Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution by Yi Zhang, Ph.D. candidate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. This post draws upon this paper.

Since 1982, the Fed has targeted the federal funds rate as the primary instrument of monetary policy. But from late 2008 onward, the federal funds rate has been effectively bound at zero, so that lowering it further to stimulate the economy has become infeasible. Consequently, the Fed implemented unconventional policy tools such as large-scale asset purchases (LSAPs) and forward guidance in order to affect long-term interest rates thereby stimulating the economy.

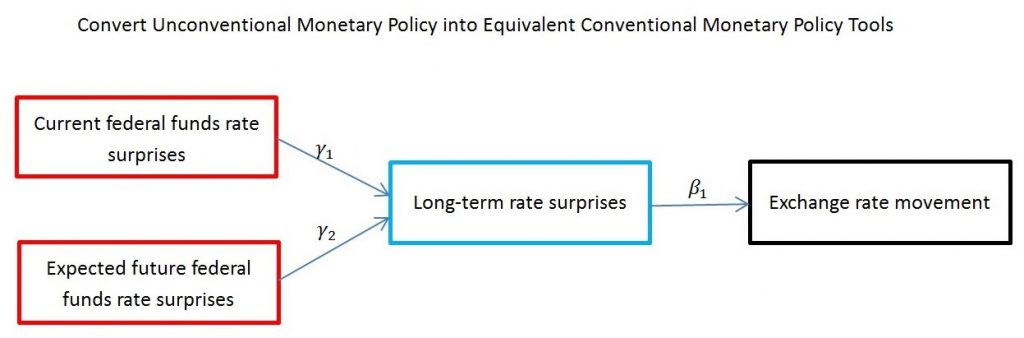

Researchers have long sought to understand how monetary policy announcements affect exchange rates. When the Federal Reserve switched from conventional to unconventional monetary policy measures, a major challenge has been to compare the effect of unconventional monetary policy announcements with that of conventional monetary policy announcements. The pioneering work by Glick and Leduc (2013) converts the unconventional monetary policy surprises into equivalent federal funds rate surprises, thereby enabling the comparison of unconventional and conventional monetary policy effects. They find the unconventional monetary policy has the same “bang” per unit of surprise as the federal funds rate previously had and that the exchange rate channel of monetary policy is still working effectively.

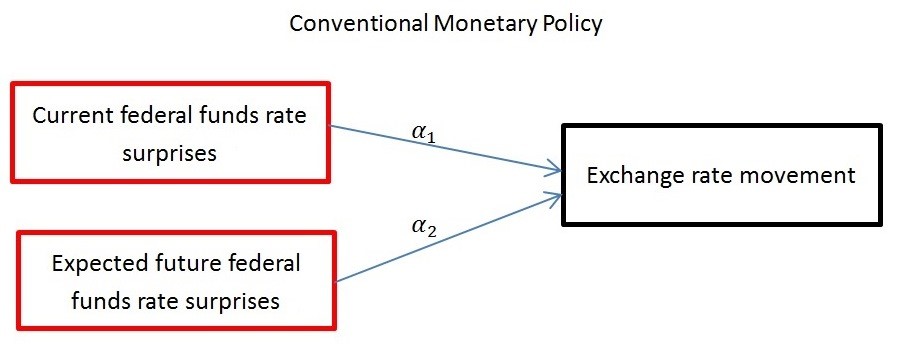

According to Gurkaynak, Sack, and Swanson (2005), the current federal funds rate surprise itself is inadequate to fully capture the effects of U.S. monetary policy announcements on asset prices. In addition to the “current federal funds rate target” factor, a “future path of policy” factor must be added to explain the bond yields and stock prices movements, especially for the longer-term Treasury yields.

Both the current and expected future federal funds rates determine the Treasury bond rates and consequently determine the exchange rate movements. Current federal funds rate surprises capture the “current federal funds rate target” factor, but contain little information about the “future path of policy” factor. Hence if the Fed maintains current federal funds rate, but at the same time provides forward guidance about future federal funds rate, the exchange rate would react to this Fed announcement, but it would be impossible to explain the exchange rate movement using the current federal funds rate surprises.

