way that GDP does.

Figure 2: Log nonfarm payroll employment (blue), log industrial production (red) and log real GDP measured in Ch.2009$ (bold green), all normalized to 1944M12=0. Real GDP interpolated using quadratic-match-average. Tan shaded area is 1945 onward. Source: BLS and Federal Reserve via FRED, and Measuring Worth, and author’s calculations.

Now, I don’t mean to say the Nation is worse off even thought industrial production is lower in 1946. But, from the perspective of economic activity (which was the impetus of the original discussion of Keynesian economics), I’d say down is …well… down.

By the way, Rick Stryker writes approvingly of Ramey’s paper (the same one), as well as Barro’s, both cases using data spanning WWII. Mysterious and mysteriouser.

It’s not the facts that are the problem; it’s the definitions.

Some myopic economists define economic activity strictly as GDP, of which all government spending, no matter how wasteful or destructive, is a direct input. Pay an army of bureaucrats to harass and hinder citizens from going about their daily lives? That’s an economic boom!

Massive world war blowing up infrastructure and killing people? Awesomest economy ever!

Obviously GDP declines at the end of a war when what GDP measures is war spending.

W.C. Varones: Well, personally, I count every dollar spent blowing up German and Japanese tanks, warplanes and warships as a dollar well spent, call me crazy. I guess we’ll agree to dis-agree on this one.

Menzie, your trifling with evil midgets. The pareto-optimal stance would be to ban high-word-count, low-value commenters like Patrick and Varones. In the present case, one posted a falsehood and the other backed him up by claiming it’s perfectly ok to leave out evidence you don’t like. Allowing them to comment here provides a forum for what is clearly an effort to dilute honest discussion.

One big problem for policy is that large parts of the public can be led to believe things that are simply untrue. That has been the case with economic policy, global warming, death panels, causus belli for the 2nd Iraq war. Giving space to those who foster public ignorance contributes to the problem.

I do not advocate shutting off honest disagreement and debate, but the record of pure partisan dishonesty from some of your trolls extends for years. Do your patriotic duty. Stop providing a forum for those who willfully hurt our country.

The claim the economy boomed because government spending decreased at the end of WWII is one of the old chestnuts. In context, there had been consumer rationing and a huge shift to war production and, often ignored, a huge suppression of household formation with all the attendant household needs, so of course there was a large investment increase and a lot of production. But the idea this burst of activity is due to elimination of government spending is so completely idiotic its lunacy explains why the chestnut survives: of course there was a shrinking of government spending and of government generally because the bleeping war ended (and we won so our productive capacity survived, as opposed to being obliterated). To say that means anything else is so hugely freaking dumb, the claim falls into the category of “so ridiculous people don’t think about what the words actually mean” because no one believes someone would ever say something that stupid.

This is a version of the old “big lie”, the idea that a lie can be so hugely monstrous people believe it must be true because no one say something so completely wrong.

Can you explain this to me? It appears that GDP in your graph grows from 2.15 in 1939 to 2.65 in 1947, an increase of 23%, or about 3% per year.

If I take BEA data using chained 2009 dollars, GDP increases by 67% over this period, representing a 6.6% annual growth rate in constant dollar terms.

Why the difference?

Steven Kopits: Figure 1 has a vertical scale in logs. The cumulative percentage change in log terms is then 50% (<== 2.65-2.15 = 0.50). I don't know which BEA series in Ch.2009$ you are using, so I can't cross check (the official series I know of starts in 1947).

Yeah, OK, this was my misunderstanding.

So then we could say that, even if we remove transitory impact of WWII, US GDP increased by 50% from 1939 to the trough of the recession in 1947.

We are now coming out, to my way of thinking, another depression. What parallels might the post-1939 period have for our own expectations?

And a bit on Greece, where the macro trends don’t appear to be too bad.

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2015/1/1/greeces-economic-outlook

I for one, am delighted that Menzie has resolved to be as big an ass in the new year as he was in the one just ended. As I pointed out back in the day, Menzie’s argument is with the NBER, not with me;

http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html

Patrick R. Sullivan: I am still waiting to hear you admit you were in error regarding depth of the downturn in Canada vs. US during the Great Depression. As you recall, you stated unequivocally:

And this statement is wrong.

