Follow up on this post from two and a half years ago:

Figure 1: Year-on-year CPI inflation (blue), and lagged 71 years (852 months) (tan). Source: BLS via FRED, and author’s calculations.

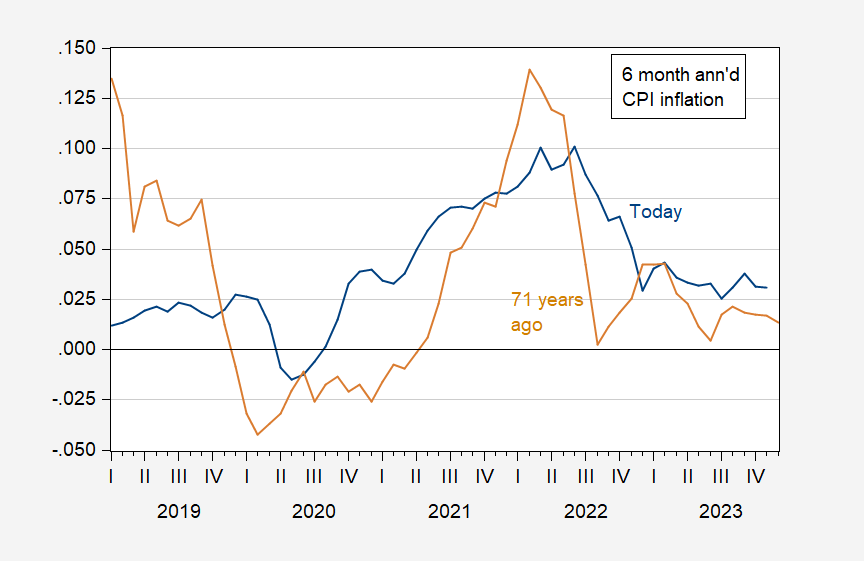

On a half-yearly annualized basis:

Figure 2: 6 month annualized CPI inflation (blue), and lagged 71 years (852 months) (tan). Source: BLS via FRED, and author’s calculations.

The similarity to 71 years ago extends beyond the performance of inflation. FRED doesn’t have data on the effective funds rate for the early 1950, but the Romers tell us that the Fed raised the real overnight rate in response to inflation in the 1950s:

https://www.nber.org/digest/jun02/rehabilitation-monetary-policy-1950s

We should hope the similarities end there. The recession of 1953/4 is conventionally thought of as resulting from Fed tightening.

The Fed didn’t begin playing with the Fed Funds rate until the late 1950’s, but changes in the Discount Rate from the FRB in NY are available all the way back to the 1910’s. Of course, all FRB branches had the same rates after the mid-1930’s:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M13009USM156NNBR

In 1945, the rate was 1%. In response to galloping inflation in 1947-48, it was raised to 1.5%. In 1950 it was raised to 1.75%, and then in 1952 to 2%.

The two immediate post-WW2 expansions both bear a lot of resemblance to the post-pandemic expansion. I think the first one (1946-49) is even more apposite, because it featured 20% inflation impacted by both supply and demand. The shallow 1949 recession occurred *after* that inflation came down, and at least part of that was a temporary freezing up of new home building due to both sharply increased prices, and somewhat higher mortgage rates as well.

In our current situation, all signs are that manufacturing has been in a shallow recession. More than any other sector, the surprising resilience in new apartment and non-residential construction has been a major factor in the economy’s continued expansion.

Good point. At first glance, the discount rate seems at odds with what th Romers claim, that using a Taylor rule shows a rise in real rates. The discount rate does not:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1dPxB

I’ve only read the civilian version so far, but I’m going to have a look at the Taylor rule stuff in the Romers’ paper.

“Policymakers in the 1950s acted similarly to their modern day counterparts, based on the researchers’ Taylor rule estimates.”

Macroeconomic policy matters. Of course Princeton Steve has no clue as he thinks it was all the pandemic. Of course Stevie does not know the difference between the Taylor rule and what Irving Fisher wrote about interest rates.

Does 71 years ago = 1948? We had high inflation for a while in the late 1940’s followed by temporary deflation. Correct me if I got this wrong but didn’t the Korean War inflation surge last only a year and was basically gone by the time Truman left office.

Not even remotely comparable. The comparison would be the post-1918, Spanish flu, period. A shut-down, supply-constrained economy with significant inflation; a sharp, deflationary correction; followed by a near decade-long economic boom.

If we’re talking suppressions, that’s the model to use.

Steven Kopits: See this post.

See this post: https://www.princetonpolicy.com/ppa-blog/2024/1/8/wars-korea-vs-ukraine

I’m struggling to understand why one would use the Korea War precedent.

At the beginning of the Korean War, inflation was running at -0.2%. At the beginning of the Ukrainian war, inflation was running at 8.0%.

In the first months of the Korean War, US defense spending soared from 7.3% to 16.0% of GDP.(!) During the Ukrainian War, US defense spending will have decreased from 3.6% of GDP to 3.2% of GDP.

I struggle to understand the parallels, but maybe you can enlighten me.

Your tendency toward broad, self-assured declaration reliably makes you unreliable. Ego is a poor substitute for thought.

You have chosen ine factor – disease – and declared it to be all that matters to comparability. Says who? You? Laughable.

The transition from an economy in a war footing to a peacetime economy involves both supply and demand adjustment, as did the transition from sheltering at and working from home to being out in the world.

The service sector in the second decade of the 20th century was far smaller as a share of the monetary economy than it is today – “not even remotely comparable”. Travel was far more limited – “not even remotely comparable”. The use of credit by households was miniscule relative to today – “not even remotely comparable”. See? Anybody can play.

One of the least useful habits of mind is to accept one’s own first thought as the final word. That’s where ego comes in. Try thinking things through before you draw conclusions.

Exactly – if you want to compare two periods to each other you should be fully aware of what effectors were similar and what were different. The comparison may still be able to produce insights, but not if you ignore confounders.

Oh, and we aren’t “talk suppression. You’re talking to yourself.

Do you even know how to look up inflation data? Dude – you can make up all the stupid comments you want (aka suppression) but try to at least get the damn inflation data right.

I would blast your latest stupidity but others have already done so including a new post ala our host.

Seriously dude – are you trying to win the 2024 troll of the year award like you won it for 2023? n

“If we’re talking suppressions, that’s the model to use.”

There is no such thing as a suppression model. Now we get all sorts of bloviating ala Princeton Stupid Steve but that does not constitute an economic model.

Nikki Lightweight on Trump: “He was really good at breaking things but not at fixing things”. OK And “Rightly or wrongly chaos follows him everywhere”. Ah Nikki – Trump creates that chaos.

Oh wait Nikki also says “Trump was the right President at the right time”. Now what the eff does that mean unless Nikki wanted racism to grow exponentially. After all to her – slavery was not a problem.