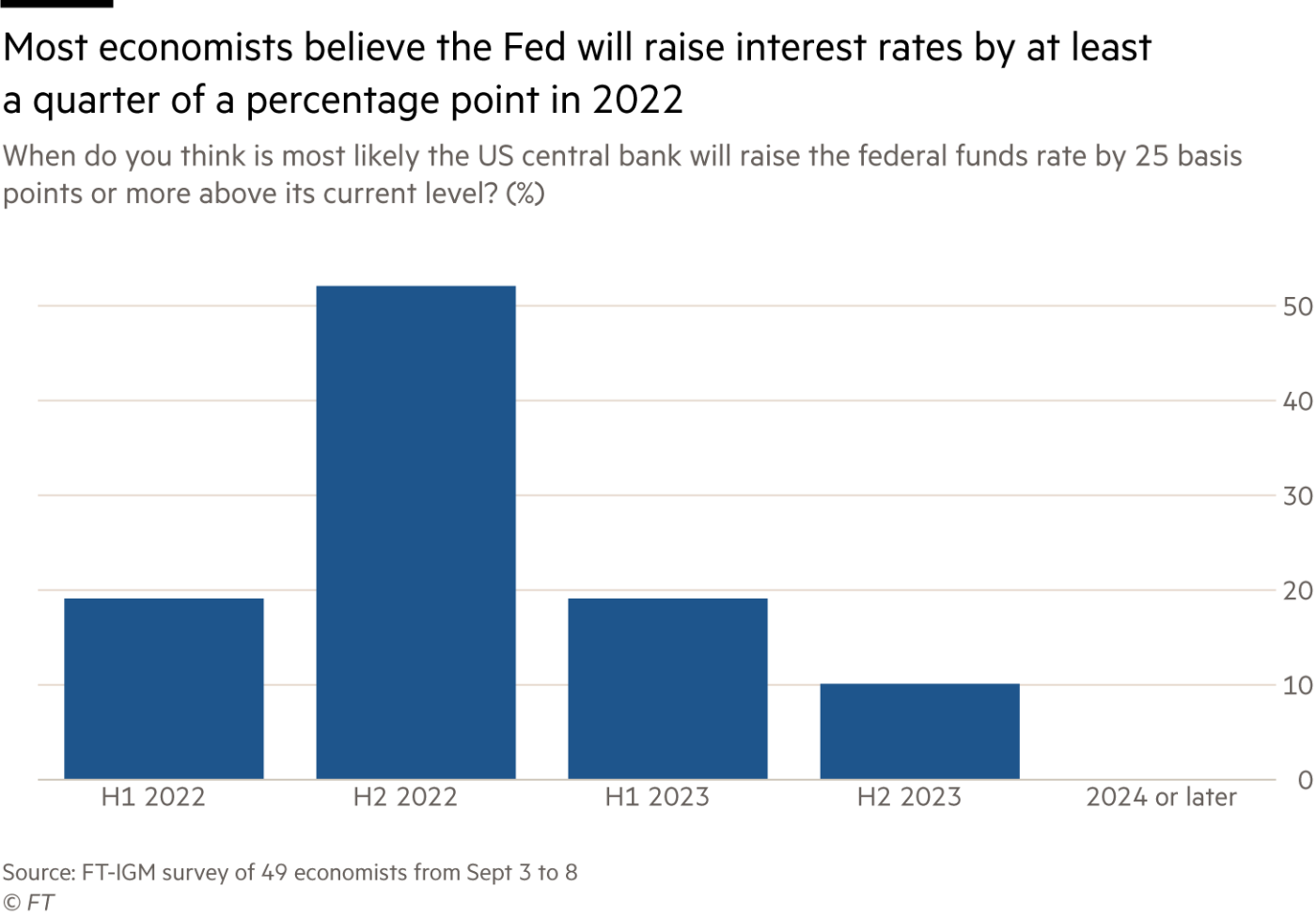

From FT Friday, “Economists predict US interest rate rise in 2022” (Colby Smith/Christine Zhang), discussion of results of the second FT-Chicago Booth IGM survey of macroeconomists:

The Federal Reserve will have to wind down its pandemic-era stimulus programme quickly and raise US interest rates in 2022 in response to higher inflation, according to a poll of leading academic economists for the Financial Times.

