Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, no enormous surge in capital investment appeared, above and beyond what could be explained by aggregate demand changes. From the conclusion to U.S. Investment Since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, by Emanuel Kopp, Daniel Leigh, Susanna Mursula, and Suchanan Tambunlertchai.

In the year following the passage of the TCJA, U.S. business investment grew strongly compared to pre-TCJA forecasts and outperformed investment growth in other major advanced economies.

Evidence suggests that the overriding factor supporting that growth has been the strength of U.S. aggregate demand, likely propelled by higher disposable household income or wealth gains due to the tax cuts and the government spending stimulus from the BBA which occurred simultaneously. While the increase in business investment is undoubtedly positive for economic activity as it increases capital stock and supports productive capacity, the aggregate demand boost could fade as the spending bill and personal income tax cuts expire.

Investment growth in 2018 was also below predictions based on the historical relation between tax cuts and investment as identified by a range of studies in the empirical literature. We estimate that policy uncertainty and, especially, the stronger corporate market power compared to previous postwar episodes of tax policy changes reduced the relative impact of the TCJA on business investment. The rise in corporate market power can account for a large part of the observed gap, offering a new explanation for why investment has not been stronger. Once these two factors are accounted for, other factors appear to have played a limited role (or their effects may have offset one another).

Our results suggest that in an environment of rising market power, corporate tax cuts become less effective at raising investment. They also support the notion that reducing economic policy uncertainty could result in further growth in business investment.

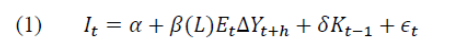

How much did a reduced user cost of capital spur investment. To investigate this, the authors use an accelerator model of investment (ex. structures) to show how much of actual investment can be explained without the user cost of capital. The accelerator model used is:

which is estimated over the 1983Q4-2016Q4 period. Then investment is forecasted out-of-sample using Consensus Forecasts of GDP for changes in income (this is also known as an ex post historical simulation). This results are shown in Figure 6:

Source: Kopp et al. (2019).

The fact that ex post investment (ex-structures) is only slightly above the simulated values suggests that the impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act via the changes in the user cost of capital is minimal (although aggregate demand effects coming from personal income tax cuts might have been important).

[The accelerator vs. neoclassical vs. other models of investment, discussed in this post.]

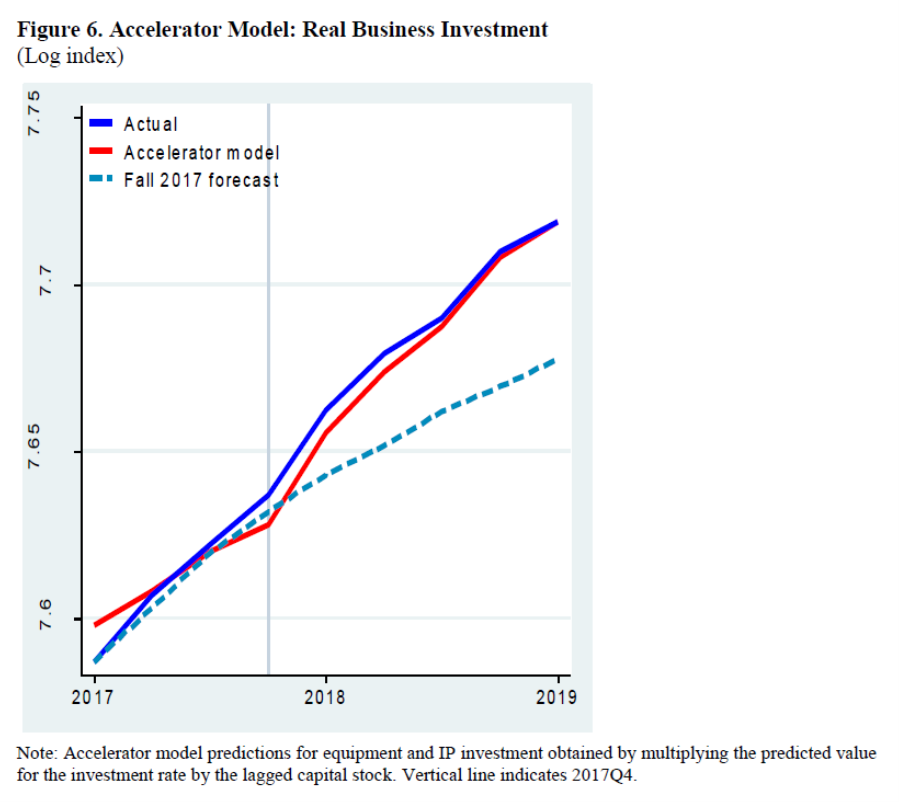

If firms did not devote increased cash flow to capital investment, what did they do? Figure 8 explains it all.

Source: Kopp et al. (2019).

If the decrease in the corporate tax rate in the TCJA had little impact on investment, it’s plausible that the increase in the tax rate associated with the American Jobs Plan will also have little impact (on investment).

See also the Congressional Research Service’s analysis of the TCJA (page 5 onward):

Second, the largest effects occurred in the first and second quarters of 2018, which allowed very little time to be the result of investments that must be planned in advance (even if the tax cut was anticipated in late 2017). Furthermore, structures growth rates were negative in the last two quarters.

