Today, we are fortunate to present a guest contribution written by Marcelo Bianconi (Tufts), Federico Esposito (Tufts), and Marco Sammon (Northwestern).

The recent threat of a trade war between US and China has brought trade policy uncertainty (henceforth TPU) to the forefront of the economic and policy debate. A substantive empirical literature has analyzed the effects of TPU on employment, international trade, investment, and welfare. While this literature has focused on the impact of TPU on economic outcomes, it has remained silent on its effect on asset prices. Given the relevance that stock prices have for firms’ investment decisions, household wealth, and employment, studying how financial markets respond to TPU deserves further scrutiny.

In new research (Bianconi, Esposito and Sammon 2020), we document that TPU is a systematic risk factor priced by asset markets.

Since the fundamental work of Bernanke (1993), it is well-known that macro-level economic uncertainty can decrease investment. Davis (2018) has clearly highlighted the negative investment effects of the current administration’s recent trade-policy uncertainty. Academic research on the effect of TPU on economic outcomes has been vibrant, e.g. Handley and Limão (2015) and Pierce and Schott (2016), among many others.

Under the current COVID-19 pandemic, the impact on asset prices has been dramatic, e.g. Baker et al. (2020). There is substantial uncertainty about when the economy will re-open and how trade relations will change as the economy returns to normal. Uncertainty about future tariffs could affect investors’ expectations of future performance and risk. These changes in risk affect firms’ stock returns, which are an important determinant of household wealth, firms’ value and investment decisions, e.g. Davis et al. (2006). We find robust empirical evidence that TPU affects both the mean and volatility of U.S firms’ stock returns, as investors demand a 6% risk premium for holding stocks exposed to possible policy changes. In short, investors demand compensation for the risk associated with future policy changes.

Our empirical results are based on the uncertainty arising from annual votes by Congress to revoke China’s ‘‘Most Favored Nation’’ (MFN) status between 1990 and 2001. Starting in 1980, U.S. imports from China were subject to the relatively low Normal Trade Relations (NTR), or equivalently MFN tariff rates reserved for WTO members, even though China was not a member of the WTO. This required annual renewals by Congress, were essentially automatic until the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989. Starting in 1990, NTR renewal in Congress became more politically contentious, with the House passing resolutions against Chinese MFN renewal in 1991 and 1992. Had NTR status been revoked, tariffs would have reverted to the higher non-NTR rates, established under the Smoot Hawley Tariff Act of 1930. The uncertainty about substantial U.S. import tariff increases on Chinese goods ended in 2001, when the US granted China ‘‘Permanent Normal Trade Relations’’ (PNTR), which eliminated the need for annual votes on MFN renewal.

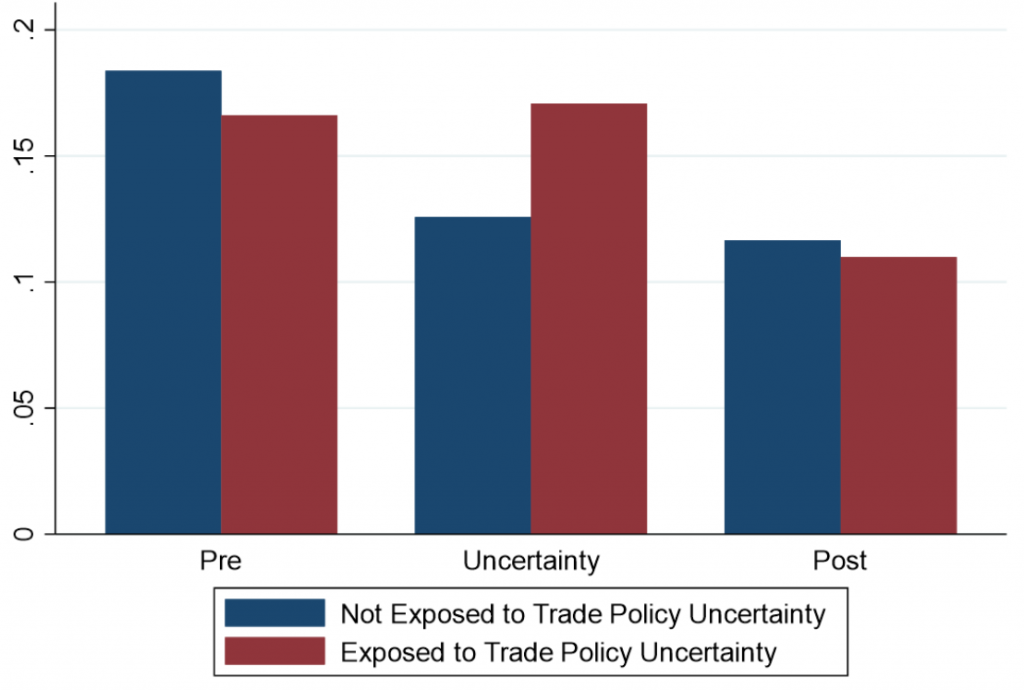

We follow Pierce and Schott (2016) and quantify the heterogeneous exposure to policy uncertainty via the “NTR gap,” defined as the difference between the non-NTR rates, to which tariffs would have risen if annual renewal had failed, and the NTR rates. A first important empirical stylized fact we uncover is in Figure 1 below. U.S. tradeable industries more exposed to trade policy uncertainty experienced significantly higher stock returns than less exposed industries in the 1990-2001 period.