Happy New Year!

Patrick R. Sullivan: Oh, and at least in my book, “boom” ≠ “expansion”

Good to see you finally admit that this is merely you quibbling over semantics. Of course, (and since I never used the word ‘boom’, that was someone else), I pointed that out to you at the time.

The NBER dated the economic expansion from the time when federal govt. spending took a drastic downward plunge. Contrary to Keynesian dogma.

Btw, has James Hamilton made any New Year’s resolutions, like say, disassociating himself from political hacks masquerading as economists?

Patrick R. Sullivan: Yes, that somebody (Ed Hanson) asked if there was ever a boom when government spending was cut, and you immediately offered the date “September 1945”. So you implicitly said the boom started in 1945. Or is that too many links in the chain of logic for you to absorb? Seems pretty clear to me. And not merely a matter of semantics.

So, let me take this opportunity to note that I am still waiting to hear you admit you were in error regarding depth of the downturn in Canada vs. US during the Great Depression. As you recall, you stated unequivocally:

And this statement is wrong.

We need to move towards a 1995-00 economy rather than a 1940-45 economy.

There’s abundant labor and capital to expand the economy.

We need to promote entrepreneurship and work, to employ massive idle resources.

Here are some excerpts from 2014 articles:

“Information technology and personal computing have upended the technology market in recent decades…longtime market leaders have found themselves facing stiff competition from innovative upstarts. That led to the development of new technologies, greater productivity and job creation… the “creative destruction” process (is) needed to develop new innovations, force productivity gains, disrupt markets and match workers with firms more effectively.

What happened to all the entrepreneurs?

“We do not have an explanation,” write the University of Maryland and the Census Bureau economists. Neither does Litan. “One theory is that the cumulative effect of regulations,” he says, discriminates against new businesses and favors “established firms that have the experience and resources to deal with it.” What allegedly deters and hampers startups is not any one regulation but the cost and time of complying with a blizzard of them.

Brookings researcher Robert Litan and economist Ian Hathaway… found that “business deaths now exceed business births for the first time in the thirty-plus-year history of our data.

Competition among firms, write the economists, raises productivity. More efficient firms drive out the less efficient. One study attributes 35 percent of productivity gains to this “churning” of firms; the fall in startups dampens these improvements.

What’s happening now is that the economy is increasingly dominated by older firms tied to proven products and familiar business methods. In a new study, he and Ian Hathaway measured the age of U.S. businesses. They were astonished by what they found: From 1992 to 2011, the share of U.S. firms that were 16 and older jumped from 23 percent to 34 percent.

From 1978 to 2011, startups fell from about 15 percent of all firms to 8 percent; the slide was gradual until the 2008-09 financial crisis, when it accelerated…The economy needs the employment boosts of startups.”

Peak Trader, is there start up money? Has the recession and the ensuing regulations accomplished a go slow/low risk funding environment?

CoRev, I think, it has become harder to grow a new business.

It may not be worth the risk, and aggravation, to more people, even with the low cost of capital.

More customers and less crony-capitalism would help.

CoRev and Peak Trader – please cite any studies that document the increased cost of regulations over time – especially in the last six years – and how that has slowed down or impeded start ups. I suspect there are multiple reasons, not just one for the decline in start ups .

The SBA study from 2008 estimated federal regulations (not including state regulations) cost $1.7 trillion a year.

A new regulation that began in California yesterday is expected to raise gasoline prices another $0.10 a gallon (the low estimate).

Regulations raise costs and prices.

Of course, we need some regulation. However, the economy cannot absorb or afford too much regulation.

Has the cost of regulations increased in the last six years? For a start up. what is the cost of regulations as a percentage of total costs?

We added more regulations over the past six years, e.g. in Obamacare, Dodd-Frank, the EPA, etc..

Additional costs affect small businesses directly or indirectly.

In other words, welcome to France!

Who was it that promised to “transform America?” Mission accomplished!

