In Tuesday’s NYT, Oren Cass makes the case for protectionism.

It would be wonderful to see economists willing to try a new course when the one they’ve pursued has failed so spectacularly for so long. Instead, they are doubling down on their mistakes.

Their most basic mistake is the continued reliance on the theory of comparative advantage. The theory, a mainstay of Econ 101 courses, says that countries should specialize in what they are relatively more efficient at and then benefit from trading the resulting output. An advanced economy like the United States might lose its textile manufacturing, say, but become the worldwide hub for the production of cutting-edge computer chips.

The theory works great in the classroom, but in reality it wasn’t just T-shirts that ended up going overseas. The most sophisticated industries have left, too. The United States ran consistent trade surpluses in advanced technology products until China joined the World Trade Organization. In 2002, that surplus flipped to a deficit that in 2023 exceeded $200 billion, with the United States importing more than $3 of advanced tech products for every $2 it exported.

…

Committed to their discredited framework, economists continue to rely on the models built on it. The Peterson Institute, for instance, uses a model known as G-Cubed to predict that the United States would suffer higher prices, lower incomes and reduced manufacturing output if it withdrew the permanent normal trade relations granted to China in 2000. Economists have been using that model since the 1990s to produce studies guaranteeing that free trade will always work out well for all sides. The Budget Lab at Yale has produced its own negative assessments of Mr. Trump’s proposals using the Global Trade Analysis Project model, which one recent Federal Reserve study warned “had essentially zero predictive accuracy” in its efforts at forecasting results from previous trade deals.

Cass observes:

U.S. industrial output has, at best, remained flat since the mid-2000s, and workers in the manufacturing sector have been getting less productive for more than a decade.

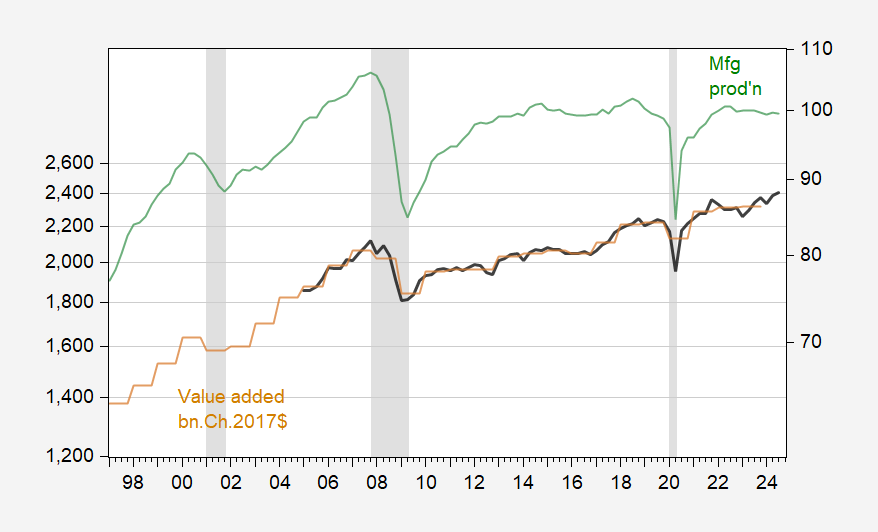

First, a point of fact, industrial production has been flat since the mid-2000s, but not necessarily value added. Here’s a comparison of manufacturing production and manufacturing value added.

Figure 1: Value added in manufacturing (black, left log scale), value added in manufacturing – annual – (tan, left log scale), both in bn.Ch.2017$ SAAR, manufacturing production (green, right log scale). NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA, Federal Reserve via FRED, NBER.

Second, regarding what models economists should use, I think Mr. Cass should’ve taken more than Econ 101. One of the first things I read when in grad school in international (around 1986 or so) wasF New Trade Theory, which focused on intra-industry trade, which is not based comparative advantage (see discussion of Krugman here; PA856 slides on monopolistic competition and trade; also Chapter 7 from Chinn-Irwin International Economics).

Third, Mr. Cass has focused on the deficit in advanced technology products. Indeed there is a widening deficit, as defined by the Census Bureau. In some circumstances, this could be considered an instance of revealed comparative advantage.

Figure 2: Advanced technology products exports (blue), imports (red), both twelve month trailing moving average, on log scale. NBER defined peak-to-trough recession dates shaded gray. Source: Census, NBER.

However, three points are useful to keep in mind: (1) imports are c.i.f.; exports are f.a.s.; (2) these are nominal values, and; (3) restrictions have been placed on exports, especially against those going to China (e.g., BIS)

In Mr. Cass’s indictment of trade theory, he (or his think tank) links to an argument for balanced trade – in Rebuilding American Capitalism.

