No more military Keynesianism after G.W. Bush?

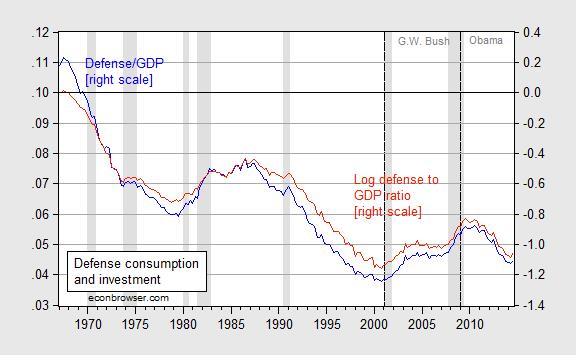

It is one of the strange paradoxes that those who disbelieve that government spending can stimulate the economy are sometimes the same individuals that believe reduced defense spending can decrease economic activity. (G.W. Bush is not subject to this criticism; see [1].) Well, internal consistency has not always been a strong suit for some. What is interesting is that, proportionately, spending on national defense has declined substantially; my view is that this has resulted in some drag in growth. Figure 1 shows the trends in defense expenditures (on consumption and investment).

Figure 1: Nominal defense consumption and investment as a share of nominal GDP (blue line, left scale), and log ratio of real defense spending to real GDP, 1967Q1=0 (red line, right scale). NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA 2014Q3 2nd release, NBER, and author’s calculations.

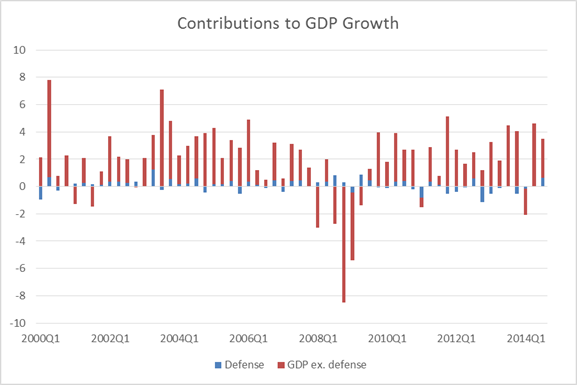

An accounting decomposition of expenditure contributions of defense consumption and investment confirms the net deduction from that category.

Figure 2: Contribution to GDP growth of defense (blue), of GDP ex.-defense (orange), q/q SAAR, %. Source: BEA 2014Q3 2nd release, and author’s calculations.

Of course, this is just an accounting decomposition. In economic terms, defense spending would account for even more if the multiplier for defense consumption and investment expenditures is greater than that for civilian spending (possible) and transfers (likely). One estimate of the defense spending multiplier is 1.5 [2] (See a discussion of military Keynesianism back in 2007 here).

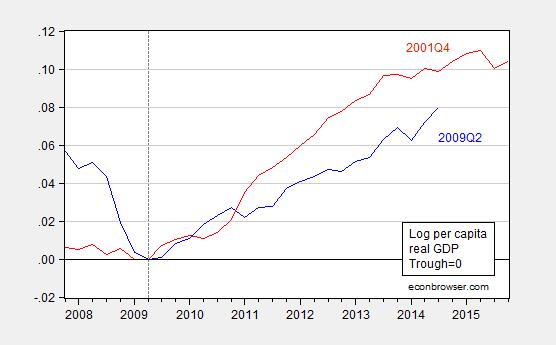

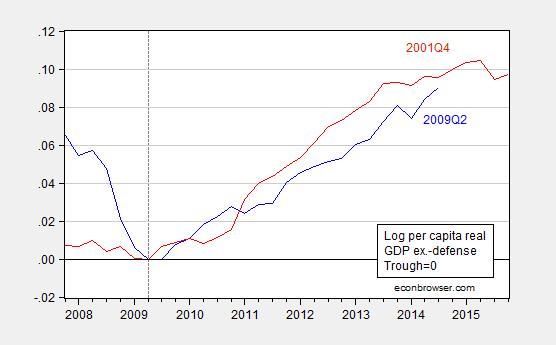

Taking into account this trend makes the current recovery look much better as compared to the previous. Here I take a normative stand — that defense expenditures might have a different weight in aggregate welfare than non-defense. Figures 3 and 4 depict trends in output and output ex.-defense consumption and investment, for the current (blue) and previous (red) recoveries.

Figure 3: Log per capita real GDP normalized to zero at trough at 2009Q2 (blue), at 2001Q4 (red). Source: BEA 2014Q3 2nd release, and author’s calculations.