Peak, entrepreneurship is associated with peak demographics, risk taking, earnings, spending, and wealth accumulation, which in turn is dependent upon the increase in the change rate of growth of those age 40-54. The trend rate of growth for this cohort is down into the early to 2020s. Therefore, we are likely to see ongoing weak, or no, growth of entrepreneurial activity, start-up creation, self-employment, and growth of private full-time employment for the next 5-10 years, eventually settling at a much slower trend rate of real potential GDP than we have experienced for the past 60-100 years.

Menzie,

I’m afraid I have to call this one for Patrick R. Sullivan.

Here at the Department of Free Market Economics at Wossamotta U, we have a fact checking service in which we assign between 1 and 4 Borises, depending on the degree of falsehood of the article or blog post we review. (We award Natashas if the article’s author is female.) I regret that I must award 3 Borises to this post, meaning that it is wrong in materially important respects.

Claiming victory by comparing a real GDP series during and after WWII is the last refuge of an unrepentant Keynesian economist. Keynesian economists at the time were not saying that “economic activity overall moves in the fashion consistent with the proposition that a large decline in government spending ceteris paribus induces an output decline.” In the face of perhaps the largest drop in government spending in US history, they were predicting economic disaster. Here’s what prominent Keynesian economist and Nobel Prize winner Paul Samuelson had to say in 1943 in “Full Employment and the War:”

“When this war comes to an end, more than one out of every two workers will depend directly or indirectly upon military orders. We shall have some 10 million service men to throw on the labor market. We shall have to face a difficult reconversion period during which current goods cannot be produced and layoffs may be great. Nor will the technical necessity for reconversion necessarily generate much investment outlay in the critical period under discussion whatever its later potentialities. The final conclusion to be drawn from our experience at the end of the last war is inescapable–were the war to end suddenly within the next 6 months, were we again planning to wind up our war effort in the greatest haste, to demobilize our armed forces, to liquidate price controls, to shift from astronomical deficits to even the large deficits of the thirties–then there would be ushered in the greatest period of unemployment and industrial dislocation which any economy has ever faced. ”

And yet the war did end suddenly and the economy, which was a centrally-planned command and control war economy with price controls, reverted very quickly to a mostly free market peacetime economy. The large drop in aggregate demand that the Keynesians expected, along with the economic catastrophe they believed must result, didn’t happen. True, the unemployment rate went from 1.9% in 1945 to 3.9% in 1946, but that’s still very low–hardly “the greatest period of unemployment … which any economy has ever faced.” Nearly 10 million people from the military were absorbed into the economy very quickly.

If you talk to people who were around right after WWII, as I have, you’ll find that they agree with Patrick R. Sullivan that the latter part of the 1940s was a boom. Why would they say that? Suddenly, goods and services were available. Price controls were lifted, rationing was stopped, and goods that were outlawed were now legal to produce. People could now get food, clothing, autos and other items that weren’t available during the war. Most people who wanted jobs could get them, with the unemployment rate being relatively low–not the double digit levels of the Great Depression.

Now how do we square the subjective impressions of people at the time with the real GDP data series that Menzie has posted? While Valerie Ramey did a very good job constructing the data series that Menzie used for this post, it does have some severe problems in comparing WWII and post-WWII output. You can’t really easily compare the output of the economy during the war to the output after the war, since radically different economic regimes were in place. During the war, the US economy had shifted to a centrally planned economy in which production was redirected to military goods. Price controls and rationing were in force and the economy was controlled from Washington. After the war, the economy was quickly and massively deregulated. In 1946, price controls were lifted and prices shot up. Suddenly higher prices will make real GDP in 1946 and after appear to be lower than it really was compared to periods in which prices were kept artificially low. But there is an even larger conceptual problem. GDP after the war measured output at market prices. But during the war, a great deal of GDP was not measured at market prices, since many prices were controlled and production that was centrally planned for war output was not valued at market prices at all. Thus, you can’t really fairly compare output during and after the war.

However, people at the time believed that there was a boom after the war. That makes sense. In the absence of rationing and price controls, and with the end of central planning, people could make many more mutually beneficial trades. Economic welfare dramatically increased. But that’s not what the Keynesians expected. They expected massive unemployment, civil unrest, and the need for a New New Deal to shore up aggregate demand. Keynesian economics failed. Its proponents must live with the infamy and shame of that failure while those who put their faith in the power of the unfettered market can bask in the warm glow of vindication once again.

