Today we are fortunate to be able to present a guest contribution written by Mark Copelovitch (University of Wisconsin – Madison) and David Singer (MIT).

“The peculiar essence of our financial system is an unprecedented trust between man and man; and when that trust is much weakened by hidden causes, a small accident may greatly hurt it, and a great accident for a moment may almost destroy it.” –Walter Bagehot (1873), Lombard Street: A Description of the Money Market, pp.158-9.

Why do banking crises occur? In our new book, Banks on the Brink: Global Capital Securities Markets, and the Political Roots of Financial Crises, we seek to understand why some countries are more prone to banking crises than other countries or at different times.

At the simplest level, banks collapse because customers lose trust in them. Trust is ubiquitous in the financial system. Banks trust that customers will repay their loans. Depositors trust that banks will manage their money carefully. And banks trust other banks to provide liquidity and to remain standing day after day. But as Walter Bagehot noted in his famed account of London’s 1866 financial panic, trust in the financial system can erode from “hidden causes.” When trust is weakened, even seemingly small accidents—like the collapse of London bank Overend, Gurney, and Company, which triggered the 1866 panic—can cause systemic financial crises.

The details of individual banking crises vary, but rarely does trust in the banking system evaporate without due cause. In the Panic of 1907, banks collapsed because they were complicit in speculation and market manipulation that led to massive financial losses. During the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, the trigger for the collapse of Thai banks was speculative lending to real estate developers, which led to a boom and bust in the real estate market. And in 2008, after a decade of easy mortgages to borrowers with shaky credit histories and a growing bubble in the real estate market, investors grew fearful that banks and holders of mortgage-backed securities might never get their money back.

Our book highlights two key triggers of banking crises. The first, levels of foreign capital inflows, sets the stage for potential distortions in the financial system. Large capital inflows have been found to be a consistent correlate of banking crises. Indeed, many scholars believe that the malignancy of global capital flows is the most likely culprit behind banking crises. In Lost Decades, their analysis of the Great Recession, Chinn and Frieden (2011) point to the enduring prevalence of the capital flow cycle, in which “capital floods into a country, stimulates an economic boom, encourages high-flying financial and other activities, and eventually culminates in a crash.” They note that many previous crises fit this pattern, including the Mexican and Asian crises in the 1990s, and dozens of others. Reinhart and Rogoff, in this This Time is Different (2009), suggest that the pattern has deep historical roots. One of their key findings, backed by data covering 800 years of financial crises, is that large current account deficits, asset price bubbles, and excessive sovereign borrowing are common precursors of crises across space and time. Moreover, bank failures were relatively rare during the Bretton Woods monetary system from the end of World War II to the early 1970s, when governments enacted strict controls on capital movements (Helleiner 1994). This overall finding—that foreign capital opens up a Pandora’s Box of financial distortions—now has the status of conventional wisdom in academic and policy circles.

The potential dangers of capital inflows are real. But existing research has failed to emphasize that foreign capital is not always destabilizing for the banking system. For every instance of a banking crisis preceded by large capital inflows, there are countless examples where inflows are harmlessly—and even productively— channeled throughout the national financial system. For example, while the U.K. and the U.S. both experienced large current account deficits in the years preceding the Great Recession. Australia and New Zealand also experienced substantial current account deficits, but their banking systems escaped relatively unscathed.

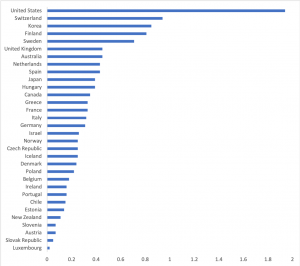

Why do capital inflows lead to banking crises in some cases but not in others? To explain this, we focus on a second variable: national financial market structure. We argue that the substantial variation in the relative prominence of banks versus securities markets (Figure 1) determines whether capital inflows are channeled safely and productively through the national economy, or whether they instead cause banks to take on excessive risks and increase the likelihood of a financial crisis. Banks often sit alongside other financial institutions, including stock and bond markets, which provide alternative sources of financing for borrowers and alternative investments for savers. When banks are conservative because of the relative absence of competition for financial intermediation, foreign capital can be safely channeled into the system without causing bank instability. On the other hand, when banks sit alongside viable securities markets, capital inflows exacerbate banks’ risk taking and increase the probability of a crisis.

