That’s the title of a recent SF Fed Economic Letter, by Reuven Glick, Sylvain Leduc, and Mollie Pepper.

Households are currently expecting inflation to run high in the short run but to remain muted over the more distant future. Given this divergence, what role do short-run and long-run household inflation expectations play in determining what workers expect for future wages? Data show that wage inflation is sensitive to movements in household short-run inflation expectations but not to those over longer horizons. This points to an upside risk for inflation, as workers negotiate higher wages that businesses could pass on to consumers by raising prices.

This is a remarkably clear-headed analytical way of thinking about whether wages and how wages will respond to inflation developments and determinants. It’s also a reminder that the original paper by A.W. Phillips was about nominal wages, or “The Relation Between Unemployment and the Rate of Change of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861–1957” in Economica (1958).

Glick et al. estimate the Phillips curve using

“…quarterly data from the second quarter of 1980 to the first quarter of 2022. We measure wages using the wages and salaries component of the employment cost index compiled by the BEA, with data beginning in the first quarter of 1980. This measure accounts for changes in the composition of the workforce, which could impact wage growth separately from the wage Phillips curve. Inflation rates in wages and core prices are measured as (log) changes over each quarter at an annual rate.”

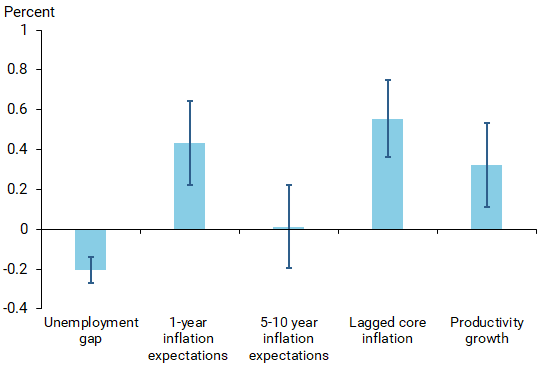

and obtain the following estimated effects on wage inflation of 1% change in variables (Figure 3 from the Letter):

Figure 3: Effects on wage inflation of 1% change in variables from Glick et al. (2022).

Interestingly, the original Phillips curve paper is still useful reading; while it does not directly incorporate long term inflation expectations, nor composition of labor demand effects, it does note the importance of actual and expected inflation (as well as productivity).

The authors conclude:

the increase in short-run expectations since last spring point to an important upside risk to inflation, as workers negotiate higher wages that businesses could pass on to consumers in the form of higher prices. By reducing overall demand, the ongoing monetary policy tightening will help reduce the probability that this risk materializes.

That being said, the productivity numbers that came out after Glick et al.’s analysis, in the costs and productivity release, are surely going to complicate the outlook for managing inflation, even if we account for likely revisions in productivity growth (see e.g., Furman and Powell, 2022).

(NB: If you don’t like the use of natural logs — e.g. here and here — avert your eyes from this paper, and the Phillips paper! This means Steven Kopits, James Sexton, etc.)

Companies have more than enough margins to absorb labor cost increases. They used the supply chain problems to jack up prices and harvest obscene profits in the past 2 years. As long as China doesn’t screw up the supply chains again (with their zero Covid absurdities) my guess is that the competition for consumer dollars will keep price increases to a minimum.

“Companies have more than enough margins to absorb labor cost increases.”

While this is true – do you believe companies with market power are going to readily accept a normal return to capital? Now if we enforced anti-trust laws, then maybe they would have to.

Companies will jack the prices as far up as the market will allow. That is regardless of whether they can lower labor cost or are forced to accept higher labor costs. It appears that a number of companies (Target, Walmart, etc.) have overstocked and are trying to unload merchandize (have lost pricing power). My guess is that Biden is a lot more likely to enforce anti-trust laws than Trump – but not as far as I would. Market forces will work better than they did last year as we sort out supply chains and people moderate discretionary spending. But I agree that these laws will work less than they should (and would if we had strong anti-trust enforcement).

“Companies will jack the prices as far up as the market will allow. That is regardless of whether they can lower labor cost or are forced to accept higher labor costs.”

So it’s not about the inflationary environment? It’s clearly true that companies with market power that don’t rely on collusion have an easier time charging more. It’s not clear why they’d keep that extra bit of market power when demand wanes.