Happy New Year Menzie and to all econbrowser readers!

‘If you talk to people who were around right after WWII….’

If you can’t, get a DVD of ‘The Best Years of Ours Lives’.

Otherwise I can’t improve on Rick’s analysis of the problems with Menzie’s semantic quibbling. Also, Valerie Ramey herself notes the problems with the WWII era data. Menzie ought to think about what she’s had to say in this paper that he amusingly thinks supports his prejudices.

Patrick R. Sullivan: You keep on mentioning this movie; I’ve seen it multiple times. So what? My dad was around at the end of WWII. I talked to him. Is this proof by anecdote?

I am still waiting to hear you admit you were in error regarding depth of the downturn in Canada vs. US during the Great Depression. As you recall, you stated unequivocally:

And this statement is wrong.

The fact that the movie was made in *1946* isn’t a clue, Menzie?

Patrick R. Sullivan: I know it’s from 1946… but I don’t recount my Dad’s stories from 1946 about how tough it was, over and over again, and then say QED.

I am still waiting to hear you admit you were in error regarding depth of the downturn in Canada vs. US during the Great Depression. As you recall, you stated unequivocally:

And this statement is wrong.

Rick Stryker: I’ve added Figure 2 for you. The term boom came up in the context of economic activity post WWII, and the question of whether output ever rises when government spending declines. I didn’t set up that problematique — Ed Hanson and Patrick R. Sullivan did. They were critiquing the Keynesian multiplier. Now the issue has been elided to nostalgia about “The best years of our lives” (Sullivan must be one of the few who still has a DVD player — no need to buy the DVD, it’s often on TCM, and on one of the streaming services). If one wants to say people were happier post WWII than during, I’d agree. If one wanted to say output was higher post than during, I’d say no.

Maybe people were happy in 1946 because the minimum wage was $ .40/hr, and it was so easy to find work (captured in the 1946 movie).

Patrick R. Sullivan: I am still waiting to hear you admit you were in error regarding depth of the downturn in Canada vs. US during the Great Depression. As you recall, you stated unequivocally:

And this statement is wrong.

patrick,

“Maybe people were happy in 1946 because the minimum wage was $ .40/hr, and it was so easy to find work (captured in the 1946 movie).”

or maybe people were happy the previous decade of war and carnage had ended? getting a root canal in 1946 would have been considered a pleasant experience compared to any day in 1944.

Rick Stryker: I note some fella named Rick Stryker writes approvingly of Ramey’s paper (the same one that uses the aforementioned data), as well as Barro’s, both cases using data spanning WWII. Please comment.

W.C. Varones: “In other words, welcome to France!”

If only the U.S. were to be so lucky. France has a productivity per hour worked that rivals the U.S., even higher than Germany, yet the average person works less than 1500 hours per year. 30 days paid vacation per year, universal health care that is the best in the world, 16 weeks paid maternity leave, low cost college education, lower income inequality. Oh, and just so conservatives don’t feel left out, a lower debt to GDP.

What’s not to like?

Your statement is biased or incomplete.

For example, paying people $20 an hour 30 hours a week to dig holes and fill them up again inflates GDP, but living standards rise very little.

And, when you measure infant mortality rates the same way, control other factors, e.g. homicides, traffic deaths, etc., the U.S. has the highest average life expectancy in the world.

Just because the cost of education is lower doesn’t mean quality rivals U.S. standards.

France also has higher taxes and thousands of years of accumulated wealth.

For example, here’s what a MD stated:

The WHO healthcare rankings are worse than useless: they are outright lies. The WHO relies upon self-reporting from each nation. Does anyone believe that Cuba or China provide truthful data?

The WHO rankings also overemphasize “coverage” (where the US ranks very low since we have many uninsured people who have to pay at the time of service — gasp!).

The reason we have fewer MDs per capita than Europe is that our mostly self-employed doctors work 60-80 hours per week while government-employed European doctors work 35 hours per week. This is another worthless comparison that the WHO uses to slam the U.S.