Third, real growth in the subcategories of equipment, structures, and intellectual property products is inconsistent with the incentive effects of the tax change. Over the entire year, intellectual property products grew at the fastest rate (7.7%), equipment at a slightly lower rate (7.5%), and structures at 5.0%. To assess the incentive effects of the tax changes (which included a lower tax rate and faster depreciation for equipment), consider the change in the user cost of capital (or rental price of capital). It is the equivalent of the “price” of capital as an input (just as the wage is the price of labor input). It includes two costs of using capital: the opportunity cost of using funds (i.e., the required pretax rate of return on the asset) and depreciation (i.e., the cost of using up the asset). The user cost reflects the required rate of return at the margin (i.e., for an investment that earns just enough to be worth making). Estimates indicate that the user cost of capital for equipment declined by 2.7% and the user cost of structures declined by 11.7%, but the user cost of R&D (intellectual property products) increased by 3.4%. (See the Appendix for details on the derivation of these results.) The user cost of capital for equipment declined by less.

On the other side, Heritage presents its argument that the TCJA spurred investment here. Adam Michel tries to explain the 2018 decline in investment by appealing to economic policy uncertainty. The Kopp et al. argue that the decline attributable to economic policy uncertainty (as measured by the Baker, Bloom and Davis index) is modest relative to the implied increase in investment predicted by the models they examine.

PS: The Kopp et al. paper ascribes some of the decline in investment sensitivity to the user cost of capital to increasing corporate monopoly power. There is a citation to Krugman (2018) as an early proponent of the thesis of increasing monopoly power dampening the impact of corporate tax rate reductions. To wit:

Also, a substantial fraction of corporate profits really represents rewards to monopoly power, not returns on investment — and cutting taxes on monopoly profits is a pure giveaway, offering no reason to invest or hire.

“The Kopp et al. paper ascribes some of the decline in investment sensitivity to the user cost of capital to increasing corporate monopoly power. There is a citation to Krugman (2018) as an early proponent of the thesis of increasing monopoly power dampening the impact of corporate tax rate reductions.”

Say what? JohnH insists that Krugman does not discuss monopoly power. And of course Princeton Steve insists that economists never consider depreciation.

At the New York Times Krugman occupies one of the world’s most influential bully pulpits, and so far no one has explained why he doesn’t use it regularly to flog his concerns about what’s “killing the economy!” Of course, Krugman often mentions monopoly power, but rarely emphasizes and explains the problem like he did in the Irish Times, of all places!

Kuttner, 20 years ago explained why Krugman is conservatives ideal liberal: “Today, nearly all of the mainstream economics profession, whether nominally Republican or Democratic, has become the ally of laissez-faire conservatism. This has partly to do with the latent reverence for markets at the heart of neoclassical economics. It also reflects a professional resentment of non-economists as policy intellectuals who don’t adequately appreciate markets.

The career of Paul Krugman epitomizes, if in extreme form, how the conventions of the economics profession work to block a resurgence of liberal activism. Krugman is a self-described liberal. Yet his counsel on a wide range of issues is that nothing can be done. And he is far more charitable to very conservative fellow economists (Milton Friedman, Robert Lucas, Martin Feldstein) with whom he ostensibly disagrees than to fellow liberals such as Lester Thurow, Robert Reich, and Laura Tyson, whom he dismisses as pseudo-economists and mere “policy entrepreneurs.” On close examination, his disdain is often less about serious policy differences than about membership in the right disciplinary club.

As a sometime liberal, Krugman is resolutely critical of supply-siders (both as intellectual frauds and as nonmembers of the neoclassical fraternity). He has also written forcefully, including in this journal, on the widening inequality of income and wealth. But for the most part his message is that public remedy is a futile pursuit. Thus, Krugman is the conservative’s ideal liberal. He ridicules some of the most effective spokesmen for liberal economic policies, and he generally ratifies the conservative view that not much is worth trying because the market economy is doing about as well as it can.”

https://prospect.org/economy/state-debate-peddling-krugman/

A similar pattern was noted by Luke Savage over at Jacobin Magazine: “Paul Krugman, long associated with the push towards universal healthcare in the United States, doesn’t think Democratic presidential candidates should be running on Medicare for All in 2020…

It’s perplexing, to say the least, that one of America’s most prominent liberal advocates for healthcare reform has also taken to warning people about the dangers of pursuing the very model he himself suggests is best. Krugman’s well-established hostility to Bernie Sanders, going back to 2016, seems equally confusing given the innumerable columns he’s penned savaging centrist Democrats for their timidity and general refusal to push for transformative change.

Krugman’s thought, here and elsewhere, thus presents us with an initially baffling contradiction.

Having spent more than ten years advocating for a sweeping overhaul of America’s healthcare system, he is now warning Democrats about the dangers of actually carrying one out. And having once called for a “new-New Deal,” he is again signalling his opposition to the most popular and electorally viable Democratic candidate in a generation who aspires to anything of the kind. ”

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2019/04/the-diffidence-of-a-liberal

Krugman’s approach to Bernie’s 2016 healthcare proposal left me dismayed and distrustful. Instead of savaging the Sanders plan, why not offer constructive criticism, and adapt it to make it viable?

In any case, it seems that Krugman takes the position of supporting beneficial change to improve the general welfare…until the prospect of its being realized becomes too real, and he suddenly, inexplicable backs away. What would the economics version of coitus interruptus be called?

JohnH: You have not responded at all to my examples of Krugman discussing monopoly/oligopoly both in NYT columns and in his textbook, as well as in academic writings (esp. New Trade Theory), contra your assertions. All you have done is write another screed decrying Krugman’s failure to be “purer than thou”. I wish you would acknowledge your (gross) failure to correctly characterize Dr. Krugman’s ouvre.