Both Walmart and Target have had ups and downs. One issue is inflation hurting lower-income buyers; Walmart made up for this by attracting more higher-income buyers (who presumably themselves are moving downmarket because of inflation). Target was more vulnerable because they normally attract customers with a wider swathe of incomes. The idea that Walmart in particular is using market power to hike prices feels like an incomplete thought at best.

When supplies are interrupted anybody who have (or receive limited amounts of) product have monopoly power. As long as there are no other competitors who have plenty of that same product in stock, Walmart can set a much higher price if they are lucky enough to get some of that product. That is why car dealer were able to sell vehicles at above sticker price. No competing car dealers had or were willing to sell the same car for less.

Ivan, you’ve misunderstood how that works. If retailers could sell more, they would. There is indeed competition for Walmart (very convenient here to forget that Amazon exists). And you’ve glossed over supply constraints that the retailers themselves face.

Except fraud is not inflation, it is fraud. Using the 2021 shipping crisis to artificially boost prices beyond actual demand is liar inflation. When the grift ends, the inflation bubble pops and productivity surges because it was never that low in the first place.

As long as —– doesn’t screw up the supply chains again (with their zero Covid absurdities) …

[ This is entirely incorrect and malicious.

To dictate the way in which public health is handled, to a country that has done splendidly in protecting public health is intolerably immoral. Countless lives have been saved, public health has been splendidly protected.

As Tesla and Warren Buffett’s investment in BYD show, supply chains have been and are fine all the while public health has been superbly protected.. ]

ltr,

Obviously what you need to do here is to let people know how many people per million have died of Covid in China. This is not a number any of us have seen before, and letting us know about it will completely change the discussion here, I promise.

As today’s NYT introduces elasticity in their discussion of inflation, and there is news about DOJ and firms, this is a reminder about price elasticity of demand.

Products that are narrowly defined e.g., a monopoly board game, have a low-price elasticity of demand. So, if we measure inflation here, we will find it.

Products more widely defined, e.g., all board games, have a larger price elasticity of demand; substitution among games is possible. So, inflation may not be noticeable.

Products that are very widely defined, e.g., games including electronic ones, have a an extremely large price elasticity of demand, maybe infinite.

So, inflation here is nil.

Here is where BLS’s agglomerations are helpful

Hence firms have an incentive to make their product unique. Fords are not Chevies because there is product differentiation. It only has to be perceived by the buyers who are active in the market Here inflation occurs but is moderated or trimmed by the buyers of vehicles.

Hence DOJ has an interest in unfair competition etc.

But we all knew all of this, right?

Ford and Chevy have had different branding for decades – whether the economy was hot or not. Same with any number of companies in any other industries. The idea that the DOJ might go after auto manufacturers over antitrust is a stretch, because the idea that manufacturers have lots of market power is a stretch.

Lovely. You don’t comment then enough.

Not you job, know, but this is really useful and well done.

This is a great share and an interesting analysis.

I’m seeing lots of comments here about how inflation is about market power, but a) that is not even half the story, and b) it misses the point of the paper being summarized here.

The big takeaway of the paper as far as I can tell is that the inflation channel through wages through workers’ short-run inflation expectations can be short-circuited through the Fed’s cutting down on aggregate demand. In other words, this is about monetary policy working the way the Fed hopes it works, more or less.

It’s also interesting that the “there’s clearly not a recession today” crowd is not more hawkish on inflation. We’ve had some of the fastest policy rate hikes ever – and the job market remains hot hot hot while inflation seems to be coming down. Doesn’t that mean hiking rates aggressively was a good idea? Doesn’t that mean hiking rates earlier might have been appropriate (as people like Paul Krugman now seem to concede)? Doesn’t that mean that discretion (vs rules) might give us good reason to be hawkish when short-run indicators aren’t all that hot (say, in 2021, or in 2014)?

“In addition to the unemployment gap, our wage Phillips curve includes household short-run and long-run inflation expectations from the University of Michigan, and lagged core price inflation, which abstracts from volatile food and energy price inflation, to capture the possibility that workers and firms are directly influenced by previous price inflation when agreeing on wages.”

It makes sense, I suppose, that profits are not included in an estimate of a wage Phillips curve, but that means we don’t learn from this article whether profit compression might prove a buffer against inflation – a shift in income shares from capital to labor. Among land, labor, capital and entrepreneurship, we seem mostly to think of land and labor as causing inflation, and so we think mostly of land and labor as potential solutions for inflation.