The FOMC meeting held on June 16-17, 2015 is such an example, where the current federal funds rate surprises cannot be used to explain the exchange rate movement since the current federal funds rate target remains at zero. In the press conference after the meeting, Chair Yellen (2015) said:

The Committee continues to judge that the first increase in the federal funds rate will be appropriate when it has seen further improvement in the labor market and is reasonably confident that inflation will move back to its 2 percent objective over the medium term … the Committee concluded that these conditions have not yet been achieved … the Committee will determine the timing of the initial increase in the federal funds rate on a meeting-by-meeting basis, depending on its assessment of incoming economic information and its implications for the economic outlook.

This speech was widely interpreted (e.g., Hilsenrath (2015), and Ramage (2015)) as a signal that the Fed would raise federal funds rate at a slower pace in coming years than the market projected. The market reacted to this speech instantaneously. The yield on the benchmark 10-year note decreased by 7.7 bps, down from 2.383% before the statement to 2.306% by the end of June 17, 2015. This reaction was spurred not by what the FOMC did, but rather by what it said: indeed, the decision to leave the current federal funds rate target unchanged was completely anticipated by the financial markets, but Yellen’s speech was read by the financial markets as indicating that the FOMC would raise federal funds rate at a slower pace than expected, which led the dollar to depreciate by 78 basis points (bps) against the Euro, from 1.1250USD/EUR by the end of June 16, 2015 to 1.1338USD/EUR by the end of June 17, 2015. Hence, treating the monetary policy action on this date as a zero surprise change in the current federal funds rate would be missing the whole story.

This paper augments Glick and Leduc (2013)’s model with an expected inflation surprise channel, which is used to approximate the expected future federal funds rate surprises (easy to see in an off-the-shelf open-economy New Keynesian model).

(1) For the conventional monetary policy period (before November 2008), the dollar’s value is affected by both the current federal funds rate surprises as well as the expected future federal funds rate surprises.

ExchRate_Mov = α0 + α1FedFund_surp + α2ExpInfl_surp

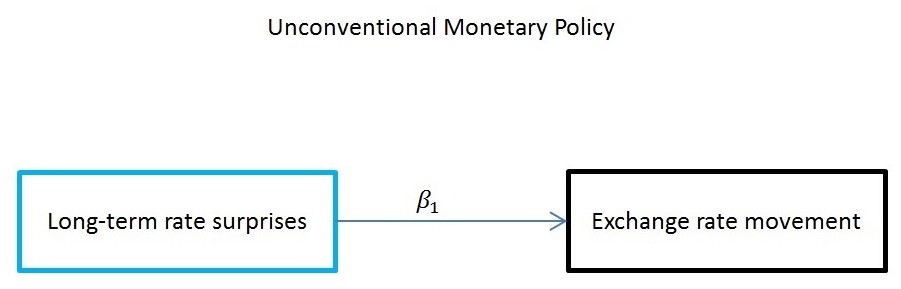

(2) For the unconventional monetary policy period (since November 2008), the dollar’s value is affected by the long-term rate surprises:

ExchRate_Mov = β0 + β1LongRate_surp

(3) I then decompose the long-term rate surprises into current federal funds rate surprises and expected future federal funds rate surprises, the latter of which is well approximated by a linear expression of the expected future inflation surprises. Thus, both conventional and unconventional monetary policy surprises can be contrasted in comparable measures.

