Today, we present a guest post written by David Papell and Ruxandra Prodan-Boul, Professor of Economics at the University of Houston and Economics Lecturer at Stanford University.

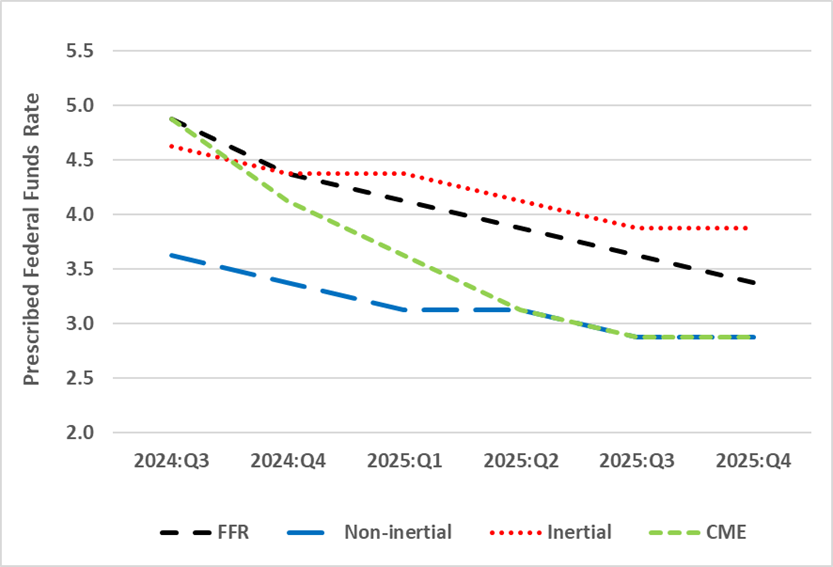

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) lowered the target range for the federal funds rate (FFR) by ½ percentage point from 5.25 – 5.5 percent to 4.75 – 5.0 percent at its September 2024 meeting and, in the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), projected further decreases with a range for the FFR between 4.25 and 4.5 percent by the end of 2024 and between 3.25 and 3.5 percent by the end of 2025. Futures markets summarized by the CME FedWatch Tool after the meeting predicted a faster path of rate cuts with a range for the FFR between 4.00 – 4.25 percent by the end of 2024 and between 2.75 – 3.00 percent by the end of 2025.

We compare the FOMC projections and CME predictions to prescriptions of non-inertial policy rules where the FOMC achieves the desired rate immediately and inertial policy rules where the FOMC smooths rate changes. The post is based on two of our papers. “Policy Rules and Forward Guidance Following the Covid-19 Recession,” published online in the Journal of Financial Stability, and “Alternative Policy Rules and Fed Policies,” which use data from the SEP’s for September 2020 to June 2024 to compare a wide variety of policy rule prescriptions with actual and FOMC projections of the FFR. In this post, we analyze four policy rules that are relevant for the future path of the FFR, update the policy rule prescriptions through December 2027 from the September 2024 SEP, and include futures market predictions.

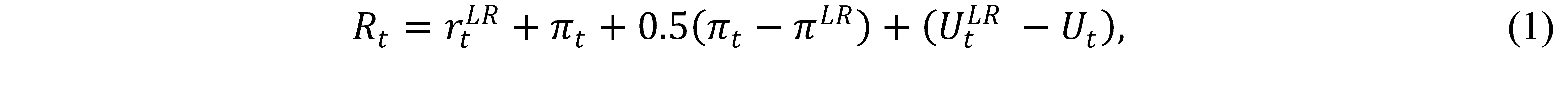

The Taylor (1993) rule with an unemployment gap is as follows,

where is the level of the short-term federal funds interest rate prescribed by the rule, is the inflation rate, is the 2 percent target level of inflation, is the 4 percent rate of unemployment in the longer run, and is the current unemployment rate. is the neutral real interest rate from the SEP which equals 0.5 percent between September 2020 and December 2023, 0.6 percent in March 2024, 0.8 percent in June 2024, and 0.9 percent in September 2024.

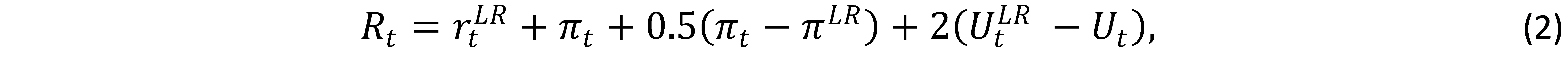

Yellen (2012) analyzed the balanced approach rule where the coefficient on the inflation gap is 0.5 but the coefficient on the unemployment gap is raised to 2.0.

The balanced approach rule received considerable attention following the Great Recession and became the standard policy rule used by the Fed.

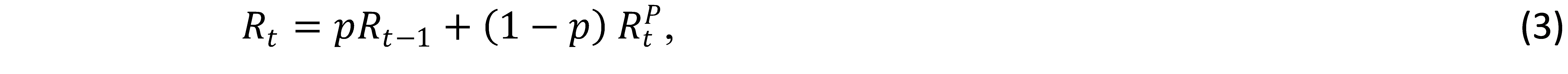

These rules are non-inertial because the FFR fully adjusts whenever the target FFR changes. This is not in accord with FOMC practice to smooth rate increases when inflation rises. We specify inertial versions of the rules based on Clarida, Gali, and Gertler (1999),

where is the degree of inertia and is the target level of the federal funds rate prescribed by Equations (1) and (2). We set as in Bernanke, Kiley, and Roberts (2019). equals the rate prescribed by the rule if it is positive and zero if the prescribed rate is negative.