We confirm the pattern shown in the picture with a differences-in-differences specification, that controls for industry-time variation in firm fundamentals, and other contemporaneous US-China policy changes, such as the global Multi-Fiber Arrangement (MFA) and China’s accession to WTO. The difference in average returns for high and low NTR gap industries is significant at the 1% level.

Figure 1: Trade Policy Uncertainty and Stock Returns. Pre:1980-1989; Uncertainty: 1990-2001; Post: 2002-2007. Source: Bianconi, Esposito and Sammon (2019, 2020).

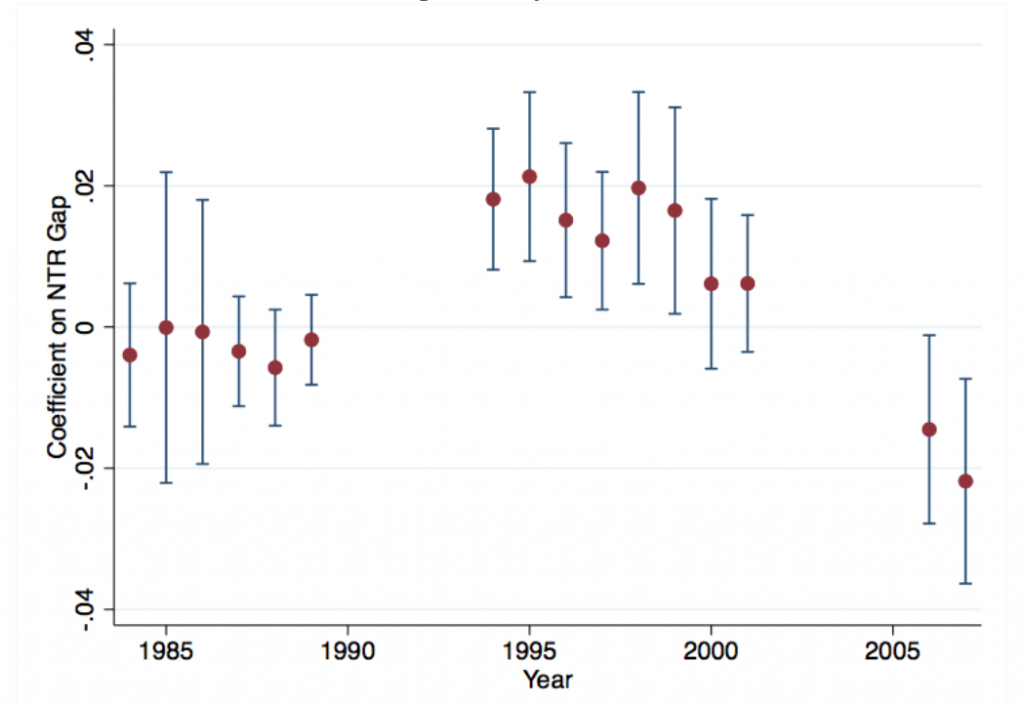

We further show in Figure 2 that the positive association between the NTR gap and stock returns was significant throughout the entire 1990-2001 period, but it was stronger in the first years of the decade. This is consistent with our premise that there was greater uncertainty about the legislation passage in the years 1990-1992, as suggested by the fact that in those years the House voted in favor of revoking NTR status to China.

We then argue that the higher average returns earned by more exposed sectors can be explained by a risk premium for exposure to TPU. Intuitively, during the TPU period, investors required additional compensation to hold stocks with exposure to this policy uncertainty. We show that a value-weighted portfolio, long high-gap industries and short low-gap industries, had average excess returns of 6% per year, over the 5 factors in Fama and French (2015), during the uncertainty period 1990-2001. Our portfolio’s excess return remains statistically significant after controlling for the globalization factor constructed in Barrot et al. (2019), which uses industry-level shipping costs to proxy for exposure to globalization. This means that TPU was a systematic factor that could not be diversified away and could not be explained by exposure to globalization.

Figure 2: Trade Policy Uncertainty and Stock Returns Dynamics. Pre:1980-1989; Uncertainty: 1990-2001; Post: 2002-2007. Source: Bianconi, Esposito and Sammon (2020).

Moreover, the risk premium was concentrated in industries with lower NTR tariff rates, and higher share of inputs expenditures from China. This suggests that exposure to globalization amplifies the effects of trade policy uncertainty and thus the associated risk premium.

