Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Justin-Damien Guénette (Senior Economist), Jongrim Ha (Senior Economist), M. Ayhan Kose (Chief Economist and Director) and Franziska Ohnsorge (Manager) from the World Bank’s Prospects Group. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this blog are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank, its Executive Directors, or the countries they represent.

In February 2022, global inflation rose to its highest level since 2008. Year-over-year inflation in advanced economies rose nearly ten-fold over the past year. That was before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine set commodity prices soaring. High and rising inflation has already been prompting many emerging market and developing-economy (EMDE) central banks to tighten monetary policy.

As the recent decision by the U.S. Federal Reserve shows, the economic fallout of the war in Ukraine is unlikely to derail announced plans of some major advanced-economy central banks to tighten monetary policies to rein in inflation. Should such policy tightening be faster than expected, it could lead to a sharp repricing of financial market risk in EMDEs and stifle economic recovery. To create space for monetary policy action and anchor medium-term inflation expectations, EMDE central banks need to bolster credibility including through transparent communications.

Inflation and policies

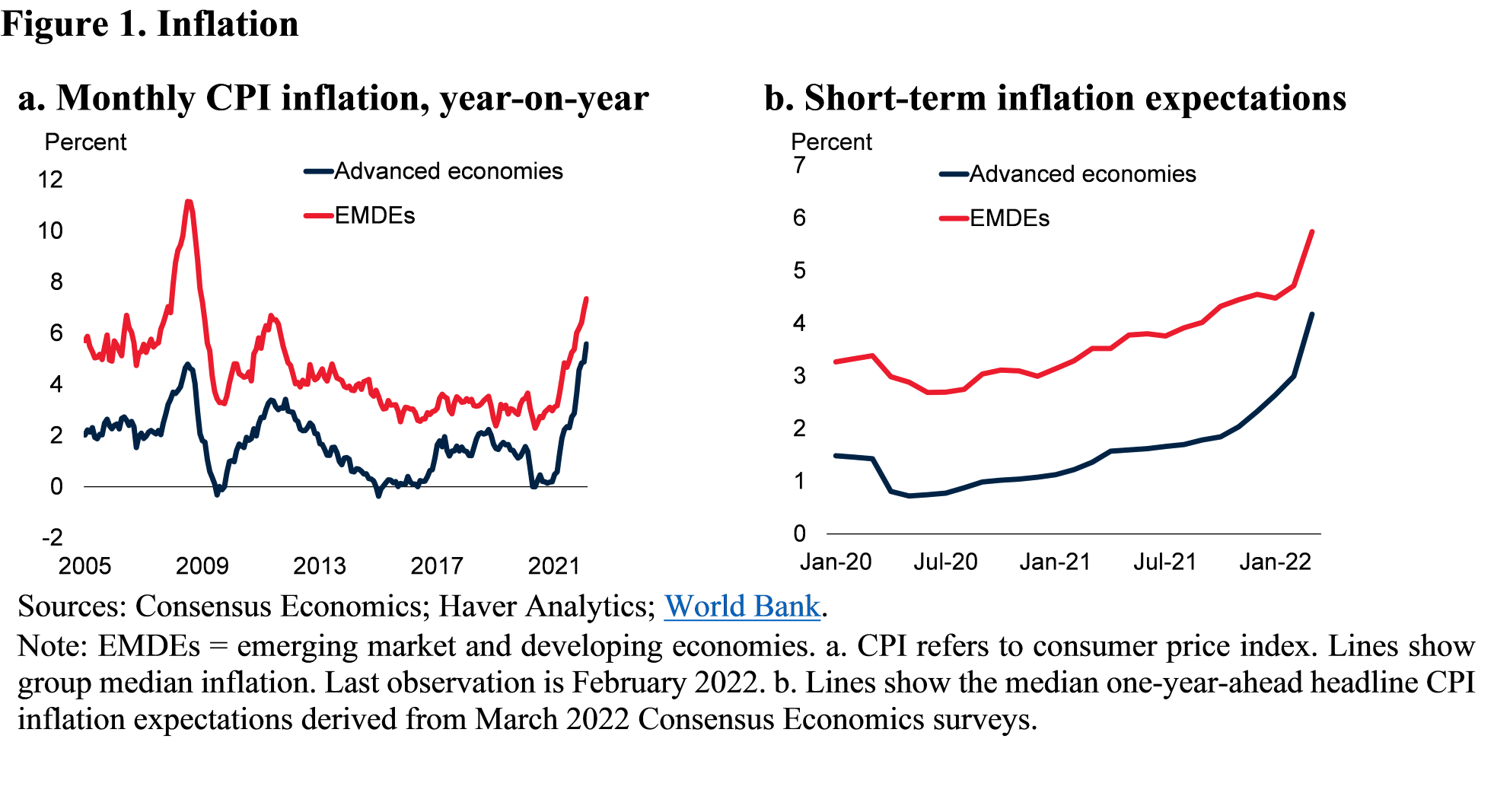

After declining in the first half of 2020, inflation in advanced economies and EMDEs accelerated on the back of the release of pent-up demand, persistent supply disruptions, and surging commodity prices (Figure 1a). The inflation rise has been broad-based: around nine tenths of the countries experienced an uptick in inflation last year. Rising inflationary pressures have pushed up near-term inflation expectations in many countries, in particular after the war in Ukraine (Figure 1b); in some economies, long-term inflation expectations have also crept up. In response to the rising prices and a steady uptick in inflation expectations, many EMDE central banks increased policy rates throughout 2021.

