JW Mason asserts that, in focusing on the real exchange rate, I’m on the side of relative prices being the primary determinant of flows.

Here is one of the big cleavages between orthodox and (Post) Keynesian approaches to international economics: are trade flows mainly driven by relative prices, or by demand?

On the contrary, I think incomes are very important. This is demonstrated by my work on trade flows explained here. Updating, to 2024, I estimate for 1980-2024:

Δ exp t = β 0 + φ exp t-1 + β 1 y *t-1 + β 2 q t-1 + γ 1 Δ y *t + γ 2 Δq t + u t

Δ imp t = β 0 + φ imp t-1 + β 1 y t-1 + β 2 q t-1 + γ 1 Δy t + γ 2 Δq t + seven lags of Δq t + u t

Each error correction model specification includes a covid dummy (2020Q1-Q2) and first difference thereof.

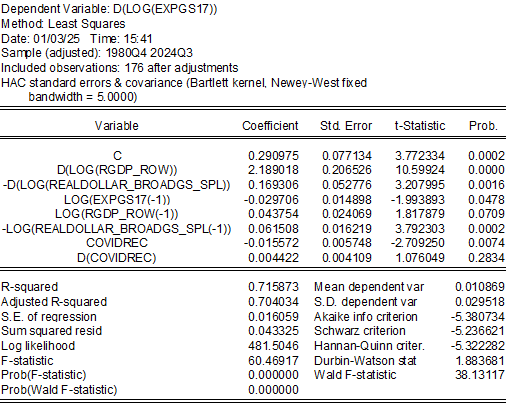

For US exports of goods and services:

This implies the long run elasticity of exports with respect to the dollar exchange rate is 2.07, while that of income (rest-of-world trade-weighted GDP) is 1.47.

This compares with a 2.3 and 1.9 as found in Chinn (2004).

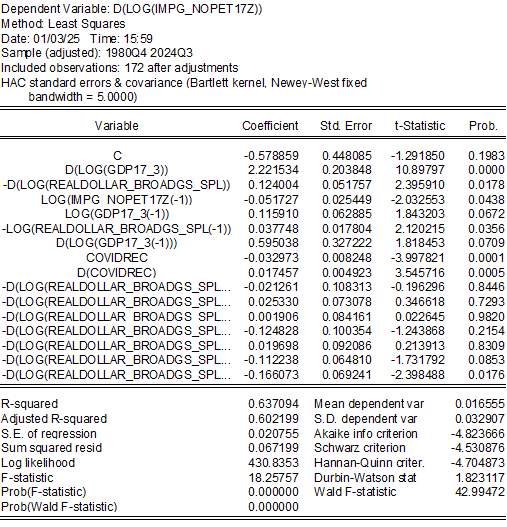

For goods imports, the real exchange rate is important as well, although it’s more difficult to obtain a statistically significant estimates.

The long lags in the exchange rate are consistent with numerous studies indicating that the effects of the exchange rate take a long time to have an effect (it’s consistent with the graph in this post).

The long run elasticity of goods imports (ex-oil) with respect to the dollar is 0.74, and with respect to US income is 2.24.

In Chinn (2004), I obtain long run estimates of -0.2 and 2.3 for total imports, respectively. In Chinn (2010), I obtain estimates of -0.5 and 2.2 respectively, for ex-petroleum goods imports, for data up to 2010.

Hence, income is important, as are relative prices. I think of this as a conventional view (see e.g., Rose and Yellen, JME 1989), rather than orthodox vs. post-Keynesian view.

Now, as for relative importance, one can look at standardized (or “beta”) coefficients, which are OLS coefficients divided and multiplied standard deviations. For an exports regression estimated in first differences, the income “beta” coefficient is about four times the size of that for the exchange rate. For the non-oil goods import first differences equation, the income “beta” coefficient is about ten times that of the exchange rate coefficient.

This is a breath of fresh air – a real economist commenting on the work of a real economist. Even so, there is room for misconstruing the other guy’s thinking.

Take, for instance, Mason’s demonstration that two unrelated series can be made to seem correlated. Is that really a good way to criticize Menzie’s comparison of two series which have a strong theoretical connection? Mason then shows that imports and export vary together, claiming that is evidence against relative prices driving trade flows. Is that really true, in a world full of intermediate goods trade? In a world of intermediate goods flows, wouldn’t we expect to see imports and exports vary together, even if driven by relative prices? Menzie used net exports, rather than the input series of imports and exports. If Mason had looked at net exports, would he have come to a different conclusion?

I also wonder whether insisting on a choice between relative prices and demand isn’t a false dichotomy. I think the world is more complex than that. I think, rather than “this or that”, we are discussing a world of “this AND that” when it comes to trade flows. Mason’s position seems to be that net imports respond to demand, without regard to price. That may be true in the short term, but seems a truly odd view of how things work in the longer term.

Maybe I’m just hung up on 101 – supply, demand, qualtity and price.

If Mason means to argue that demand matters more than relative prices, rather than that demand is all that matters, is he right? Menzie finds that the coefficients for income (demand) are larger than those for exchange rates would suggest that’s right, if it weren’t for one thing:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1CD48

Exchange rate variability is far greater than income variability. So, stronger coefficient for income, higher variability for exchange rates. Which one has the stronger influence over actual trade flows is a math question.

Macroduck: That’s why I referenced the “beta” coefficients; define beta* = beta(sx/sy), where beta is the OLS coefficient, and sx is the standard deviation of the X variable.

Ah. So Mason is off the hook…on that point.

I stand corrected! My apologies, and thanks for this helpful post.