In a globalized American economy, are domestic determinants (e.g., US output gap) the only important factors?

There’s been a lot of talk about how inflation or interest rates will spike due to a collision of fiscal and consumption driven aggregate demand and diminished potential GDP (perhaps due to scarring, supply chain constraints). I wonder if we are missing part of the issue by using a primarily closed economy model.

I remember 40 years ago, my macro teacher (James Duesenberry) remarking on the imminent collision of fiscal and monetary policy leading to crowding out of domestic investment. Because of the (largely unnoted) internationalization of both goods markets and the liberalization of cross border financial flows, we got instead (massive) crowding out of net exports.

With that in mind, I consider this 2019 BIS paper by Kristin Forbes:

The relationship central to most inflation models, between slack and inflation, seems to have weakened. Do we need a new framework? This paper uses three very different approaches – principal components, a Phillips curve model, and trend-cycle decomposition – to show that inflation models should more explicitly and comprehensively control for changes in the global economy and allow for key parameters to adjust over time. Global factors, such as global commodity prices, global slack, exchange rates, and producer price competition can all significantly affect inflation, even after controlling for the standard domestic variables. The role of these global factors has changed over the last decade, especially the relationship between global slack, commodity prices, and producer price dispersion with CPI inflation and the cyclical component of inflation. The role of different global and domestic factors varies across countries, but as the world has become more integrated through trade and supply chains, global factors should no longer play an ancillary role in models of inflation dynamics.

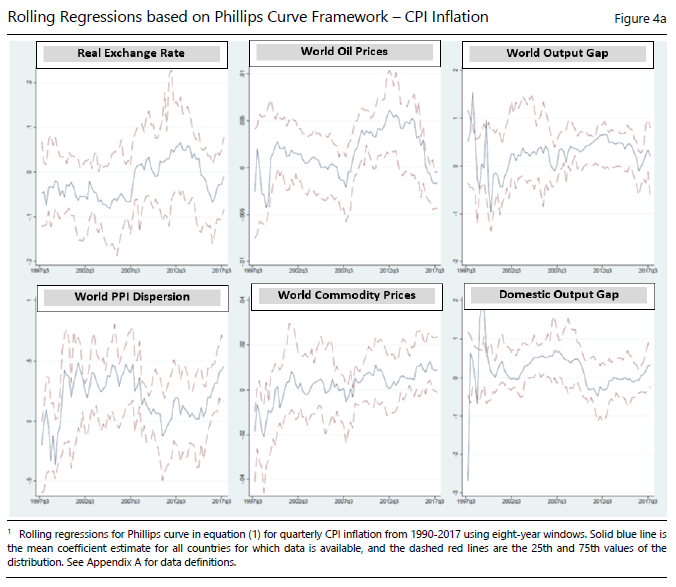

Using rolling regressions on a panel time series sample of OECD countries, Forbes finds in the latter half of the period an increased role the world output gap, and a smaller role for the domestic gap (for CPI headline inflation).

Source: Forbes (2019).

