One shouldn’t just say increasing (or decreasing) trade between potential adversaries predicts something.

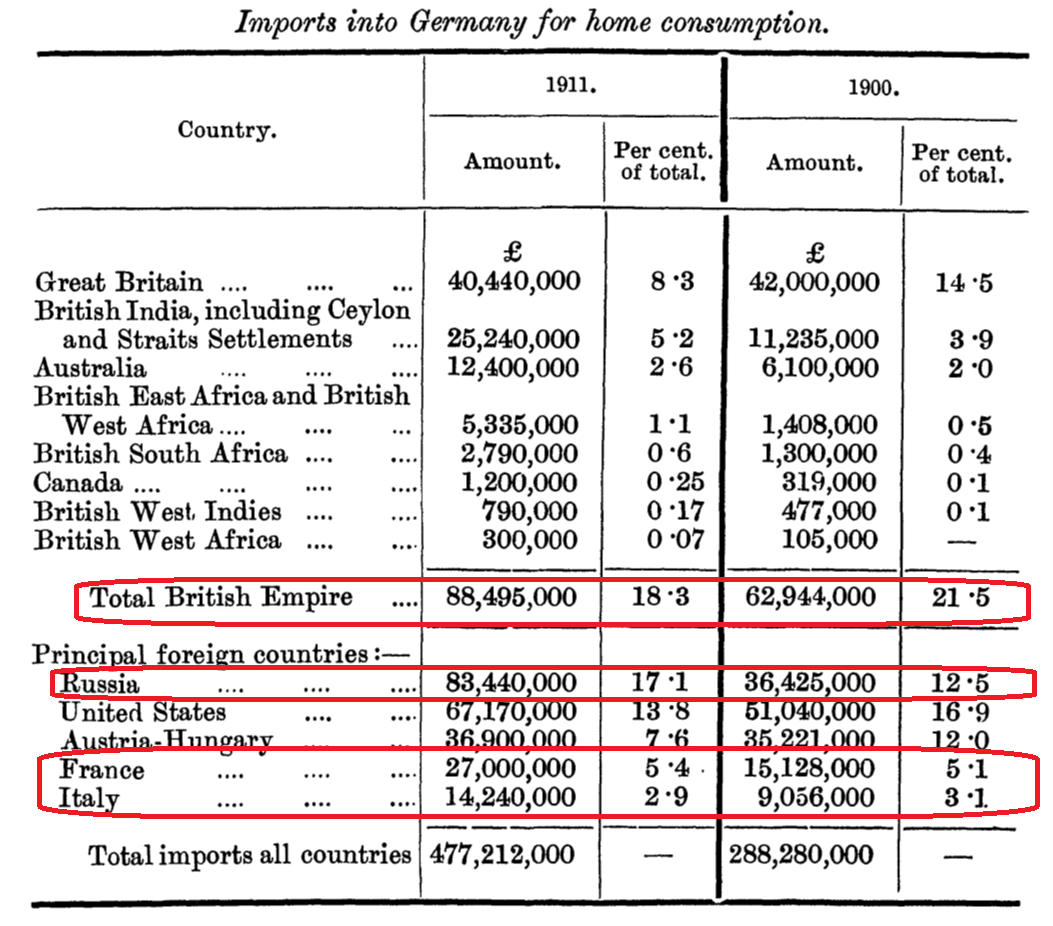

Source: Crammond (1914), p.790.

In 1911, the percentage of German imports coming from UK empire, Russia, France and Italy was 43.7%, compared to 42.1% in 1900.