The latest survey conducted in partnership with the FT by the Initiative on Global Markets at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business suggests a much more aggressive approach to tightening monetary policy than the Fed’s most recent projections and market expectations indicate.

This is shown in the FT graphic.

The ungated survey can be found here. Some points that were of particular interest to me:

- GDP q4/q4 growth in 2021

- Core PCE 12 month inflation in 2021

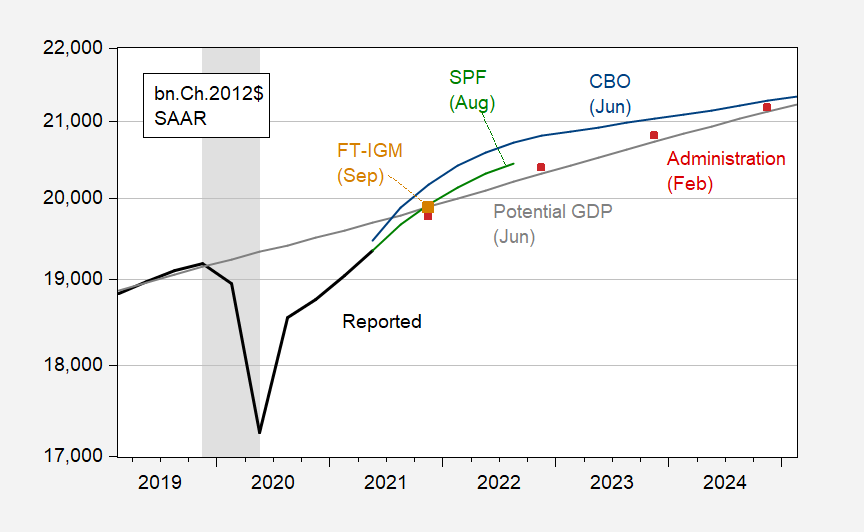

Median growth in the most recent survey is 6% q4/q4. This is shown in Figure 1, in comparison to other forecasts.

Figure 1: GDP as reported (black), CBO projection (blue line), Administration (red squares), Survey of Professional Forecasters (green), FT-IGM (tan large square), and potential GDP as estimated by CBO (gray line), all in bn. Ch2012$, SAAR, all on log scale. Dates pertain to date of forecast finalization. NBER recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA 2021Q2 2nd release, OMB FY’22 Budget, Philadelphia Fed SPF (May), and FT-IGM survey (September), CBO Economic Outlook (July), and author’s calculations.