LongRate_surp = γ0 + γ1FedFund_surp + γ2ExpInfl_surp

The above steps enable me to compare the unconventional monetary policy effect with the conventional monetary policy effect through two different channels: federal funds rate surprise channel, and expected inflation surprise channel. During the unconventional monetary policy period, a 1 bp long-term rate surprise is equivalent to 1/γ1 bps federal funds rate surprise if the long-term rate surprise solely comes from unexpected current federal funds rate tightening, and is equivalent to 1/γ2 bps unexpected inflation surprise if the long-term rate surprise solely comes from unexpected future federal funds rate tightening. Thus to compare effect of the unconventional monetary policy with that of the conventional monetary policy on the dollar value, I multiply the unconventional policy effect β1 by the adjustment parameter γ1 for the federal funds rate surprise channel, and multiply β1 by the adjustment parameter γ2 for the expected inflation surprise channel. This adjusted unconventional monetary policy effect β1γ1 and β1γ2 can be directly contrasted with the conventional monetary policy effect α1 and α2, where β1γ1 and α1 both measure the effect through federal funds rate surprise channel; and β1γ2 and α2 both measure the effect through expected inflation surprise channel.

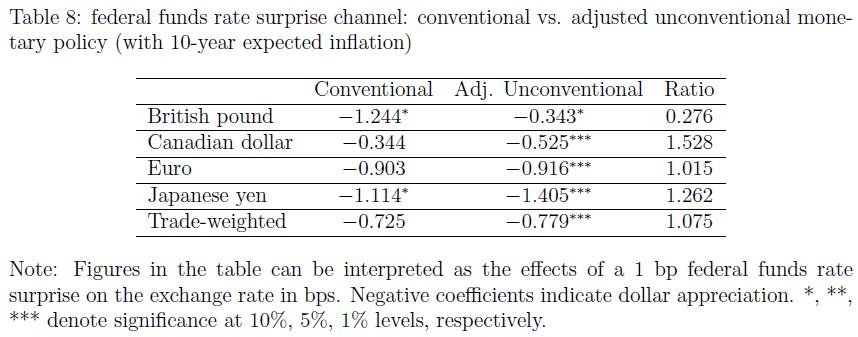

The federal funds rate surprise channel is a revisit of Glick and Leduc (2013) in a more generalized model. Table 8 reports the estimated effects of adjusted unconventional monetary policy through the federal funds rate surprise channel during the unconventional monetary policy period, together with the estimated effects of conventional monetary policy through the federal funds rate surprise channel during the conventional monetary policy period, and the ratio of the two effects. It shows that 1 bp federal funds rate surprise easing leads to a 0.779 bps depreciation in the trade-weighted dollar during the unconventional monetary policy period. This magnitude is comparable to that during conventional monetary policy period’s 0.725 bps, with the ratios of unconventional to conventional period being 1.075. This outcome suggests that during the unconventional monetary policy period, the federal funds rate surprise channel indeed has similar “bang” per unit of surprise as during the conventional monetary policy period.