Figure 4: Log per capita real GDP ex.-defense normalized to zero at trough at 2009Q2 (blue), at 2001Q4 (red). GDP ex.-defense calculated using Törnqvist approximation. Source: BEA 2014Q3 2nd release, and author’s calculations.

The cumulative growth in per capita output is 1.9% less than that at the corresponding point in the previous recovery. But taking out defense spending (once again in an accounting sense), one finds that the gap is only half a percentage point. Taking into account multiplier effects would likely shrink the gap. (Note: the GDP ex.-defense variable can not be calculated by simply subtracting the Chain weighted defense consumption and investment from Chain weighted GDP; see this post.)

The foregoing not an argument for more defense spending — especially misdirected spending [3] [4]. Rather, it’s another reason for why the recovery has been so slow (in addition to the contractionary impact of state and local level government spending. [5] [6])

Barry Riholtz disagrees:

http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/2014/12/debunking-the-myth-war-is-bad-for-the-economy/

(While the title to his post is “War is Bad for the Economy”, his arguments and most of the authorities cited (right and left) refer to government spending on the military and not war per se).

Vivian Darkbloom wrote: “While the title to his post is “War is Bad for the Economy”, his arguments and most of the authorities cited (right and left) refer to government spending on the military and not war per se.”

This is an contradiction in itself. Maintaining armed forces is very unproductive in most times. However, you may gain a real benefit when you destroy an economic competitor, acquire a market a or secure important resources. However, this is more or less war. Here WWII shines for the USA on more than one front. : 🙂

(An alternative business model in history was to provide security and let other pay or coerce other to pay.)

The current problem of the USA is IMHO that without sound business model, e.g. good grand strategy in contrast to the current dysfunctional foreign politics, the level of US miltary spending is contraproductive: the options the US armed forces “obviously” offer allow bad political decisions like Afghanistan (after 2001) and Iraq 2003; Lybia and Syria are bunders too. The damage of these decisions is even higher than an unused military.

The little gedankenexperiment would be to spend 4000 billion USD, let’s say 200 billion per year, on civilian infrastructure, alternative energy, education .

Could an military approach compete?

In an ideal world, the right amount of spending on defense is zero.

Now, if you don’t live in an ideal world, then it’s trickier. In a democracy, defense–like security and police spending–is about avoiding a loss rather than achieving a gain. It is the functional equivalent of a goalie, where success is measured entirely in Type II errors (things we should have done, but didn’t). It is not amenable to traditional analysis, as the entire value must be calculated in counter-factuals.

However, if you’re using defense spending to stimulate the economy, that’s wrong, dead, absolutely wrong. If you want to stimulate the economy, implement a tax cut. That money will be well spent. Defense spending, just to spend money, is a bad idea and a waste of resources.

A tax cut? No. The balanced budget multiplier is positive, so the better use of fiscal policy is a spending increase. We have large needs for public spending. The record for the expansionary effect of tax cuts at current rates is very poor.

It is hard to imagine an evidence-based argument for broad tax cuts as a means of economic stimulus.

Should a government aid in deleveraging at crisis points? There is a case to do so.

Does the US need that now? US consumers have begun to lever up again, so the answer is no.

Have you been over to CR lately? ISM Non-Manufacturing Index is at the highest level in the historical record (since 1998)

Read more at http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2014/12/ism-non-manufacturing-index-increased.html#CP2WFVFPKAepzJKs.99

On labor markets, Mark Zandi, chief economist of Moody’s Analytics, said, “Steady as she goes in the job market. Monthly job gains remain consistently over 200,000. At this pace the unemployment rate will drop by half a percentage point per annum. The tightening in the job market will soon prompt acceleration in wage growth.” Whom did you hear that from first?

Read more at http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/#YcPUTzgeURDIjFCe.99

Car sales posted their fourth best month since 2006.

What is the problem you’re trying to solve?

This economy needs nothing right now but to stay on trend.

Is there a multiplier on deficit spending? I couldn’t find one: http://www.prienga.com/blog/2014/11/28/deficit-spending-and-gdp-growth

steven

” If you want to stimulate the economy, implement a tax cut. That money will be well spent. ”

really? if you get an extra $5000 back in your taxes, what will you do with it? mine goes into savings, and i imagine yours does as well. currently most new tax cuts go to people who do not need the extra money on day to day living-so it is not spent. collected taxes are however spent. now if you are willing to target your tax cuts to a selection of the population, that is a different story. but you need to target the correct people-something we have not done very well when tax cuts are implemented.

