Fixed nonresidential investment is rising at a rapid clip. However, there are some nuances to the headline story.

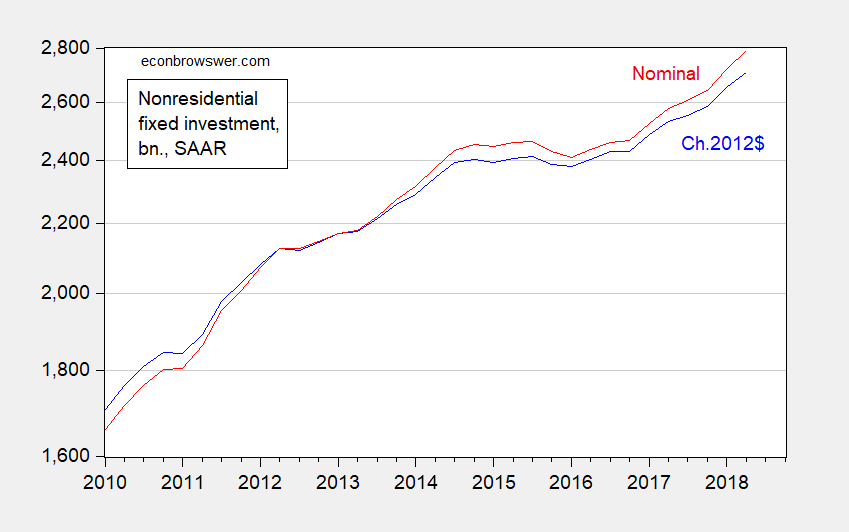

Figure 1: Nonresidential fixed investment, in billions of Ch.2012$ (blue), and in billions of dollars (red), both SAAR, both on log-scale. Source: BEA, 2018Q2 2nd release.

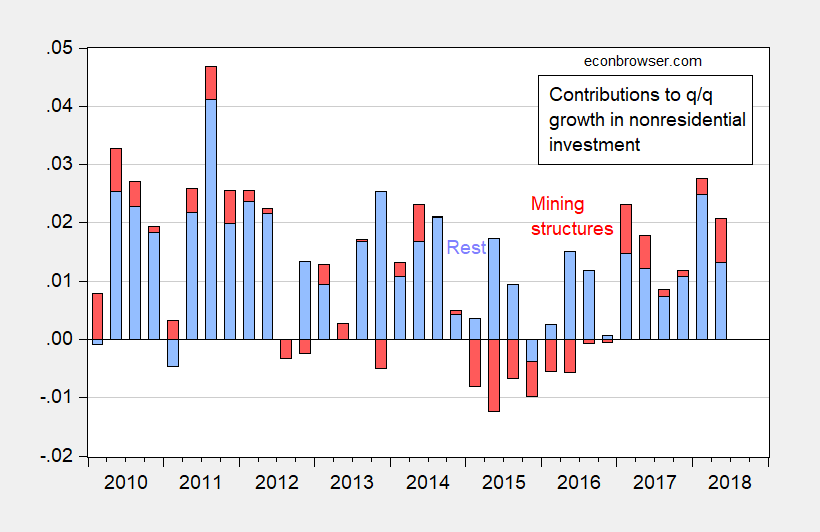

Some sizable portion of recent investment is associated with the mining/drilling/fracking phenomenon.

Figure 2: Contributions to overall nonresidential fixed investment growth of structures investment in mining (red), and all else (blue). Source: BEA, 2018Q2 2nd release, and author’s calculations.

For the moment, investment looks like it should be sustained. However, should oil prices decline, or the spigot of cash diminish (see McLean/NYT today), then the support coming from this sector might disappear. (This article discusses light tight oil (LTO) sector cash flow, financing, and prospective capital investment.)