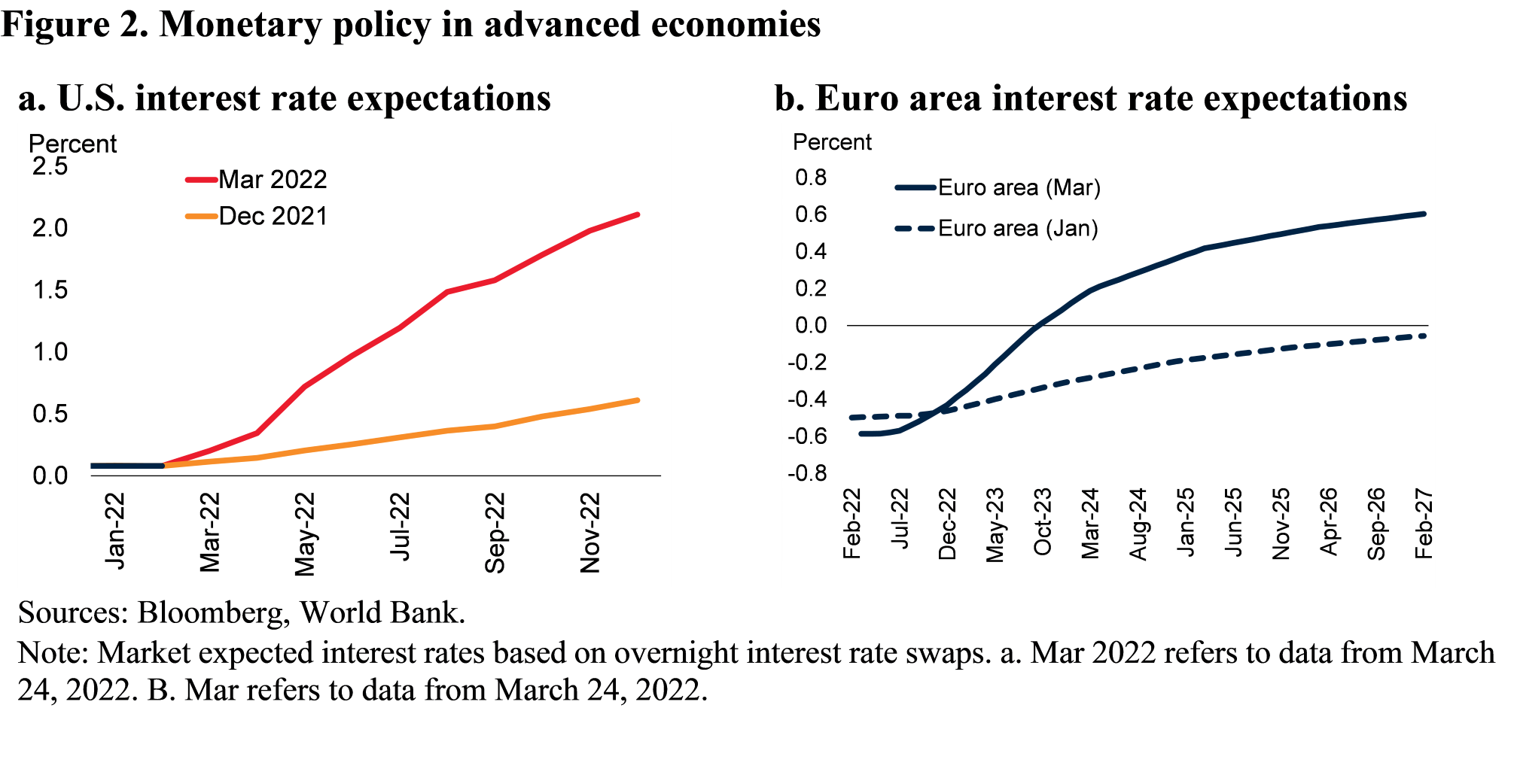

In advanced economies, central banks have so far reacted to the increase in inflationary pressures with a gradual response, tapering off unconventional support introduced during the pandemic, and (in some) raising policy rates. They have also communicated their intentions to raise rates further in the months ahead. On March 16, the U.S. Federal Reserve raised the fed funds rate by a widely-expected 25 basis points, and signaled a string of rate hikes by the end of 2022 (Figure 2).

Financial markets have significantly raised their expectations for the trajectory of policy rates at major central banks (Figures 2a and 2b). The prospective increase in policy rates has contributed to increased financial market volatility but has yet to trigger a material tightening of financial conditions across advanced economies.

