According to official data published by the National Bureau of Statistics, China’s growth q/q seasonally adjusted slowed considerably in Q3, to 0.2% (not annualized), below the Bloomberg consensus of 0.5%. The four quarter growth rate was 4.9%, vs consensus of 5.2%.

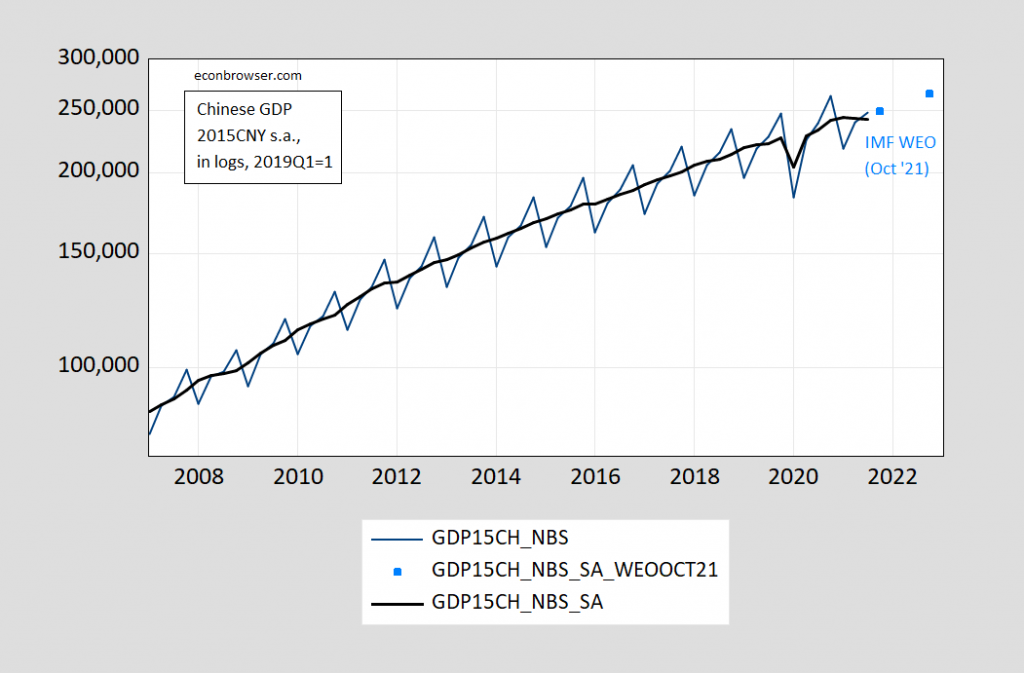

Figure 1 depicts real GDP over the period NBS reports it:

Figure 1: Chinese real GDP, in 100 mn 2015 CNY (blue), seasonally adjusted using Census X-12/X-11 seasonal filter (black), and IMF WEO forecasts applied to seasonally adjusted series (sky blue squares), on log scale. GDP in constant 2015CNY calculated by author by using IMF WEO GDP price deflator to convert implicit deflators to a common base year. Source: China National Bureau of Statistics, IMF October 2021 WEO, and author’s calculations.

Using the seasonally adjusted, and applying the IMF’s forecasts to these seasonally adjusted numbers, it’s clear how much the Q3 figure was a miss given expectations.