He’s been doing this ever since Krugman did not endorse Bernie Sanders. Five years of nonstop rants. BTW – the central premise of his latest rant goes like this. It is better to get an oped a week in the NYTimes than it is to be on the Counsel of Economic Advisors. Who knew Maureen Dowd was so influential in terms of economic policy making?

@ Menzie

I thought Krugman’s most recent “newsletter” illuminating, and refreshing in the sense he was willing to admit a small amount of error in his prior appraisals of the donald trump tax cuts. I will basically lift verbatim Krugman’s words for fear of me ruining the core of his written exposition:

“But these predictions missed a key point: most business assets are fairly short-lived. Equipment and software aren’t like houses, which have a useful life measured in decades if not generations. They’re more like cars, which generally get replaced after a few years — in fact, most business investment is even less durable than cars, generally wearing out or becoming obsolete quite fast.”

…….. Krugman pushes onward

“And demand for short-lived assets isn’t very sensitive to the cost of capital. The demand for houses depends hugely on the interest rate borrowers have to pay; the demand for cars only depends a bit on the interest rate charged on car loans. That’s why monetary policy mainly works through housing, not consumer durables or business investment. And the short lives of business assets dilute the already weak effect of taxes on investment decisions.”

If someone else in this thread had already pointed this out and I am being redundant I apologize.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/09/opinion/trump-corporate-tax-reform.html?action=click&module=Opinion&pgtype=Homepage

That Heritage paper goes full spin mode:

“In reality, the corporate tax cut supports job and wage growth. Key economic indicators and pre-tax-reform economic projections show clearly that the tax cuts worked as intended with significant benefits for working Americans. These gains were undermined by trade uncertainty, costly tariffs, and in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic.

Disentangling the effects of lower taxes, simultaneous regulatory reform, increased trade costs, growing government debt, and the COVID-19 economic shock makes any assessment of the TCJA a challenging task. However, properly assessing the 2017 tax cuts’ economic history is crucial for lawmakers who will consider whether to raise taxes in the coming years.”

Sentence 3 suggests TCJA would have worked wonders had Trump not been a total screw up. Sentence 4 admits carefully analyzing the effects of the reduction in the corporate tax rate is not all that easy so excuse this writer for just being Steno Sue for Mitch McConnel.

It would be great if Menzie update this November 2019 post:

https://econbrowser.com/archives/2019/11/gross-vs-net-investment-pre-and-post-tcja

He notes that while gross nonresidential investment had increased very slightly, net investment actually fell. As I have noted quite often all of these calculations should consider both depreciation (which Menzie did) and our much of this investment was purchased by foreigners.

Of course I was reminded of this post by Menzie himself in a few posts back when Princeton Steve was making the usual jerk of himself by falsely accusing economists of not recognizing the role of depreciation.

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/15/opinion/tax-cut-fail-trump.html

November 15, 2018

Why Was Trump’s Tax Cut a Fizzle?

The G.O.P.’s only legislative achievement has been a big disappointment.

By Paul Krugman

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/08/opinion/biden-corporate-taxes.html

April 8, 2021

Biden, Yellen and the War on Leprechauns

Bribing corporations with low taxes isn’t the way to create jobs.

By Paul Krugman

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/09/opinion/trump-corporate-tax-reform.html

April 9, 2021

Krugman Wonks Out: Why Was Trump’s Signature Policy Such a Flop?

The abject failure surprised even the critics.

By Paul Krugman

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=D2nw

January 15, 2018

Share of Gross Domestic Product for Private Fixed Nonresidential Investment Spending, 2010-2020

Krugman has an interesting paragraph:

“As the plan’s name suggests, the administration’s experts–at this point it’s hard to find a tax expert who hasn’t joined the Biden team–do believe that there are aspects of the U.S. tax code that have created an incentive to move jobs abroad. But they see the problem as the consequence of details of the tax code rather than the overall burden of taxation.”

The tax code has become too complex to enforce as the big shots can exploit all the holes in the Swiss cheese Congress put into over the years (TCJA made things very complicated) to bilk multinationals for huge consulting fees in order to shift even more income to tax havens. Get rid of FDII, GILTI, BEAT, etc and just enforce transfer pricing. Simplicity helps the companies that don’t cheat while it could rake in a lot more taxes from the likes of Big Pharma as well as Apple, Facebook, Google, etc.

Krugman’s war on leprechauns without that NY Times firewall:

https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2021/apr/10/paul-kruman-the-war-on-leprechauns/

Hey I’m Irish so a war on Leprechauns would normally upset me but when Krugman talks about creative accounting it is transfer pricing abuse on steroids. A war on this is definitely needed.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=naQD

January 30, 2018

Share of Gross Domestic Product for Private Fixed Nonresidential Investment Spending, 1948-2020

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=CELr

January 30, 2018

Private Investment: Intellectual Property Research and Development as a share of Gross Domestic Product, 1948-2020

Is it possible that higher corporate marginal tax rates encourage capital investment? Higher marginal tax rates allow more benefit to cash flow from depreciation expense compared to lower marginal tax rates. Using data from the Tax Policy Center, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/statistics/marginal-corporate-tax-rates I notice that a simple regression model regressing Real Gross Private Domestic Investment, FRED series GPDIC1 https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GPDIC1 on marginal corporate tax rates and on recession, FRED series USRECM, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/USRECM, a positive coefficient results on corporate tax rates. Perhaps my model is not proper or adequate, but just a thought. I used quarterly data from 1957 to 2019.

Wow – this will shock Princeton Steve that economists have considered things like depreciation and tax policy EVEN the late Frank Wykoff co-authored a paper with Charles Hulten some 41 years ago. I provided a link so Princeton Pompous can read the 1980 paper but something tells me that he will not.

