Today, we’re pleased to present a guest contribution by Rob Fairlie Professor of public policy and economics at UCLA.

Federal, state and local governments spend billions of dollars each year on incubators, training programs, loan programs, tax breaks, and investor incentives to encourage business formation with one of the primary goals being to create jobs. However, these expenditures are often made without knowing whether these programs create lasting, decent-paying jobs.

Over the past seven years, I have been working on a project at the U.S. Census Bureau with Zachary Kroff, Javier Miranda and Nikolas Zolas to provide a new set of statistics on job creation and survival using all business startups. The findings were recently published in a book of entitled, “The Promise and Peril of Entrepreneurship: Job Creation and Survival among US Startups” with MIT Press. https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262545358/the-promise-and-peril-of-entrepreneurship/

Two summary statistics from federal government releases on startup job creation and survival rates are often highlighted – each startup creates 6 new jobs on average, and 50 percent of startups survive up to 5 years. But those numbers focus only on new businesses with employees. Millions of businesses start with no employees every year and a small percentage of them ever reach the hiring stage.

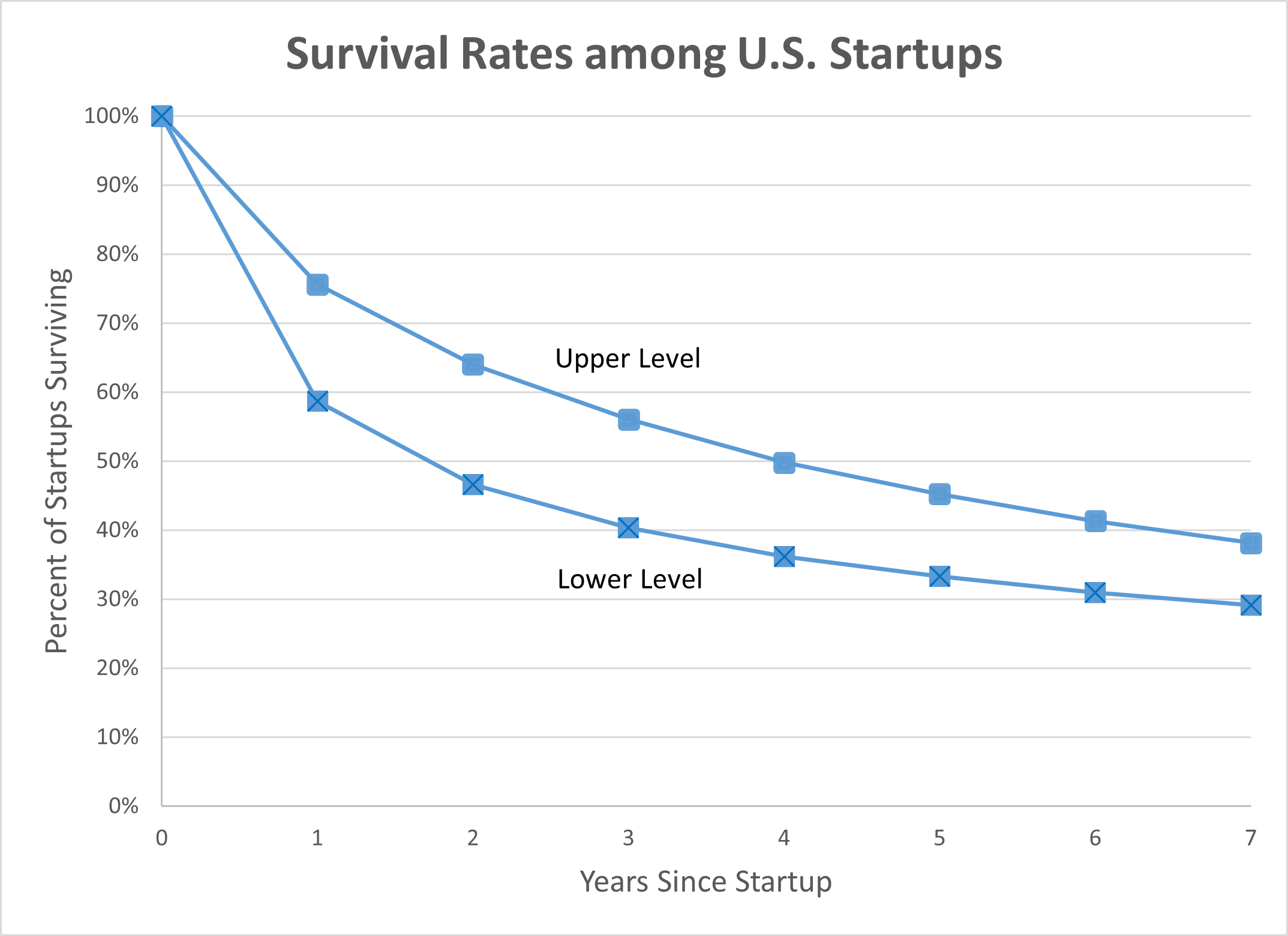

We find that job creation per startup is much lower than federal statistics on new employer businesses that are typically quoted. We find that each startup in the United States creates from 0.7 to 2.6 jobs in the first year after startup – numbers that are much lower than 6 jobs per startup. We also find lower survival rates for startups. A large shakeout occurs in the first few years, leading to only 33-45 percent of startups surviving after five years.