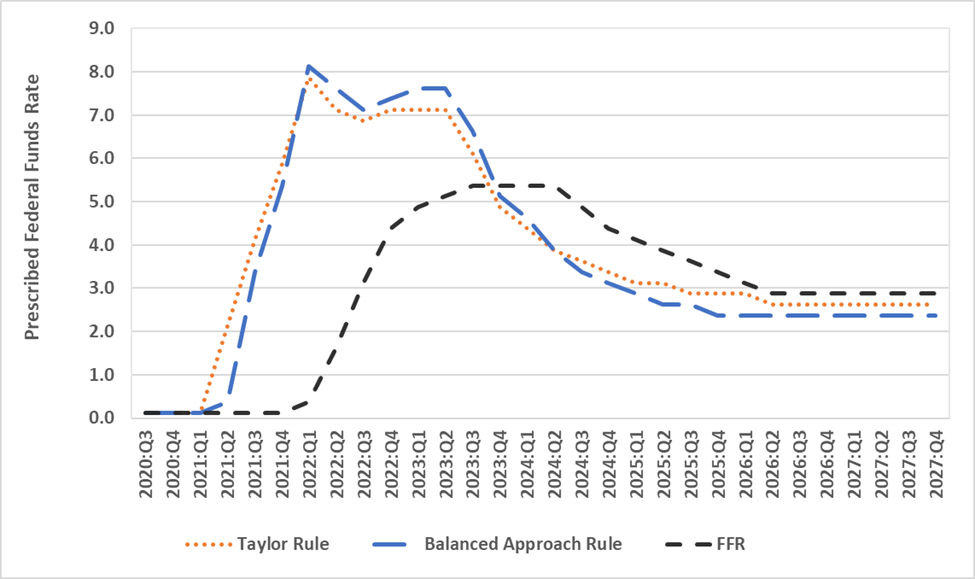

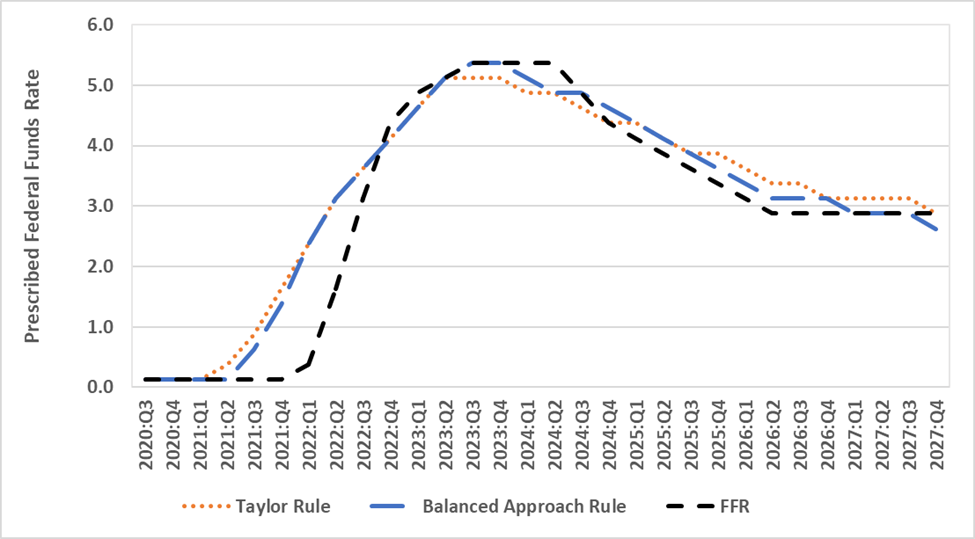

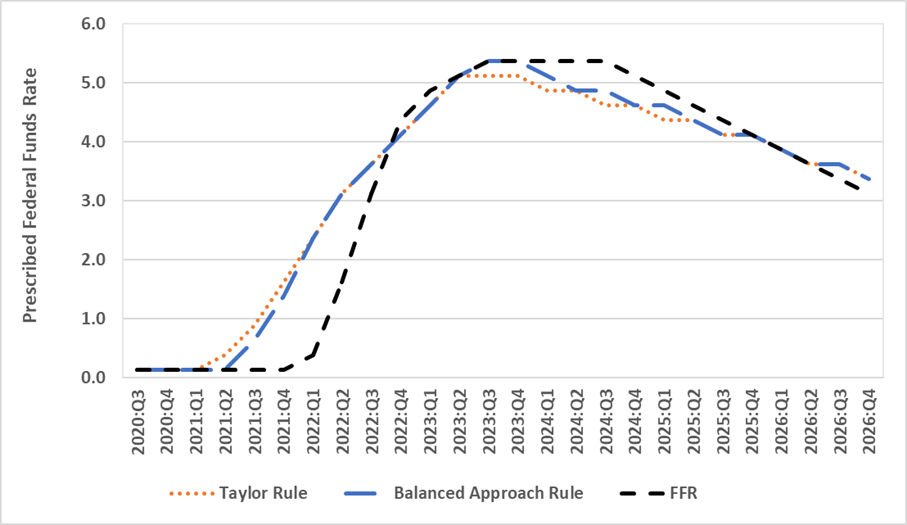

Figure 1 depicts the midpoint for the target range of the FFR for September 2020 to September 2024 and the projected FFR for December 2024 to December 2027 from the September 2024 SEP. Figure 1 also depicts policy rule prescriptions. Between September 2020 and September 2024, we use real-time inflation and unemployment data that was available at the time of the FOMC meetings. Between December 2024 and December 2027, we use inflation and unemployment projections from the September 2024 SEP. The differences in the prescribed FFR’s between the inertial and non-inertial rules are much larger than those between the Taylor and balanced approach rules.