That Tax Policy Center chart shows that the corporate tax rate was 40% or more from 1950 to 1987. And if you check the BEA data, you will see real GDP growth was quite strong and investment demand as a share of GDP was quite healthy until that 1981 Reagan tax cut. Of course no supply sider will ever admit this reality.

That Tax Policy Center chart noted something else which relates to the 1st caller to his interview with the local Wisconsin show. This caller was wondering about how Biden’s increase in the corporate tax rate from 21% to 28% would effect small businesses. Note before TCJA large businesses may have paid 35% rates but small businesses paid 15%. TCJA raised the corporate tax rate on small businesses from 15% to 21%.

More on the 1/6 timeline:

https://apnews.com/article/capitol-siege-army-racial-injustice-riots-only-on-ap-480e95d9d075a0a946e837c3156cdcb9

Pence called Defense Sec. Christopher Miller at 4:08PM demanding he clear the capitol. Nothing happened for another hour when the National Guard finally got the clearance to move in almost 3.5 hours after they knew they would be needed. Of course the National Guard was not given clearance until after 5PM and no one else from the Pentagon ever intervened.

Complete and utter incompetence? Or just maybe the delay planned by the Commander in Chief Donald Trump.

Has this been the Bruce Hall scheme to get to cut in line receiving the vaccine? Start by blatantly ignoring his own governor’s sensible advice to social distance and wear masks and encouraging his neighbors to also be horribly irresponsible. Deny this will lead to a surge in cases even as this lying village idiot knows his advocated irresponsibility will lead to more cases and deaths. And when that happens begs to be put first. After all screw that suckers in states that did the right thing.

https://talkingpointsmemo.com/news/whitmer-michigan-covid-vaccine-surge

A couple of comments:

(1) I see that the GOP is up to its usual word games. A few months ago they called the American Rescue Plan the COVID Relief Plan and then accused the Biden Administration of being dishonest because it contained stuff above and beyond strictly COVID relief. Of course, the Biden Administration never said it was only strictly COVID relief, that was simply a deliberate misinterpretation that Team McConnell gave it. And now they’re playing the same game with the American Jobs Plan. This morning I heard Chris Christie accuse the Administration of dishonesty because what he called the “infrastructure” plan contained more than traditional infrastructure. Maybe that’s because it’s not called the “Infrastructure Plan” but the American Jobs Plan. So just who is being dishonest here?

(2) Way back when I rode to school on the backs of dinosaurs I was always taught that the effect of the corporate income tax on the physical capital stock was ambiguous. For example, ignoring inflation, depreciation, off-shoring and assuming that capital is financed by borrowing costs that are fully deductible, a change in the corporate tax rate has (to a first approximation) no effect on capital investment. The ambiguity in the effects of a change in the corporate income tax rate come from factors like inflation, off-shoring, depreciation allowances, interest costs, the deductibility of interest, and how capital investment is financed. The reason the corporate tax rate itself doesn’t matter is that firms will target the physical capital stock such that the after-tax marginal product of capital equals the after-tax rental cost of capital irrespective of what that tax rate happens to be. Let’s take an extreme example that sets aside the peculiar factors that cause ambiguity and focus on the baseline case. Suppose there is no corporate tax and the interest rate is 10%. The firm will set the capital stock such that the marginal product of capital equals 10%. Now suppose the government introduces a tax of 21%. With that same capital stock the after-tax marginal product of capital will fall to 7.9%, because the firm will pay 21% of its profits in taxes; however, if the interest costs are deductible, the firm gets to deduct 21% of its interest payments from its taxes, so the after-tax rental cost of capital will also be 7.9%. If that rate is then raised to 28% the after-tax marginal product of capital falls to 7.2%, but the after-tax rental cost of capital also falls to 7.2%. But notice that the actual physical capital stock is the same in all three cases. Corporate fat cats will make less money, but the corporate tax rate itself doesn’t change the physical capital investment.

Your (2) reminds me a lot of this paper:

“Do Income Taxes Reduce the Effectiveness of Monetary Policy?” with Rudolph C. Blitz, American Economic Review, 66 (1), June 1976, pp. 168-173.

Back in my Vanderbilt days, it was required reading. I’m sure you’d appreciate their modeling.

A slight different perspective is offered here: https://taxfoundation.org/economics-stock-buybacks/

The perception that the choice is between stock buybacks or investment is false.[16] Companies generally only consider engaging in stock buybacks when they have exhausted their investment opportunities: it is residual cash flow, or what is left over after companies have made their investments, that is used for buybacks.[17] For companies with more cash than investment opportunities, the real choice is between buybacks or having the cash sit effectively idle. Focusing attention on the initial occurrence of a stock buyback misses the greater context: stock buybacks are a normal function that can help transfer capital to new and growing firms, leading to broad, long-run benefits.

Whether or not that is accurate in this instance is up for debate. I guess my question is: what tax rate between 0% and 100% represents the “sweet spot”, the optimum, for economic growth and corporate investment … and is that dependent on other aspects of the tax code?

Bruce Hall: Well in a Modigliani-Miller world, that assertion might be true. Do you think we live in such a world.

Modigliani-Miller may be one of the key seminal concepts from the early days of financial economics and yet I’ll bet the ranch Bruce “no relationship to Robert” Hall has no clue who Merton Miller or Franco Modigliani even are.