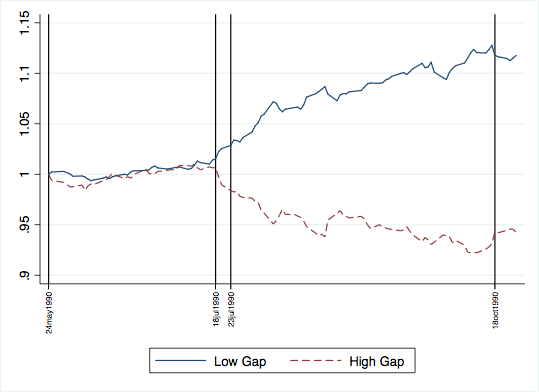

Lastly, in Figure 3 we document a large and significant drop in stock prices for industries with higher NTR gaps around the day in which the policy uncertainty reasonably began, i.e. the day when the first resolution to revoke NTR status was proposed at the House, on 07/23/1990. This is consistent with an increase in the discount rate due to higher uncertainty on future policies that depressed prices of more exposed industries, as in Pastor and Veronesi (2012).

Figure 3: Trade Policy Uncertainty and Stock Returns Dynamics. Source: Bianconi, Esposito and Sammon (2020).

Conclusions

In summary, we use quasi-experimental variation arising from China’s temporary NTR status to show that U.S. tradeable industries more exposed to trade policy uncertainty had significantly higher stock returns than less exposed industries between 1990 and 2001. Our estimated risk premium is substantial, industries highly exposed to policy uncertainty earned a risk premium of 6% per year relative to less exposed sectors. Among industries more exposed to trade policy uncertainty, the risk premium was larger in industry less protected from globalization, or that relied more heavily on imports from China. These amplifying factors provide evidence that uncertainty about trade policy matters more if an industry is directly exposed to globalization, either through low trade barriers or through the supply chain. Our approach is general in the sense that policy makers and practitioners can use risk premia to understand the effect of protracted uncertainty on investor’s beliefs and stock market behavior. Our results of a large risk premium for this type of uncertainty may serve as a word of caution to policy makers.

References

Baker, Scott R. R., Nicholas Bloom, Steven J. Davis, Kyle J. Kost (2019). Policy news and stock market volatility. Tech. rep., National Bureau of Economic Research.

Baker, Scott R., Nicholas Bloom, , Marco C. Sammon, Tasaneeya Viratyosin (2020) “The Unprecedented Stock Market Impact of COVID-19.” NBER Working Paper No. 26945, April.

Barrot, J.-N., Loualiche, E., Sauvagnat, J. (2019) “The globalization risk premium.” Journal of Finance, Volume 74, Issue5, October, Pages 2391-2439.

Bernanke, B. S. “Irreversibility, Uncertainty, and Cyclical Investment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, February 1983, Vol. 98, No. 1, pp. 85-106.

Bianconi, M. and Esposito, F. and Sammon, M., Trade Policy Uncertainty and Stock Returns (July 29, 2019, Last revised: April 3, 2020). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3340700 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3340700; Tufts University and Northwestern University-Kellog.

Davis, S. J. (2018) “Trump’s trade-policy uncertainty deters investment Many companies are reassessing spending plans.” Chicago Booth Review, 14 November 2018.

Davis, S. J., Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R., Miranda, J., Foote, C., Nagypal, E., (2006). Volatility and dispersion in business growth rates: Publicly traded versus privately held firms. NBER macroeconomics annual 21, 107–179.

Fama, E. F., French, K. R. (2015). A five-factor asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics 116, 1–22.

Handley, K., Limão, N. (2015). Trade and investment under policy uncertainty: theory and firm evidence. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 7 (4), 189–222.

Pastor, L., Veronesi, P. (2012). Uncertainty about government policy and stock prices. The Journal of Finance 67 (4), 1219–1264.

Pastor, L., Veronesi, P. (2013). Political uncertainty and risk premia. Journal of Financial Economics 110 (3), 520–545.

Pierce, J. R., Schott, P. K. (2016). The surprisingly swift decline of us manufacturing employment. The American Economic Review 106 (7), 1632–1662.

Thie post written by Marcelo Bianconi, Federico Esposito, and Marco Sammon.

Wait, this can’t be right…… didn’t donald trump have someone else write his book “Art of the Deal”?? Isn’t donald trump the “deal maker”?? Didn’t donald trump tell everyone he was great at making deals?? Seems like trump “got the shaft’.

https://www.cnbc.com/2020/05/11/coronavirus-us-exports-to-china-to-fall-short-of-phase-one-trade-deal-says-csis.html

Can someone check with FOX’s Drunko Pirro and see if I made a mistake somewhere??

Chinese imports from the US were always going to fall short.

I agree with you 100% Willie. Which shows what a horse crap tossing for Fox News viewers the entire exercise was.

For the record that doesn’t make China the devil either, but they should try harder to make promises they can actually keep. But I blame donald trump WAY more for this than Chinese government leaders—which is saying a lot coming from a man who is no fan of Xi Jinping and his crew.