Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Filippo Natoli and Fabrizio Venditti of the Directorate General for Economics, Statistics and Research of the Bank of Italy. The views presented in this note represent those of the author and not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Italy.

A negative reading for the advance estimate of US GDP growth in q2 surprised private forecasters, contributing to recession talks. By using a standard forecasting model, we show that, when accounting for the high level of CPI inflation and tight labor markets, an incoming recession appeared to be extremely likely even one month ago, both in the United States and the United Kingdom.

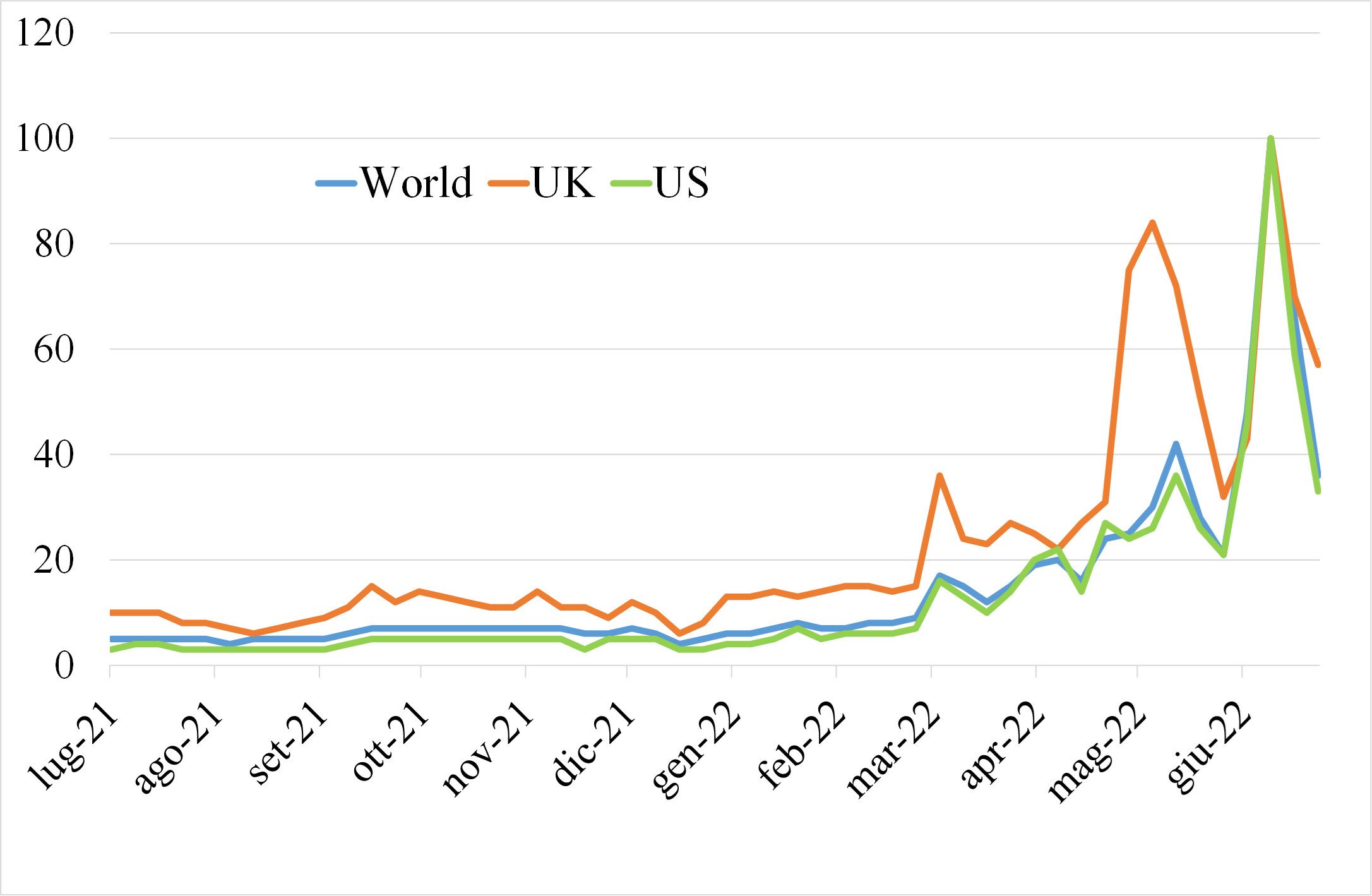

The second quarter of 2022 has witnessed a sharp deterioration in the global business cycle momentum as global trade remains stifled by persistent supply bottlenecks, commodity prices are bolstered by the war in Ukraine and high inflation keeps eroding consumer purchasing power. Meanwhile financial conditions have tightened considerably, as central banks reacted aggressively to stubborn inflationary pressures. Against this backdrop, the US economy has recorded a second consecutive negative GDP print, after the fall of economic activity in Q1. The prospects for other advanced economies appear equally worrisome, especially for energy importers, whose terms of trade have rapidly deteriorated following the invasion of Ukraine. Forecasters have factored in these headwinds and have marked down their expectations for global growth in 2022 and 2023 (see, e.g., IMF) and the question seems to be when rather than if a recession is going to occur: the search of the word “recession” on Google has flared up since last March (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Google search intensity of the word “recession”

(number of hits ranked between 0 and 100 over the considered period). Source: Google trends