Consequences of faster tightening

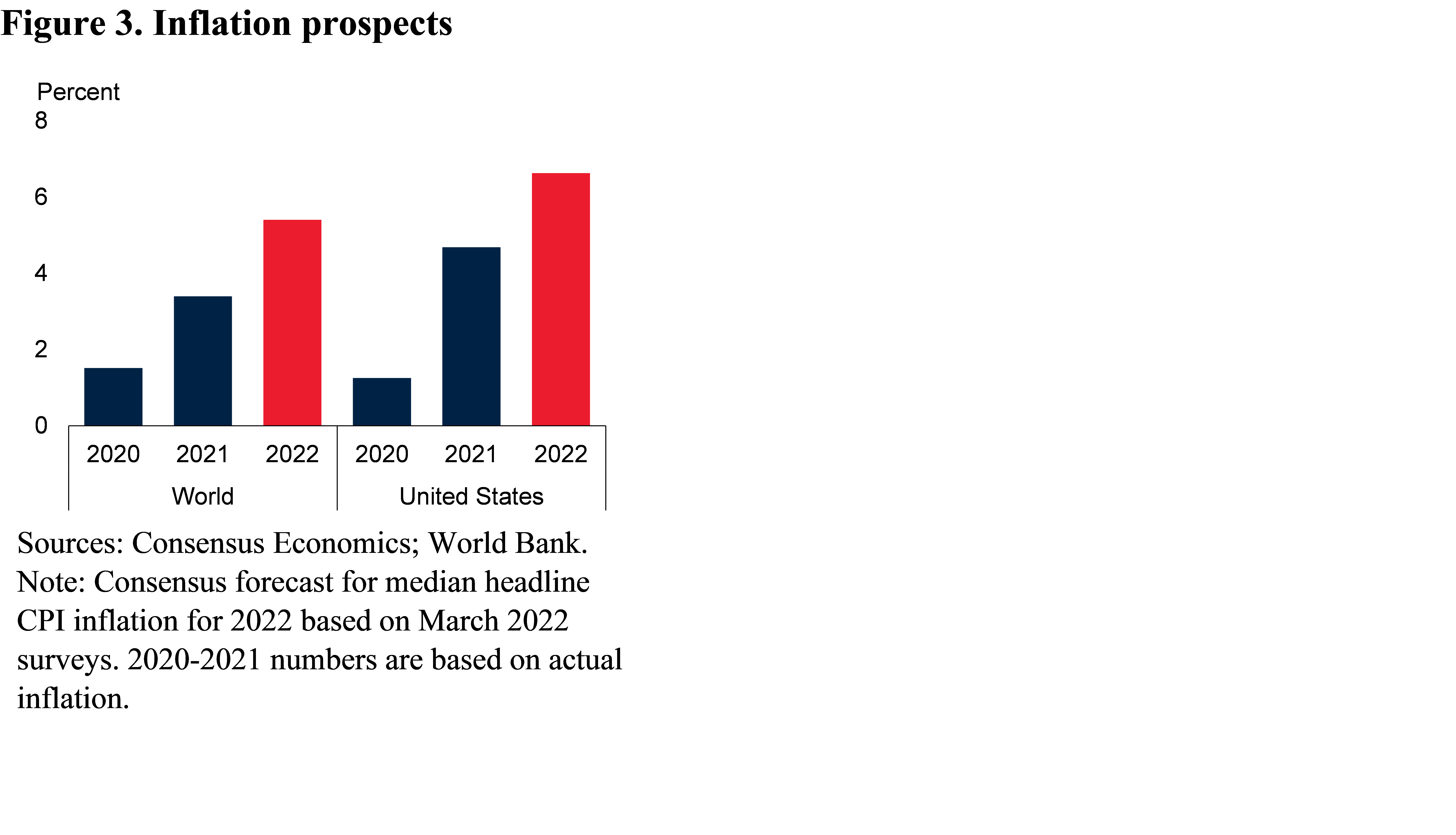

Global consumer price inflation is envisioned to peak later this year and then decline gradually, helped by well-anchored expectations in most economies (Figure 3). Easing inflation is in line with the anticipated global growth slowdown over 2022-23, from an exceptionally strong rebound in 2021. This global growth slowdown will be the steepest after any post-recession rebound over the past half-century and will be broad-based across advanced economies and EMDEs.

However, inflation is already above target in over nine tenths of advanced economies and two thirds of EMDEs that adopt inflation targeting. There is also a risk that inflationary pressures do not abate in the near term, and instead cause a steady rise in inflation expectations. For instance, if supply disruptions recur or commodity prices climb further—in particular due to the war in Ukraine—global inflation may remain high for a prolonged period or even rise further, pushing inflation well above target ranges for many countries. Although inflation data has yet to reflect the war in Ukraine, market-based inflation expectations have priced in additional inflationary pressures stemming from to the conflict.

If this risk materializes, advanced economy central banks may have no choice but rapidly increase policy rates. An upward shift in interest rate expectations in the United States could lead to a sharp repricing of risk by financial markets. The macroeconomic effects of an abrupt tightening of global financial conditions, as well as weaker consumer and business confidence, would compound the unwinding of global fiscal support and deepen the global slowdown underway. This could exacerbate already heightened macroeconomic vulnerabilities in EMDEs and trigger an even sharper slowdown in growth as negative spillovers via confidence, trade, and commodity price channels would reduce private sector activity.