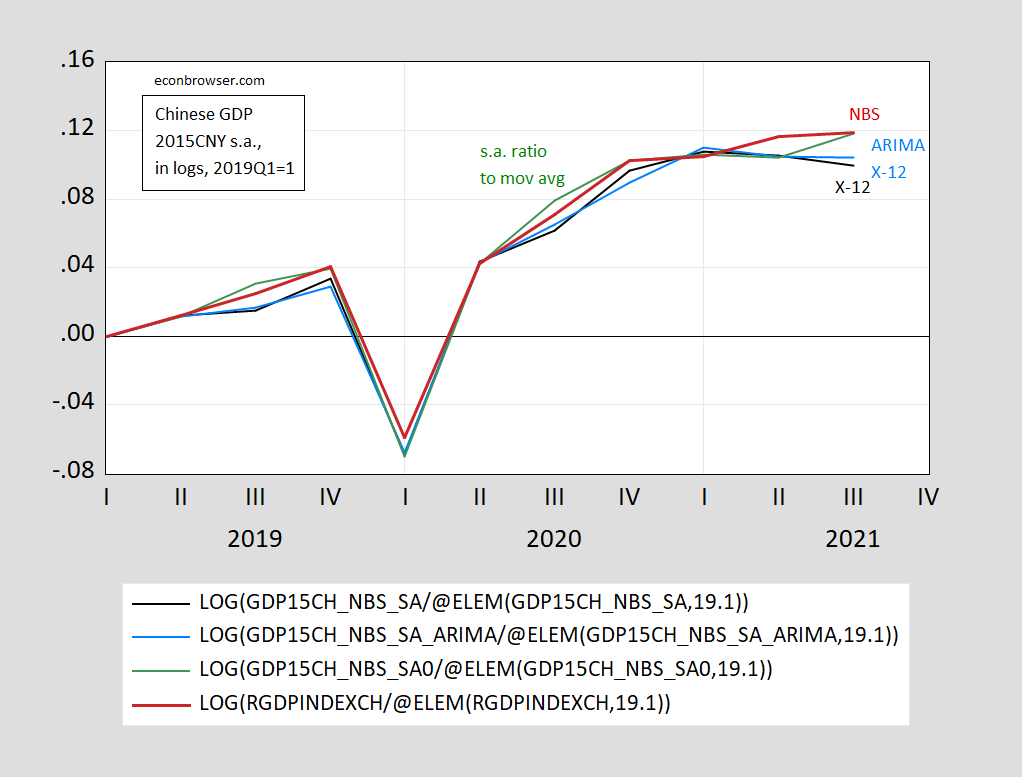

In my mind, it’s a bit mysterious how the NBS q/q growth numbers were obtained. On the NBS website, seasonally unadjusted nominal GDP numbers are reported, as are seasonally unadjusted real numbers in different constant yuan, and seasonally adjusted q/q real growth rates (from 2011 onward). That means it is not straightforward to replicate the implied Chinese seasonally adjusted GDP level, since they use an in-house seasonal adjustment methodology (NBS-SA, see here). I apply several seasonal adjustment procedures, including a geometric ratio to a moving average, Census X-12/seasonal filter X-11, and ARIMA Census X-12/seasonal filter X-11, and compare against the implied GDP series obtained by cumulating NBS reported q/q changes.

Figure 2: Chinese real GDP estimated using Census X-12/seasonal X-11 (black), ARIMA Census X-12/seasonal X-11 (sky blue), ratio to moving average (green), and implied by NBS reported q/q growth rates (red), all in logs, normalized to 2019Q1. Source: NBS, and author’s calculations.

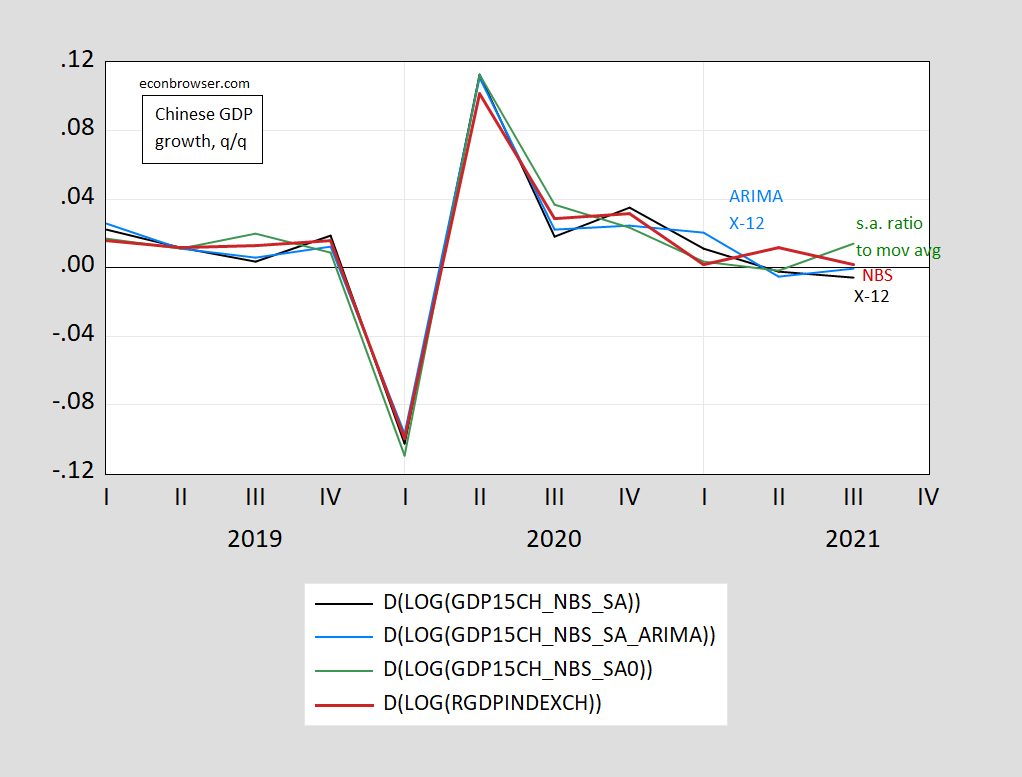

Notice that the official series indicates continued growth albeit slow, while two of three standard seasonal adjustment procedures show negative growth. This can be seen in the graph of growth rates (calculated as log-differences):