Policy rule prescriptions are reported in Panel A for the non-inertial Taylor and balanced approach rules. They are much higher than the FFR in 2022 and 2023 and are not in accord with the FOMC’s practice of smoothing rate increases when inflation rises. In contrast, while the policy rule prescriptions for 2024 through 2027 from the September 2024 SEP are consistently lower than the FFR projections, the gap narrows considerably in 2026 and 2027. The inertial rules in Panel B prescribe a much smoother path of rate increases in 2021 and 2022 than that adopted by the FOMC. Between December 2022 and September 2024, the policy rule prescriptions are close to the FOMC projections and, looking forward, the prescriptions continue to be close to the projections.

Figure 1. The Federal Funds Rate and Policy Rule Prescriptions for September 2024

Panel A. Non-Inertial Rules

Panel B. Inertial Rules

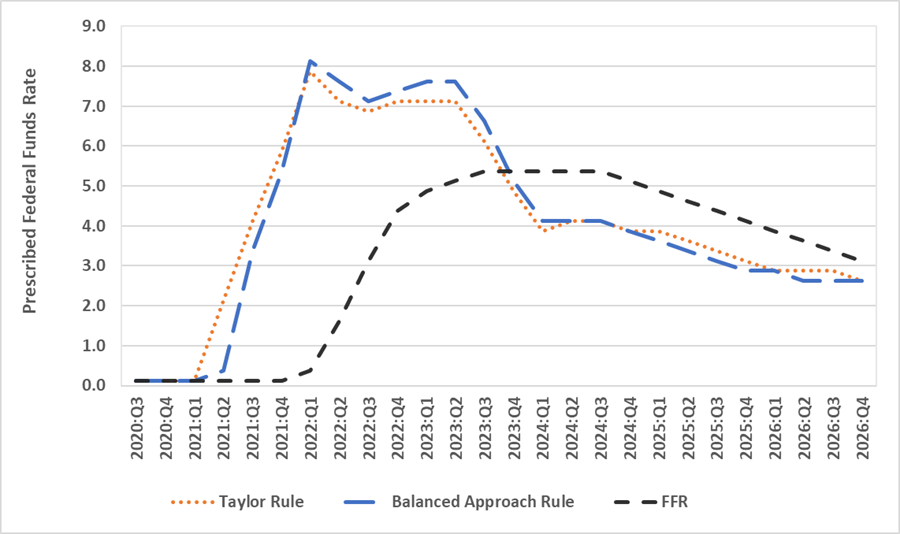

Figure 2 illustrates the federal funds rate projections and policy rule prescriptions from the June 2024 SEP to see how much has changed in the past three months. Panel A depicts prescriptions from the non-inertial rules. For the Taylor rule, the gap between the projections and the predictions is about the same in 2024 and 2025 with the June and September SEP’s because the rate decreases are approximately equal. For the balanced approach rule, the gap is smaller because forecasted unemployment increased between the June and September SEP’s and the FFR responds more to increases in the unemployment gap with the balance approach rule than with the Taylor rule. The gap between the projections and the predictions narrows in 2026 for both rules. Panel B depicts prescriptions from the inertial rules. While the size of the gaps is narrow and similar between the June and September SEP’s, the FFR projections are generally above both policy rule prescriptions in June and below both prescriptions in September.