Yes, fine, Baffs. I am saying that DoD ordering another fighter jet or carrier group, unless it’s actually needed for defense, is a waste of money. I would rather see that sum spent on education, healthcare, or simply giving it to households by whatever criteria you care to use.

steven,

” or simply giving it to households by whatever criteria you care to use.”

i think we are in agreement as long as you are particular to which households get that money back. the problem with supporting tax cuts is you get undermined by a faction who feel tax cuts should be everywhere for everyone. but those are not stimulus based cuts. the cuts need to be targeted to people who will actually spend the money. again, you and i are in agreement, but do not let a select group of folks take your words and bully them into what you did not mean. i don’t think you believe tax cuts in general are a stimulus. i think you mean well targeted tax cuts are a stimulus-and that target does not include the well off.

A little, or a lot, off topic, but did anyone see Krugman’s seemingly pro-libertarian blog post today? He essentially asks the question, “What was Obama supposed to do to focus more on the economy? Squint at it?”. This is what economic conservatives have said all along: the government is terrible at fixing economies, and therefore government officials should in fact just squint at the economy from afar. I am not making a case against stimulus here, which is something done on the margin and very temporary. I am saying that the government is terrible at fixing economies as a whole. Liberals like Krugman are the ones that are usually saying the government should take over Wall St banks (which he made the case for during the deepest parts of the recession, which is totally insane), increase taxes, etc. Overall, the US is a great country because we have limited regulations. Or, essentially, because presidents in the US have in fact just squinted at the economy for centuries now, which is an awesome thing and exactly what economic conservative believe should occur.

Actually, Republicans argued at the time Obamacare was passed the he should have focused on the economy. This was at the same time that they argued for deficit cuts. The GOP “focus” argument rarely included actual proposals. Didn’t need to. It worked well enough that Democrats repeated it then, and at least one prominent Democrat is still repeating it now.

When challenged to offer details, they coughed up the same old stuff – tax cuts and deregulation.

Obama’s mistake was not putting universal coverage ahead of the economy. It was trying to placate Republicans who continued to obstruct any policy he offered. Their aim was making Obama look bad to the public, no matter the cost. Same as it was with the first Clinton, and very well could be with the next one.

I agree. Republicans and Democrats at the end of the day are both politically motivated and their incentives are not always aligned with improving the economy. This supports a Libertarian’s view (not necessarily a Republican view, even though most Republicans in office are likely slightly more free-market based than Democrats, except of course for one of the biggest issues which is opening up the borders to free labor mobility) that government officials, whose primary goal is to be re-elected, should probably stay at an arms lenght distance from any major meddling in the economy. Or, as Krugman put it, it is a good thing when they simply squint at the economy from afar.

When it comes to stimulus, Menzie has robustly shown that stimulus is in fact stimulus and does help the economy. However, there are still massive costs (not just monetary costs) to stimulus which makes the argument that the economic benefits outweigh the economic costs almost impossible to definitively agree or disagree with. Therefore, and I think Menzie is right to do this, sometimes to get over the hump of the cost/benefit analysis, liberals appeal to the moral side of things (stimulus is paid for by higher-earning taxpayers, and the benefits go to poorer people), so it is easier for people to swallow the pill that there is a transfer of wealth from people that earned their money to people that are not earning their money. But stimulus is only one very small part of the US economy, even during recessions, and the laws and regulations that the government has in place in the US are good overall, and that is because Republicans/Conservatives fear government intervention and overregulation and therefore make any even small change to US laws or regulations very difficult to make.

Except the Republicans and the First Clinton got some very important legislations passed. The US prospered under Clinton more than under any other President since, perhaps, Kennedy. Govt spending as a share of GDP fell, and the budget was balanced. Let’s do that again.

steven, was the balanced budget the reason for clinton’s success, or the result of his successful policies?

The balanced budget was the result of successful Clinton-era policies.

By the way, Bush blew that surplus in a hurry. Some of us remember that. Part of the reason the Tea Party exists.

1. How much of the decline in defense spending is money not spent overseas? In other words, we spend money here and we spend money somewhere else and we’ve wound down our activities elsewhere. I’m not talking about vehicles built here and left in Iraq but we spent a lot of money in Iraq and Afghanistan. I would think the multiplier on that money might be less than 1. It’s hard to find this information.