Figure 3: Quarter-on-quarter growth rates of Chinese real GDP estimated using Census X-12/seasonal X-11 (black), ARIMA Census X-12/seasonal X-11 (sky blue), ratio to moving average (green), and NBS reported q/q growth rates (red), all calculated as log-differences. Source: NBS, and author’s calculations.

Over the last two quarters, cumulative growth estimated using X-12 adjusted GDP has lagged NBS reported growth, raising the question whether the numbers have been massaged. Some people would respond that it’s a foregone conclusion that they were. However, as noted in this post, Chinese measures of economic activity are not obviously over- or understating actual activity, particularly in recent years. Fernald, Hsu and Spiegel (2020) [working paper version] construct a “China Cyclical Activity Tracker” (C-CAT) [see letter], and conclude:

We choose a preferred index of eight non-GDP indicators based on their fit to Chinese imports, which we call the China Cyclical Activity Tracker (or C-CAT). We find that Chinese statistics have broadly become more reliable in measuring cyclical fluctuations over time. However, measured GDP has been excessively smooth since 2013, and adds little information relative to combinations of other indicators.

The authors have done a preliminary check on the 2021Q3 GDP, using a new, unpublished quarterly version of their C-CAT (the original published version is on a 4 quarter basis). They note that using Haver data — which does not match NBS data –, reported GDP is 31 basis points (bps) below trend in standard deviation units, while their preliminary reading indicates 119 bps below trend for a preliminary reading of q-on-q estimates of the China CAT and 170 bps below trend for q-on-q estimates of a quarterly version of their “All indicators” index (both without consumer expectations, which have yet to come in for the quarter). Those preliminary results confirm the reported results in showing a slowdown for Q3, but look even a little weaker than even what non-NBS GDP series report. (Thanks to Fernald and Spiegel for their results).

(Haver’s series indicates -2.26% q/q growth SAAR, well below NBS’s -0.8%, and closer to my X-12 series (black line) above, -2.3%).

Journalistic accounts (e.g., NYT) have attributed the Q3 slowdown to the financial fallout from the Evergrande default as well as more general real estate troubles, slowed auto production due to chip shortages, and power outages/shortages.

The deceleration is important for the obvious reason that Chinese GDP now (2021) accounts for a larger share of world GDP than it did back in 2008: 17.8% vs. 7.2%; the 2021 share for the US is 24.2% (all shares calculated using GDP in US dollars at market exchange rates as reported in the IMF’s WEO database).

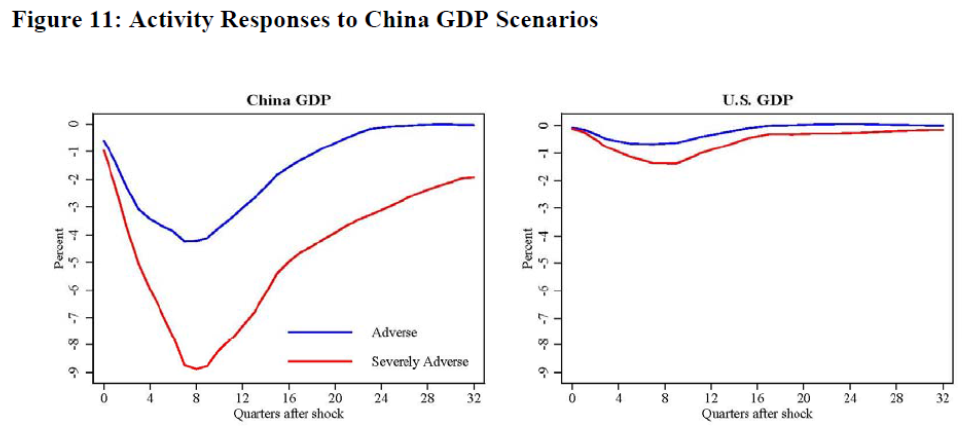

What’s the spillover effect? Ahmed et al. (2019) examine implications of a China slowdown (discussed in this post).