Figure 2. The Federal Funds Rate and Policy Rule Prescriptions for June 2024

Panel A. Non-Inertial Rules

Panel B. Inertial Rules

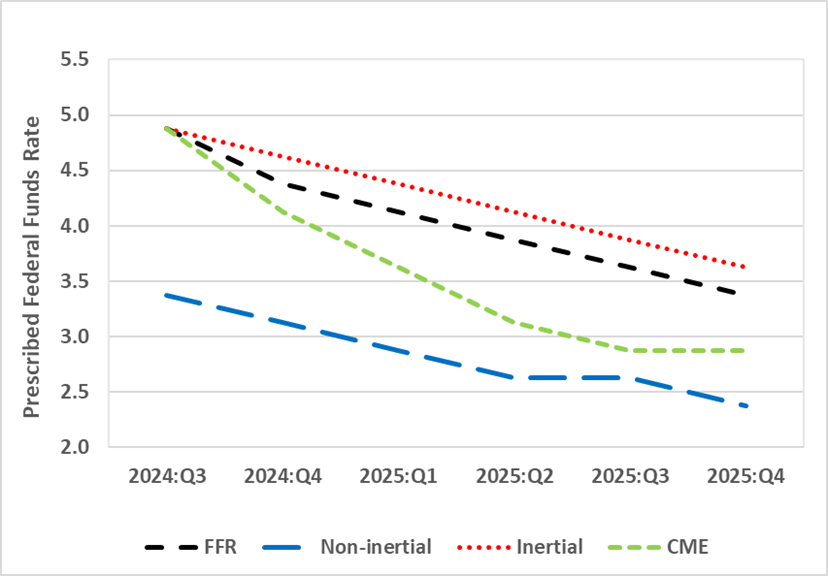

Figure 3 shows the median predictions from futures markets in the CME FedWatch Tool the day following the September 2024 FOMC meeting through the end of the CME prediction horizon in September 2025. The futures markets predict sharper decreases in the FFR than the FOMC projections. We add to this discussion by including prescriptions from policy rules. Figure 3 shows that, for both Taylor and balanced approach rules, the prescriptions from the inertial policy rules for December 2024 through December 2025 are above the futures market forecasts. For the non-inertial Taylor rule, the prescriptions are below the futures market predictions through June 2025 and equal thereafter. For the non-inertial balanced approach rule, the prescriptions are always below the futures market predictions. Comparison between futures market predictions and policy rule prescriptions depends more on the choice between inertial and non-inertial rules than on the choice between Taylor and balanced approach rules.

Figure 3: The Federal Funds Rate, CME FedWatch Tool and Policy Rule Prescriptions

Panel A. Taylor Rules

Panel B. Balanced Approach Rules

This post written by David Papell and Ruxandra Prodan-Boul.

recent commentary by trump clearly demonstrates the guy is simply too old and out of touch to be elected to office. he makes Biden look like Einstein for crying out loud. trump thinks hurricanes don’t form in September?! seriously. is there a filter at all on him, or is his mouth simply a full bore sewage break?

I was wondering about your claim but yep – here is the story:

https://www.yahoo.com/news/donald-trump-dumb-af-hurricane-065554599.html

“It’s so extensive, nobody thought this would be happening, especially now it’s so late in the season for the hurricanes.”

However, it is currently slap-bang in the middle of hurricane season.

Per the Florida Climate Center’s website:

The threat of hurricanes is very real for Florida during the six-month long Atlantic hurricane season, which runs from June 1 until November 30. The peak of hurricane season occurs between mid-August and late October, when the waters in the equatorial Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico have warmed enough to help support the development of tropical waves.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which climate experts fear Trump will dismantle if he returns to the White House, states the same date range: “The Atlantic hurricane season is June 1st to November 30th.”

Thank you. Nicely done. This is the analysis I was looking for.

Some questions. The analysis would seem to imply that the FFR comes back to some steady state value around 2.5 – 3.0% by H2 2026. Why this number? If we look at the FFR post-GFC, the steady state value appears to be more in the 1.5 – 2.25% range. Thus, the implied steady state forecast would appear to be 0.75% higher than the comps (best one can tell) in the period from 2002. Have the fundamentals changed since then? In what respect?

The analysis would also seem to imply a soft landing. What are the historical odds of this, allowing for suppression v recession? Overshoots are common during corrections. What would be the conditions for an overshoot to the downside? How likely would that be on a historical basis?

What is the path of the unwind of housing values? Or do we believe they are permanently high? Surplus housing under construction appears to be about twice as great as it was during the housing bubble in 2005-2007. Further, Home Price to Median Household Income Ratio is at historical highs, even greater than during the prior bubble. How does this unwind? What are the implications for the FFR?

https://www.longtermtrends.net/home-price-median-annual-income-ratio/

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNDCONTSA

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FEDFUNDS

“What are the historical odds of this, allowing for suppression v recession?”

Some problems with your question:

1) “…allowing for suppression vs recession” makes the question ambiguous. You haven’t asked a clear question, so you can’t expect much of an answer.

2) “Suppression” is a term you made up, which doesn’t have any meaning in economics.

3) There is no way to attach probabilities to a circumstance that doesn’t exist.

If we leave out the nonsense part of your question, then you’re asking the odds of recession. That question is routinely addressed in blog posts here.

1. & 2.

If you look, you’ll see that the FFR was at zero percent for seven years, from Jan. 2009 through 2016. The only other time we see this phenomena is during the Great Depression. So the question is whether the Great Recession was a depression or not. I think it was a depression, and if it was, how should we call it? I believe the reason for the recession was linked to the incorporation of China into the global economy, hence, ‘China Depression’.

On the other hand, if you believe that the recession ended in 2009, then how do you want to treat the FFR, and by implication mortgage rates, during the 2010-2016 period? Were those normal mortgage rates, or rates held low by the depression? If you want to say that the FFR from 2010-2016 was ‘normal’, then the steady state FFR during the prior decade, that is, from 2010 through 2019, would have been about 0.6%. In this case, then why would P&P-B’s implied steady state forecast FFR be in the 2.5-3.0% range, not the 0.5-1.0% range? So how do you want to handle the 2010-2016 period for the FFR? Was that normal? If not, how would you want to distinguish that period from normalcy? If you use the notion of a ‘China Depression’, then 2009-2016 can be characterized as an anomalous period with lower than normal interest rates and thus excluded from an estimate of the average applicable to a steady state forecast. So the China Depression concept matters for how you think about P&P-B’s implied steady state forecast for the FFR from H2 2026.