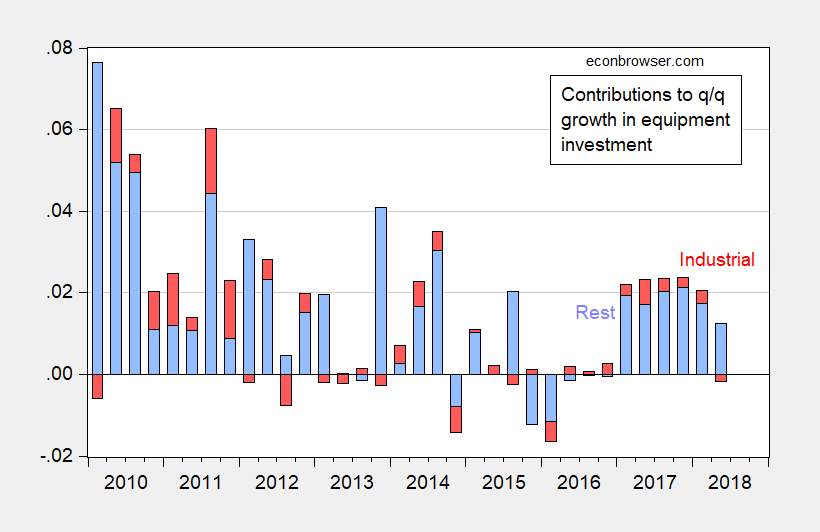

In addition, investment in equipment, while rising overall, is declining in the industrial sector.

Figure 3: Contributions to overall equipment investment growth of industrial equipment investment (red), and all else (blue). Source: BEA, 2018Q2 2nd release, and author’s calculations.

Right now, increased investment demand coming from the accelerator is more than offsetting the drag coming from higher policy uncertainty. As the effects of the tax cuts wear off, we should expect the balance to shift.

“Some sizable portion of recent investment is associated with the mining/drilling/fracking phenomenon.”

The link that analyzing the fracking sector is a must read!

Menzie,

Are you still experiencing a depreciation boom?

Andy Hall’s and my response to the McLean piece can be found here:

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2018/9/2/americas-energy-boom-is-not-shaky

US shales represent 63% of total oil supply growth since 2005, with Canada 77%. OPEC has contributed 20%, which has been just enough to offset declines from countries where production is falling.

Add Russia and Brazil — both about 11% of supply growth over the period — to the mix, and that’s all folks.

If oil prices decline, it will be for one of two reasons: 1) a global recession, or 2) extra productivity from shales which overruns demand. A global recession is most likely to be preceded by high oil prices, so that helps shales. And if shales overrun demand, then that attests to shales’ enormous productivity. Both of these narratives are supportive of the shale story.

I thought this was the news today.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/sep/03/south-koreas-fertility-rate-set-to-hit-record-low

Makes me think of this:

http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/22514/1/2308Ramadams.pdf

Menzie, your IEA reference, https://www.iea.org/newsroom/news/2018/july/investment-analysis-the-journey-of-us-light-tight-oil-production-towards-a-finan.html

says this: “2018: Profitability at last?

Current trends suggest that the shale industry as a whole may finally turn a profit in 2018, although downside risks remain. …”

Maybe, if the price of oil stabilizes at this level for a period, the technological economies starting the fracking industry may result in an extended period of profitability. Probably too many ifs to make any certain predictions.

Maybe Steven Kopits has an opinion.

Motley Fool often has very useful information such as this:

https://www.fool.com/investing/2016/07/16/which-companies-are-the-biggest-shale-players-in-t.aspx

“What are the largest shale-focused companies? EOG Resources (NYSE:EOG) has quickly become one of the nation’s leading oil producers thanks to its prime positions in the Bakken, Eagle Ford, and Permian formations. In fact, according to the Railroad Commission of Texas (which, by a quirk of political history, regulates natural resources and the environment), EOG Resources was the largest oil producer in 2016, averaging 248,984 barrels of oil per day — 9.3% of Texas’ output. EOG Resources also ranked as Texas’ eighth-largest gas producer, accounting for 2.8% of the gas extracted.”