…the VAR estimates also suggest that the hit to economic activity in different countries and regions would generally be significant (consistent with China’s strong trade links with other economies). More specifically, the output hit to EME commodity exporters would be about ¾ as large as the hit to China itself; to other EMEs would be about half; to advanced economies excluding the United States slightly more than a third; and only a relatively modest hit to the United States. The smaller U.S. effect reflects the U.S. economy being more closed, limited direct U.S. financial linkages to China, and greater capacity at the moment (than other advanced economies, say) to ease monetary policy to cushion the blow.

The impact of a 4% shock (blue), estimated using a SVAR, is shown below:

Source: Ahmed et al. (2019).

Of course, the relationships that obtained pre-pandemic are unlikely to hold fully in the current environment, but the implications are straightforward. The impact also depends on the persistence of the shock; the more long-lived the measures implemented by the Xi regime, the less likely the resumption of rapid growth (at least in the short term). In a recent op-ed, Arthur Kroeber lays out the macro challenges facing China in the context of Xi’s objectives, and hence the motivation for these regulatory measures.

My understanding (correct me if this is way off) is that China exports $2500 billion per year and imports about $2250 billion per year. Of the latter – Census is saying the US exports only $125 billion per year to China. So which other nations have been exporting a lot to China? I know Australia does so it would be seriously affected by a slow down in Chinese economic growth.

From Figure 2 it is a simple matter to deduce the NBS method of calculating GDP.

1) Reflect published input data when doing so doesn’t conflict with 2).

2) Never report a decline in GDP.

3) When 2) requires dishonesty, try to regain credibility by matching NBS GDP estimates to the highest other GDP estimates in subsequent quarters.

The Evergrande episode highlights the very high level of malinvestment in residential property in China. Even if some other driver of growth can take over for residential investment (recently at least 29% of output), there has to be a period in which resources a redirected to other sectors. China will spend some quarters away from the old production possibilities frontier. Reduced productivity, stranded assets, unemployment, retraining, financial and demand shocks. ltr is going to have soooooo much to paper over and deny.

None of this bodes well for China’s trading partners (Figure 11), but it also bodes ill for Taiwan, India, Australia, the U.S., Tibet and any other country which can serve as a distraction from China’s internal problems. North Korea can stir up distractions with China’s encouragement, too.

Kinda think any country intending to amortize Belt-and-Road borrowing through trade with China is in for a disappointment, too.

China’s century is going to be a hoot.

Aside from just possibly erratic behavior by Beijing bureaucrats to start a war, this is why all the “Century of China” bloviating by media folks wanting web hits doesn’t phase me in the least. I lived there long enough to know how exceedingly dysfunctional their society is. I can give just a single isolated example of what I could easy give you a laundry list of. I taught mostly university age students. But the emotional/social maturity of those students, was….. I don’t want to say “stunted”, but I would say “behind” USA university students by roughly 4 years. Now, about 85% (guesstimating) of my students were females. And male students in China are even more immature than the females (keep in mind this is coming from someone other commenters on this blog have labeled “sexist”). So then for the male university students you might say 6 years behind in social/emotional maturity. Again, aside from erratic behavior from government officials towards foreign nations, this disfunction and immaturity doesn’t exactly insert fear in your heart. Here is a group of people (I’m discussing mainland Chinese, who loves to brag they have superior math skills to most Americans (I would say, as a white male American, most Chinese do exhibit superior skills in math) but at the same time, refuse to publish accurate economic statistics. Now, the gentle reader may label that whatever word they like. I’m going with dysfunctional.

I’ve mentioned this idea before, but it just nags at me – China may be arriving at the peak of its international power: https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/10/18/china-danger-military-missile-taiwan/

If past performance were a guarantee of future returns, China’s outlook wouldn’t be in much doubt. That’s not the way things work.

Output per labor hour is still quite low in China: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/labor-productivity-per-hour-pennworldtable?tab=map

If all were well, we could expect China to narrow the productivity gap over time, thereby increasing its power in the world. But all isn’t well. China requires a extraordinary amount of new debt per unit of output at the same time that trend growth is slowing. That implies a gargantuan increase in debt on the way to becoming as well off as Mexico or Equitorial Guinea or Russia.

Part of the problem is that a lot of credit is (had been?) going to residential construction, which doesn’t increase productivity. And much of that construction is for second and third residences, part of a saving scheme for households facing a loss of value on bank deposits due to financial repression. There is neither productivity nor welfare gain from constructing homes which stand empty.

The progression from command economy to directed credit and heavy-handedness has worked for China in the past, but that approach is showing – what do ya call ’em? – internal contractions. Maybe China is better off without Jack Ma, but it is hard to imagine something other than a fairly pure price mechanism handling the complexity of a modern economy.