As for suppression v recession: If you think that the covid downturn was just another downturn, then you can use historical precedents from previous recessions without much concern. On the other hand, if you think covid was a suppression, not a recession, then you have to be quite careful in applying historical precedents to any analysis or projection of an overshoot of interest rates to the downside. I am pointing that out.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FEDFUNDS

“…If you think that the covid downturn was just another downturn, then you can use historical precedents from previous recessions without much concern. On the other hand, if you think covid was a suppression…”

You’re indulging in word games here. You’ve suggested that the word “recession” applies only to economic contractions that are caused in some unstated “normal” way, but not to contractions caused by pandemic. You’ve just made that up – you don’t make the rules. Earlier, you made a distinction between “depression” and “recession”, when there is no official or academic distinction. The idea of another depression was so stressful that we picked a new word for the same thing. It was a rhetorical choice, not an analytic one.

Actual analysis should ALWAYS take care in applying historical precedent. If you don’t, that’s your problem.

If, instead of treating “recession” and “depression” and your made-up “suppression” as distinct states of the world, you were to do what real economists do – rely on data, theory and judgement rather than labels – you wouldn’t end up trying to make crude labels into precise distinctions. Nor would you try to shoe-horn made-up distinctions into discussions of real circumstances.

Stop babbling about labels and do some real thinking.

“the steady state FFR”

Stevie learns a new term. “Steady state”. Now Stevie is too dumb to know his new pet term has NOTHING to do with this discussion. Yea – the man is dumb. But he keeps on going and going and going.

He means voter suppression?? That’s a Republican caused problem.

I have on several occasions listed the difference between suppressions, recessions and depressions, for example, here:

https://www.princetonpolicy.com/ppa-blog/2022/2/27/recessions-depressions-and-recessions

Steven Kopits: Yes, but nobody else shares your definitions, so use of the term hardly aids in comprehension in your audience.

Well, if the audience did some reading, maybe that would help them. Maybe it would help you. You can clearly see the problems of conflating the covid suppression with an ordinary recession. Was pushing the FFR to zero during the pandemic a massive mistake? I think so. Was it a massive mistake during the GFC and the aftermath (let’s call that the China Depression)? No. It didn’t help that much, but it certainly wasn’t a mistake. So then those two events must have been something different. If you don’t distinguish them, then you’re analysis becomes muddled, which has been the case in one of your earlier posts.

As the the China Depression, well, is the FFR at zero for seven years normal? Was the 2010-2017 period an run-of-the-mill expansion? Or was it the tail end of something bad? If so, what? Well, the FOMC ordinarily does not put the FFR to zero for seven years in an ordinary recession. But the equivalent of the FFR was at zero for seven years… during the Great Depression.

So we can call a spoon a toothless fork if you like. But if you don’t have the concept of a spoon, however you call it, you’re going to be disadvantaged at the table.

“I have on several occasions listed the difference between suppressions, recessions and depressions”.

What dishonest troll Steven Koptis fails to tell you is that we have taken down the nonsense in this stupid post many times. And he still thinks it is worth reading? Yea – Stevie is THAT DUMB.

Steven Kopits

October 1, 2024 at 2:37 pm

Well, if the audience did some reading, maybe that would help them. Maybe it would help you.

Seriously? You are an arrogant clown. I have read your trash – it is just that. Trash. We have told you why it is trash. But of course Stevie boy is too dumb, lazy, and/or arrogant to read anything beyond his own overinflated bloviating.

So stop it. Get off this blog as you are a total waste of time. Now you have your own blog – which NO ONE reads. Bloviate your arrogant and moronic heart at there.

Could you please stop? More gibberish generated by a complete KNOW NOTHING. You are wasting everyone’s time proving just one thing – You Are a Complete Idiot. We know that – geesh!

It may be the analysis you were allegedly looking for but it seems once again you have no clue what this is about. “Steady state”. Excuse me old incompetent one but where does the Taylor Rule specify a “steady state” interest rate? May the Wicksell natural rate but that is not the same thing economists refer to when they use the term “steady state”

Of course you never had a clue what any of this means so don’t let me get in the way of your pretending you have any insights. You don’t but as usual you will babble on.

And yet, if you look at Fig. 1, it looks like P&P-B see the FFR stabilizing, with really no dynamism in the 6 quarters ending Q4 2027. The implication would be that things have returned to ‘normal’, which is an FFR in the 2.5-3.0% range. It looks like what we used to call ‘steady state’ to me.

I personally think that the FFR is likely to continue to decline on trend to about 1.75% in Q4 2027, which implies some underlying pessimism about the economy, I suppose.

In any event, if the FFR is to be 2.5-3.0% and mortgages in the 5.0-5.5% range, then what is the expected outcome for housing values? Is there a hard landing out there along the lines of 2008-2009, and a continuing depression for seven years? Or something else? And further, how does one handle that with a structural deficit in the 6% of GDP range?

Btw, the sentiment coming out of China today is really quite depressionary. Calls for stimulus programs similar to the US circa 2008 to 2011. If a depression is a balance sheet event linked to housing values (as opposed to a recession being an income statement event), then China is going to go into a depression. I think it has already started.

How effing stupid are you? Your reply has nothing to do with what I said or anything else relevant to the post at hand. Yes we had low short-term rates for a while. That does not mean there is some “steady state” FFR. Look dude – when you finally figure out that you have no effing clue what any of this means, then maybe you will take the time to learn some real economics. Then and only then are you allowed to join the adults here. In the meantime please do the right thing – SHUT THE EFF UP!

The implication would be that things have returned to ‘normal’ (in reference to short-term nominal interest rates???).