EOG lists around $26 billion in operating assets at book value. On $11.2 billion in revenue, it booked over $926 million in operating profits and its interest expenses were only $274 million per its 10-K filing.

Its stock price is doing well putting the market value of its equity at $68.5 billion well about the book value of $16.3 billion:

https://finance.yahoo.com/quote/EOG/balance-sheet?p=EOG

The market is at least optimistic about this company’s future.

The total and manufacturing capacity utilization rates remain low. Of course, there are upgrades, but expansion may be slow. However, big tech seems to be in a capital and R&D spending spree:

“Aggregate spending for 2018 among the 10 largest tech companies is approaching $100 billion each for capital expenditures and R&D…Capital expenditure commitments and R&D outlays are seen rising 47% and 24%, respectively, this year.”

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.thestreet.com/amp/technology/10-big-tech-companies-spending-100-billion-in-2018-to-dominate-even-more-14596963

PeakTrader: Do you ever look at data before you post? Capacity utilization in mfg (NAICS) is 76.4 in July. Prior peak in April 2007 was 79.4.

Menzie Chinn, it looks like there’s a lot of excess capacity:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MCUMFN

Due to structural changes the trend CU is declining in advanced economies. For this reason excess capacity should not be judged based on peaks achieved 30y ago. Fred has some nice articles on this phenomenon.

https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/some-characteristics-of-the-decline-in-manufacturing-capacity-utilization-20180301.html

Nice! Of course I have my doubts whether PeakTrader will actually read this material.

Here’s a link on capacity utilization:

https://fredblog.stlouisfed.org/2018/04/trends-in-capacity-utilization-around-the-world/

https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/some-characteristics-of-the-decline-in-manufacturing-capacity-utilization-20180301.htm

March 01, 2018

Some Characteristics of the Decline in Manufacturing Capacity Utilization

Justin Pierce and Emily Wisniewski

Background

Capacity utilization, defined as the ratio of actual production to maximum sustainable production, has long been viewed as an important measure of slack in the economy, and the Federal Reserve Board has published capacity utilization rates for the manufacturing sector since the 1960s. The G.17 Statistical Release on Industrial Production and Capacity Utilization reports that manufacturing capacity utilization was 76.4 percent in December 2017, indicating that more than eight years into the current expansion, capacity utilization remains 2 percentage points below its long-run (1972–2016) average. This paltry recovery in operating rates continues a decades-long downward trend in which capacity utilization has rarely re-attained its previous peak following a recession (Figure 1).

The resulting downward trend in manufacturing capacity utilization raises several important questions. Does the overall manufacturing capacity utilization rate overstate the level of slack due to changes in output among industries within the sector? Are utilization rates suppressed by labor shortages, skill mismatch, or changes in the use of labor? Are the declines concentrated in a small group of industries or widespread? Are the declining utilization rates observed in the aggregate also occurring within long-lived establishments?

In this note, we provide several observations regarding trends in manufacturing capacity utilization rates using data from the Federal Reserve Board and the Census Bureau. The note does not aim to consider all potential explanations for the decline in utilization rates, and indeed we do not find a single root cause of the decline. We do, however, attempt to narrow the scope of potential explanations and contribute contemporary data to the existing commentary.

US looks dreadful by international comparison.

Sorry to repeat myself but is the depreciation boom continuing or ont. I am interested if NET investment is making a move at all??

And, perhaps, the capacity utilization rate in the 2000s would’ve been higher, if we didn’t massively offshore low-end manufacturing, which likely slowed substantially in the 2010s.

Gee – have you ever thought that the natural rate of capacity utilization may have changed over the past 40 years? Guess not.