Figure 1.

Startups, however, are still very important for job creation in the U.S. economy. The average annual cohort of 4.1 million startups in the United States creates a total of 3.0 million jobs in the first year after startup and employs 2.6 million workers five years later. Without these jobs created by startups, net job creation would be negative as older businesses lose jobs on average.

We hope that these new findings make it clear that public policies attempting to spur business creation need to consider the wide variety of businesses types and entrepreneurs, and be realistic about how many jobs can be created by new entrepreneurs.

This post written by Rob Fairlie.

As I understand it, the authors has added a category of firm to those counted as new firms by the government. (Is “startup” the term used by government statisticians?) So the data already published are correct, as far as they go, but leave out firms which employ just the owner?

By the way, for those who want to play along, here is a page at FRED offering “business formation” data:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/release?rid=443

Some of these business formation series came in handy when discussing the establishment/household employment survey divergence in comments here.

By the way, after leaving government service, I only ever worked in small businesses. I come from a small business family. One thing that is not obvious from the statistics is the wide variety of ways in which firms come unto existence and go out of existence. Some businesses are the life’s work of their owner and simply close when the owner retires. Some businesses are intended to exist for a limited time; once the purpose is served, they close. Small business owners often have several businesses, sometimes financially entangled, sometimes not. Businesses are sold and then absorbed into another business, or merged, and close as a formal matter, but chug right along in reality. “Fail” is often used to describe the closing of a small business, but that is simply wrong in many cases. Those businesses closed, but may not have failed.

So just eyeballing the graph, it looks like the median survival time is between ~1.8 years (lower level) and 4 years (upper level).

I’m assuming that the survival curves were built using censored and uncensored observations in the usual way, but are the curves parametric (e.g., Weibull curves) or non-parametric (e.g., Kaplan-Meier curves)?

For me the thing that I always go back to is, subsidies and tax breaks don’t help these companies in the truest sense. You’re either going to sink or swim, regardless of subsidies. And if you need subsidies to stay afloat then you had no damned business going into business anyway. Am I including environmental/green business in that?? Yes, because they would stomp on coal and petrol the same day the U.S. and other governments decided they weren’t going to subsidize petrol and coal etc. I think natural gas still has a place in the convo, but the subsidies for oil and coal need to stop. Petrol and coal CEOs give lip-service to “private markets”, then they have their begging hands out worse than the homeless guy at the road intersection. Just because the lobbyist is behind closed doors with some Senator or Governor, doesn’t mean it’s not just another form of begging. It’s time Petrol and coal CEOs put up action on their belief in private markets or STFU.

Amen.

China Watch good news/bad news. Bad news first –

Manufacturing growth slows:

https://www.caixinglobal.com/2023-09-05/growth-in-china-services-sector-slows-as-exports-shrink-caixin-pmi-shows-102100314.html

Country Gardens makes last-minute bond payment:

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/05/business/china-country-garden-debt.html

Speaking of China, here’s an interesting take:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/09/04/china-global-economy/

The important point for the rest ofthe world is that China’s insistence on domestic production over imports means that slack demand in China may have little spill-over through finished good production.

Intermediate goods, raw materials and finance all present other pathways for the transmission of effects from China’s slowdown. Speaking of finance, the article notes that devaluation of the yuan could increase harm to the rest of the world from China’s problems.

In the world of pie-in-the-sky speculation, China’s slowdown might mean China’s economy will never grow larger than that of the U.S.:

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-09-05/china-slowdown-means-it-may-never-overtake-us-economy-be-says

That’s may put a dent in Xi’s ego; should studied economics, maybe.

Whatever one thinks about the long-term arc of China’s development, I think in the short term the Fed needs to start thinking how this effects USA inflation over a 1–5 year time span. Do they want to get caught with interest rates >200 basis points higher than is ideal if China crumbles quickly?? They keep patting themselves on the back because supply chains are now nearer to normal and they are flying blind on how China effects macro demand. It’s incredibly incredibly short-sighted, and, uhm dumb.