In recent work (Natoli and Venditti, 2022), we contribute to this debate by jointly evaluating the relevance of financial and macroeconomic factors in anticipating recessions in the United States and in the United Kingdom since the late 1990s. In our analysis we rely on the standard probit forecasting framework pioneered by Estrella and Hardouvelis (1991),

where the dependent variable is a dummy equal to one (zero) if the economy is (is not) in a recession at time t + h, h is the forecast horizon, x is the set of regressors, F(.) is the standard normal cumulative distribution function and is a normally distributed error.

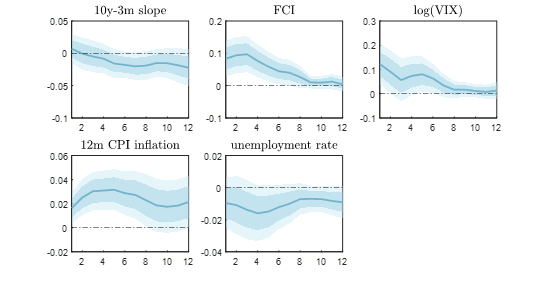

The standard specification in the literature, which we take as a baseline, considers the slope of the government bond yield curve – the difference between the 10-year vs. 3-month yield – as a unique predictor. The ability of this minimalistic model to predict recessions, however, has been recently questioned in the literature (Karnizova and Li, 2014; Ercolani and Natoli, 2020; Kiley, 2022, among others). We therefore start by adding to the baseline specification indicators of market stress – financial conditions and stock market volatility, according to the view that the slope of the yield curve alone might be unable to fully capture deteriorating financing conditions leading to a crisis. A Financial Condition Index (FCI) is constructed as an unweighted average of 10-year yields, monthly stock returns and corporate bond yield spreads, in the spirit of Arrigoni et al. (2022), while stock market volatility is captured by the VIX. In a third specification we also add two variables summarizing the macroeconomic environment – CPI inflation and the unemployment rate. Figure 2 shows coefficient estimates for the US over different forecasting horizons (1 to 12). They confirm that financial indicators and macroeconomic conditions provide additional predicting power. In particular they show that periods of (i) flat yield curves (ii) tight financial conditions (iii) high financial market uncertainty (iv) high inflation and (v) low unemployment (broadly resembling the current economic environment) were likely to be followed by a recession. Estimates for the UK are very similar.

