Today, we present a guest post written by Jeffrey Frankel, Harpel Professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, and formerly a member of the White House Council of Economic Advisers. A shorter version appeared in Project Syndicate.

Category Archives: international

Trade Deficit Rising!

Since 2017Q1. By Mr. Trump’s own metric, we’re losing. But it’s a stoopid metric for evaluating “unfair”-ness.

A Reminder of Why It’s the G-7 and Not G-8

And also why we have sanctions against several Russian citizens, firms and financial institutions. Hint: It has something to do with the orange areas:

Source: Euromaidenpress.

EconoFact: “What is the National Security Rationale for Steel, Aluminum and Automobile Protection?”

From EconoFact, an update:

The Trump administration has implemented a number of trade related measures purportedly on the basis of national security. First, it invoked the seldom-used provision of the trade law to investigate whether imposing import restrictions for steel and aluminum is justified by national security reasons. The Commerce Department’s investigation concluded that imports of both metals pose a national security risk and subsequently the administration applied tariffs and quotas to both products. In a new investigation, the Commerce Department has started looking into whether imports of cars or automobile parts could impair U.S. national security.

Guest Contribution: “Trump’s On-Again Off-Again Trade War with China”

Today, we present a guest post written by Jeffrey Frankel, Harpel Professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, and formerly a member of the White House Council of Economic Advisers. An earlier version appeared in The Hill.

Long Horizon Uncovered Interest Parity, Updated

About twenty years ago, while visiting the Research Department of the IMF, Guy Meredith poked his head in my office and wondered aloud whether interest differentials could reliably predict (in the right direction) subsequent exchange rate changes at horizons of three to five years. The resulting paper led in turn to production of this graph:

Figure 1: Panel beta coefficients at different horizons. Notes: up to 12 months, panel estimates for 6 currencies against US$, euro deposit rates, 1980Q1-2000Q4; 3-year results are zero-coupon yields, 1976Q1-1999Q2; 5 and 10 years, constant yields to maturity, 1980Q1-2000Q4 and 1983Q1-2000Q4 (last observation corresponds to exchange rate data). Source: Chinn (2006).

Guest Contribution: “Exchange rate forecasting on a napkin”

Today we are fortunate to present a guest post written by Michele Ca’ Zorzi (ECB) and Michal Rubaszek (SGH Warsaw School of Economics). The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the ECB.

We have just released a new ECB Working Paper entitled “Exchange rate forecasting on a napkin”. The title highlights our desire to go back to basics on the topic of exchange rate forecasting, after a work-intensive attempt to beat the random walk (RW) with sophisticated structural models (“Exchange rate forecasting with DSGE models,”).

Tales from the Midwest (Macro Spring Meetings, That Is)

Program here. Here are a couple of papers I found of interest.

From the Empirical Macro session:

- “Output response to government spending: Evidence from new international military spending data,” By Viacheslav Sheremirov; Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Sandra Spirovska; University of Wisconsin, Madison

Using 25 years of military spending data from more than a hundred countries, this paper provides new evidence on the effect of government spending on output. Following a popular assumption that military spending is unlikely to respond to output at business-cycle frequencies—and exploiting variation in military spending of a significantly larger magnitude than in the previous literature based on U.S. data—we find that the pooled government spending multiplier is small: below 0.2. This estimate, however, masks substantial heterogeneity: the debt financed

spending multiplier is larger and can be well above 1 if monetary policy is accommodative. The multiplier is especially large in recessions and when the government purchases durables. e also document substantial heterogeneity across countries with the spending multiplier larger in advanced economies and in countries with a fixed exchange rate. The output response to government spending persists for about two to three years. These findings suggest that the effectiveness of fiscal policy depends largely on the economic environment, policy implementation, and the central bank’s response, and that the small multipliers found in historical or pooled data are a poor guide to evaluating the effectiveness of a specific stimulus program.

From the Monetary Policy session:

- “Has Globalization Changed the Business Cycle and the Monetary Policy Trade-offs?” by Enrique Martinez-Garcia; Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

No presentation/paper online, but the answer is “yes”.