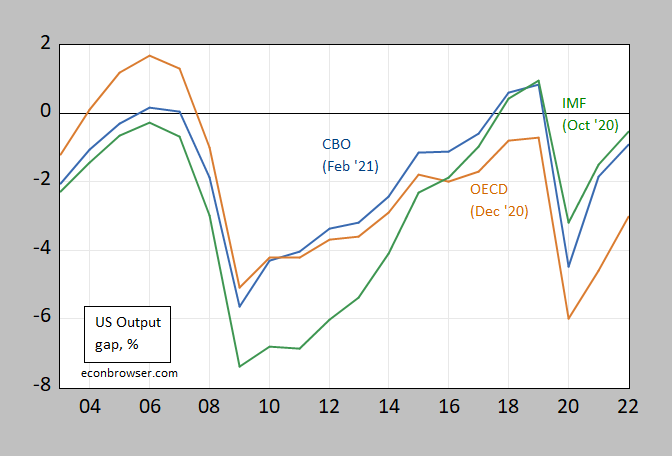

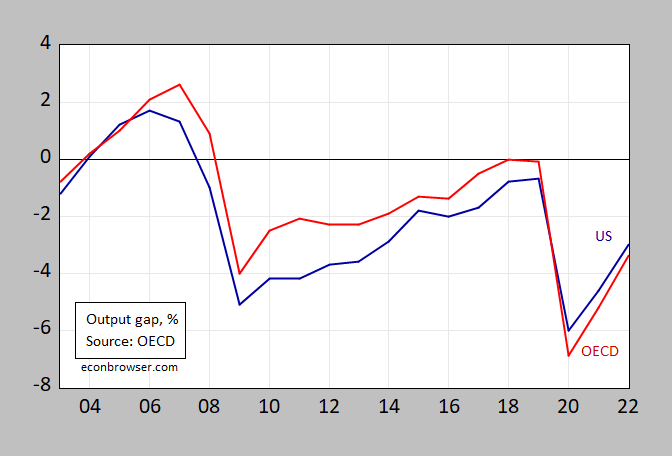

With these results in mind, consider two items: (1) uncertainty regarding the size of the output gap (CBO says it’ll approach zero pretty rapidly, OECD says it’ll be large in absolute value, and persistent), and (2) the sizable OECD-wide output gap.

Figure 1: Output gap, % from CBO (February), IMF (October), and OECD (December). Source: CBO (February 2021), IMF World Economic Outlook database (October 2020), OECD Economic Outlook (December 2020).

Figure 2: US output gap, (blue), OECD (red), in % from OECD. Source: OECD Economic Outlook (December 2020).

Earlier discussion of globalization and inflation, in June 2007, March 2007 , May 2006 . On domestic output gap, see this post.

The world output gap. I wonder what the monetarist will say? Oh yea – let’s construct a measure of the world money supply!

I ask for three things:

1. Assume the US economy is performing under its potential in Q-1 2021, but clearly moving toward that potential;

2. Recognize that just about everybody has been dead wrong about how long and how severe the economic impact of COVID-19 (et al) would be; and

3. Acknowledge that monetary and fiscal policy performance records vs. inflation are far better than vs. deflation.

If those are valid observations, then why in the world is there so much excitement about the possibility of over-shooting, of over-heating the economy?

Let’s over-shoot, because it’s better than the alternative, and if we start to get too much inflation, we know exactly how to deal with it.

The actual fear is not for the country or its economy – its rich people being fearful of making less (or outright losing some of their money), if we get inflation. You are absolutely right there never was nor should there be any real fear of excessive inflation. As Volker proved, you can snuff inflation out quickly at the cost of a short (but nasty) recession. However, I have not seen anybody ever deploy an effective tool against deflation – when the Fed is out of bullets, its out of bullets.

Historically the rich have tended to be able to deal better with inflation than the poor, having access to owning assets that can outrace inflation such as real estate.

‘I remember 40 years ago, my macro teacher (James Duesenberry) remarking on the imminent collision of fiscal and monetary policy leading to crowding out of domestic investment. Because of the (largely unnoted) internationalization of both goods markets and the liberalization of cross border financial flows, we got instead (massive) crowding out of net exports.’

The imminent collision of fiscal and monetary policy was of course Reagan’s defense spending buildup / massive tax cut for the rich and the how Volcker decided to offset it with tight monetary policy. Real interest rates did rise crowding out investment to a degree but the big effect was the massive $ appreciation and crowding out of net exports.

We got a large output gap and a rather quick decline in inflation in large part because import prices fell. Economists like Willem Buiter and Paul Krugman kept warning that when the dollar eventually devalues, the gains in inflation reduction might be reversed. Now this reversal was never obvious but note we had to maintain a significant output gap for a few more years just to keep inflation moderate.