The WHO also ranks the US low for neonatal deaths because we have the strictest reporting standards of any country in the world. If a 30-week-gestational-age premie dies after a week in the NICU, we call that a neonatal death. Most of Europe calls that the equivalent of a stillbirth: they pretend the premature baby wasn’t born alive.

Thomas Piketty says, there’s plenty not to like;

http://uk.reuters.com/article/2015/01/01/uk-france-economy-idUKKBN0KA1OT20150101?rpc=401&

‘Once close to France’s ruling Socialist party, Piketty has become very critical of Hollande. “There is a degree of improvisation in Francois Hollande’s economic policy that is appalling,” he told Le Monde daily in June.’

In fact, Jean Tirole did too.

Patrick R. Sullivan: I am still waiting to hear you admit you were in error regarding depth of the downturn in Canada vs. US during the Great Depression. As you recall, you stated unequivocally:

And this statement is wrong.

From article:

“The U.S. has the best record for five-year survival rates for six different cancers. In some cases the differences are huge: 81.2% in the U.S. for prostate cancer vs. 41% in Denmark and 47.4% in Italy; 61.7% in the U.S. for colon cancer vs. 39.2% in Denmark; 12% in the U.S. for lung cancer vs. 5.6% in Denmark.

Also interesting is the fact that there is often a significant difference between white and black cancer survival rates in the U.S., e.g. prostate cancer – 82.7% for whites vs. 69.2% for blacks. But even in that case, the five-year survival rate for blacks (69.2%) is still higher than for all European countries except Switzerland.”

Peak Trader – I am not due why you would decry coverage as a good thing for health care! Also, the percentage of primary care physicians who are self employed is 38% and all physicians 52% and that percentage has been on a downward slope for years. As for ignoring statistics from other countries, why do you then cite statistic from other countries. There are many countries who keep excellent records. We have fewer physicians because the supply is controlled.

Coverage is a good thing, although health care insurance is not the same as health care.

Why not increase health care instead?

Yes, the supply of U.S. medical schools or students is limited.

Are you saying that MD was wrong when he wrote (the U.S. has the) strictest reporting standards of any country in the world?

I am saying that there are many countries that have comparable health statistics – to say we are better than

Sweden makes no sense. We have a good system if you have access to it. “The United States’ ranking is dragged down substantially by deficiencies in access to primary care and inequities and inefficiencies in our health care system according to Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: How the Performance of the U.S. Health Care System Compares Internationally, 2014 Update, by Karen Davis, of the Roger C. Lipitz Center for Integrated Health Care at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; Kristof Stremikis, of the Pacific Business Group on Health, and Commonwealth Fund researchers Cathy Schoen and David Squires.”

Variable Rates of Five-Year Cancer Survival and Cancer Mortality in the U.S.

• From 2002 to 2007, the five-year survival rate for three cancers in the U.S. was relatively high among the eight countries reporting though the ranking varied by condition. For breast cancer, the five-year survival rate in the U.S. was 90.5 percent, the high- est among the eight countries reporting and 12 percentage points higher than the lowest performer (the U.K. at 78.5%). The five-year survival rate

for colorectal cancer was also highest in the U.S. at 65.5%, which was nearly 14 percentage points higher than the lowest performer (the U.K. at 51.6%). On cervical cancer, the U.S. (67.0%) ranked fourth out

of eight countries reporting, behind New Zealand (67.7%), the Netherlands (69.0%), and Canada (71.9%).

• The U.S. had middling-to-low rates of mortality

due to cervical cancer (2.1 per 100,000 population), breast cancer (20.7 per 100,000 population), and colorectal cancer (14.4 per 100,000 population). Of the nine countries for which data were available, only the U.S. and France had mortality rates below the median for all three types of cancer.

What we do know for sure is that our costs are by far the highest and for those costs we do not get overall higher outcomes than that of other developed countries

Our costs are high, because of regulations, lawsuits, unnecessary tests, etc.. Nonetheless, our outcomes are high.