Figure 2: Average marginal effects, US model

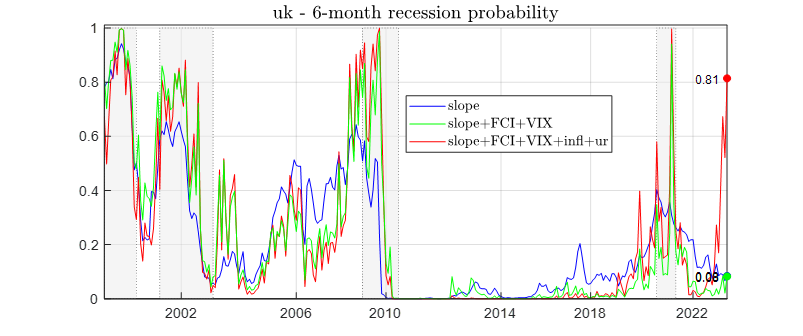

When specifications based on the slope of the yield curve are enriched by key financial and macroeconomic indicators, forecasting performance improves considerably and, in the current environment, the probability of an incoming recession jumps to values very close to 1. Figure 3 shows the time series of the predicted recession probability (6-month ahead) of the model that relies only on the slope of the yield curve (blue lines), of the intermediate specification that includes the VIX and FCI (green line) and of the full model that also introduces inflation and unemployment (red line). According to standard measures of fit, this last model is the one that performs best. All models are estimated with data going from January 1998 up to May 2022 – i.e., already available around mid-June. It turns out that, historically, financial conditions played a more important role than inflation and unemployment in predicting the recessions of the early 2000s; also, they were very tight before the pandemic shock that eventually toppled the global economy in 2020. In the case of the Great Recession in 2008 both financial and real factors played a role. At the current juncture, on the other hand, the strongest recession signals are coming from record high inflation and tight labor markets, in line with what is found in Domash and Summers (2022). An interesting observation is that the sample period includes years of anchored inflation expectations and credible monetary policy: our results indicate that, even in such environment, an aggressive monetary response – sufficiently aggressive as to generate a recession – would be needed to tame inflation. All in all, our results indicate that, at the current juncture, a soft landing – engineering disinflation without provoking a recession – is very unlikely. The actual combination of hot labor markets, high inflation and tight financial conditions has been typically followed by a recession.

Figure 3: Recession probabilities six months ahead, time series

Panel A

Panel B

Note: economy-specific recession bands are based on the OECD recession indicators

Source: Natoli, F. and Venditti F. (2022). The role of financial and macroeconomic conditions in forecasting recession (July 29, 2022). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract= 4176581

This post written by Filippo Natoli and Fabrizio Venditti.

“All in all, our results indicate that, at the current juncture, a soft landing – engineering disinflation without provoking a recession – is very unlikely. The actual combination of hot labor markets, high inflation and tight financial conditions has been typically followed by a recession.”

This sounds a lot like the latest from the old man Larry Summers. I have been calling this our Volcker moment. Of course a young Larry Summers joined Paul Krugman to go to work for Martin Feldstein at the CEA to clean up that 1982 mess. Old Paul Krugman seems to be more hopeful than this former colleague at the Reagan CEA.

I still don’t know what to think about all of this, but one thing I’ve been thinking about is the flexibility of the US labor market. Covid showed just how much more flexible the US is compared to, say, Europe. Big downsides when a shock hits (Q2 of 2020) but then a big rebound. I’m thinking this could help cushion any recession. Remember, 2008 was about a fragile financial system and lots of bad debt. That might explain the long recovery. We appear to have neither of those problems. If there is a Fed recession, we might bounce back quickly like we did since 2020.

But I hasten to mention that today’s jobs figures (500k+ new jobs, 3.5% unempl) give more credence to the analysis in the post. Very high inflation, very tight job market, very quickly tightening financial conditions. With the job market response being so mute so far (lags and all) we should expect a lot more tightening.

wti volatility

opec+ hesitation

suggest macro slowdown

today’s eia shows crude from strat petrol reserve served to keep comm’l stock from a draw down

contrary to hopes spr draw was about 4.5 million on the week of 29 jul

more than expected?

By focusing on Fed rate hikes and recent recessions, forecasters are completely missing the period 1945-55 which featured (1) tight labor markets, (2) two episodes of very high inflation, (3) low interest rates, and (4) the Fed completely sitting on its hands.

And yet there were two recessions.