I wonder if John B. Taylor is reading this. I would not want him to hurt himself laughing so hard at the utter stupidity of Steven Koptis. And yes – Wicksell is rolling over in his grave

‘Steady state’ is a lower bar than the notion of a ‘natural’ rate (a term which I dislike) or the neutral rate (with which I am fine).

This is the question at hand: Do P&P-B intend their steady state as the neutral rate? And if so, what’s the logic behind that?

Steven, when you use terms like normal and ordinary, you are implying that current conditions are incorrect and that some well defined correct term exists that we simply need to find. I do not think that is accurate. history is a guideline. but why does tomorrow need to perform in a very similar manner to yesterday? just because we have a stable period of time in the past, does not mean the future should repeat that period. perhaps it was the past that was the outlier, and you have labeled it as “normal”. I think you are giving to much weight to the past when trying to predict the future.

Baffs –

If we are going to be in the forecasting business, then we need some basis for those forecasts. P&P-B indicate that the FFR reaches some steady state — call it the neutral rate if you like — from H2 2026. That’s a forecast, at least of a sort. There are other options: We could call it a ‘scenario’ or a ‘conditional forecast’, either a very soft forecast or one loaded with caveats (eg, CBO); an ‘expectation’, a kind of negative forecast; or a ‘forecast’ or ‘projection’, both of which are forecasts.

So how do we make forecasts? These can be technical or fundamental. Technical is based purely on past events, that is, historical data and associated statistical analysis. This is mostly what Menzie does. Or you can do fundamental analysis, in which you consider the specifics of the forecast in terms of anticipated conditions and timing, among others. Mostly I am a fundamentals forecaster, but good forecasters will tend to use both technicals and fundamentals.

Both Vasja and I are asking the same question: How is the steady state rate (is it a neutral rate?) forecast implied in Fig. 1 derived? One way to make such a forecast is technical analysis, that is, assuming the future will look like the past, generally the recent past. If we take the 2010 decade, then the expected FFR would be 0.6%. That assumes that the FFR at zero from 2010 through 2016 was ‘normal’ and that period was an ordinary expansion in an economic sense. A forecast FFR of nearly 3% would then look anomalous compared to the prior decade and therefore require explicit justification.

On the other hand, if the 2010-2016 period was anomalous, then we can drop that stretch for purposes of forecasting. The 3% FFR forecast still looks high compared to most of the ‘neutral’ periods since 2000, but it’s not so far off.

There are other problems, more for policy than forecasting purposes. From 2010-2016, the FFR was at zero and generated basically no inflation nor securities or asset bubbles. This same policy during the pandemic blew out inflation and created asset bubbles which we are still trying to resolve, and did so in a matter of months. So what was the difference? If the Great Recession was just an ordinary recession, then an FFR at zero for the following seven years should have created both inflation and asset bubbles. It didn’t. So was the Great Recession a recession, or something different? And if so, how should we class it? Can we call it a depression? If so, how does a depression differ from a recession? And why a depression? Was it linked to the rise of China, or to something else? Is it fair to call the 2008-2016 period the ‘China Depression’, or did that not happen? Is it just a chimera, as Menzie would seem to imply?

Similarly, the downturn during the pandemic only lasted two months, which would ordinarily not qualify even as a recession. So was the pandemic just another recession, or was it something different? It certainly wasn’t a depression. Housing prices do not soar during a depression. So was it a normal recession? Would the Fed ordinarily put the FFR to zero in an ordinary recession? They have never done that in the past. If the pandemic downturn was not an ordinary recession, then what was it? How should we call it? ‘Recession’ and ‘depression’ are taken. ‘Oppression’ has political overtones. ‘Suppression’ seems about right, because the government was actively suppressing supply with lockdowns (even while stimulating demand!).

You can take the view that the GFC was an ordinary recession which ended in 2009, and that the pandemic was an ordinary recession which ended in 2020. But then you’re left with a quandary. Why was the FFR at zero from 2009-2016 ineffective, on the one hand, but created massive inflation and asset bubbles in a matter a months during the pandemic, on the other? If you don’t have an answer to that, then the forecast of a steady state (neutral) FFR of 3% from H2 2026 is problematic.

Our understanding of the past informs our expectations for the future. How with think of our past matters quite a lot.

Steven, first I would argue that inflation was temporary, fixed, and not nearly as bad as you are describing since the pandemic. it was an issue that was dealt with. you are creating much to great drama about an event that ended up not being that big of a deal.

now, I will point out that the fed and the economy do not exist in a bubble. fiscal policy is just as important as the fed. in response to the financial crisis, republicans intended to damage Obama by limiting our fiscal response as much as possible. hence, we had a prolonged recovery. on the other hand, we learned a lesson, primed and pumped the economy during the pandemic. yes, we go some inflation, but we also certainly constrained the long term economic damage the pandemic could have induced.

Steven, you seem to be claiming a mystery that does not really exist, at least at the level you want to claim. I do not see you providing any valuable insight to the situation, beyond what we already understand.

‘Steady state’ is a lower bar’

Lower bar? Christ you are a MORON. You are using a term which has zero place in this discussion. Then again you have always been clueless what basic economics is.

BTW no one gives a damn whether you like or dislike the terms real economists use. Why – because you are one stupid nobody.