We appear to live in a very strange world whether or not Franco and Merton are defining it. What about Schlagenhauf at the St. Louis Fed?

https://www.stlouisfed.org/timely-topics/optimal-corporate-income-tax-rate

So what we studied is the following scenario: We wanted a model that had different sized firms, because firms grow over time. We wanted to have big and small firms in the model. We wanted to have them choose the type of legal organization. And then we started studying that framework, and what do we find? If we lower the corporate income tax, would that generate jobs? Possibly. It depends on what the income tax rate is lowered to. But let’s take what we found was close to the optimal tax rate, about a 10 percent corporate income tax rate. Now remember, when the Trump plan started, the tax rate was about 28.5 percent approximately, and it was lowered to 21 percent. So we actually find, for our structure, the optimal tax rate is lower.

Now what else do we find? We find that at 10 percent we get more output, a 3 percent increase in output when all the features kind of wash out and we find the new equilibrium in the long run. But also what we find is employment will grow by about 1.3 percent. So there is employment growth out of this.

So the question has to be: Why? What generated this? Well, there’s a feeling in the economics profession that a lot of growth potential comes from startups, small firms growing into big firms. So we have that in our model.

Also, we don’t allow deficits. We have to pay for that right away in the model. That’s the tradition in economic research. We want revenue neutrality, it’s called. So we raise the personal income tax to pay for that loss of revenue.

Now that turns out to be an important feature of what’s going on. The corporate income tax is going to spur employment growth eventually in C-corporations. But what also happens is S-corporations who do not want to suffer the double taxation that a C-corporation does says, “Wait a minute. Personal income tax rates went up, C-corporations went down. Now my penalty for double taxation has been lessened. I still suffer, but I still pay and I still have double taxation. But what’s the benefit?” These highly productive entrepreneurs now have access to better capital because they’re less constrained in their funding by being a C-corporation, and that’s the transmission that we discovered will allow there to be employment growth and output growth.

Perhaps economic models and climate models have something in common.

Franco or Merton? Show some respect as both received Nobel Prize awards in economics. I would tell you what their contributions were but we know they would go over your little pea brain.

pgl, awwww. That’s so nice of you to talk about respect.

Bruce Hall

April 11, 2021 at 3:43 pm

His response was Bruce’s usual nonsubstantive whining. But let’s see if Kelly Anne’s favorite troll could bother to tell us what Don’s definition of optimal even is. Oh wait – he does not know.

What a lot of babble speak modeling. Of course you have no clue what his modeling was even about. All you wanted was a claim that the optimal tax rate = 10%. In his far fetched modeling of course. BTW – do you even know the difference between a C corporation v. a S corporation? I didn’t think so.

BTW – where was that published? Not the AER. Not the JPE. Oh yea the Ladies Daily Flower Report.

pgl, “far fetched”… St. Louis Fed economist. Okay. I’m sure you’ve done better. btw, I had a nice S corp on the side (part time) that put my three sons through college without them incurring any debt and gave me some nice perks along the way. Have you run a business or do you just criticize?

Did you read the article? Or are you just upset because he stated 10% instead of 35%?

“Did you read the article?”

I did read it but did you? Do you have any clue how Don defined optimal? Of course not. A worthless discussion provided to us by a worthless troll.

Gee Bruce can get the last name of a FSU professor right but he cannot note the proper names of two Nobel Prize winners in economics – one that teached finance at Chicago and the other who taught at MIT. But does Bruce have even the slightest clue of the publication record of FSU’s “Don”?

https://muckrack.com/don-schlagenhauf/articles

Pretty damn short and mostly on issues involving debt. Tax policy and investment demand not so much.

Another example of how Bruce “no relationship to Robert” Hall just pulls garbage out of Kelly Anne Conway’s trash can.

pgl,

you should show a little respect… or don’t you remember your recent comment?

pgl,

Actually Schlagenhuaf is a reasonably substantial figure. He has mostly been based at the St. Louis Fed research shop and was only a short time visitor at FSU. He has pubbed in high quality journals over time, without dragging through them, and the paper that seems closest to this one Bruce Hall linked to a discussion of (not to the paper itself, which would have been more useful so we could actually see the model) was published in the AEJ: Macroeconomics journal, which has become a top of the line journal. I suspect the model is not some pile of nonsense.

Given that we do not know really what is in it, it certainly looks that allowing for all the legal variations of types of firms, which seems to be the main focus of the paper, would allow for a deviation from MM, whatever BH knows or does not know about them. It seems that what the model shows is that growth of real investment and employment from a corporate tax cut not going below 10% comes from new startups.

This leads to an obvious test for this model: did the TCJA lead to an increase in startups and more importantly to an increase in employment due to them? The answer is mixed, but definitely not impressive.

So I looked at Stastica numbers (do not know if FRED at St. Louis Fed has numbers on this). For rate of new startups there was a low in 2009Q4 of 2.7%. After a few years this moved up to fluctuate around 3.0%, with a jump at end of 2014 and early 2015 to 3.3% before falling back to about the 3.0% rate. In the immediate aftermath of the TCJA in 2017 it looks that the rate might have risen to about 3.1%, with a final burst in 2019Q4 up to 3.4% before plunging to 2.7% in 2020Q4, last reported rate.

That looks like there might have been a slight positive effect of the Trump tax cut along lines forecast by this model of Schlagenhaug et al. However, if we look at employment there seems to be nothing there at all, indeed possibly a negative effect. Starting in 2010 quarterly numbers for new employment from startups was about 2.5 million. This steadily and gradually rose until 2016 when this quarterly number hit 3.3 million. What has happened since. Not a thing. That number went and remained flat including to the end of 2019, no numbers since.