For example, you cite cervical cancer. The screening rate for cervical cancer in the U.S. is the highest in the world (86%).

And, “In the U.S., African-American women have the highest rate of cervical cancer, followed by Hispanics, Caucasians, American Indian/Alaska Natives, and Asian American/Pacific Islanders. Mortality rates are highest for African American women.”

It seems, you want a health care system similar to the VA system, or worse.

peak, when the poor and minority populations disproportionately existed without health insurance, is it not logical they are not identified and treated? i think your statistics illustrate a bias between european countries who provide health care to their entire population, and a us system significantly dependent upon economic status for health care treatment-at least until the ACA arrived.

Menzie is the real pseudo-economist, disingenuously taking GDP at face value during exactly the period in US history when it most obviously can’t be taken at face value.

Surely all the war spending in WWII was money well spent. Nonetheless it was a very different kind of value than other components of GDP. The collapse of armaments spending as the war ended was not an economic collapse. It was glorious relief from being forced by fascists to throw most of our resources into things that brought no joy.

Of course a war economy can’t instantly transform into a civilian economy. The post-war boom that Patrick and Rick are talking about, and which people who lived during the time remember, was of the civilian economy, which underwent severe austerity during the war.

Trying to use the experience of WWII as a lesson of how public spending helps the economy and cutting public spending hurts the economy during a time of peace is deeply troubling. It implies that the writer would prefer a command economy even in peacetime.

I doubt if name calling contributes anything to the discussion. Please explain exactly how the money spent on armaments is of less value than money spent on infrastructure. Pointing out the results of spending and measuring the impact of the cessation of spending has nothing to do with proposing a command economy

Don’t pretend you didn’t understand me. I said different not less. And I might think armaments in WWII were more valuable, that’s neither here nor there. But in peace time you don’t face a choice between lots of collective spending on war or losing a war. You face choices about appropriate taxation levels, budget balances, and public spending levels. If your rule is as simple as, public spending should be increased because doing so elevated GDP during WWII, then there is never any situation when public spending shouldn’t be increased. Hence you’re implying a preference for maximum public spending, is a command economy. And you’re not an economist in my book, as you’re indifferent to efficient allocation of resources.

You are knocking down a strawman who does not exist. I don’t see anyone proposing maximum government spending. I am interested in looking at the impact of government spending on GDP in times of high unemployment and what happens when that spending is withdrawn. I do not pretend to be an economist but I am interested in what the results are from implementation of opposing policies. In times of depression or recession when the economy is contracting, which policies will boost growth and which will not. The contraction of the economies following the introduction of austerity policies in Europe, does not support the predictions that austerity in those circumstances would result in growth. Can you explain why? The reduction in government spending after WWII was as followed by a slow down in the economy. So austerity does not seem to always help. At full employment, no one is advocating increased spending.

Scrap the Call on OPEC, at Platts

http://blogs.platts.com/2015/01/02/opec-call-price-collapse/

Peak Trader – The studies I have seen do not support your statement that our cost are high because of litigation. If that were true, the cost in Texas after the introduction of tort reform would have been followed by a reduction in the cost. I can’t remember another the study I read, but it estimated the cost of litigation was under 2%. There is no doubt that regulations are a cost, but you have to separate regulations that improve out comes from those that do not. I know of no studies that measure those costs

Robert Hurley, U.S. health care is a $2.6 trillion a year industry.

Even the WHO, which ranked U.S. health care below Cuba, stated the U.S. is #1 in the world in both labor (doctors, nurses, specialists, etc.) and capital (hospitals, equipment, drugs, etc.).

Yet, U.S. medical malpractice insurance is high.

And, Washington D.C. may have more lawyers than Texas 🙂

Menzie,

Your additional charts just illustrate further what I’m saying. The drop in industrial production, for example, reflects the very rapid reduction of military expenditures following cessation of hostilities in May 1945 in Europe and in September 1945 in the Asian theater. As I mentioned previously, the US had transitioned to a war economy and most of industrial production was dedicated to the war effort. The October 1943 Federal Reserve Bulletin has an interesting discussion of the industrial production index, which had been revised in 1939. For example, the Fed quantified the amount of industrial production going to war output:

“It appears that currently about 70 per cent

of industrial production is going for war purposes,

including munitions and supplies used by

the armed forces, exports under Lend-Lease, and

also the industrial equipment and materials

produced to make these finished products. The

remaining 30 per cent of total industrial output

constitutes goods produced for civilians; this

proportion of the present greatly enlarged output,

however, represents as much as 70 per cent

of average production for civilians in 1935-39.”