Let me add this:

From mid-2017 to year-end 2019 (that is, after the end of the China Depression to the beginning of covid), mortgage rates averaged 4.2%. The average difference between the FFR and 30 year mortgages was about 2.4%. Thus, an FFR forecast in 2.5-3.0% range would suggest 30 year mortgages in the 5.0-5.5% range. This is not a tragedy, but still almost a full percentage point higher than pre-covid.

This again begs the question of how housing values can be sustained, and what the equilibrium FFR might be to rebalance the housing market.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MORTGAGE30US#0

Roughly stated, mortgage rates are determined by the nominal rate on a “risk-free” hedging security – a Treasury note of some kind – plus a risk premium. The Fed funds rate is never the hedging security; duration on fed funds is nearly zero, while duration in mortgages is measured in terms of years. That makes funds rate forecasts a poor basis for mortgage rate forecasts.

It’s not that poor. If you want the very long term average, it’s 3%. So if I add 3% to the FFR, I will have the 30 year mortgage on average. This would make the implied mortgage rate for FFR of 2.5-3.0% equal to a mortgage rate of 5.5-6.0%. So even higher than I have suggested. This begs the whole rebalancing of the real estate market even more.

If you take a very long-term average as the basis for analysis, you’ll mostly be wrong about the short and medium term – about economic cycles. Your question was about economic cycles. So the funds rate is a poor choice, given your question.

Treasury notes of some duration are mechanically related to mortgages rates in a way that the funds rate is not. Term premium is a reality, and it varies. So the funds rate is a poor choice, given the way the mortgage market actually works.

Don’t want to take my word for it? Maybe LOOK AT THE DATA. Crazy idea, I know, but it’s what I do:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1uDSd

The mortgage rate/funds rate spread is much more variable than the mortgage rate/Treasury spread. That greater variability is the measure of what a bad idea it is to do what you suggest. The mortgage/funds spread is almost always far different from its own average; the average doesn’t describe the series very well. So the funds rate is a poor choice. Period.

That’s fine. Except the post is about the FFR. Do you want to argue that the 30 year will be completely unrelated to the FFR? You think the FFR could be 3% and mortgages 3.5%? Let me help you with that: Ain’t gonna happen. That difference will ordinarily be about 2.5%. The historical minimum is 1.6%.

So let’s take the min: If the FFR is forecast at 2.5-3.0%, then mortgages in the very best case would be 4.1%-4.6%. That’s using the historically smallest differential in the entire record. Now, mortgages rates averaged 4.2% from 2017 to 2019. So even if I use the very best case scenario, mortgages rates from 2027 will be essentially unchanged from pre-covid. On that basis, homes are overvalued by around 26%. How do you see that unwinding?

steven, over the past decade the us has continued to underperform on new housing construction. house prices are a supply and demand issue. we have undersupplied for quite a long time. that is quite different from what happened before the financial crisis-which was caused by financial engineering and plenty of housing supply. there may be some local market corrections, but a lack of new housing will continue to keep prices from falling much i believe. although they may level out for a while. but lower interest rates will push those prices higher.

Baffs –

You bring up a very interesting question, that “over the past decade the us has continued to underperform on new housing construction”.

Has it? I think there’s a kind of assumption that now three years of sky-high housing prices have not stimulated material new construction of private homes. But that’s not true.

During the peak of the last housing bubble, 2004-2007 inclusive, the US built 1.27 million new private housing units per year. In the most recent bubble, 2021-2024, the US built 1.57 million housing units per year. By this measure, the current housing bubble is quite a bit more frothy than the previous. Now, you may counter that there was a shortage of new construction after the Great Recession. And there was. But by my calculations, however, by 2019, housing market conditions had returned to normal.

Thus, the surge of new construction since 2021 has created a new surplus. The surplus peaked in the prior bubble in 2008 at 1.3 million units. The expected surplus for 2024 is 3.0 million units, at least if my math is directionally correct.

The crash came two years after the construction peak. Peak construction was in 2006 in the last bubble. Peak construction looks to be 2023 in this cycle. This would suggest some sort of housing crash during 2025 or 2026. This crash promises to be more severe than the crash in 2009-2012.

Now, my question again: How does the likely correction in the housing market translate into an FFR of 3% in H2 2026 and beyond?

https://www.princetonpolicy.com/ppa-blog/2024/10/3/private-homes-under-construction

Steven, new housing starts:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/HOUST

historically, there is nothing in the data to suggest we are currently in a surplus of new housing. you analysis is incorrect, as you seem to be arguing against the data.

again, there may be some local areas that have recent surplus. but on a national level, there really is no way to argue we have a surplus of housing at this point in time. you are either mistaken or speaking falsehoods.

Taking an average of historical interest rates as a guide to predicting what rates will be in the future? That has to be the dumbest thing since assuming there is some fixed GDP/M2 ratio. You really need to stop as your stupidity is already clear.

The China Depression? Is that akin to your stupid “suppression”? Or your idiotic understanding of the Real Business Cycle model?

Stevie boy – get a new version of ChatGPT as your current version is mentally retarded.

“what the equilibrium FFR might be to rebalance the housing market.”

Could someone pull the plug on the Village Idiot who calls himself Steven Koptis? This babble is killing brain cells globally.

Thank you for a very informative post!

Could I ask the authors if the 3% Federal Funds Rate (FFR) to which the projections from the displayed rules and those of the FOMC converge after 2025 is considered the new long-run value of the FFR?