Between 1960 and 1970 when most of the current economic models originated, the U.S. had a surplus every year in its trade balance for goods and services. But in 1980, the trade balance began to shift sharply to deficits and by 2000, the trade deficits began to explode and that trend has continued for the past 20 years.

https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/statistics/historical/gands.pdf

Clearly, the mythical output gap must include our trading partners who apparently have massive spare capacity. It is simply absurd to look at the U.S. economy as a closed model subject to only domestic production limits. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BOPGSTB#0

The data are simply overwhelming the old models. Our low inflation over the past three decades corroborates this proposition. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=gJ4#0

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=nUl9

January 15, 2018

Net Exports of goods and services as a share of Gross Domestic Product, 1948-2020

“But in 1980, the trade balance began to shift sharply to deficits and by 2000, the trade deficits began to explode and that trend has continued for the past 20 years.”

You have been challenged. Your Census Data is in nominal years over several years so nominal growth is not the same thing as the series relative to GDP (inflation as well as growth in real income).

In a globalized American economy, are domestic determinants (e.g., US output gap) the only important factors?

[ The answer for me rests on whether we are willing to be a globalized economy in the manner we were in the wake of the Marshall Plan, when we worked on the development of Europe and Europe in turn lifted our domestic supply constraints. Trade in which we are willing to contribute to development in a country such as Mexico, I would argue, would ease American supply constraints rather than substitute for American domestic production. The last administration viewed trade as necessarily exploiting, and so largely self-defeating. Along with Branko Milanovic, I would envision a Marshall Plan or Belt and Road manner of trade generation as increasing growth potential domestically. ]

ltr: This point is incomprehensible. Capital accounts were largely closed for decades after the Marshall Plan. Tariffs were quite high until the Kennedy round.

Through the Marshall Plan the United States supported economic recovery and capacity building in Europe and this meant increased trade in productive goods. This increasing trade in productive goods, such as machine tools from Germany, allowed for relatively faster US growth. Marshall Plan sort of spending built European production capacity and a production base that the US drew on.

Forgive me, but I am not sure why this assertion is incomprehensible and faulty. Not to presume, but I heard what seemed to be this argument from Branko Milanovic. Milanovic directly and favorably compared the Marshall Plan to the Belt and Road Initiative.

There was a trade conflict not long ago involving the exports of used clothing to countries in eastern Africa. African countries wanted to stop the used clothing imports to allow for building clothing production in Africa. The former US administration used threats to prevent the African ban. What the US could have done however is allow for US investment in Africa that would contribute to building clothing production which in turn could be partially exported.

Forgive me if I am still being incomprehensible and wrong, but I do not know what is wrong with my argument.

ltr: Well, because the Marshall Plan legislation was passed 1948, and globalization is typically thought of as a 1990s onward phenomenon (maybe 1980s), so “in the wake” seems a strange way to discuss the episode. Sure, 40 years after something happens is “in the wake” technically, but not in common usage in the way I was taught.

The loan component of the Marshall Plan was about 10%. My impression is that BRI has a larger loan component. You can correct me if I am wrong.

Marshall Plan legislation was passed 1948, and globalization is typically thought of as a 1990s onward phenomenon (maybe 1980s), so “in the wake” seems a strange way to discuss the episode.

— Menzie Chinn

[ Since I drew on no data only notes on and an impression of a discussion of the Marshall Plan, I was evidently wrong. The impression I had was of an important trade effect for the United States “in the wake” of the Marshall Plan. I was wrong then and surely appreciate the correction.

As for a rough loan component estimate for the BRI, I will look to find or figure that out. But a number far above 10%, as the Marshall Plan component, seems certain.

Really helpful. ]

Paul Krugman argued that NAFTA, while important for employment in Mexico, limited Mexican growth and the benefits we could have gained from Mexican trade in relatively more sophisticated goods. From NAFTA on, Mexico has grown remarkably slowly and with Krugman I find this troubling:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=yRv7

August 4, 2014

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product for Mexico as a percent of Real per capita Gross Domestic Product for United States & Exports of Goods and Services by Mexico as a percent of Gross Domestic Product, 1992-2019

(Indexed to 1992)

The nice thing about Forbes’s work is that she approaches the data in a variety of ways, an attempt to avoid model specification problems.