If anything a possible intepretation of that would be that prior to the Trump tax cut new employment from startups was steadily rising, but the Trump tax cut halted that increase, although I grant that the halt actually arrived about a year earlier. But it certainly did not stimulate any employment growth, even if there may have been some uptick in the number of new startups. But they did not deliver the employment increase goody.

Why did you not cite the key statement here?

“The TCJA is expected to boost investment, leading to a larger economy, higher wages, and more jobs, but these expectations will not be realized immediately. It will take time for the long-run economic effects of the TCJA to develop, as it takes time for companies to plan and build new investments, and additional time for workers to use those new investments to become more productive, translating to higher wages.”

Most of the standard Econ 101 models say that the boost to investment demand and growth in the short-run is tiny. Oh wait – admitting this little reality would piss off your political masters.

“what tax rate between 0% and 100% represents the “sweet spot”, the optimum, for economic growth and corporate investment … and is that dependent on other aspects of the tax code?”

2slug has a very informative answer in the comment section here. Not that you would ever understand it.

From the Congressional Research Service paper:

‘During the debate about taxes, however, arguments were made that these corporate tax cuts would benefit workers due to growth in investment and the capital stock. After enactment, CBO projected these effects to be relatively small, with increases in labor productivity (which should affect the wage rate) negligible in 2018 and growing to 0.3% of GDP after 10 years. CBO projected that the total wage bill would grow because of the increase in employment and hours per worker of 0.2% in 2018. The labor supply response would rise through 2024, peaking at 0.8% and then decline as the individual tax cuts expired. A Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) October 2017 study suggested a corporate rate reduction from 35% to 20%, if enacted, would eventually increase the average household’s income by a conservative $4,000 a year. This was a longer-run estimate, but the study also estimated that workers would immediately get a significant share (30%) of the profits repatriated from abroad due to tax changes. Another CEA October 2017 report suggested wages could increase by up to $9,000 with such a corporate rate change using more optimistic assumptions. While the CEA study with respect to the $4,000 to $9,000 amounts referred to a long-term effect, the study was portrayed by the Administration as indicating an immediate effect.’

The CRS like the Tax Foundation properly notes that the short-term effect on wages is quite small. This short-run v. long-run distinction is important and well known to anyone who studies these issues. But supply-side liars like Bruce Hall and Team Trump almost always tells us the very long-run impact will occur very quickly.

pgl,

But supply-side liars like Bruce Hall and Team Trump almost always tells us the very long-run impact will occur very quickly.

Hmmm. I don’t recall saying that. Corporate investment can return fairly immediate gains when it addresses unmet demand and results in increased production. Some investment will be necessary simply to stay competitive as markets and competitors change, for example, transitioning from 3G to 4G to 5G cellular networks and returns might not be spectacular or quick and may not actually generate that much more revenue, but failure to invest can put you out of business. Of course, that also depends on the tax considerations, both rate and depreciation schedules.

Are the huge investments the automobile companies making in meeting the government’s mandates for electric vehicles improving the bottom line, employment, and shareholder returns immediately? Will increasing their tax rates make those increase those investments? The government certainly gets more spending money. So, will the government now make the investments for the automobile companies as the corporate taxes increase?

And, of course, corporations have to manage for factors other than taxes, such as economic downturns when governors shut down the economy. Sure, you can model for all of that; you just can’t plan for all of that. Stuff happens between the blackboard and the production line. What did the M&M formulae have to say about COVID-19 (or 2008-09)? There’s an old saying that “No battle plan survives contact with the enemy.” No model survives contact with reality.

Soooo… what’s the optimal tax rate for corporations (you skirted that nicely)? 10%? 21%? 28%? 35%? More? And, more importantly, for whom?

Wow an attempt at substance. What a refreshing change. Of course you do not get the fact that you gave a Keynesian answer. Supply-siders are talking about something else. But this is what we have come to expect from Bruce “no relationship to Robert” Hall.

“Are the huge investments the automobile companies making in meeting the government’s mandates for electric vehicles improving the bottom line, employment, and shareholder returns immediately?”

My Lord – Bruce “no relation to Robert” Hall is so incredibly stupid that he does not even know the criteria for these discussions. Yes shareholders get more after-tax profits but that is clearly not what was promised. What was promised is a larger capital stock which would increase labor productivity. Which has not happened. But Bruce Hall does not care as this troll does not even get what the damn discussion is even about. He is THAT stupid.

Bruce Hall Corporate investment can return fairly immediate gains when it addresses unmet demand and results in increased production.

Those kinds of returns are not considered profits in the sense that economists understand the term. An accountant might, but not an economist. The kind of returns you described are considered economic rents due to first mover scarcity advantages. Profits are the returns to capital’s marginal product.

So, will the government now make the investments for the automobile companies as the corporate taxes increase?

Well, yes. That’s why Biden included a nationwide network of charging stations in the AJP.

There’s an old saying that “No battle plan survives contact with the enemy.”

How would you know? Have you ever actually seen a battle plan?

what’s the optimal tax rate for corporations

Optimal with respect to what? With respect to maximizing tax revenues? With respect to maximizing shareholder returns?

“Optimal with respect to what? With respect to maximizing tax revenues? With respect to maximizing shareholder returns?”

Bruce’s answer is indeed shareholder returns. Gee cutting taxes on profits can increase after-tax profits. Stop the presses!

Of course anyone who remotely get this debate would define the criteria not in terms of profits but per capita income aka the impact on labor productivity.