I submit that the 2020-21 Boom is most like those two periods, and that is where academics should be focusing. (Hint: what happened to house prices right after World War 2?)

http://www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data.htm

January 30, 2018

Real Home Price Index, 1940-1959

1940 ( 81.73) *

1941 ( 73.82)

1942 ( 68.50)

1943 ( 70.92)

1944 ( 80.31)

1945 ( 87.75) Truman

1946 ( 106.51)

1947 ( 109.33)

1948 ( 101.22)

1949 ( 100.05)

1950 ( 105.89)

1951 ( 103.90)

1952 ( 103.97)

1953 ( 114.57) Eisenhower

1954 ( 114.79)

1955 ( 115.62)

1956 ( 114.29)

1957 ( 113.67)

1958 ( 112.22)

1959 ( 111.10)

* 1890 = 100

— Robert Shiller

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=QJHY

January 30, 2018

Case-Shiller National Home Price Index / Consumer Price Index, 1992-2022

(Indexed to 1992)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=R4BT

January 30, 2018

Case-Shiller National Home Price Index / Consumer Price Index, 2007-2022

(Indexed to 2007)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=SqY0

January 30, 2018

Industrial Production, 1940-1959

(Percent change)

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/senate-to-vote-on-finland-sweden-nato-membership/ar-AA10h7PD

Aug. 3 (UPI) — The Senate is expected to vote Wednesday afternoon on whether or not to ratify Finland and Sweden’s applications to join NATO. Majority Leader Chuck Schumer confirmed that the vote would take place. In mid July, House lawmakers overwhelmingly passed legislation in support of both Nordic countries joining the NATO defensive military alliance. The bill passed the House in a 394-18 vote with all those casting ballots against it coming from the Republican Party. The legislation also urged all NATO members to do the same.

18 House Republicans who work for Putin. I wonder how many Putin pet poodles are in the Senate.

Interesting, but I’m not convinced. The time frame is too short – 3 US recessions doesn’t provide enough of a sample size IMO. Also, the disconnect between slope+FCI+VIX and slope+FCI+VIX+infl+ur is definitely an aberration, though again not enough data to make a true judgement on how much of an aberration there is. I’d be curious to see what the data showed going back to the mid-70’s and including the ’80-81 recession.

It appears tha Natoli and Venditti use OECD recession timing indicators, rather than NBER. That makes sense in comparing the UK and the U.S. It’s probably worth noting, though, that OECD and NBER definitions don’t always matchup:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=SqST

For some time, a number of forecasters and forecasting tools have suggested an elevated risk of recession starting in Q2 to Q4 of 2023. This model anticipated recession a few months earlier.

Common wisdom has it that the labor market lags, but common wisdom misses a good bit, as this model demonstrates. A strong labor market, for one thing, tends to pull durables and housing consumption forward. I’m not surprised that the jobless rate is predictive, but I am surprised at the relatively small and steady coefficient on the jobless rate, compared to financial variables.

This model signals recession risk ahead of the Covid pandemic. Then, the Fed responded to financial stress by ending normalization of monetary policy and then by easing a bit. Not so this time.

Low unemployment being a predictor of recessions is a bit counterintuitive. How does one distinguish a simple cyclical mean reversion effect (i.e. the lower unemployment goes, the more likely it will rise back to average values) from an actual causal effect. How much does it matter for their model? If one simply wanted to include mean reversion effects, you could also include variables like “time since last recession” and “realGDP/potential GDP”, but does this really tell us anything about causality?

Forecaster Robert Dieli has a very successful simple forecasting tool that relies on this “counterintuitive” fact. It essentially compares the Phillips curve and the yield curve. He subtracts the unemployment rate from the inflation rate, and the Fed funds rate from the 10 year bond. He then adds the two results together. If I recall correctly, when the net result is less than 200 basis points, it results in a recession watch (note my memory may be off here). Essentially, his model forecasts that when the unemployment rate gets “too low” compared with the inflation rate, the Fed will begin tightening, and keep doing it until something breaks.

F: “Low unemployment being a predictor of recessions is a bit counterintuitive. How does one distinguish a simple cyclical mean reversion effect (i.e. the lower unemployment goes, the more likely it will rise back to average values) from an actual causal effect.”

Don’t confuse predictive with causal. Low unemployment is simply a prompt for the Federal Reserve to show the proles their proper place when they get too uppity. Low unemployment doesn’t cause the recession, the Fed’s reaction to low unemployment causes the recession. Powell has been talking obsessively about the “two-job-openings-for-every-unemployed-worker” myth for months. He is determined to remedy that.

Europe will go down hard.