Tomorrow, there’s the Sovereign Debt session:

- “Optimal Redistributive Policy in Debt Constrained Economies,” by Monica Tran Xuan; University of Minnesota

This paper studies optimal taxation in an open economy subject to redistribution motive and long-run binding debt constraints. The debt constraints arise endogenously from the government’s limited commitment, and become relevant in the long run due to the impatience of the domestic agents. Marginal and lump-sum taxes are allowed to distribute resources across heterogeneous agents. The standard Ramsey results of labor tax smoothing and zero capital tax limit no long hold. The optimal labor tax decreases as the debt constraints bind, and eventually converges to a real limit. The optimal capital tax is positive in the long run. The effcient contract features front-loading redistribution and back-loading efficiency, allowing the economy to accumulate a large external debt position, and increase its borrowing capacity when the debt constraints bind. A numerical exercise of the model demonstrates that a higher redistribution motive leads to a higher labor tax rate during the unconstrained-debt periods, a lower labor tax limit, and a higher external debt accumulation over time.

- “Sovereign Risk Premia and Corporate Balance Sheets,” by Steve Pak Yeung Wu; UW-Madison

- “Real Interest Rates and Productivity in Small Open Economies,” by Tommaso Monacelli; Università Bocconi and IGIER; Luca Sala; Universita’ Bocconi; Daniele Siena; Banque de France

In emerging market economies (EMEs), capital inflows are associated to productivity booms. However, the experience of advanced small open economies (AEs), like the ones of the Euro Area periphery, points to the opposite, i.e., capital inflows lead to lower productivity, possibly due to capital misallocation. We measure capital flow shocks as (exogenous) variations in (world) real interest rates. We show that, in the data, the misallocation narrative fits the evidence only for AEs: lower real interest rates lead to lower productivity in AEs, whereas the opposite holds for EMEs. We build a business cycle model with firms’ heterogeneity, financial imperfections and endogenous productivity. The model combines a misallocation effect, stemming from capital inflows, with an original sin effect, whereby capital inflows, via a real exchange rate appreciation, affect the borrowing ability of the incumbent, marginally more productive firms. The estimation of the model reveals that a low trade elasticity combined with high (low) firms’ productivity disperions in EMEs (AEs) are crucial ingredients to account for the different effects of capital inflows across groups of countries. The relative balance of the misallocation and the original sin effect is able to simultaneously rationalize the evidence in both EMEs and AEs.

If ZTE Sanctions Are Up For Grabs, What about Additional Section 301 Sanctions?

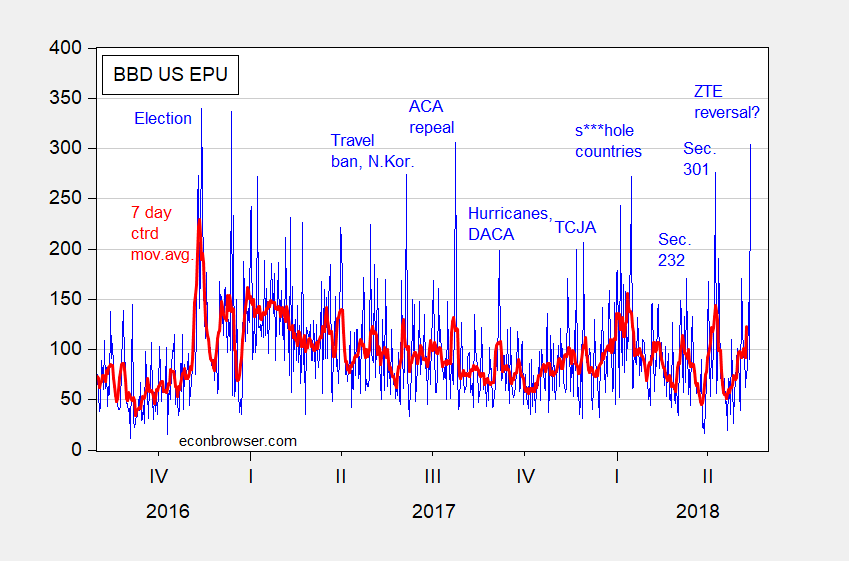

Economic policy uncertainty as measured by the Baker, Bloom and Davis index is elevated (again) due to trade policy.

Figure 1: US Economic Policy Uncertainty index (blue) and centered 7-day moving average (bold red). Source: policyuncertainty.com accessed 14 May 2018, and author’s calculations.

Mr. Trump’s Faux National Security-based Trade Policy (aka ZTE – WTF?)

or, Mr. Trump is a wimp

President Xi of China, and I, are working together to give massive Chinese phone company, ZTE, a way to get back into business, fast. Too many jobs in China lost. Commerce Department has been instructed to get it done!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) May 13, 2018