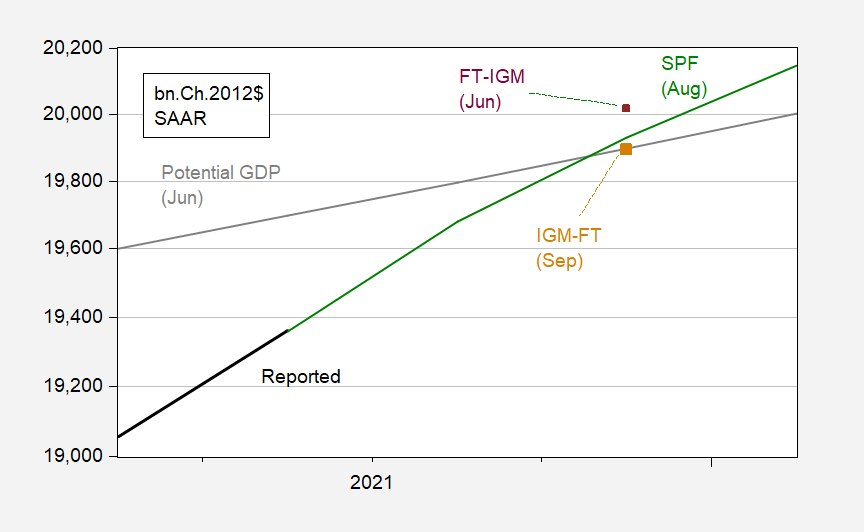

Since late June, forecasters on average have become less optimistic, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: GDP as reported (black), Survey of Professional Forecasters (green), FT-IGM September median forecast (tan large square), FT-IGM June median forecast (purple box), and potential GDP as estimated by CBO (gray line), all in bn. Ch2012$, SAAR, all on log scale. Source: BEA 2021Q2 2nd release, OMB FY’22 Budget, Philadelphia Fed SPF (August), and FT-IGM survey (September), CBO Economic Outlook (July), and author’s calculations.

Notice that the downward movement in forecasted Q4/Q4 growth — from 6.5% to 6%.

My point estimate was 5.4% (80%ile band was 5.1% to 5.7%), which is below the median response of 6% (90%ile was 6.4%, 10%ile was 4%). I was a bit surprised that I was so pessimistic relative to the overall group. After all, we already know Q1 and Q2 growth (SAAR): 6.3% and 6.6%; last week when I responded, the Atlanta Fed GDP nowcast (“GDPNow”) for Q3 was 3.7%. That means we have some idea of 3/4 of GDP growth (calculated q4/q4 — see how this differs from y/y on annual data). My 5% estimate for Q4 growth was a bit below the August Survey of Professional Forecasters median of 5.2%. To get the higher numbers, one has to believe both the Q3 outcome will be higher than the nowcast as of last week (and as of today’s revision, still 3.7%), and/or Q4 will come out higher than 5%.