Figure 1: Market/bank ratio, OECD countries, average, 1990-2011

Source: World Bank Global Financial Development Database, calculated as the ratio of stock market trading volume to total bank lending

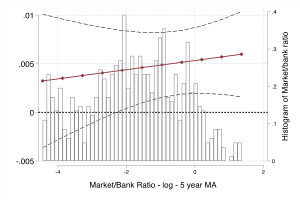

To test our argument, we analyze data from the 1970s through the early 21st century for most of the world’s developed economies. Figure 2 illustrates the core result of our statistical analysis: capital inflows are only correlated with banking crises under certain conditions – namely, when they flow into a financial system in which commercial banks compete alongside large and highly-developed securities markets.

Figure 2: Average Conditional Marginal Effect of Gross Portfolio Capital Inflows on Probability of a Banking Crisis, by Market/Bank Ratio (World Bank banking crisis classification), 1970-2011

Coefficient on change in gross portfolio inflows (% of trend GDP, 5-year moving average)

In this book, we not only explore the determinants of banking crises, we also explore how capital inflows and financial market structure interact to affect banks’ risk taking. The conventional wisdom linking capital inflows to crises emphasizes distortions in the allocation of capital as it is channeled through banks and other intermediaries (Portes 2009). The question is precisely how this plays out and which distortions are most salient. Some scholars find a clear link between capital inflows and the volume of credit. For example, Schularick et. al. (2012), in their groundbreaking work on the long-term patterns of financial instability in industrialized countries, find that 1) domestic credit growth is the single most important determinant of banking crises; and 2) capital inflows, as measured by current account deficits, go hand-in-hand with credit booms, especially in the post-Bretton Woods era. In contrast, other scholars, such as Amri et. al. (2016), find only a weak relationship between capital inflows and domestic credit growth and notes that this connection is diminishing over the last two decades.

If capital inflows lead to banking crises by triggering changes in the volume of domestic lending, then we should find a similar conditional, interactive relationship between capital inflows, financial market structure, and credit growth as we did with banking crises. However, we find no such relationship – either unconditionally or conditionally – between capital inflows and the growth rate of domestic bank credit. While capital inflows are conditionally correlated with banking crises, the relationship does not appear to operate through a simple increase in the volume of bank loans. Rather, credit booms appear to be a separate channel of financial instability from the one we identify in our analysis.

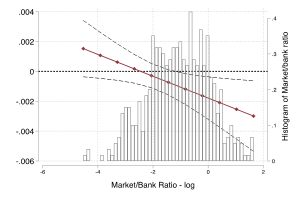

In contrast, we do find evidence that capital inflows influence the propensity of banks to take on greater risk, through a reduction in capital cushions and/or the assumption of greater insolvency risk – and that this varies depending on a country’s domestic financial market structure. In other words, capital inflows – in financial systems where banks complete alongside large securities markets – affect the quality of bank lending and the composition of bank balance sheets.

Figure 3 illustrates this second core result. It shows the conditional relationship between capital inflows, market structure, and national level averages of Tier 1 commercial bank capital. These results strongly suggest that capital inflows trigger banking crises not because they cause credit booms (surges in the volume of bank lending), but because they lead banks to reduce their capital holdings and lend to more risky customers. This decline in the quality of banks’ loan portfolios, rather than an increase in the number and amount of loans, appears to be the “smoking gun” linking capital inflows to banking crises in industrialized countries.

Figure 3: Average Conditional Marginal Effect of Gross Portfolio Inflows (% trend GDP) on Tier 1 Commercial Bank Capital Ratio, by Market/Bank Ratio

Coefficient on change in gross portfolio inflows (% of trend GDP)

The political roots of financial market structure

While our statistical analysis shows that financial market structure mediates the effects of foreign capital inflows, it cannot explain how such variation in market structure developed in the first place. To resolve this puzzle, we turn to historical analysis, zeroing in on the political decisions that shape the structure of financial markets that make certain countries especially vulnerable to banking crises. Through detailed historical case studies of Canada and Germany, Banks on the Brink shows how seemingly innocuous political decisions about financial rules can accumulate over decades and solidify a country’s financial market structure for generations.