Making economic statisticians lie about growth (see Menzie’s post)is a symptom of serious problem. If underlings cannot tell bosses the truth, what hope is there that bosses will make even halfway decent decisions?

If we are watching China stepping down to a much lower pace of trend growth, global growth is also in the process of stepping down.

I think China has a lot of room for improvement in economic productivity. They have a lot of untapped/unused human capital. If and when they decide that’s more important than the communist part hierarchy, is the same day, or the start of the unstoppable climb, of harnessing their true power. Again, this gets back to many things including the fact they don’t want a strong RMB because to have a strong RMB on international markets the communist party must forfeit power over its domestic populace and forfeit capital controls. None of which will happen in the next 20–40 years. And neither will Kopit’s laughable prediction of a proletariate rebellion.

Moses,

You’ve heard of the “middle-income trap”. This piece takes a look (as have many others) and find some risk factors for falling into the trap:

Convergence success and

the middle-income trap

Jong-Wha Lee

Abstract

This paper investigates the economic growth experiences of middle-income economies over the

period 1960-2014 focusing on two groups of countries. The “convergence success” group includes

middle-income economies which graduated to a high-income status or have achieved rapid

convergence progress. When an economy in the “non-success” group experienced growth

deceleration and failed to advance to a high-income status, we defined such episodes as the

“middle-income trap”. We observe no clear pattern that the relative frequency of growth deceleration

was higher for upper-middle-income economies, thereby refuting the “middle-income trap

hypothesis”. The probit regressions show that “convergence successes” tend to maintain strong

human capital, a large working-age population ratio, effective rule of law, low prices of investment

goods, and high levels of high-tech exports and patents. Adding to unfavourable demographic, trade

and technological factors, rapid investment expansion, hasty deregulation and hurried financial opening could cause the “non-successes” to fall into the middle-income trap.

It is not entirely up to Chinese officials whether China falls into the trap, but partly. Demographics don’t favor China. Nor, perhaps, does the rule of law. Investment? Malinvestment is rampant.

http://www.news.cn/english/2021-10/18/c_1310252462.htm

October 18, 2021

China’s GDP expands 9.8 pct in first three quarters

BEIJING — China’s economy continued stable recovery in the first three quarters of this year with major indicators staying within a reasonable range, official data showed Monday.

The country’s gross domestic product (GDP) expanded 9.8 percent year on year in the first three quarters, putting the average growth for the period in the past two years at 5.2 percent, data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) showed.

In the third quarter (Q3), the country’s GDP grew 4.9 percent year on year, slower than the growth of 18.3 percent in Q1 and 7.9 percent in Q2.

“The Chinese economy has maintained the recovery momentum in the first three quarters with progress in structural adjustment and high quality development,” said NBS spokesperson Fu Linghui.

Consumption contributed the lion’s share to the economic growth in Jan.-Sept., while net exports contributed 19.5 percent to the GDP increase.

Major economic indicators showed continued improvements across the board, with retail sales of consumer goods jumping 16.4 percent year on year in the first three quarters this year.

China’s value-added industrial output went up 11.8 percent year on year in the first three quarters, while fixed-asset investment went up 7.3 percent year on year during the period. *

The country’s surveyed urban unemployment rate stood at 4.9 percent in September, 0.5 percentage points lower than the same period last year, NBS data showed.

During the Jan.-Sept. period, China added 10.45 million new urban jobs in the first three quarters, achieving 95 percent of the target for the whole year.

Recognizing the progress, Fu cautioned against rising uncertainties in the international environment and uneven recovery in the domestic economy, adding that the country will take various measures to keep the economy running within a reasonable range.

* http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2021-07/15/c_1310062512.htm

Fixed-asset investment includes capital spent on infrastructure, property, machinery and other physical assets.

http://www.news.cn/english/2021-10/21/c_1310260571.htm

October 21, 2021

World’s “most resilient” economy leverages financial tools for better development

— China’s super-large economy boasts strong resilience and the country can achieve its full-year economic target with this resilience underpinning its development.

— In tackling COVID-19, China has prioritized the task of maintaining the vitality of the real economy.

— To meet the country’s carbon peaking and neutrality goals, China’s financial policymakers have placed the transition to a low-carbon economy high on the agenda, despite COVID-induced growth challenges.

— While steering more funds to the real economy and green development, China has also kept a cautious eye on lurking financing risks at home and abroad, stepping up supervision and striving to stabilize development.

