Worried about currency debasement? Do we find out anything from the nominal exchange rate? In a flexible price monetary model (sometimes called the monetarist model of the exchange rate), changes in the money supply should be immediately reflected in the exchange rate.

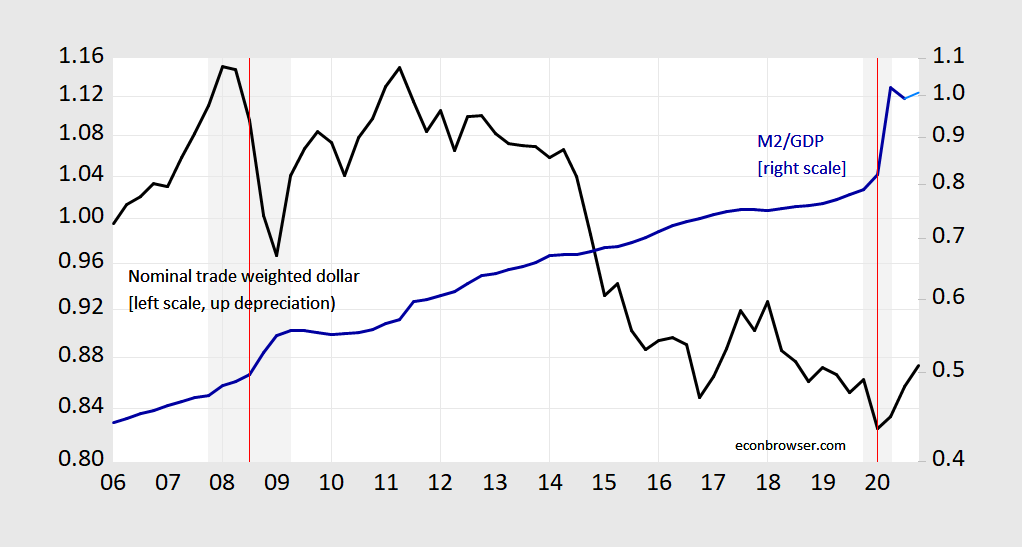

Here’s a plot of the trade weighted US dollar in nominal terms, shown so that a movement upward is a dollar depreciation. Also shown is M2 divided by real GDP. both are shown on a log scale. According to the simple monetarist model, the dollar should’ve depreciated with the increase in money.

Figure 1: Nominal trade weighted dollar exchange rate at end of period (black, left log scale, up is a depreciation), and M2 to real GDP (blue, right log scale). 2020Q4 is for data through November, and GDP from WSJ December survey mean. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Red lines at Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, and Covid-19 pandemic in US. Source: Fed and BEA via FRED, NBER, and author’s calculations.

Notice that the dollar appreciated at the time of the beginning of money expansion; this could be attributable to safe haven aspects. And further, rest-of-world money is not shown (in principle it’s US money relative to foreign that matters). As time has gone one, the dollar has depreciated as the US money supply has remained elevated.

US money/GDP has increased by about 22% since 2019Q4, while the nominal value of the dollar has decreased by about 12% (both in log terms). Whether this is a lot — representing imminent debasement — depends on how much you think the rest-of-world money supply has increased, as well as whether you think the monetarist model is right. [US M2 y/y growth is about 25%, euro area at about 10%, China and Japan at 9%, and UK at about 15% — not in log terms; https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/money_supply/]

I don’t – of course if one thinks prices are sticky, well, there should’ve probably been a bigger drop in the dollar given overshooting…

Well, overshooting assumes a pretty high level of not only mere rationality but full blown sophistication. Yes, it has been seen in history, e.g. the French franc in the 1920s, which was the poster boy that led Cassel and later Dornbusch to propose the model. But we know a lot of the time forex movements are flakey and hard to explain, much less predict.

And we know that you know this, Menzie, especially since you recently outed your connection with Meese, whose now ancient paper with Rogoff showed how hard it is for any model based on a theory to beat a random walk in forecasting forex movements.

Barkley Rosser: We’ve known about hump-shaped responses to monetary innovations for 25 years or so — so the mystery is not why there’s no full adjustment, but why there is under-response immediately after the shock (learning, bandwagon effects?) My 1995 paper with Meese was not as nihilistic as Meese-Rogoff; my most recent take is here.

Thanks for the first link, Menzie, which I think you have linked to previusly. Somehow I was not able to work the second one. Yes, that first paper fits the argument of poor short=term predictability but better longer run predictability.

There used to be a truism in international finance that there was a tendency to something like a tendency to a 15% regression toward PPP implied forex rates. Is that still thought to hold, at least sort of, or something like it?