These countries would experience capital outflows in response to heightened investor risk aversion, leading to currency depreciation, which in turn would worsen debt burdens and boost inflation. Foreign currency-denominated debt accounted for one-half or more of government debt in one-half of EMDEs in 2020. Even when not denominated in foreign currency, government and private debt at multi-decade highs makes these economies vulnerable to rising borrowing cost and rollover risk. Domestic credit spreads would widen, sparking a rise in defaults, especially in those countries with pre-existing balance sheet vulnerabilities. Increased debt servicing costs amid heightened rollover risks would force governments in many EMDEs, particularly in countries with limited fiscal space, to reduce public spending and delay investment projects. EMDEs would experience renewed downturns, with growth falling significantly this year.

Policies: Need for calibration, credibility, and communication

While EMDE policymakers have limited impact on the design of monetary policies in advanced economies, they can usefully focus on calibration, credibility, and communication of their own policies. Specifically, mitigating adverse effects of the tightening cycle requires careful calibration, credible formulation, and clear communication of policies. This approach can go a long way in making EMDEs more resilient to sudden shifts in global financial markets.

For monetary policy, calibrating policy levers to get ahead of inflation without stifling the recovery will be key. For EMDEs, communicating monetary policy decisions clearly, leveraging credible monetary frameworks, and safeguarding central bank independence will also be critical to manage the cycle. On the financial side, policymakers must work to rebuild reserve buffers and realign prudential policy—including capital and liquidity buffers. In addition, they will need to bolster risk monitoring and enhance bankruptcy regimes.

With respect to fiscal policy, the message is much the same. The pace and magnitude of withdrawal of fiscal support must be finely calibrated and closely aligned with credible medium-term fiscal plans. Moreover, policymakers need to address investor concerns about long-run debt sustainability by strengthening fiscal frameworks, enhancing debt transparency, upgrading debt management functions, and improving the revenue and expenditure sides of the government balance sheet.

This post written by Justin-Damien Guénette, Jongrim Ha, M. Ayhan Kose and Franziska Ohnsorge.

https://conversableeconomist.com/2022/03/29/interview-with-lawrence-summers-inflation-and-the-economy/

March 29, 2022

Interview with Lawrence Summers: Inflation and the Economy

It’s not common. But every now and then, a prominent economist will make a strong near-term prediction that flies in the face of both mainstream wisdom and their known political loyalties. Lawrence Summers did that back in March 2021. As background, Summers was Secretary of the Treasury for a couple of years during the Clinton administration and head of the National Economic Council for a couple of years in the Obama administration. Moreover, he is someone who has been arguing for some years that the US economy needs a bigger boost in demand from the federal government to counter the forces of “secular stagnation.” * ** Thus, you might assume that Summers would have been a supporter of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, backed by the Biden administration and signed into law in March 2021.

Instead, Summers almost immediately warned that this rescue package, when added to the previous pandemic relief legislation, would increase demand in the economy in a way that would be likely to set off a wave of inflation. There was some historical irony here. Back during the early years of the Obama administration when the US economy was struggling to rebound from the Great Recession, Summers was a prominent supporter of increased federal spending at that time–often warning that the problem was likely to be doing too little rather than doing too much. Some opponents of the 2009 legislation predicted that it would cause inflation, but it didn’t happen. Now in March 2021, Summers was on the “it’s too big and will cause inflation” side of the fence.

Jump forward a year to March 2022, and Summers looks prescient. Yes, one can always argue that someone made a correct prediction, but that they did so for the wrong reasons, and events just evolved so that their prediction luckily turned out to be true. And one can also argue that all those making the wrong prediction about inflation back in spring 2021 were actually correct, but events just evolved in an unexpected way so that just by bad luck they turned out to be wrong. But maybe, just maybe, those who were wrong have something to learn from those who were right….