2. Some of our defense spending is investment. (Which is one reason I pay little attention to so-called $600 hammers whose price is determined by allocating the entire budget across the physical items.) It’s hard to determine how much is investment and then, frankly, how much is necessary just to maintain the production pipeline for our defense. An example: people don’t get that big chunks of foreign aid are actually credits held in the US and paid out to the US defense industry. That extra production is necessary to lower unit costs for our forces, to keep production moving and to project our influence and to keep competitors from growing into the foreign niches we abandon if we produce only for ourselves. It’s hard to price those last two and I have no idea how one could attach a multiplier to those, which means a multiplier for defense spending as a whole is misleading.

Good post Menzie.

Military expenditure (MILEX) multipliers do have the potential to exhibit a greater magnitude than civilian expenditures because the market is protected and most expenditures are directed to domestic purchases thereby minimizing leakages.

As for the ‘productivity’ of MILEX, that depends on policy. It would appear that the invasion and occupation of not but two Mid-East/Near East countries certainly confirmed the US status as powerful terrorist state but given the context of the early 21st century, righteous US terrorism appears to work against western diplomatic, security and economic goals.

In the background, US aid to Israel and US support for Israel’s nuclear weapons back affirmative action ethnic cleansing program is constant.

If I did not know any better, I would say that Americans either enjoyed the Sept. 11th attacks or at least exhibit a high willingness to pay (in economic wealth and American blood) for Israeli nation building.

It’s important to recognize that DoD is unique among federal agencies in that it has five different budgetary subfunctions, each with its own rules regarding the life of the budget authorization. The categories with the biggest fiscal bang for the buck are in the military personnel subfunction and operations & maintenance (O&M). Both of those must be “obligated” (i.e., put on contract) in the current fiscal year. The law does allow five additional years for actual disbursement (i.e., when the Treasury actually cuts the check), but most aggregate demand stimulus comes when the contract or work order is awarded and not when Treasury pays. Of course, our NIPA tables don’t pick this up because DoD’s contribution to NIPA is based on Treasury disbursements rather than budget authorizations or contract awards. So it’s no wonder that many academic studies are not able to detect any multiplier from DoD spending. The other subfunctions are RDT&E (with a slightly longer authorization life), military construction (five years to obligate plus another five years to disburse), and procurement appropriations (PA). The PA authorizations have to be put on contract within 3 years of the budget authorization year, except for ships and fixed wing aircraft, which get a five year life. All PA buys also have an additional five year disbursement life. So obviously deciding to buy more tanks and ships and fighter aircraft has very little fiscal punch because of the long lag between when Congress authorizes the procurement and when the contract is actually awarded (up to 3 or 5 years) plus actual disbursements.

On a personal note, shortly after Obama’s 2008 election victory I was invited to a participate in a brainstorming project that would dream up ways to use military spending as part of the ARRA. Those with long memories might recall a WSJ op-ed piece that Marty Feldstein wrote at the time. Feldstein used the op-ed as an opportunity to push for spending on aircraft, ships, and other weapon systems….all of which are procured using PA dollars, which have almost no fiscal punch. I dissented and argued for increased OMA spending (hey…we certainly had plenty of shot up equipment that needed to be repaired). My recommendations fell on deaf ears because it wasn’t what leadership wanted to hear. So I bailed and went back to more productive efforts.

Some defense spending has massive economic multipliers (e.g., GPS), while others less so (army surplus).

The problem is that it is difficult to separate policy spending (we’ve got to get rid of Assad/Hussein/Mubarek/Qaddafi/Taliban/Al Qaeda) versus military spending to remain a formidable foe against potential adversaries who are spending increasing amounts on military expansionism (China/Russia).

Bruce Hall Some defense spending has massive economic multipliers (e.g., GPS), while others less so (army surplus).

It sounds like you might be confusing fiscal multipliers and technological advances that lead to spillover growth. Menzie is talking about fiscal multipliers, which is a very different concept. BTW, army surplus would not count as a change in GDP because it was not produced in the current period. Materiel that is surplus today was counted in some previous year’s GDP.

2slug, you are correct. I lumped all economic benefits of military spending in one bucket which is probably not too unreasonable. But I recognize that makes specific identification of expansion related to a specific sum spent in a specific time/place. Nevertheless, ignoring those benefits leads to false assumptions about the value of military spending in economic growth.

“But I recognize that makes specific identification of expansion related to a specific sum spent in a specific time/place” difficult.

The boost in government spending, along with the small and slow tax cuts, failed to jolt the economy into a self-sustaining consumption-employment cycle.

When there’s a mountain of household debt, after a long period of overconsumption, watching your $5,000 tax cut go into a few toilet seats for the defense department won’t help you much.

And, there’s nothing wrong with some saving, e.g. for retirement, a down-payment on a house, sending your kid to Harvard, creating a scholarship for a poor kid, etc..