BEIJING — While major economies are pondering when to withdraw their ultra-loose monetary policies, China’s policymakers have a different issue in mind: how to better leverage financial tools to restructure the economy and secure high-quality development.

At the ongoing 2021 Annual Conference of Financial Street Forum, China’s policymakers have shrugged off concern over the country’s slower economic growth in the third quarter, with full confidence about where the Chinese economy is heading.

China’s super-large economy boasts strong resilience and the country can achieve its full-year economic target with this resilience underpinning its development, said Chinese Vice Premier Liu He when addressing the opening ceremony of the forum Wednesday.

In the opinion of Central Bank Governor Yi Gang, China’s economic system is “the most resilient one in the world,” as the country has successfully coped with the ravage of COVID-19, becoming the first economy to grow last year and logging 9.8 percent growth in the first three quarters compared with the year’s target of over six percent.

Combing through speeches delivered by policymakers at the forum, one might find that the real economy, green transition, and risk control are among China’s financial policy priorities to boost economic recovery and secure more sustainability.

FUELING THE REAL ECONOMY

When the economy is battered by external shocks, market entities often face severe competition or even live-or-die tests. That’s when the financial sector helps secure financing for those in need, Yi said.

In tackling COVID-19, China has prioritized the task of maintaining the vitality of the real economy. Last year, China’s central bank rolled out three monetary and credit policy packages totaling 1.8 trillion yuan (about 281.7 billion U.S. dollars) targeting micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises, followed by another 300-billion-yuan re-lending fund this year.

These monetary and credit measures, along with fiscal policies, have directly supported millions of market entities. So far, over 40 million entities have benefitted from inclusive small and micro-loans, said the governor.

Vice Premier Liu He stressed that China has adopted a prudent monetary policy that is flexible, precise, and appropriate, with a focus on key areas in its economic structure. Meanwhile, the multi-level capital market system has further improved with the establishment of the Beijing Stock Exchange to increase financing support for innovative small and medium-sized enterprises.

He encouraged the financial sector to take a more proactive approach to better serving the real economy, channeling more funds to small firms, and scaling up science and technological innovation support.

Deeming the manufacturing industry key to deepening supply-side structural reform, China’s lenders have been funneling more funds to the sector. For instance, outstanding loans granted by the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China to the manufacturing sector exceeded 2 trillion yuan in the first half of the year, said Liao Lin, head of the bank.

FINANCING A GREEN FUTURE

To meet the country’s carbon peaking and neutrality goals, China’s financial policymakers have placed the transition to a low-carbon economy high on the agenda, despite COVID-induced growth challenges.

As one of the first countries to develop green finance, China has, over the past five years, picked up pace in establishing a green finance framework….

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=HAKs

August 4, 2014

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product for China, Germany, India, Japan and United States, 1977-2020

(Percent change)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=HAKv

August 4, 2014

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product for China, Germany, India, Japan and United States, 1977-2020

(Indexed to 1977)

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2021/october/weo-report?c=924,134,532,534,536,158,546,922,111,&s=PPPGDP,&sy=2007&ey=2020&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1

October 15, 2021

Gross Domestic Product based on purchasing-power-parity (PPP) valuation * for China, Germany, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Japan, Macao, Russia and United States, 2007-2021

2020

China ( 24,672)

Germany ( 4,537)

India ( 8,975)

Indonesia ( 3,302)

Japan ( 5,312)

Russia ( 4,100)

United States ( 20,894)

* Data are expressed in US dollars adjusted for purchasing power parities (PPPs), which provide a means of comparing spending between countries on a common base. PPPs are the rates of currency conversion that equalise the cost of a given “basket” of goods and services in different countries.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=lwga

January 15, 2018

Real Broad Effective Exchange Rate for China, Germany, India, Japan and United States, 2007-2021

(Indexed to 2007)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=gxkQ

January 15, 2018

Real Broad Effective Exchange Rate for China, Germany, India, Japan and United States, 1994-2021

(Indexed to 1994)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=ERCg

January 30, 2018

Consumer Prices for China, Germany, India, Japan and United States, 2007-2021

(Percent change)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=mGFp

January 30, 2018

Total Reserves excluding Gold for China, Germany, India, Japan and United States, 2007-2021

This is all noise, right? GDP is purely political, no?

rsm: See the paper linked in the post.

Paypuh?!?!?!?! We don’t need no stinkin’ Paypuuuh!!!!!!!!

“Noise” and “political” cannot both be true. Noise is random, political manipulation is not. Maybe you could pick a form of dismissal instead of just sprinkling without thought?