I found one claim from this article interesting but maybe outdated:

https://www.iea.org/newsroom/news/2018/july/investment-analysis-the-journey-of-us-light-tight-oil-production-towards-a-finan.html

“Throughout this phase, companies were forced to rely extensively on external sources of financing, predominantly debt and receipts from the sale of non-core assets, in order to finance their operations. In addition to issuing bonds, companies benefited from the reserve base lending structure – a bank-syndicated revolving credit facility secured by the companies’ oil and gas reserves as collateral. This structure was used heavily by small and medium-sized companies with non-investment credit rating that did not have as easy access to the corporate bond market…The fall in prices also changed the way the shale industry was financed. Debt finance dried up as banks were unwilling to lend during a period of market turmoil, with bond yield spreads widening to over 1 000 basis points and the credit rating of the majority of companies being downgraded.”

These kind of high interest rate loans strike me as Trumpian financing. But what about the two main players noted in the Motley Fool article? EOG Resources and Pioneer Natural Resources are both profitable and currently the extent of their debt financing is more modest. You can check at http://www.sec.gov for the interest rates on their corporate bond offerings, which are not that high. It seems their credit ratings have been upgrade to investment grade as in BBB or something near that. Of course, this is a period when oil prices are high.

“PeakTraderSeptember 4, 2018 at 8:03 am

Here’s a link on capacity utilization:”

International Comparisons of Capacity Utilization? Seriously? Vasja wants you to read “Some Characteristics of the Decline in Manufacturing Capacity Utilization” by Justin Pierce and Emily Wisniewski which is an excellent discussion with U.S. data going further back in time than what FRED provides. Alas – his link has an extra letter at the end so it does not work but I put up a link that does work.

Like I said – I doubt who have bothered to read what Vasja alerted us to. Pity!

“Steven Kopits

September 4, 2018 at 11:36 am

US looks dreadful by international comparison.”

Oh brother! Maybe we need a primer on why international comparisons like these can be misleading!

All the Central Banks have 10+T on balance sheet. The Fed still holds 1.7T on Mortgage-Backed Assets, enough to sink an industry and a nation. The Tech golden boys are born in this way…

The way out (or not) is to consolidate Equity, let Equity drive Growth.

There’s likely a relationship between U.S. capacity utilization in manufacturing and globalization.

When the U.S. offshored older industries, particularly in 1990 to 2007, manufacturing productivity averaged over 4% a year. Resources were shifted from older manufacturing industries into emerging industries, in the Information and Biotech Revolutions, and high-end manufacturing, creating unutilized manufacturing capacity.

Manufacturing wages are above average. However, the shift in resources created higher paying jobs (in emerging industries and high-end manufacturing) and lower paying jobs (e.g. retail and related industries). It resulted in greater income inequality, but stronger GDP growth.

“There’s likely a relationship between U.S. capacity utilization in manufacturing and globalization.”

OK Peaky – now that you are arguing against yourself again, why not read that piece Vasja and I have tried to get you to check out?

Pgl, the article you cited supports what I said, including continuing establishments have a lower utilization rate and a labor shortage in high-end manufacturing. You’re the one arguing with nothing, except nonsense.

Oh please. You start with a premise that there is some natural rate of the capacity utilization rate that is unchanged over 40 years and should be the same internationally. Both of which are absurd. Well at least you read the materials which show the flaw in your original thinking. When you finally get a coherent and consistent grasp of reality – do report back.

Pgl, changing the subject doesn’t support your nonsense.

There are factors that explain why capacity utilization rates change.

Germany, for example, has a much higher capacity utilization rate in manufacturing and a larger proportion of its economy is in manufacturing than the U.S., which is inflationary and reflect high wages. Yet, its GDP is over $10,000 a year lower with slower economic growth than the U.S..

Of course, the U.S. leads the rest of the world combined in the Information and Biotech Revolutions, in both revenue and profit, while wages in those new industries are higher. Yet, lots of Americans are working for only $9 to $11 an hour with little or no benefits.