* https://conversableeconomist.com/2015/12/28/secular-stagnation-an-update/

** https://conversableeconomist.com/2013/12/12/secular-stagnation-back-to-alvin-hansen/

— Timothy Taylor

Roubini: “Putting aside the war’s profound long-term geopolitical ramifications, the immediate economic impact has come in the form of higher energy, food, and industrial metal prices. This, together with additional disruptions to global supply chains, has exacerbated the stagflationary conditions that emerged during the pandemic.” https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/stagflationary-environment-putins-war-no-optimal-policy-response-by-nouriel-roubini-and-brunello-rosa-2022-03?barrier=accesspaylog

Michael Hudson considers the long term consequences of Washington’s attempt to sanction those who resist its diktats: ““Dollar Hegemony Ended Last Wednesday””

https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2022/03/dollar-hegemony-ended-last-wednesday-michael-hudson-interviewed-by-margaret-flowers-on-clearing-the-fog.html

Is the free lunch starting to come to an end?

Let’s put ALL our cards on the table now. YOU feel sorry for Russians, while Russian soldiers are murdering Ukrainians in droves??? Spell it out and take a side or STFU Got it?? I don’t want to hear one word more from you until you tell us which side is worse/

I understand, after the many, many times that you have gotten economics wrong, that you would want to avoid saying anything that could be construed as a point. Congratulations for recognizing you have noying to add. That’s an improvement.

Nouriel is very good at summarizing and at recognizing policy dilemmas. So good for you for linking to him.

Michael Hudson? An idiosyncratic Marxist with a grudge. Not that he has nothing to say, but he slices the baloney wiy an qgenda in every cut. There are other ways to describe the same stuff which don’t involve so much finger wagging.

Your final question? Kinda like rsm, hiding behind questions when one lacks the knowledge (or courage) to make a statement. So I’m glad you haven’t made your usual mess, but you still have a ways to go.

you give too much credit to roubini. I used to listen to him, once upon a time. but over time, you realize he is not really insightful, but a broken clock. he has called for 10 financial crashes in the past decade. he got one right. but that is simply because he predicted the same crash during the previous two decades.

Rbaffling,

Nouriel has built himself a niche in public which doesn’t alway play well with those who have a full grasp of events. It’s a personna thing. His professional work is not usually like that. The guy knows his stuff.

Full disclosure – worked with him for a while on his behind-the-paywall stuff.

I don’t doubt that he knows his stuff. but he lets his confidence override his knowledge. at least when interacting with the public. like I said, at one time I would listen to what he had to say. but over the years, I have found that what he has to say is more about how he feels the world should operate, not how the world actually operates. too often, the message is that the world is simply wrong. I don’t find that type of information helpful, as an investor. every time I listen to him, I walk away thinking my best course of action is to stuff all my cash under the mattress. just not that helpful, imo. I understand the contrarian view, as I am more susceptible to that viewpoint myself. but I also understand, over a 10 year window, the bull beats the bear. every single time. roubini is great at telling you when and how to get out of the market. he just can’t tell you when and how to get back into the market.

JohnH,

Sorry, but your Hudson link is just plain nuts. For those not wanting to waste their time he argues that this invasion of Ukraine by Russia is really a war by the US on Germany. Really? Really? Do not think so. He makes this claim about “last Wednesday” that has you all excited.. But it looks like what has him making this claim is the Putin demand for payment in rubles for gas. But that demand has since collapsed, a fact you seem not to have picked up on yet.

Sorry, your claim is just vacuous bs.

“Is the free lunch starting to come to an end?”

It is time to end this war but your constant blaming of Biden needs to come to an end. This is Putin’s War and you are his chief spokesperson. Disgusting.

“Like the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia’s war in Ukraine has contributed to the stagflationary pressures in the United States and other advanced economies.”

I guess you skipped their very first sentence as they clearly see this as Putin’s War. But not JohnH – Putin’s favorite poodle.