You have a pattern of dismissing economic data without understanding why you might or might not want to take those data seriously. Kind of “a pox on numbers” attitude. I’m sure that saves time, but spending time on stuff before dismissing wouldn’t hurt you. You might learnsome economics.

The disjuncture here between the fairly pessimistic estimates about China’s growth made by the various people Menzie cites and the pollyannaish reports ltr cites that have the effect of the Evergrande difficulties and the accompanying slowdown of real estate investment amounting to very little in terms of impacts on China’s growth is much larger than I am used to seeing in terms of estimates regarding the situation in China. I do not see how one easily reconciles this apparently large gap, suspecting reality may be somewhere the extremes here, but I am not in a position to determine which that reality is actually closer to.

However, if the more pessimistic outlook presented here by Menzie proves to be more accurate, this would support his earlier post about energy futures markets seeing where prices have gotten to as near a peak, with some decline likely in the not-too distant future as the reduced growth in China kicks in and has its negative multiplier effects on the rest of the world’s economy. But I suspect that at least for this winter people in the US heating with natural gas are still likely to see some substantial escalation of their winter heating bills, even if those prices do subside somewhat later. Some of the price increases we have already seen seem to be still working their way through the pipeline, so to speak.

I have not seem much increase in production from texas shale, even with the high prices. Right now conditions do not seem to support expansion of drilling activity, especially from the smaller producers. My guess is producers are happy keeping oil and gas around the current levels. Very profitable for them. Higher prices from increased demand will force them into expensive expansion and unknown future, something the are happy to avoid for now. Employment conditions may make it hard to increase production quickly.

Last year the view was that US producers get going if price above $70. Why they are not now when it is around $85 is unclear. But more important on supply side is Russia and Saudi Arabia, especially the latter, restraining production.

Of course, if China does slow substantially, that could move the demand side in a way to bring about the futures markets forecasts as reality, as I noted.

i think in texas, producers have concerns they cannot activate a workforce in a timely manner for expansion. this would impact their decision to ramp up. exxon just shut down two office buildings in the woodlands, in order to more consolidate their workforce.

and if you follow the technology front in the oil patch, i see fewer jobs advertisements related to r&d in the oil patch. i used to see a variety of openings focusing on big data and other analytics for reservoir simulation. that seems to have dried up a bit. years ago exxon tried to recruit me to run one of their research labs. last i heard, that lab was now shut down. not sure exactly what technology they are pursing today.

http://www.news.cn/english/2021-10/26/c_1310268260.htm

October 26, 2021

Key insights into China’s current economic situation

BEIJING — As 2021 marks the beginning of China’s 14th Five-Year Plan period (2021-2025), as well as the start of its journey to fully build itself into a modern socialist country, the nation’s economic performance has come under the spotlight.

How is China’s economy doing so far? Are there any new situations emerging, or existing issues left unresolved? With the pandemic and economic trend becoming more complicated, where is the world’s second-largest economy heading?

In response to the significant attention to and concerns over the Chinese economy from both home and abroad, Xinhua has interviewed a number of authoritative departments and individuals, and the following are some of their opinions and judgments on 10 issues of China’s economy.

GROWTH MOMENTUM

China’s GDP grew 4.9 percent year on year in the third quarter, slower than its growth of 18.3 percent in the first quarter and 7.9 percent in the second quarter. In the first three quarters, the country logged a 9.8 percent GDP expansion, well above its annual growth target of over 6 percent, official data shows.

The growth slowdown was the result of challenges including a resurgence of COVID-19 cases and severe flooding in certain regions, as well as a higher comparison basis in the same period last year, according to authorities.

China is fully capable of achieving its social and economic development goals for the whole year, and the sound momentum of economic development for the long-run has remained unchanged, they told Xinhua

DOMESTIC DEMAND

China’s retail sales of consumer goods jumped 16.4 percent year on year in the first three quarters of 2021, slower than the 23 percent seen in the first half. The country’s fixed-asset investment increased 7.3 percent year on year, down from 12.6 percent in the first six months.

Despite the falling growth, China has staying power in domestic demand expansion supported by a super-scale market of over 1.4 billion people, effective policies to boost consumption, and has seen steady progress in the country’s major projects set for the 14th Five-Year Plan period.

In the first three quarters, final consumption contributed 64.8 percent to China’s economic growth, 3.1 percentage points higher than the level seen in the first half, according to official data.

FOREIGN TRADE

China’s foreign trade staged a stellar performance in the first three quarters, with total imports and exports expanding 22.7 percent year on year to 28.33 trillion yuan (about 4.43 trillion U.S. dollars), beating market expectations and playing a bigger part in driving growth.