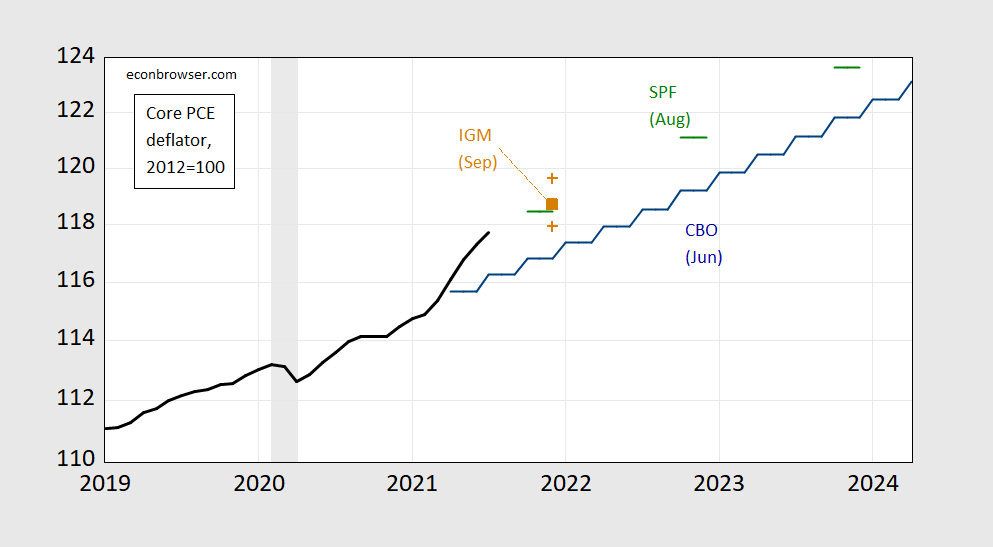

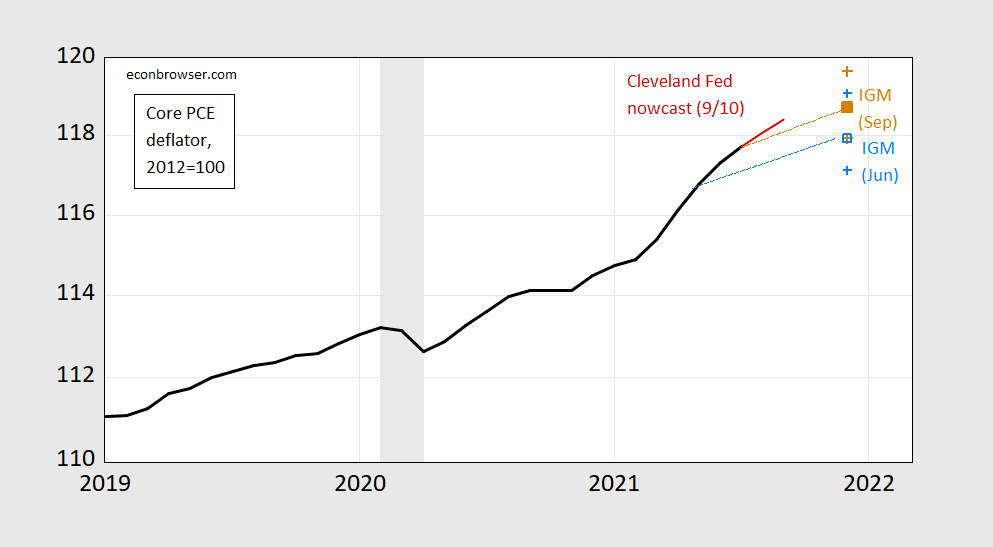

The other issue is inflation. The survey focused on core PCE. Here’s the FT-IGM forecast compared against others.

Figure 3: Core personal consumption expenditure deflator as reported (black line), CBO (blue line), Survey of Professional Forecasters (green line), FT-IGM (tan large square), FT-IGM, and 80%ile band (tan +), 2012=100, all on log scale. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA via FRED, Philadelphia Fed SPF (August), and FT-IGM survey (September), CBO Economic Outlook (July), NBER, and author’s calculations.

The FT-IGM median forecast is for a December 2021 price level slightly higher than that indicated by the August Survey of Professional Forecasters. The FT-IGM early September forecast (survey take 9/3-8) is also 0.7% higher (log terms) than the one taken late June (6/25-6/28, results here), reflecting the actual increase in reported PCE core deflator over the intervening two and half months (so 2 releases) and a slightly lower pace of inflation — the median Q4/Q4 forecasted growth rate rose from 3.0% to 3.7%. (I’m exactly at the median.)

Figure 4: Core personal consumption expenditure deflator as reported (black line), Cleveland Fed nowcast (red line), September FT-IGM median (tan large square), FT-IGM, and 80%ile band (tan +), June FT-IGM median (light blue open square), FT-IGM, and 80%ile band (light blue +), 2012=100, all on log scale. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA via FRED, Cleveland Fed (as of 9/10), and FT-IGM surveys (September, June), NBER, and author’s calculations.

The Cleveland Fed’s current nowcast are running above the implied average growth rate of the deflator, as implied by the September IFT-IGM survey. If the Cleveland Fed nowcasts prove accurate, then the FT-IGM median level will be hit if core PCE inflation rate averages 1.04% in October-December.

Interestingly, while the point forecast rises noticeably, the 80%ile bands corresponding to the two forecasts overlap substantially.

We’ll get some additional information on prices in Tuesday’s CPI release.

The ungated survey can be found here, Smith/Zhang FT article here.