The observation that growth will decelerate rapidly relative to prior expansions means different things to different economies. The U.S. has recovered from he Covid recession remarkably rapidly. Many other economies have done less well. So a rapid slowing in the U.S. is a reflection of limited unused capacity, while in many places it is simply bad news. The fact that U.S. monetary and fiscal policy will contribute to slower growth everywhere despite available capacity outside the U.S. is par for the course, but sad.

Both Fed tightening and increasing economic and policy risk are likely to mean currency weakness for developing economies, which could make their Inflation problems worse despite slowing growth and (one hopes) easing inflation in the rest of the world. Same as it ever was.

Commodity producers, which have done best in the inflation run-up, may have a period of grace due to sanctions on Russia, but slower growth will eventually end their party.

Large debt accumulation during the period of low rates and the pandemic will require restructuring in many economiss. It’s not clear the world is organized in a way to facilitate restructuring. The Paris Club has folded its tent and China was never a member.

The combination of the war in Ukraine with reductions of oil and food exports from Russia and Ukraine as well as the reappearance of lockdowns in China due to the pandemic means that the world is facing further supply chain problems that will aggravate global inflation for some time to come. The question for the US is how much higher has inflation been here from our more expansive demand side stimulus policies. As it is we have a pretty good idea what that amounts to, probably about an extra two percent. It is there in that comparison of US versus world inflation expectations, which is about the same in the difference in current inflation between the US and the eurozone, which is also about two percent.

One might consider inflation’s skewing of numbers “the illusion of prosperity”. Real wages for the were flat during the Obama administration and rose during the first three years of the Trump administration… all during a period of very low inflation. 2020 on this graph is an anomaly because it reflects (excessive?) temporary government subsidies. 2021 reflects the removal of those subsidies.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/LES1252881600Q

The question is how much will real wages fall during this period of rising prices?

https://www.bls.gov/news.release/realer.nr0.htm

Of course, for those whose income is generally fixed, there is no illusion of prosperity.

For small businesses, inflation requires a tradeoff between raising prices and losing customers. This can require staff layoffs. Not a good indicator of prosperity.

So the question before the house is how much “fine tuning” can the Fed do with regard to interest rates during a period of nearly 8% inflation? Something or someone is going to pay the price of inflation the longer it continues unabated. Perhaps it will just fix itself?

Households are just going to have to accept higher prices for as long as the Great Inflation lasts. Alas, there’s a good chance that a recession will end it: Any time inflation has been this high and unemployment this low in the past seven decades, one has followed within a year or two. Six out of the last seven downturns were preceded by spikes in the price of gasoline. In four, geopolitical crises were a proximate cause. If an economic collapse comes soon, rising prices might not seem so bad.

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/03/inflation-federal-reserve-recession/627079/

“Real wages for the were flat during the Obama administration and rose during the first three years of the Trump administration”

Even a blind squirrel could see your line here is a complete misrepresentation. But that’s fine as the rest of your comment was your usual word salad gibberish. If you are playing Steno Sue for Kelly Anne Conway again – you might want to ask her to sober up before writing such meaningless junk.

I saw an estimate that the typical US household will lose $5,200 to 2022 inflation.

CNBC survey of investors says, [Translation] “Do not underestimate the Fed’s ability to f@#$ things up.”

Apparently, Biden’s handlers plan to continue to pound the US economy until the rubble bounces. [I will repeat this comment with facts and figures in September.]

CNBC? You rely on those pompous morons for economic analysis? Now we get why your comments are so often so dumb!

“ The question is how much will real wages fall during this period of rising prices?”

And the second question is how much they will fall during the subsequent tightening and contraction?

And, heads I win, tails you lose, income and wealth will continue their inexorable shift to the wealthy after a momentary pause.

Progress! You have finally realized that being a gold bug can be a bad idea.

Wow Brucie – your total misrepresentation has been called out in a new post. So you have to answer this basic question before you next chirping. Are you really s blind squirrel or do just lie 24/7?