Like real GDP, industrial production has its problems as well in measuring wartime output, as discussed in the section “Special problems in measuring wartime output” of the 1943 Fed document.

Once hostilities ended in 1945, there was a very rapid reduction in war output, which is what the industrial production series is showing. For example, the July 1945 Federal Reserve Bulletin noted that:

“Adjustments to the changed war situation

had been inaugurated in anticipation of the

actual cessation of hostilities on May 8.

Volume of munitions output in March,

which was the last month of production

under the full two-front war program, was

107 per cent of the 1943 average, according

to the War Production Board’s index.

Munitions production declined 5 per cent in

April and decreased further in May to a

point about 15 per cent below the wartime

peak reached at the end of 1943. Output

of aircraft, ammunition, and combat and

motor vehicles, which had increased from

last autumn to March, has declined since

that time. Activity at shipyards, which by

March had been curtailed considerably, has

been reduced further since then and in May

was about 40 per cent below the peak level

at the end of 1943.”

The October 1945 Federal Reserve Bulletin reported that:

“The production and employment at factories dropped

sharply after the middle of August when

most military contracts were canceled. Activity

in most other lines was maintained and

the value of retail sales continued above last

year’s high levels.

Industrial production declined 11 per cent in

August, reflecting primarily the sharp curtailment

of activity in aircraft, shipbuilding and

ordnance plants in the last half of the month,

and the Board’s seasonally adjusted index was

188 per cent of the 1935-39 average as compared

with 211 in July.”

Interestingly, the December 1945 Federal Reserve Bulletin noted the burgeoning rapid transition from wartime to peacetime production:

“War production was curtailed

rapidly upon the cancellation of war

contracts and total industrial output

dropped by about one-fifth from the early

part of August to the early part of October.

Since that time production at factories and

mines has increased, employment has expanded

in industry as well as in the services

and trades, and consumer incomes have held

at the level which prevailed during most of

1944.

To a large extent the reduction in Federal

war expenditures since August has been

offset by increased private expenditures for

goods and services. Business orders and

purchases of raw and semifinished materials

and finished products for capital purposes

and of goods to sell at retail to consumers

have been in exceptional volume. Value

of contract awards for construction of

manufacturing facilities has been at the

highest level on record. Awards for commercial

building and other private nonresidential

building have also increased

sharply; residential awards increased substantially

in the second half of October,

after the removal of restrictions…”

Industrial production was elevated and dominated by war production. When that war production was rapidly decreased in 1945, industrial production not surprisingly fell. What was surprising to the Keynesians of the time, however, was that the economy made a very rapid transition to peacetime production without the need for any stimulus. The calamity they expected didn’t happen. This episode in history is a stark repudiation of the Keynesian view.

I don’t understand your point about my previous Ramey comments. I think the paper I commented on is excellent and I very much admire Ramey’s work in general. I was only asking critics like Krugman or his acolytes who comment on this blog not to dismiss Barro or Ramey by claiming that WWII was unrepresentative without any additional argument as to why that matters. Because if you really look into the details-real GDP is likely measured too low after 1946 because of price controls for example–it only strengthens Ramey’s conclusions.

I am also just reminding people of the distinction between real GDP and economic welfare. They are not the same of course.

Rick Stryker: Are we disagreeing? Notice your quote about “…middle of August when

most military contracts were canceled.” In the extreme Fama view of the world, for instance, each dollar released from government spending would have been instantly reallocated to private spending, so GDP would be unchanged. Neither Ramey, nor your argument, go this distance. And that is good, because GDP did go down (or do you disagree with Ramey’s series?).

So, if you want to argue about the validity of the estimates of multipliers estimated over wartime periods, I can see an actual debate there.