Establish a uniform Global Tariff on all imports, set initially at 10% and adjusted automatically each year based on the trade deficit. After any year when the trade deficit has persisted, the tariff would increase by five percentage points for the following year. After any year when trade is in balance or surplus, the tariff would decline by five points the following year.

Of course, the target of balanced trade (if primary income and remittances quantitatively offset each other, as they do for the US) implies no intertemporal trade, which has clear negative welfare consequences.

In any case, it’s anything but clear that raising tariffs can alone zero out the trade deficit, unless they are sufficient to make trade entirely prohibitive (i.e., autarky). That’s because the trade balance (as opposed to the composition of trade) is driven by macro fundamentals, such as those that would be in the IMF macro balance approach — private saving, investment, and budget balance, demographics — and these are unlikely to be sufficiently altered to affect the trade deficit substantially (see Boz, Li, Zhang).

My plea: don’t criticize a corpus of literature if one isn’t familiar with the literature. (And for goodness’s sake read a textbook!)

Cass sounds like a anti-American. Anybody with brains knows American dollar globalism drives the trade deficit. Its a product of over consumption which is caused by excess dollars repatriated to the US. Debt markets over expand and consumption grows beyond its potential (about 1.2% real personal consumption). We saw during the financial crisis the trade deficit plunge???? Why did that happen Cass???

If you despise the United States. Just say so. Stop with the fake posturing. Decoupling will be ugly and a large part of the country will lose their jobs, farms, businesses. It will be 1930’s like.

I wonder if Cass is also a big fan of the Jones Act? That’s a banger policy that has persisted longer than lead in gasoline.

I recall we have been over Mr. Cass’s CV. He’s not quite a lawyer – attended law school but failed to graduate – and has an undergrad background in economics. So a lightweight, backed by a partisan institution. The partisan institution gets him a place in the NYT, yet another sign that the NYT ain’t what it once was.

Cass made a mess of his own argument, but even the terms of his argument weren’t adequate to condemn U.S. policy as it exists, and he didn’t really try to make an argument for tariffs. He made a flawed argument against free trade, then mumbled his way into claiming that means tariffs are OK.

Fredrick Pauper in the above comment has cut Cass through the jugular. I won’t take Pauper’s argument further. I will note, however, that there are other points to make against Cass. For one, the goal of trade ought not to be running a balance or a surplus, unless that balance improves the welfare of the population. If balance were the goal – everybody knows this one – autarchy would be dandy.

Here’s a sampling of GDP per capita, a rough approximation of welfare:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1Cu9p

Look who’s at the top of the heap. Does the U.S. have distributional problems? Yes. Do they invalidate the point that the U.S. is at the top of the heap? Here’s the same picture, with Georgia, among the poorest U.S. states, replacing the U.S.:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1Cu9D

Still top of the heap.

As to the stall in productivity gains, consider when it happened. Did factory productivity in the U.S. stall when China was admitted to the WTO? No, it stalled after the U.S. suffered a balance sheet shock in the Great Recession. Not every balance sheet shock is followed by stagnation in factory productivity – not in Japan, for instance – but it’s a better fit in the U.S. than China’s accession to the WTO.

Finally, let’s do what Cass has done; let’s take simple Econ 101 concepts and see where they lead. China has (had) cheap labor, the U.S. expensive labor. China had low capital intensity, the U.S. had high capital intensity. The simple 101 models predicts that low-productivity employment in the tradables sector would move to Japan. The result would be a rise in U.S. productivity in the tradables sector, as the composition of employment shifts toward higher-productivity jobs. Meanwhile, a shift from manufacturing to service production should lower overall productivity. Overall productivity has, in fact, risen pretty steadily:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/OPHNFB

Cass argues that a stall in factory productivity is evidence that trade has hurt the U.S. He has ignored the rise in overall productivity. His argument is simply a mess, any way you look at it.

I will not argue that free trade is the best policy to pursue, nor that our trade policy has done no harm. I only mean to argue that Mr. Cass is full of baloney. He hasn’t made his point and apparently doesn’t know how to make one. The NYT needs better editors.

Off topic – NY will force big greenhouse gas emitters to pay for remediation:

https://apnews.com/article/climate-change-damage-new-york-8afab2d111f71786e3d89c5326d2a4cf

Seems like a reasonable step. More needed.

Perhaps worth noting, Fitch and S&P have recently published reports on corporate default risk for 2025. Both note healthy balance sheets and the prospect of lower borrowing rates as reasons to expect low to moderate defaults on both corporate bonds and leveraged loans, with certain reservations; tariffs are cited as a risk to credit quality.

There’s no mystery in this worry over tariffs. Defaults happen when revenue doesn’t cover costs, and tariffs are a cost. This idea of adjusting tariffs in response to changing trade flows would make costs less certain, increasing credit risk, and so increase borrowing costs.