In our case study of Canada, we show that the country’s remarkable history of bank stability has been attributable in part to its equally remarkable fragmented and underdeveloped stock markets. The Canadian Constitution granted the national government the sole authority to regulate the banking industry, but authority over stock markets was relegated to the provinces. During the economic crisis of the early 1930s, while the U.S. government seized the opportunity to create a national securities regulator and to minimize the role of state regulatory agencies, Canada made few changes to its regulatory system. The government took no steps to create a national regulator, instead reaffirming the authority of the provinces to supervise their stock exchanges in accordance with their particular needs. To this day, Canada is the only industrialized country without a national securities regulator. We argue that the country’s underdeveloped securities markets have had a salutary effect on its banks, which have been successful in channeling foreign capital to borrowers over the last four decades without taking on undue risk.

Like Canada, Germany has a long history of bank stability, but it has recently taken a dangerous turn. Our case study highlights how policy decisions in the aftermath of two major financial crises—the Panic of 1873 and the crisis of 1931—arrested the development of German securities markets and solidified a heavily bank-centric financial system. Interest-group and party politics, rising nationalism and anti-Semitism in the late 19th century, and the Nazis’ ascendance to power in the 1930s all conspired to hobble the development of German stock markets prior to World War II, allowing banks to engage in long-term conservative lending with “patient capital” throughout the postwar era until the 1980s. In recent years, however, financial competitors from within and outside Germany have prompted the large German banks to seek alternative sources of revenue. Deutsche Bank, Commerzbank, and other large banks have become champions of Finanzplatz Deutschland, a single large securities market designed to compete with New York and London. As this market has developed, the conservative bias of German banks has eroded, and many required emergency bailouts in the early 21st century.

Key implications

Banks on the Brink shows that politics is the root cause of financial crises, but not in the way that many observers might imagine. Bankers themselves have political preferences and may express them publicly, and some banks lobby for favorable public policies and donate to political campaigns and political action committees. But at a deeper level, banks are embedded in financial markets, which themselves reflect an accumulation of government choices. Banks today operate in an environment shaped by these political choices, some of which make banks more resilient, others of which make them more prone to crisis. This variation, across space and time, explains why some countries find themselves more vulnerable to banking crises and the dangers of foreign capital inflows than others.

These findings have key policy implications for how to minimize the risk of banking crises in the U.S. and elsewhere. In light of the slow-moving nature of financial market structure, any policy proposal to fundamentally alter the shape and depth of financial markets will likely be dead on arrival. Proposals to re-introduce Glass-Steagall-type regulations which separate commercial and investment banking might be episodically popular in countries like the U.S., but as our evidence suggests, they would fail to address the underlying reasons for banks’ excessive risk taking. We also argue against capital controls. Instead, we suggest that regulators should focus their efforts are tightening bank capital requirements, especially in financial systems with prominent or growing securities markets. Governments are unlikely to be able or willing to fundamentally alter the structure of domestic financial markets in the short- or medium-term. But they can ensure that financial institutions act more prudently, especially when foreign capital inflows flood into the country and the temptation for banks to engage in more risky behavior is greatest.

This post written by Mark Copelovitch and David Singer.

So do these guys think the Bael III limits recently adopted for the largest US banks will suffice? Or do we need to spread those to all US banks or even go for tighter capital requirements in a Basel IV?

I hope the authors Copelovitch and Singer have read your very deep thoughts on this matter Junior. It’s certain to be an “eye-opening” view and revelatory to their own research on the matter. Too bad they couldn’t put this as a footnote somewhere in the book before it left the publisher.

https://econbrowser.com/archives/2019/11/recession-probabilities-september-october-2020#comment-231991

I do not. I think Martin Wolf and Admati/Hellweg are still correct in the need for substantially more capital: https://www.ft.com/content/9dd43a1a-9d49-11e7-8cd4-932067fbf946

Thanks for your reply, Mark. That was what I expected.