Great post. Lots of stuff to digest. ZH, and I assume some other sources, have made much of shipping bottlenecks at oceanside ports maybe adding to inflation. Very curious to know how much (I mean is there a way to put this as a percentage part of inflation?? The “proportion of”?? )the typical economist in the IGM-FT survey included this in their thoughts or accounted for it in their forecasts?? Obviously the “isolated” part of inflation attributable to shipping bottlenecks has to be a higher proportion of the inflation than “in normal times”. I’m most curious Menzie’s thoughts on this, but happy to see anyone else’s thoughts on this particular facet of the inflation situation.

a rise in rates anywhere would be a good thing. It would mean things are getting back to ‘normal’

People, including policymakers, say things like this all the time, but it’s backward. Things getting back to normal leads to normalization of rates. With getting back to normal aready expected, here is no new information in the expectation of rate normalization.

The “news” in such cases is mostly in the extend to which priced-in market expectations are consistent with policymakers’ intensions.

A modest increase in interest rates seems prudent for next year. Of course Johnny Cochrane was calling for tighter monetary policy a decade ago and Stanford’s John B. Taylor has been screaming interest rates have been too low for too long for almost a generation. So what do the rest of us know?

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/10/opinion/transitory-inflation-covid-consumer-prices.html

September 10, 2021

Wonking Out: I’m still on Team Transitory

By Paul Krugman

Consumer prices have risen 4.4 percent over the past six months; that’s an annualized inflation rate of almost 9 percent, which puts us almost back into 1970s territory. And there are plenty of people out there proclaiming the return of stagflation.

But the people in a position to do something about it — above all, Jerome Powell, the chairman of the Federal Reserve — are fairly serene. They insist that we’re looking at only a transitory blip driven by the disruptions associated with America’s emergence from the pandemic. But are they right? How can we tell?

To answer those questions, we need to back up and ask what it means to say that inflation is transitory, anyway. And to do that, it helps to take a long view.

My sense is that many people believe that inflation wasn’t something that happened in America before the 1970s. But that isn’t true. Consumer price data go back more than a century, and there were several episodes of high inflation over that period. The ’70s weren’t even the peak:

https://static01.nyt.com/images/2021/09/10/opinion/krugman100921_1/krugman100921_1-articleLarge.png

Inflation over the long run.

What was the difference between the ’70s inflation and the inflationary spikes associated with World War I, the end of World War II or the Korean War? The answer is that those earlier bursts of inflation were easy come, easy go: The economy didn’t exactly return to price stability painlessly, but the recessions associated with disinflation were fairly brief. Ending the inflation of the ’70s, by contrast, involved a prolonged period of really high unemployment:

https://static01.nyt.com/images/2021/09/10/opinion/krugman100921_2/krugman100921_2-articleLarge.png

The cost of disinflation.

But what explained that difference? In the 1970s inflation became “embedded” in the economy. The people who were setting wages and prices did so with the expectation that there would be lots of inflation in the future. For example, companies were relatively willing to give their workers wage increases because they thought that their competitors would end up doing the same, so it wouldn’t put them at a competitive disadvantage.

The question is whether inflation is similarly becoming embedded now.

We used to have a fairly easy, rough-and-ready way to answer that question: the concept of core inflation. Back in the 1970s, the economist Robert Gordon suggested that we make a distinction between the price of commodities like oil and soybeans that fluctuate all the time and other prices that are adjusted less frequently. An inflation measure that excluded food and energy, he argued, would give us a much better indicator of underlying — i.e. embedded — inflation than the headline number.

The concept of core inflation has been one of the huge success stories of data-driven economic policy. Over the past 15 years we’ve seen several surges in consumer prices driven mainly by commodity prices and much hyperventilating, mainly on the political right, about the return of stagflation or even imminent hyperinflation. Remember when Paul Ryan, the Republican representative of Wisconsin at the time, accused Ben Bernanke, the former Fed chairman, of “debasing the dollar”?

The Fed, however, refused to back off from its easy-money policy, pointing to quiescent core inflation as a reason not to worry. And it was right:

https://static01.nyt.com/images/2021/09/10/opinion/krugman100921_3/krugman100921_3-articleLarge.png

Core for the win.