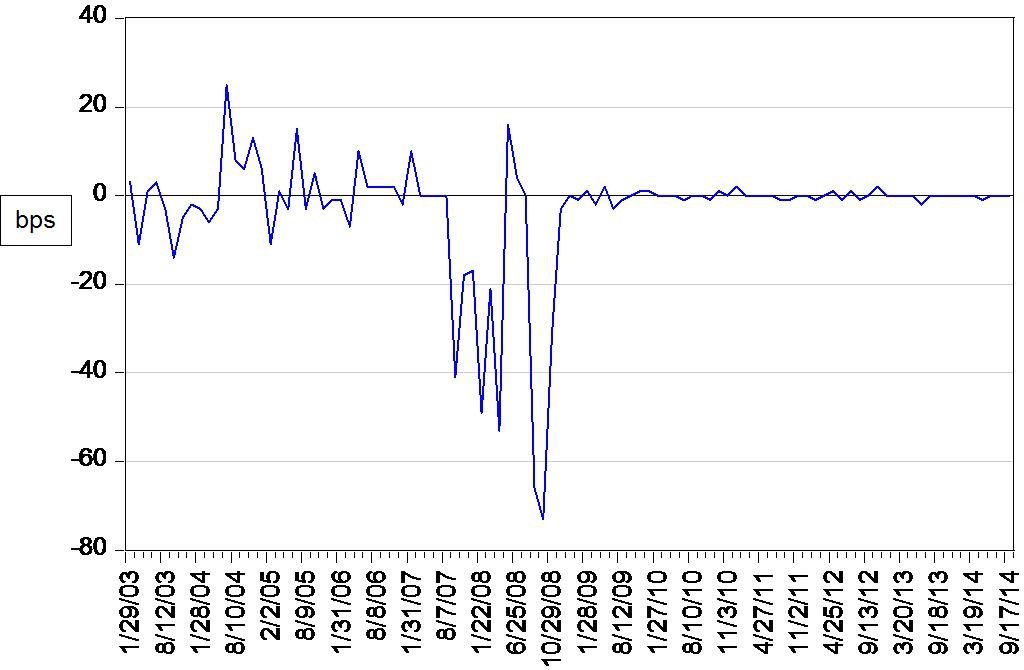

That said, it would be hasty to conclude that the federal funds rate surprise channel is still effective. Given the fact that β1γ1 is approximately the same as α1, the federal funds rate surprise channel is effective only when the Fed is still capable of freely adjusting the federal funds rate. However, during the unconventional monetary policy period, the federal funds rate is stuck at zero, so consequently there is almost no variation in the federal funds rate surprises (see Figure 4). Thus the federal funds rate surprise channel is irrelevant during this period, and the Fed can only affect the economy by manipulating the market’s expectation about future federal funds rate, i.e., via expected inflation surprise channel.

Figure 4: Effective federal funds rate interday changes. Notes: Sample: January 2003 – September 2014, 101 observations.

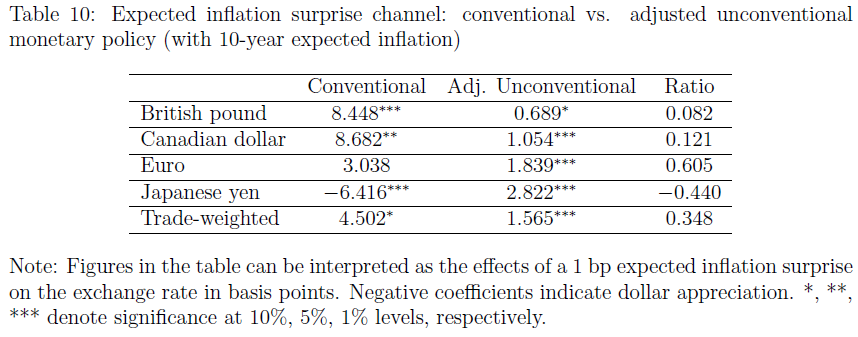

Table 10 reports the estimated effects of adjusted unconventional monetary policy through the expected inflation surprise channel during the unconventional monetary policy period, together with the estimated effects of conventional monetary policy through the expected inflation surprise channel during the conventional monetary policy period, and the ratio of these two effects. It shows that 1 bp expected inflation surprise leads to a 1.565 bps depreciation in the trade-weighted dollar during the unconventional monetary policy period. This magnitude is much smaller than that during conventional monetary policy period’s 4.502 bps, with the ratios of unconventional to conventional period being 0.348. This suggests that during the era of unconventional monetary policy, the expected inflation surprise channel is no longer as effective as during the conventional monetary policy period. That is, the relative importance of expected future federal funds rate in the determination of the exchange rate has weakened dramatically compared to the pre-crisis period.

This post written by Yi Zhang.

That’s all nice and tidy, Mr. Zhang.

But the real drama is going on elsewhere:

https://theintercept.com/2016/03/02/larry-fink-and-his-blackrock-team-poised-to-take-over-hillary-clintons-treasury-department/

That is to say: after HRC becomes President, and the MSM is already in high gear for that, we will see Fink take over the Treasury. And then: ‘good night’ to all democratic principles.

Does the Federal Reserve risk losing its effectiveness on forward guidance due to revisions? With forward guidance being a new tool and not having historical data, will markets later see this communication as unreliable? It seems to me that perhaps a better tool would be to project forward guidances according to certain economic scenarios. With a base-case and than perhaps an overheating, slower growth, recession case.