I guess you should be filled in on what is going on with Moses Herzoghere and why he is linking to some comments I made back in November. So this was all about instabilities that erupted in the repo markets in September, with ovrrnight rates briefly hitting 10%. A lot of commentary identified this as a liquidity problem tied to a combination of needs tied to the end of third quarter coming up with the fact that larger US banks were now facing the higher Basel III capital requitements. Most of us think that the Fed handled the situation well by becoming reengaged in providing liquidity to the repo market and halting the drawdown of Fed balances (indeed reversing action to start reaccumulating them again gradually).

At the time Moses had a different view that the September instabilities in the repo market had nothing to do with end-of-quareter liquidity demands, and indeed was not a liquidity problem at all. For him the problem was due to a bunch of bad loans the banks had made because their capital requirements were too low, although, of course, he never presented any evidence of any noticeable increase in loan defaults going on last year. I happened to agree that there was good reason for there to be higher capital requirements, but that indeed this made life more difficult for those large banks at certain times when there needed more liquidity, with thus a need for the Fed to step in and help. As you can see from the link I was fine with the Fed intervening to provide more liquidity, and indeed accruately prediicted that they would continue to do so as they have beyond the January date they said they would stop doing it.

Of course more recently several weeks ago we had the episode when people were having trouble selling 30-year Treasury bonds, with the repo markets again acting up. As it was, the Fed responded to that by pumping in $1.5 trillion to help smooth things and assure sufficient liquidity. When I mentioned that here (after having posted on it on Econospeak), Moses popped up to repeat these arguments ha made in the fall, although now arguing that what was going on was rising defaults on corporate bonds, not, forfend, liquidity problems for banks as I (and many others) had argued in the fall. I noted this time that indeed we may be facing corporate bond defaults as the economy plummets into deep recession, but that was not what was triggering the problems in the repo markets to which the Fed responded with its massive injeciton of liquidity.

BTW, if you are curious why he refers to me as “junior,” something he likes to do here a lot when he thinks he is proving a point (usually it is “Barkley Junior”), this is because indeed I am a junior, being the son of the late J. Barkley Rosser (Sr.), known for work in logic, rocket ballistics, and various other ares of mathematics and computer science. As someone at UW-Madison with Menzie (where I got my PhD in econ), you should probably know that my late father was the Director of the Army Mathematics Research Center when it was blown up by the New Year’s Gang nearly half a century ago on Aug.24, 1970.

Anyway, I can unseerstand that you might prefer to stay out of this basically silly contretemps. Moses does not take well to having a bunch of people tell him he is wrong about something (as happened last fall), especially when one of them is me, and tends to drag these matters up at various times liike a dog pulling out a way-overly-chewed-on bone. Of course, if you happen to think he is right about all this, I am sure he would love to have that confirmed by you. He is quite obsessed for reasons not really clear to me in finding “junior” me in error whenever he can.

Thanks agaiin for your post and reply to my quesion, and congratulations on your book.

Oh, a caveat. The New Year’s Gang were trying to blow up the AMRC, then located in Sterling Halll, but instead hit the physics department, killing a grad student (Robert Fassnacht) and injuring several others. They had often missed their targets during their bomb attacks earlier in the year, being essentially The Gang That Could Not Bomb Straight.

Thanks for the paper links. I think libraries (at least over the next 6 months) are going to be thinking more and more about how hardcopy materials can cause a problem with the COVID-19. This makes me incredibly sad if I fixate on it long enough, as I treasure getting hardcopy books from my public library. However I will still put in an order/request for my public library to put this Copelovitch/Singer book in their inventory on their shelves. They have been exceedingly good about getting new books I ask for up to the point the virus became an, uh, “exogenous” threat. I think over time libraries will become more flexible on the exchange of hardcopy materials once again as the COVID-19 threat subsides (I am looking many months into the future here people). Cross your fingers.

“I think libraries (at least over the next 6 months) are going to be thinking more and more about how hardcopy materials can cause a problem with the COVID-19.”