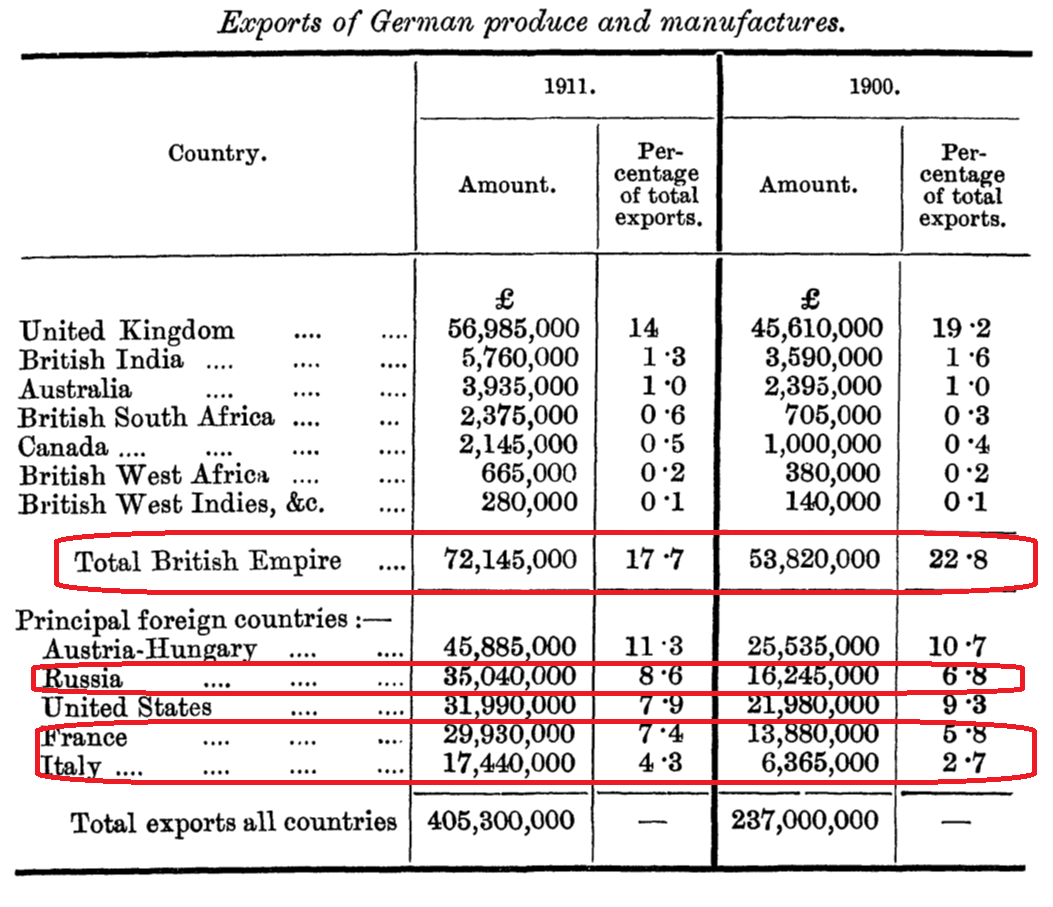

Source: Crammond (1914), p.790.

In 1911, the percentage of German exports going to the UK empire, Russia, France and Italy was 38.0%, compared to 48.1% in 1900. Hence, the concentration of trade is going in a different direction. However, it was not primarily going to allies (e.g., Austria-Hungary), but to the rest-of-the-world. As Crammond (p. 791-2) notes:

Germany has no overseas Empire capable of exchanging a large trade with the motherland, and she has, therefore, been compelled to seek markets in every part of the world. Her eflorts in this direction have proved entirely successful. German trade is yearly becoming more widely spread throughout the world, and she is, to-day, much less dependent upon any one single market than she was in 1900.

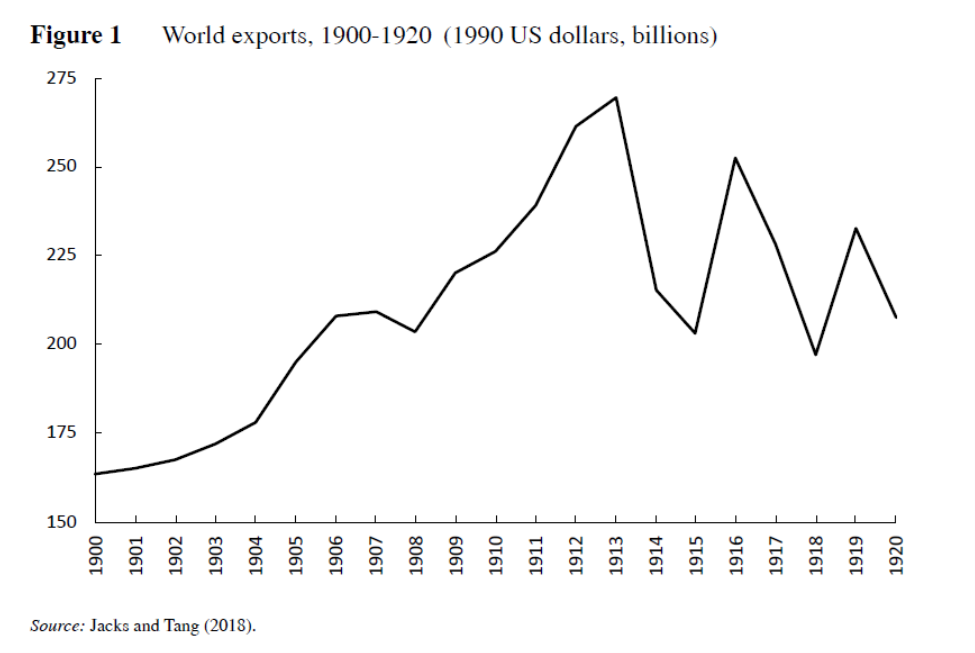

Note that trade values were rising during this time period, so that actual exports to the UK and British Empire were rising.

Source: Jacks (2018).

For some recent work on trade and conflict, see Chen and Evers (2023).

And, as always when thinking about trade and power, read Hirschman (1945).

Another Princeton Steve rant bites the dust.

Hirschman only cost $5.95. Well, now it’s free, so that’s good.

The claim that bilateral trade, or trade in general, prevents war, has a venerable history. In part, that claim was built in logic and hope. In part, it was simply an easy assumption on the part of liberal (Adam Smith-style) thinkers. The logic, it turns out, was always flawed.

If you have grains and I have timber and we trade, we both benefit. No need for war, right? Except that if I take your grain-producing lands, I have the spoils of war and the domestic political benefits of war. Except for global powers, it’s more likely that I will trade with and go to war with my neighbors than with some distant country.

The idea that trade prevents war is simplistic, but makes a great story if you want to promote trade.

“Knowing how states use economic weapons is critical for understanding modern power transitions.6 The empirical record demonstrates that when a dominant state is in decline and perceives a threat from a rising competitor, it will often seek to cut off the latter’s access to supply chains in order to contain its economic growth. Britain disrupted Germany’s access to shipping lanes at the outset of World War I, and raised rubber prices for the United States during the interwar period. The United States, in turn, banned sales of advanced satellite technologies to Japan in the 1980s and of semiconductors to China in the late 2010s. Rising states have adopted countermeasures to fight back and sustain their growth: Germany made its industrial production more efficient, the United States switched to cheaper rubber suppliers in Liberia, and Japan and China upgraded their respective technological bases to circumvent U.S. trade restrictions.” – Chen and Evers

So Trump’s stupid trade war was why we needed to increase defense spending. Way to go Donald.