Barkley Rosser: PPP deviation Half lives used to be thought of as about 5 years. Most recent research discussed here.

Hmmm. Well a half life of three years is pretty consistent with the old 15% per year truism, which adds up to about 45% in three years, just shy of a half life.

Weaker dollar=tighter credit with a lag. It means even more debt will be needed and the source regions drying up. China is nodding at Trump.

“China is nodding at Trump”? What does this mean? That the decline of the USD over the past year is due to China liking at Trump, disliking Trump, or going to sleep when they look at Trump? Really, TR, this is more incoherent than your usual posts here.

For anybody who thinks this recent movement is a big deal, just look at the figure Menzie put up here. The really big move over the last decade was the quite substantial increase in the value of the USD between 2014 and 2017, which probably did not help HRC get elected, especially in the rust belt. USD has been up and down since then by fairly small amounts and is about where it was when Trump first came in.

And, TR, I know you have a fixation on debt, but if in fact US was having a problem borrowing money, we would see it showing up in interest rates, but, heck, mortgage rates are hitting an all time low. Sorry, but not much there for you.

No, interest rates are the final collapse. The weaker the dollar becomes, the harder for consumers can borrow. Interest rates are when governments can’t borrow because the system collapses.

“final collapse”? Look, TR, we get it you are obsessed with your theory of imminent dollar collapse, but do please note that if you look at Menzie’s figure, the only time since 2006 the dollar has been higher than it is now has been during the last few years. It was much lower for most of this time period. It is declining right now, but not all that dramatically.

Maybe some day your story will come true, but it does not look at all imminent, despite some silly media stories.

Trade weighted dollar more correlated to money supply…or to the price of oil, which is traded in dollars?

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/POILBREUSDM

are you trying to say that oil controls the value of the dollar?

Correlation is not causation…but it makes sense that demand for the dollar would rise when oil prices rise, because buyers need more dollars to pay for it, whereas changes in interest rates do not seem to explain much…at least for a reserve currency like the dollar.

Sorry, JohnH, you do not even have correlation. Just look at Menzie’s figure since 2006. We has a major surge in value of the USD in 2008-09. What was happening to the price of oil then? It hit an all time peak of $147 per barrel, WTI, in June 2008, then plunged to $32 in Nov, only to gradually recover. So the USS rose sharply while the price of oil collapsed.

More recently in the last few years the USD has been very high in value while the price of oil has been low. However, very recently the price of oil has been rising again. What is the USD doing? Declining.

A bottom line is that there certainly is no causation because demand for USD to buy oil is a miniscule smidgen of the overall demand for the USD. They are almost completely disconnected, despite loud noises to the contrary in certain misinformed circles.

Isn’t it now pretty well established that fundamentals are not powerful drivers of exchange rates in the near term (5 year window) regardless of the model assumed?

In other words, the whole industry of near-term FX forecasting is bunk, yes?

I say this as someone who has been associated with the FX forecasting business for much of my career. I have long argued that our work should include an admission of fallibility, with very little success.

Macroduck: If one increases the money supply by 23% (in log terms) in pretty much two months, one might be expected to see some movement. Otherwise, it’s hard to see robust empirical linkages.

Yes. See the famous Meese-Rogoff paper from the 70s referred to in the discussion between me and Menzie. Hard to beat a random walk forecast in the short run, Md, even if there is some tendency to move toward PPP fundamental rates in the longer run, but not all that rapidly as it turns out.

Dollar-funded carry trades of all types are important here. When dollar-funded carry trades come under pressure, because they are levered, positions need to be closed quickly and this create fire-sale effects and a sudden appreciation in the dollar. The carry crash is a deflationary shock, because when volatility spikes during the crash, a lot of assets that were previously perceived as money-like are now suddenly perceived as risky. The demand for money that was previously satisfied by holding of financial assets then can only thus be satisfied by hold true cash, which the Fed has to supply. Thus, the spike in money supply is in large least part a replacement of “money” that was previously held in other financial assets. It’s not inflationary – at least in the short term – because it replacing a corresponding fall in moneyness of financial assets. The trade-weighted index isn’t the best way to look at this because the trade weights might not correspond to the carry flows, but it clearly picks up the unwinds in 2008 and 2020. I co-authored a book that explains this process called The Rise of Carry (www.riseofcarry.com)

Is it possible to have a large money supply and deflation at the same time? Interest rates would indicate low inflation, if not deflation, in spite of the cash that seems to be sloshing around. There is plenty of evidence we are not there now, but this discussion got me wondering.