In Figures 1 and 2, I observe that under all the projection rules and FOMC projections, the FFR is projected to settle at approximately 3% in the medium run (after 2025). This is significantly above the approximate 0% range experienced between 2009 and 2022. Furthermore, given the flatness of both the authors’ and FOMC projections between 2026 and 2027, it seems that this approximately 3% rate will persist beyond 2027 and may be regarded as the new long-run normal.

Assuming a return of inflation to around 2% and an unemployment rate equal to its long-run average, similar to those values experienced between 2009 and 2022, this would imply a sharp revision in the neutral real interest rate (r^lr) sometime after 2022-2024. The typically cited determinants of the neutral real interest rate include productivity growth, demographic changes, and related long-run savings rates. Since these three factors have not experienced abrupt changes since 2022, one might expect the neutral rate to remain at its 2009-2022 value, which contradicts the assertion made at the beginning of this paragraph.

However, all FFR predictions, including those from the very knowledgeable experts at the FOMC, implicitly indicate an increase in the neutral interest rate. I would appreciate any insights the authors could provide to help me understand this better. The most reasonable explanation, in my view, is that the FFR policy regime during the period of 2009-2022—characterized by “lower for longer”—was simply unusual and that we are returning to a “pre-2008” regime in the post-2024 period.

However, I must question whether a return to the “pre-2008” regime is sustainable. Is a sustained 3% FFR feasible if the neutral interest rate remains unchanged, productivity growth continues to be low, other long-run determinants follow pre-2022 trends, and inflation returns to 2% or lower? I assume that the Federal Reserve (Fed) may pursue a 3% FFR for some time, perhaps ignoring the potentially unchanged neutral real interest rate, but not indefinitely.

I must admit that I am likely missing a lot of nuances and would appreciate your help.

+1. Note the discussion of the China Depression above. FFR of zero is not normal and is linked to depressions. So I would drop the Jan. 2009 to Dec. 2016 period for purposes of baseline estimates. Even so, you end up with a predicted FFR in the 1.2-2.4% range.

The China Depression again? Damn – you are one persistent MORON!

“between suppressions, recessions and depressions”

Kopits is going through another one of his Reverend Jesse Jackson phases.

The daily schedule for Kopits’ symposium on words he redefines to something meaningless:

Thursday–oppression

Friday–aggression

Saturday–possession

Sunday–confession

Monday–succession

Tuesday–digression

By next Wednesday you’ll have no idea what the hell any of these words mean.

Vasja, I won’t pretend to answer for the authors, but the FOMC most recently projected that the funds rate over the longer term will be 2.9%.

Check the table here under Federal Funds Rate – Longer run:

https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcprojtabl20240918.htm

So 3% is more or less what Fed policy makers currently think the neutral rate is likely to be. If you go back over the past year of these documents, you’ll find that the projected neutral rate has been edging higher. In December and before, the projected Longer run funds rate was 2.5%:

https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcprojtabl20231213.htm

Something has convinced policy makers that the neutral rate is higher than previously thought. I have not seen an adequate explanation from the Fed for the change. On one occasion, Chair Powell declined to offer an explanation when asked.

I got it wrong. The figure below overlays the quarterly Federal Funds Rate (FFR) (Source: FRED’s M FEDFUNDS, simple average, 02/10/2024) with the Laubach-Williams (LW) Neutral Rate of Interest (rStar, Source: newyorkfed.org, Q LW smoothed estimate, same date): https://ibb.co/n1BR9mf.

As of Q2 2024, rStar is 1.2% but appears to be on a mildly upward trajectory.

That said, the NY Fed’s rStar is based on in-sample data, while the authors include forecasted values. If these forecasts align with actual outcomes, the NY Fed’s rStar could be revised upward, potentially closer to the authors’ estimates (though the filtered estimate, which would be revised less, is also low). The authors’ projection of 3% after 2025 aligns with positive forecasts for inflation and unemployment.

I still find it difficult to reconcile rStar estimates with its supposed fundamental drivers (such as productivity, demographics, the savings-investment relationship…). Nonetheless, in the authors’, NY Fed’s, and most models, rStar is not explicitly estimated using these drivers and this is not the topic that the author’s intend to address in this contribution.

I;m looking over their August 2024 paper which is an interesting read. Something tells me pretend economist Steven Koptis has not read it. You see – the world’s worst consultant wanted to talk about the “steady state” interest rate which is a totally meaningless concept in this context. Now the authors do mention “the neutral real interest rate”, which anyone who gets basic macroeconomics would get. But not little Stevie. To help this moron out, let me cite one key sentence from their paper:

‘The Taylor rule has a coefficient on the inflation gap of 0.5 and a coefficient on the unemployment gap of 1.0. While the rule in Taylor (1993) is written in terms of the output gap with a coefficient of 0.5 and a fixed neutral real interest rate, we follow the MPR and use the

unemployment gap and a time-varying neutral real interest rate.’

OK – Stevie has no clue what the Taylor Rule even is (as well as what it is not as Stevie is dumb enough to claim real rates in Russia follow from some Taylor whatever that means). But catch that, the neutral rate interest rate might be “time-varying” which is a far cry from a “steady state”. Now the adults here who get basic economics will likely know what the Wicksellian neutral real rate might vary over time. But dear little Stevie is so lost here as this clown never learned even the basics of macroeconomics.