But of course Bruce “no relationship to Robert” Hall first ducks this question as he has no clue. And when he provides an answer – it is the absurd criteria that tax policy should be solely about increasing after-tax profits. Robert Solow must be laughing from his grade. Oh wait – Bruce does not even know who Solow even is. Never mind!

Robert Solow must be laughing from his grade

I hope you didn’t mean “grave”!!! Solow is still (barely) alive as I write this. Thank God. Don’t want to jinx Solow…he’s the last of the greatest generation.

“what’s the optimal tax rate for corporations”

Your FSU fellow distinguished between companies like Apple and start ups but you don’t. Huh! Yes TCJA lowered Apple’s tax rate from 35% to 21% but remember old Don was talking about startups, which faced an increase in the tax rate from 15% to 21%.

I guess you are the one that needs to address whether than was “optimal” even if you have no clue what the term optimal means on this context.

Oh wait your boss Kelly Anne Conway forget to tell you that TCJA raised tax rates on small businesses and startups. She is such a bitch to you but you play Steno Sue for her anyway?!

Bruce Hall For the sake of argument let’s assume that what you say is true. In that case, if investment opportunities were so scarce, then what was the justification for the TCJA? The arguments for the TCJA assumed that there were plenty of investment opportunities just sitting out waiting to be financed.

BTW, you should take everything you read from the Tax Foundation with a very large shovel full of salt. It’s mainly a hack organization whose sole purpose in life is to throw up a enough smoke and econ sounding stuff to fool people who don’t actually know any econ.

Ask him a more fundamental question as in what are the Modigliani-Miller propositions and how do they relate to this discussion. Of course Bruce “no relationship to Robert” Hall does not know.

Notice how this troll talks about Franco and Merton. Is that like Bert and Ernie to this Trumpian troll? Oh wait Trump used to call two prominent members of Congress Chuck and Nancy.

The Tax Foundation author can certainly find a textbook to validate the claim that investment takes precedence over buybacks, but it would be nice to see evidence to back up the claim.

The textbook assumption is that firms set the marginal this equal to the marginal that in maki g decisions, but surveys of business investment plans find that hurdle rates are widely used in making investment decisions. Hurdle rates generally do not vary with borrowing rates – the marginal this is not set equal to the marginal that. The textbook does not reflect reality in this case.

The period of low interest rates has not been a period of strong non-residential fixed investment. Nor has it been a particularly strong period for net cashflow. It jas been a strong period for both corporate borrowing and equity buybacks.

So the assertion that investment opportunities are exhausted before buybacks are done and the assertion that buybacks are conditioned on cashflow are both contrary to the evidence.

Heres the other thing. The bad thing. Most everybody who pays attention to the financial and investment behavior of U.S. firms knows all this. It’s not controversial. It’s taken for granted in discussion. The Tax Foundation is either unfamiliar with the actual behavior of businesses, or is part of the big lie in support of enriching the rich. Either way, this “residual cashflow drives buybacks” stuff is bunk.

The commies at the WSJ reports the CEO compensation soared in 2020 even as the rest of us suffered:

https://www.wsj.com/articles/covid-19-brought-the-economy-to-its-knees-but-ceo-pay-surged-11618142400?mod=hp_lead_pos1

Why? Not because their companies necessarily did better – more like they had their buddies on the Board of Directors restate the compensation packages so they could do well as the rest of us did not.

And these crooks complain about the idea of a 28% corporate tax rate?

The CRS paper has an appendix on the user cost of capital which begins with:

The user cost of capital is the sum of the pretax required return for a marginal investment and the economic depreciation, or

(1) C = R/(1-t)+d

Where C is the user cost, R is the required after-tax return, t is the effective marginal rate, and d is the economic depreciation rate. Economic depreciation is the decline in the value of the asset in real terms, and belongs in the cost term because it compensates the investor for the wearing away,

or using up, of the asset.

Huh – the economists at the CRS include depreciation in their analysis. And Princeton Steve has been lecturing us how economists ignore this concept. Of course most of us realize that estimating the economic rate of depreciation is not easy. But I hear Princeton Steve tells his clients it is easy to estimate depreciation. Really?

I wonder how Steven Kopits would estimate the expected depreciation of stranded carbon-intensive capital investment.

Funny but the idea that economic depreciation might be higher than accountant’s measure of depreciation in a world of obsolete technologies was key in Andantech v. Commissioner which was an important win for the IRS combatting the scam known as Lease in Lease Out (LILO) transactions.

Skip all the legal issues as it came down to whether the formal owner of computer mainframes purchased in September 1993 for $125 million received adequate lease payments or not. The taxpayer’s expert argued that the expected return to capital = 6.5% if the expected value of the mainframes five years later = $25 million. But the credible evidence suggested that this junk would be at best $10 million in September 1998.

But of course Princeton Steve thinks reliable estimates of such matters is easy. Maybe the taxpayer should have hired him as their expert witness!

Simply, and impossibly, we should treat corporations the same way top (and now even medium) talent in the film industry demands, and gets, from production companies. Demand gross points, i.e. a percentage of gross revenues.

It has the core virtue of indifference to the vagaries of the marketplace, almost an invisible hand so to speak.

Taxing just profits is monkey points, to use a pejorative industry phrase.

I know, too much time spent in La-La land…

Not to rain on anybody’s parade, but the Fed’s monetary stimulus and ZIRP didn’t lead to much of an increase in investment either, despite its vaunted theoretical power. Ten years later, private investment was only 12.5% higher than in 2006. In Trump’s four years, it rose 7%.