Her work has gotten lots of attention, which it deserves. For hose disinclined to read her paper, just pop her name into a browser and you’ll find summaries.

Menzie, just checking – Figure 1 is global gaps, Figure 2 is U.S. gaps?

If so, then the implication is for a disinflationary impulse from abroad, no matter the source of the estimate, some dispute over domestic conditions. If the OECD is right, inflation won’t be a problem in the medium term. (Summers misfires again.) If the CBO is right, quantifying the twin effects becomes important. It may be that the U.S. can operate with no slack and no inflation overshoot (Summers misfires, but in a less embarrassing way.) Or we may need to call on the Fed to do it’s job.

So… shouldn’t we be cheering for Summers to be right? Wouldn’t a period of inflation strengthen Fed tools, so that future recessions can be less protracted? Maybe we should leave off hand wringing over inflation until somebody asks Powell whether he has the tools to control inflation.

macroduck: Yes, figure 1 is US output gap estimates from various sources, figure 2 is US and OECD output gaps as estimated by OECD.

I would think that some mild inflation might be good for the economy for a number of reasons. We sure do not seem to have much yet.

So its goodby triangle model, hello polygon model? Interesting that the domestic output gap actually appears negative for a while in the 2000s, if I am reading the axes right. I skimmed the paper and it hybridizes expectations: forward inflation forecasts a la New Keynesian Phillips Curves and lagged inflation. I wonder if we should consider the forward term as a kind of anchoring? If so, the result in the paper that this has become more important has a lot of significance for the debate about inflation and covid relief–anchoring reduces the sacrifice ratio. Thoughts?

Just curious, is the rumor true that Duesenberry is the source of the quip that the life cycle model makes describes perfectly the consumption decision of a tenured professor?

Tom,

I never heard that, and as he is the main father of the relative income/consumption hypothesis, which I think there is a lot to, that would suggest that he thought tenured professors behave differently from most people as the life cycle and relative income theories are usually viewed as being competitors.

Are you participating in the Easterns this year? I am not, although I usually do, in fact, think I saw you at last year’s in Boston, although maybe it was the year before in New York.

This is now seriously off-topic, Tom, but I have heard that this year’s Godleyy lecture at the Easterns by Marc Lavoie suffered some major technical snafu, so has not been available to participants. But as noted, I did not participate this year.

No global gaps? Then my Summers-based points are not operative.

From page 17 of the paper: Why has the common, global component of CPI inflation increased sharply since the 1990s?

Appendix A lists seven components used in the principal components analysis. Surprisingly they did not include what strikes me as the most obvious component; viz., central bank policy inflation targets. I don’t think we should be surprised if differences in central bank targets also explain a lot of the variation in CPI but not necessarily PPI or wage growth.

Mr Mathis,

The US national account goods and services balance averaged 1.8%% of GDP in the 1980s (maxing out at 3.1% after the Plaza Accord), 1.3% of GDP in the 1990s (to 3% in the final quarter), 4.4% of GDP in the 2000s (peaking at 5.9% in late 2005), and 3.1% in the 2010s (maximum 3.8%, early 2011). Since 2017, it has been very steady in the 2.8-3.1% range, which doesn’t sound like a continuation of the 2000s.

Well yea a 3% trade deficit/GDP is not the nearly 6% figure it was at the height of the housing boom and Iraq War. Back then national savings/GDP was quite low. Of course as we recover the current housing market combined with fiscal stimulus may crowd out net exports – much like Menzie was noting occurred in the early 1980’s.

Republican Senator Josh Hawley is rumored to be working with Bernie Sanders on some new idea to make large companies raise wages. I wonder how irked Mitch McConnell is with Hawley now!

Kevin Drum notes two related things. One is that we are not importing that much in Saudi oil any more:

https://jabberwocking.com/heres-what-happens-when-we-no-longer-need-saudi-arabian-oil/

Secondly not have to rely on the Saudis may be one reason our new President is standing up to this regime!

