I have been stressing the international implications of a potential interest rate increase as a rationale for deferring monetary tightening. Export growth is slowing and economic activity in the tradables sector (manufacturing output, manufacturing employment) as the dollar has appreciated. [1] [2] How much more appreciation should we expect should the Fed tighten?

This is actually a harder question to answer than one would think. That’s because over the past seven years, the correlation between the US short term interest rate and the dollar has essentially disappeared as the zero lower bound has placed a floor on rates. This point is illustrated in Figure 1.

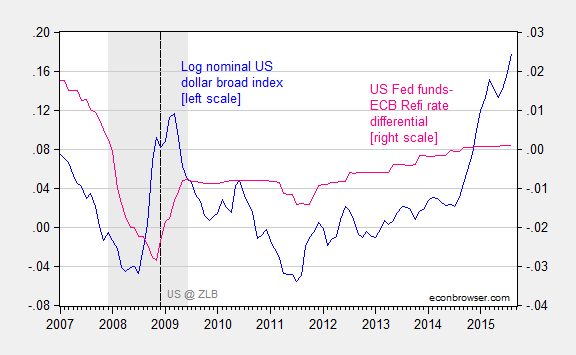

Figure 1: Log nominal USD broad index, 1973M01=0 (blue, left scale), and Fed funds – ECB refinance rate differential (pink, right scale). An increase in the log USD index from 0.021 to 0.178 implies a 15.7% appreciation. NBER Defined recession dates shaded gray. Dashed line at 2008M12 when ZLB effectively encountered. Source: Federal Reserve Board, Bundesbank, NBER, and author’s calculations.

A regression (in first differences) over the 199M03-2015M08 period yields a statistically insignificant negative coefficient on the interest differential, with zero adjusted R-squared. Augmenting with VIX leads to an increase of adjusted R-squared to 0.15, but no change in the coefficient on the interest differential (the explanatory power is provided by the VIX).

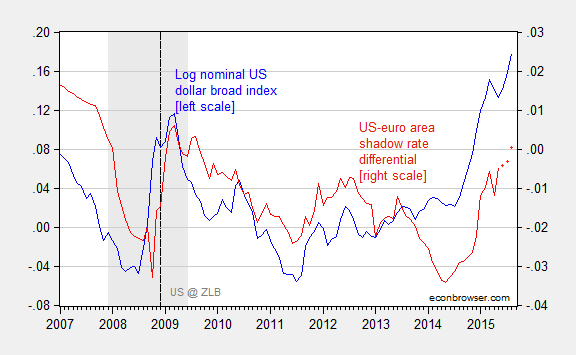

As I’ve pointed out before, the US dollar does seem to be correlated with the shadow Fed funds rate. Without a good measure of rest-of-world interest rates, I use the shadow rate for the euro area. Both series are calculated by Wu and Xia.

Figure 2: Log nominal USD broad index, 1973M01=0 (blue, left scale), and shadow Fed funds – shadow ECB rate differential (red, right scale). An increase in the log USD index from 0.021 to 0.178 implies a 15.7% appreciation. 2015M06-09 differential observations assume ECB shadow rate at 2015M05 level. NBER Defined recession dates shaded gray. Dashed line at 2008M12 when ZLB effectively encountered. Observations for differential for 2015M06-09 are based on no-change in ECB shadow rate from 2015M05. Source: Federal Reserve Board, Wu and Xia, NBER, and author’s calculations.

Running a regression over the 1999M03-2015M05, in first differences, yields:

Δet = 0.0002 + 0.636Δ(it-it*) + 0.114ΔVIXt + 0.630Δ(it-1-it-1*) + 0.074ΔVIXt-1 + ut

Adj-R2 = 0.26, SER = 0.010, Nobs = 195, DW = 1.34. bold face denotes statistical significance at the 10% msl using HAC robust standard errors.

These results are intuitive; increases in the interest rate result in strengthening of the currency (as in the Dornbusch Frankel model). An increase in the VIX also strengthens the dollar, which is consistent with the safe haven role of the US dollar.

These results indicate that each a 1 percentage point increase in the shadow rate differential results in a 1.3 percent increase in the nominal value of the dollar. There is some reason to believe that the actual impact is larger.

First, given that shadow rates are estimated, the true shadow rates are probably measured with error, biasing downward the OLS point estimates. Second, the long run impact is probably not accurately measured by the coefficients on the included lags. Second, augmenting the specification with a lagged dependent variable yields a coefficient of 0.3; if one were to accept the common factor restriction, this implies the (statistical) long run impact of higher interest rates is closer to 1.9 (which is the coefficient obtained by a regression in levels).