We need more spending & saving and less squandering.

We need more spending & saving and less squandering.

Huh??? How do you simultaneously increase both spending and saving?

there’s nothing wrong with some saving

But if you want to increase private saving during a recession…say because households need to repair balance sheets and deleverage debt, then someone or some entity has to be willing to borrow that savings. If no one or no entity is willing to borrow that additional private saving, then you’re basically just shoving money in the proverbial mattress. During the Great Recession no private entities wanted to borrow. That left the government as the borrower of last resort. The government’s borrowing creates a deficit on one side of the ledger, but it also creates a financial asset on the other side of the ledger. The lesson that Keynes taught us and that too many economists seem to have forgotten is that for every dollar saved there has to be someone willing to borrow that dollar; otherwise money leaks out of the system

Income = consumption + saving.

Cutting taxes raises disposable income.

And, households paying-down debt raises discretionary income.

Also, I stated before, U.S. consumers bought foreign goods and foreigners bought U.S. Treasury bonds. Not enough of those dollars were “refunded” to consumers to allow the spending to go on.

Generating demand through lower taxes, along with lower interest rates and lower prices, cause people to spend more and save less.

The U.S. economy has changed, since the Great Depression, when taxes were low and government spending was needed.

peak

“And, households paying-down debt raises discretionary income.”

it only raises discretionary income after the debt has been paid down. for most folks, do they ever reach the point where the debt is paid off so the money is turned into discretionary income? sounds great in theory, but in practice i don’t think the model you assume actually exists.

so the question really becomes, when you cut taxes how much of it is put back into circulation? as we have discussed on this blog before with steven, you need very targeted tax cuts. the wealthy do not “spend” that money-they already have plenty of disposable income. tax cuts need to go to the right people-they are not effective when broadly based or focused on the wealthy. a tax dollar collected is however spent on the economy.

My proposal was a $5,000 tax cut per worker, or $700 billion for the 140 million workers at the time.

Each worker will use their tax refund the best way they see fit. Some will pay-off a car loan (most workers drive to and from work), others will pay-off credit cards (and likely use them again, because people with credit cards are more likely to spend), some will catch-up on bills, some will spend it all, some will invest it all (in the stock market or a business), some will donate it all, etc..

It’s a regressive tax refund. A part-time worker may receive a $5,000 tax credit, while a full-time worker pays $5,000 less in taxes. Would it be fair to expect workers paying the most in taxes to receive nothing?

This article offers a rare example of claims which systematically contradict both observed evidence, theory, and currently reported events. As such, this article represents a true trifecta of error — it’s wrong in every possible way.

Let’s start with the observed evidence. That’s in. A 2009 study has shown that the multiplier of U.S. military spending is significantly lower than the multiplier of non-defense spending:

“Study: Federal Spending on Defense Doesn’t Create As Many Jobs As Education Spending” TIME magazine, 21 September 2011.

Link to the 2009 study here.

The multiplier turns out to be dramatic. Education spending produces as much as twice as many jobs per dollar as military spending. The knock-on effects of jobs created, of course, produces increased aggregate demand and resultant increases in GDP. So military spending turns out to do an excellent job of reducing overall aggregate demand and GDP compared to other forms of government spending.

So much for observed reality.

But military Keyensianism also suffers from severe theoretical problems, as pointed out by Seymour Melman:

As recent studies have shown, rising monopoly power in industry produced increasing inequality which in turn results in decreasing GDP growth. There’s no better recipe for riding monopoly power in industry than the consolidation of vast conglomerates into defense industry monopolies which enjoy the unparallelled capacity to extract limitless rents from the government in return for continuing the only available source of, viz., F-35 fighters (now some several trillion dollars over budget and continuing to explode in cost, yet still in production despite the procurement debacle). This leads (obviously) to ever-increasing inequality in American society, with the parasite defense contractors and their hangers-on growing wealthy while the other U.S. industries collapse and starve — which in turns leads to ever-decreasing GDP growth, as rising inequality is wont to do.

So much for the theoretical pitfalls of military Keynesianism.

Let’s now examine news reports on Hilary Clinton’s military spending policies. As the presumptive 2016 presidential candidate (and, given the overt lunacy of the likely Republican nominees like Rand Paul and Ted Crus, the likely next president), her reported position on military spending gives us a glimpse of the probable future direction of U.S. military spending:

“The Military-Industrial Candidate: Hillary Clinton prepares to launch the most formidable hawkish presidential campaign in a generation.”