Unfortunately, at this point the traditional measure of core inflation doesn’t help much, because the pandemic has led to price spikes in unusual sectors like used cars and hotel rooms. So how can we find guidance?

The White House Council of Economic Advisers has been using a sort of “supercore” measure that excludes not just food and energy but also pandemic-affected sectors. This makes sense; in fact, I was arguing for such a measure months ago. But I’m aware that as one excludes more stuff from the Consumer Price Index, one exposes oneself to the charge that you’re saying that there’s no inflation if you ignore the prices that are rising.

Powell has pointed to a different measure: wage increases, which have been substantial in some of the pandemic-hit sectors but overall still seem moderate according to measures like the Atlanta Fed’s wage growth tracker:

https://static01.nyt.com/images/2021/09/10/opinion/krugman100921_4/krugman100921_4-articleLarge.png

Wage-price spiral? Not yet….

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=GJQU

January 30, 2020

Producer Commodities Price Index, 2020-2021

(Percent change)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=GJR1

January 30, 2020

Producer Commodities Price Index, 2020-2021

(Indexed to 2020)

[ Chinese authorities think that rising producer prices will prove transitory, but they are intervening sector by sector to directly limit price increases. ]

” but they are intervening sector by sector to directly limit price increases. ”

this is called central planning. we have had communist countries in the past attempt this economic model. it does not seem to work. both in a free market capitalist system and in a communist economic system, decisions will be made that are incorrect. the problem with the communist system, is when they take an action that is incorrect, rather than let the market work it out, the individuals who made the incorrect decision double down. central planning economies can react rather quickly to original disruptions in the economy, but by the nature of the people making decisions, they are much slower at fixing mistakes.

@ macroduck and whom it may concern

Something related to credit markets (property bonds, I guess to be specific):

https://www.ft.com/content/ae2bbe36-1e49-4a46-bc65-955bbf962e2a

https://www.ft.com/content/6d127e05-2208-4226-9cd1-ef2f7463cdf0

The article states there’s a very good chance Evergrande will suspend interest payments to lenders on September 21. Evergrande has some big players who have invested in them, including Allianz and Blackrock, and that an Evergrande default “would have spillover effects on global markets”.

On a very separate note FT also mentioned in other sections that China is releasing/selling some of their state oil reserves. They’ve done this before but they are making a public show of it this time, in an attempt to lower domestic oil prices and are also selling other state reserves for commodities and metals. So this is the old “central planning”, whatever, to tamp down domestic inflation.

Thanks, Moses.

Evergrande is an example of the occasional “let-burn situation” in China’s credit markets. (I’m betting you remember the original “let-burn” headline.)

China has a moral hazard problem in its lending markets. That leads to excess credit and sloppy due diligence. Letting Evergrande sink is consistent with the recent spectacle of slapping the rich around this in China, with the additional virtue of addressing a serious problem.

Baoshang Bank?? I pay closer attention to China than most people do, but if I’m to be honest I had to Google that one. I keep thinking in my head there was a large insurance company somewhere along the line that kinda-sorta failed, But I’m having a hard time remembering the name. Wasn’t there some point when commercial real estate hit a brick wall??~~maybe that’s what your referencing?? It’s so much to remember it seems.

Symbionese Liberation Army shoot-out, 1974: https://harpers.org/tag/symbionese-liberation-army-fire-and-police-shootout-1974/

The difference between the FT and SPF results reflects difference in participants, I suppose; these mables aren’t being drawn from the same jar.

The SPF jar includes academics and private forecasters. The FT jar contains only academics. Maybe that’s enough to explain the difference. If I ever have nothing else to do, a comparison of forecast accuracy between the two might be worth doing.