Over the period of the ZLB (2008M12-2015M05), the fit is even better:

Δet = 0.0014 + 1.550Δ(it-it*) + 0.121ΔVIXt + 0.818Δ(it-1-it-1*) + 0.090ΔVIXt-1 + ut

Adj-R2 = 0.52, SER = 0.008, Nobs = 78, DW = 1.54. bold face denotes statistical significance at the 10% msl using HAC robust standard errors.

The cumulative impact of a one percentage point interest rate increase is 2.33.

If markets behave in the wake of liftoff as they have during the last six years, then a literal interpretation of the results suggests a 25 basis points increase will induce 0.6 percent appreciation of the nominal broad-currency-basket dollar index.

Of course, the interpretation of what would happen if the Fed were to raise the Fed funds rate to 0.25 to the interest differential is open. At the end of August, the shadow Fed funds rate was -0.92%. The effective Fed funds rate is now 15 bps, so an increase of 25 bps to 40 bps would mean an increase of about 1.3 percentage points. That means about a 3% increase in the trade weighted dollar (3.6% for the major-currency-basket dollar index).

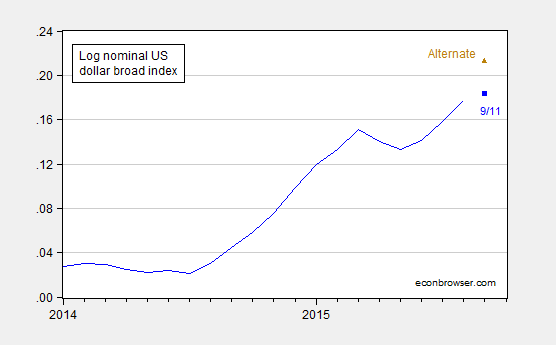

Figure 3: Log nominal USD broad index, 1973M01=0 (blue), observation for 9/11 (blue square), and alternative under assumption of increase of Fed funds target to 40 bps (brown triangle). An increase in the log USD index from 0.021 to 0.178 implies a 15.7% appreciation. 2015M06-09 differential observations assume ECB shadow rate at 2015M05 level. Source: Federal Reserve Board, Wu and Xia, NBER, and author’s calculations.

Is this a big impact? Since the standard deviation of dollar changes is about 1.2% (2008M12-2015M08), it’s certainly noticeable. And I think undesirable for US economic activity at this juncture.

In addition to the effects on the US economy, the stronger dollar on top of a higher Fed funds rate will have measurable effects on emerging markets, as documented here (see analysis here).

Update, 8am Pacific 9/16: See also World Bank, “The Coming U.S. Interest Rate Tightening Cycle: Smooth Sailing or Stormy Waters?” Policy Research Note No.2: .

I think the organic dollar appreciation resulting from increased shale output is ebbing. Lower 48 crude production is falling at the pace of 100 kbpd / month, which is phenomenally fast. This will translate into a deteriorating trade balance, first due to volumes, and later due to increasing oil prices. From the oil perspective, pressure on the dollar has already turned negative, and will be materially more so over the next six months,

I accept the argument that there’s no inflation and that, even now, the economy doesn’t seem quite normal. On the other hand, interest rates are at historical lows and JOLTS tells us we’ve about used up available labor. So the economy is not exactly on the razor’s edge.

And I have some sympathy for Rand Paul’s argument that experimenting with the economy is dangerous. The argument not to raise rates, it seems to me, rests on a ‘this time is different’ argument,. that historically normal business cycles have ended and the world has changed. Maybe it has, but I am always leery of suggesting gravity no longer works.

In any event, I think changing oil balances will offset any interest rate tightening in terms of exchange rates, so I would stay with a 25 basis point increase, but I’ll concede it’s based on mood affiliation rather than hard data.

Menzie wrote:

“How much more appreciation should we expect should the Fed tighten?

“This is actually a harder question to answer than one would think. That’s because over the past seven years, the correlation between the US short term interest rate and the dollar has essentially disappeared as the zero lower bound has placed a floor on rates.”

If a correlation disappears was there ever a correlation or was it simply a special situation given the circumstances and environment? This is one of the problems with demand theory analysis, the assumption of correlation based on unique circumstances rather than sound economic reasoning.

Interesting WSJ article which notes that advanced-economy central banks have been unable to sustain interest rate increases since 2008:

WSJ: Lesson for Fed: Higher Interest Rates Haven’t Been Sticking

Advanced-economy central banks that raised rates recently have all had to backtrack and start cutting

http://www.wsj.com/articles/lesson-for-fed-higher-interest-rates-havent-been-sticking-1442167699

Until you abandon the error of thinking that ‘interest rates are the price(s) of money’, you’re just going to be mired in intellectual confusion. Monetary policy CANNOT be conducted through ‘setting’ an interest rate. Not successfully anyway.