We have never imported all that much, with Canada, Mexico, and Venezuela our more important sources. Focusing on who is sending oil to whom is basically misleading because oil is so fungible. What really matters is global supply and demands, so Saudi threats to either cut production (or more specifically exports as in 1973) or to increase it are what matter, with that effect working through the global prices. So in this Drum piece he has the Saudis threatening to increase production to hurt the US oil industry, which given that US is now a net exporter by a narrow margin may be the more serious potential source of pain.

In 1973 the Saudi oil export embargo did not hurt the US because, oh dear, we could not get Saudi oil. It hurt us, a major importing nation, because the price of oil tripled or quadrupled. It was the oil price shock that hurt the US economy.

As it is, oil prices have risen quite a bit recently, and it is clear the Saudis like that, and they have helped goose that by cutting production, with Brent now around $67 per barrel, while it was barely above 440 a year ago or so. There is talk they may increase production again, but that is not to hurt the US producers but to make more money for themselves with those higher prices they have now managed to achieve;.

“We have never imported all that much, with Canada, Mexico, and Venezuela our more important sources. Focusing on who is sending oil to whom is basically misleading because oil is so fungible.”

Granted. I went back to Kevin’s graph which had no perspective. I next went to Census. We did import $54 billion of oil from the Saudis back in 2012 but our total oil imports were exceeding $300 billion per year.

BTW, that the price of oil has been rising for some time is one reason why we may be seeing more inflationary pressure from the globalized economy, with this possibly becoming significant if those prices keep rising. I note that just today I saw on the blog Oil Prices Today a report that various bankers are now forecasting that oil may reach $100 per barrel. I do not know if that will happen, and if KSA increases production (and I read oil rigs are increasing in the US) the price may well stall out before it gets there. But if it does or gets close that will certainly add to inflationary pressure.

$100 a barrel? Now if oil prices did go to that level, that would be rather harsh although we saw higher prices over the 2011-2014 period. Right now WTI just past $60 a barrel where it was back in December 2019:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DCOILWTICO

Brent continues to have a premium of several dollars over WTI. Several months ago that got down to only about a dollar a barrel, but has more recently opened up again. There used to be almost no difference between them, but for several years now these markets have been substantially disconnected, although their movements do correlate.

We have had higher oil prices in the last decade without much inflationary pressure, but that did not reflect an increase after a substantial period of much lower. I continue to side with Jim Bullard at the Fed that we are likely to see some near term increase in inflation, with supply chain problems playing a role. Of course oil as an inflationary pressure has always come from the suplly/cost push side.

The Brent-WTI is around $3 a barrel. Is that a significant premium in light of what was happening about a decade ago. But one must pay tribute to the 3 Econbrowser posts on this topic by James Hamilton when noting this spread here:

https://econbrowser.com/archives/2013/07/brentwti_spread_2

I was curious so I used FRED to plot Brent, WTI, and their spread over the 2015 to 2019 period as sort of an update to Dr. Hamilton’s excellent posts. I stopped with Dec. 2019 as we know prices went a bit wacky after the pandemic. I was surprised that the average Brent price ($57.19) was $4.26 higher than the average WTI price ($52.93). The spread fluctuated between near zero to around $10 at one point in 2018. Why this rather higher but volatile spread has existed would be an interesting post if any has an explanation.

pgl,

Jim’s comments as usual on this topic were highly reasonable. I do not know why we are seeing the more recent changes that have been occurring, although the current gap is not all that unusual relative to averages over some period of time.

I will confess to being unaware of the Forbes paper – of course, my available time for reading has declined quite a bit in the last decade, too. Anyway, my first thought on looking at her study was “Wow.” My first (quick) impressions are that 1) she’s brave to attempt to disentangle all the various effects, and 2) she’s done some very good and very useful work here. This is a paper that I need to spend more time with. It almost makes me wish I was still teaching this stuff.