When it comes to investment, it appears that neither the monetarists nor the tax cutters adopted policies that produced anything to cheer about…which brings us back to the need for government spending as stimulus.

JohnH: Gee, I remember teaching my students that the Fed policy would have limited impact by virtue of (in IS-LM) the ZLB with low expected inflation (which means it is hard to get the real rate down to the natural rate). Which is why both Bernanke and Powell argued for more fiscal stimulus.

JohnH thinks you and I are monetarists? Excuse me?

We had a long and protracted disagreement about whether Bernanke ever advocated fiscal stimulus after 2010. No one managed to cite an instance, though it was a widely held perception. Instead, the Fed chose to rely exclusively on monetary policy through many years of anemic growth in investment. There was much much discussion in economics circles about the causes, many insisting that ZIRP was bound to work, it was theoretically sound. Others argued that low rates were not by themselves sufficient motivation for investment (you can lead a horse to water…). Bernanke, by refusing to publicly endorse fiscal stimulus, obviously endorsed the former. Others, like me, who have actual experience in the corporate investment decision-making process, endorsed the latter view, which proved to be right.

Unfortunately, policy makers after doing an outstanding at the outset of the Great Recession, blew it afterwards. They are really in no position to criticize Trump, bad as his investment numbers were.

JohnH: Well, took me 30 seconds: https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/testimony/bernanke20130522a.htm

This from Bernanke has been pointed out to JohnH each and every time he made that claim for the past 5 years. Give him a couple of weeks – and he will be repeating this claim. Is he a liar or just a victim of dementia? Hard to tell.

“We had a long and protracted disagreement about whether Bernanke ever advocated fiscal stimulus after 2010. No one managed to cite an instance, though it was a widely held perception.”

Seriously dude – either you have dementia or you are lying as usual. Our host has already pointed out where Bernanke advocated fiscal stimulus in 2013 – three years after you just claimed he stopped doing so in 2010. Look – we have known you are either a liar or incredibly stupid for five years now. Isn’t it time to stop embarrassing your poor mom. m

Our host has asked us to provide data to back up claims. Funny you did note so permit me:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GPDIC1

I notice three things you just skipped over. First was the Great Recession which started in late 2007 which was accompanied by a huge drop off in real investment.

But then we got the recovery which started in late 2009 and carried into the early year of Trump’s “four years”. Yea I get Trump wants to claim credit for this recovery but he is a blatant liar. Then again so are you.

But I guess you did not notice that investment demand plummeted in the last year he was in office. Now if you had any interest in an honest discussion – you might have noted this fact.

But I do see why you did not provide this link. It exposes how dishonest your comment was.

Since Krugman keeps coming up, let’s just note that his whole IS/LM schtick during the financial crisis and its aftermath eas predicated on the idea that rate policy has limited power with rates near zero. The weakened role for interest rates showed up as a special case in case in Lord Keynes’ writing, if memory serves.

So, no, no vaunted theoretical power in current circumstances. The Fed uses the tools it has and asks Congress to use fiscal tools, with no particular claim that Fed tools are powerful. They a simply all the tools available to the Fed.

Barkley Rosser

April 11, 2021 at 4:38 pm

pgl,

Actually Schlagenhuaf is a reasonably substantial figure.

Thanks for an informed and useful comment. I do not expect Bruce Hall to bother to do anything like this. No – this fool is trying to figure out how to solve COVID-19 with the Modigliani and Miller propositions. Yea – he really is THAT stupid.

But let’s note one thing about TCJA that we learned from the Tax Foundation. Before TCJA small businesses paid a 15% corporate profits rate. TCJA raised that rate to 21%. Again a wee fact that Bruce “no relationship to Robert” Hall even knew.

pgl,

Somehow I had missed this increased tax rate on small businesses in the Trump bill. That certainly scootched the mechanism for increasing the capital stock and employment that is supposed to operate in the Schlagenhauf et al model, whatever its details are. This makes it even less surprising indeed, that as I said might be the case, the TCJA may well led to or reinforced the flattening of employment growth from startups that seems to have been in place since 2016.

Why is it so difficult? Businesses invest when the investment makes them money. Tax policy doesn’t have much to do with it. Why would a business reinvest if the reinvestment doesn’t raise revenues? Why wouldn’t a business reinvest if the investment would raise revenues? And profits, assuming that it’s a reasonably well run business. The whole idea that the majority of businesses invest due to tax policy is completely baffling to me. Sure, some large, multi-national corporations manipulate revenues and accounting to take advantage of tax policy differences. But even they don’t spend money unless it’s to raise their profits. I’m amazed that this was ever even a debate. And I’m not anything but an outhouse economist with no credentials and less skill.

Nicely put. Remember when the Tea Partiers kept saying we needed to give tax breaks for the “Job Creators”. Not that the tax break would give any marginal incentive to create new jobs mind you. Just make sure good old Steve Jobs got even more money. After all he creates jobs in Asia.

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/1987/solow/biographical/

2slug had to remind me that the great Robert Solow has made it to his 96th birthday and hopefully soon will celebrate his 97th birthday. I also did not know he was born in Brooklyn!

Now I did know about his celebrated work from the late 1950’s on economic growth. Maybe Dr. Solow could take the time to explain the basics to Bruce “no relation to Robert” Hall. Of course he probably has better things to do besides trying to educate a dead tree.

You shouldn’t be that excited that Solow was born in Brooklyn solely on the basis that Bernie Sanders was born there. A lot of cerebral Jews were born in Brooklyn. Barney Frank was born in Bayonne New Jersey too, doesn’t mean I want to move there. Calm down.