The virus is dead after a few hours on all surfaces. The study was a technical study with limited reelvance for real life, typical issue of press reporting scientific results without undertsanding them.

(Drosten explains the issues very well. :-))

I’m watching the first (and only) season of “Swamp Thing” right now. There seems to be many comparison to the creature and some kind of mutation or virus. I don’t know if this is the most mentally healthy thing to watch right now in congruency with the current news events. Of course, this is like 1 of like 8 fictional TV series I actually like in the last 10 years and they cancelled the series for seemingly no reason. They must have heard it was something I enjoyed.

There is some cursing and vulgarity in this, but it’s not gratuitous cursing, overall it’s educational and useful to people:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4J0d59dd-qM

For non-finance folks such as myself, I found “The Bankers’ New Clothes: What’s Wrong with Banking and What to Do about It” by Anat Admadi and Martin Hellwig easy to understand and well written. Admati is on the faculty at Stanford and Hellwig is director of the Max Planck Institute for Research on Collective Goods.

It’s a great book, I have it in my closet somewhere (shamefully, not fully read) and for the record, I am an Anat Admati fanboy. No big deal, but if you’re doing a web search her last name just had the one “d” before the “t”.

Menzie wrote a paper or two with Peter Navarro. I wonder if he can explain this interview:

https://talkingpointsmemo.com/news/brianna-keilar-peter-navarro-interview-waste-time

CNN host Brianna Keilar’s interview with White House trade adviser Peter Navarro got heated on Thursday when she attempted to prod him to explain how the Trump administration was addressing the hospital ventilator shortages as the COVID-19 outbreak escalates. “You’re wasting everyone’s time with this,” Keilar said when Navarro tried to invoke President Donald Trump’s talking point of blaming the Obama administration for Trump’s own blundering response to the coronavirus. “It’s 2020. The President was elected in 2016,” the CNN host continued. “Can you get to a million ventilators?” Navarro downplayed the number of ventilators needed and accused Keilar of “frightening America with that kind of stuff.” “Peter, if you think that speaking in facts and truth is frightening to people, you have a problem,” she replied, pointing to the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s estimate that medical professionals will require approximately 960,000 ventilators to treat coronavirus patients under critical condition. “Why do you keep shouting in my ear? I don’t understand,” Navarro complained. “Well, because you’re not answering my question,” Keilar shot back. The White House official then pontificated about how the nation needs to “band together and work with this in a unified way” while claiming that CNN was sensationalizing the coronavirus to “stir people up.” By that point, the CNN anchor had run out of patience: “Peter, that is just a waste of time to say that.”

Listen to the interview as it truly was that bad!

@ pgl

Menzie would say (and he’d right) “You can’t blame me if I co-wrote a book “X” decades ago with a guy who later turned into an ideological nut job”. But you know, unless he’s hit the news, I don’t bring Ron Vara up, because I know it would annoy the hell out of me if others brought that up, so I assume he feels the same.

*and he’d be right

Agreeing with you on this matter, Moses. Once upon a time Navarro was a not entirely unreasonable economist, with his Harvard PhD, and wrote quiite few respectable paper. I think that one with Menzie was near the end of that period. Then he just went off the rails to become this total embarrassment to the entire US economiocs profession.

Menzie is certainly not responsible for that and does not need to explain anything Navarro does now, especially something as just plain awful as this.

navarro comes across as the rigid old white guy who expects you to give him his due, because he is peter navarro. the interview was an embarrassment, and is striking in the entitlement mentality navarro exhibits. i just find it fascinating that the trump administration can be in office for over THREE years and yet still blame EVERYTHING on previous administrations. what the hell has the administration been doing for the past three years, besides worrying about trump property income streams? they accept NO RESPONSIBILITY whatsoever for their actions in office-or inactions as the current situation indicates. the big problem with putting big business types in public office is they have very little concern for CONTINGENCIES, because to them these are wasted costs. but successful public policy is built upon contingencies, something nobody in the white house seems to understand anymore. spending time and money to prepare for a risky outcome that never occurs is NOT a waste of time and money for a government operation. your job is to protect against those risky outcomes. hopefully trump has not pushed this mentality out of the military as well.