As to the likelihood of 5% annualized growth in Q4, that’s a heck of a hurdle. Christmas sales after a period of shipping problems aren’t likely to be great, and there’s also just a question of appetite. Do we really want more stuff after this?: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DPCERE1Q156NBEA

I’ve told Menzie that’s kind of an interesting question in my mind. I think I bend towards private forecasters when they are not talking their own book, as being better forecasters. But I think if you took the very most elite academics vs the most elite private forecasters, certainly the academics would give them a run for their money. And certainly if I got to handpick the academic forecasters, say top 20 vs top 20, me choosing the top 20 academic forecasters vs someone else choosing the top 20 private forecasters, I might even take that bet.

@ Macroduck

Jeffrey Gundlach would be a good example of that. I think he has one of the sharpest minds out there, the problem is when he’s trying to do a kind of propaganda or promotion for his and his customers’ bond holdings or trying to drum up more customer funds, then every word out of his mouth becomes suspect. I listen to him, but I always weigh it in my mind with “What is Gundlach saying here only to serve himself??”. You can get some jewels listening to Gundlach, but you always have to weigh it out.

http://www.news.cn/english/2021-09/09/c_1310178357.htm

September 9, 2021

China’s consumer inflation remains stable, factory prices climb

BEIJING — China’s consumer inflation remained generally stable in August, while factory-gate prices registered expansion largely due to increasing commodity prices, official data showed Thursday.

The country’s consumer price index (CPI), a main gauge of inflation, rose 0.8 percent year on year in August, data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) showed.

The figure was lower than the 1 percent year-on-year growth recorded in July.

The slower growth was partly driven by a drop in food prices, which declined 4.1 percent last month. In particular, the price of pork, a staple meat in China, slumped 44.9 percent from a year earlier.

On a monthly basis, CPI increased 0.1 percent, lower than the figure registered in July. Food prices increased 0.8 percent while non-food prices decreased 0.1 percent.

Due to sporadic outbreaks of COVID-19, heavy rains and high temperatures, prices of vegetables and eggs rose 8.6 percent and 8.4 percent, respectively.

Prices of industrial consumer goods dropped 0.2 percent mainly due to the decline of international crude oil prices, while prices of services remained unchanged as travel service consumption such as air tickets and hotel bookings was impacted due to COVID-19 prevention and control measures.

Senior NBS statistician Dong Lijuan said continued government efforts had led to ample supply in the consumer market and stable prices in August.

China has set its consumer inflation target at approximately 3 percent for the year 2021, according to this year’s government work report.

On the industrial side, China’s factory prices continued to pick up in August amid booming demand and rising prices of bulk commodities.

The producer price index (PPI), which measures costs for goods at the factory gate, went up 9.5 percent year on year in August, faster than the 9 percent year-on-year increase registered in July, the NBS said.

On a monthly basis, China’s PPI rose 0.7 percent in August, up 0.2 percentage points from July.

The faster expansion of PPI last month was due to price rises in coal, steel and chemicals, said senior NBS statistician Dong Lijuan.

Among the major sectors, coal mining and washing, chemical raw materials and products manufacturing, and ferrous metal smelting and processing were the main contributors to the increase in PPI inflation in August, according to Dong.

The widened scissors difference between CPI and PPI indicated that high raw material prices in recent months had not led to a rise in consumer goods prices, analysts said, noting government efforts to ensure stable supply and prices are still necessary.

NBS spokesperson Fu Linghui said commodity prices will remain high for some time amid global economic recovery, tight commodity supply in major raw material producing countries and fiscal stimulus and ample monetary liquidity in some major developed economies.

Commodity price hikes have raised production costs and squeezed profit margins for companies in the midstream and downstream of the industry chain, especially small and medium-sized enterprises.

To help cushion the stress from rising production costs due to high commodity prices, increased accounts receivable and epidemic and disaster impacts, the State Council executive meeting held on Sept. 1 pledged to increase the re-lending quota for small firms by another 300 billion yuan (about 46.44 billion U.S. dollars)….

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=Gb0g

January 30, 2018

Consumer Prices for China, United States, India, Japan and Germany, 2017-2021

(Percent change)