Considering factors including a high base in the second half of 2020, the country’s foreign trade is likely to grow at a slower pace compared to a year ago, presenting a “high-to-low” curve.

But authorities estimate orders for key foreign trade enterprises will remain sufficient until the second quarter of next year. Imports and exports are therefore expected to sustain steady growth this year.

SUPPLY-SIDE STRUCTURAL REFORM

Since the start of this year, high-quality development has become a more distinctive hallmark of China’s growth, with the country’s economy seeing optimized structures, improved development quality and stronger growth momentum.

Structural reform has been pressing ahead in a sound manner, as manifested in the steady industrial capacity utilization rate, the declining asset-liability ratio of enterprises, and rapidly expanding investment in weak links such as education and healthcare.

Despite the progress achieved, authorities have cautioned that an excessive production capacity may occur, as other countries will gradually reopen their factories at home, leading to a pullback in China’s exports.

Coping with the challenges faced by China’s economic growth requires an unswerving focus on economic restructuring. At a key meeting held in July, China’s policymakers pledged to tighten the power use limit on energy-intensive industries, saying that steps will be taken to refrain from using the property sector as a short-term economic stimulus and to speed up the development of affordable rental housing.

POWER SUPPLY ….

note the web link for this story is from the ccp propaganda arm. not a news outlet.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=IdPM

August 4, 2014

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product for United States, United Kingdom and China, 1977-2020

(Percent change)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=IdPT

August 4, 2014

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product for United States, United Kingdom and China, 1977-2020

(Indexed to 1977)

We should be clear about a few things. First, the expected consensus (5.2%) is based on what those who were polled expected the government to announce. That’s not the same as an expectation that the economy actually grew that amount, just a view on what the government would say the economy did. There’s a difference, and it is nontrivial.

Second, the Bloomberg (et al) alternative GDP figures are wholly based on data supplied by the same official sources used by everyone. No one is gathering their own primary data in these exercises (it’s illegal), they’re just reworking what’s available.

Third, the most frustrated economist you are ever likely to encounter is someone trying to make Chinese statistics add up. They are not internally consistent, and plugging them into any kind of econometric model is an excellent example of GIGO. Trust me on this; I did it for decades.

A short example:

Nominal GDP growth, Q1 2021 +21.2%; Q2 2021 +13.6%; Q3 2021 +9.8%

CPI Inflation Q1 2021 -0.1% %; Q2 2021 +1.3%; Q3 2021 +1.1%

Real GDP growth, Q1 2021 +18.3%; Q2 2021 +7.9%; Q3 2021 +4.9%

Now, we know CPI isn’t the GDP deflator, but seriously …

– – – – –

pgl,

Chinese imports by top five source, percent share

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ 1981-2000 avg p.a. _ _ 2001-2020

Hong Kong _ _ _ 35.4% _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 15.5%

Japan _ _ _ _ _ _ _20.1% _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 10.5%

Taiwan _ _ _ _ _ _ 29.0% _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 8.8%

United States _ _ 11.4% _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 7.5%

Korea _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _1.9% _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 9.7%

Others _ _ _ _ _ _ _2.2% _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _48.1%

There’s a lot of transhipment through Hong Kong, and the Taiwan and Korea numbers have to be considered in light of the fact that trade with China was illegal (treasonous, in the case of Taiwan) for most of the 1980s.

ADB.org: https://kidb.adb.org/economies/china-peoples-republic-of

– – – – –

macroduck,

If past performance were any indicator of future reality, all the past predictions of China’s pending collapse would have made these discussions moot.

Yes, China’s economy will stop growing fast someday, but the odds are that day has yet to come.

Yes, there is a chance that any economy will “collapse,” if we use the term loosely, such as might be applied to Japan after its stock market crash 30 years ago. But, not today.

Bear in mind that (according to the official data) real retail sales are soaring in the first nine months of this year.

Oh, and Q-1 2020 was the only quarter in which China recorded a YoY decline in real GDP.

http://www.news.cn/english/2021-10/26/c_1310268260.htm

October 26, 2021

Key insights into China’s current economic situation

[ Continuing ]

POWER SUPPLY

Since mid-September, power supply across the country has been tight, reflecting the unbalanced supply and demand of energy, especially coal. Power cuts occurred in certain areas from Sept. 23 to 26, causing widespread concern in society.

To cope with the situation, the National Development and Reform Commission said in a series of announcements that it would take necessary measures, including legal intervention in coal prices, to bring the coal market back to rationality and ensure a stable supply of energy.

The National Energy Administration recently announced that it will promote the integration of new energy power generation projects and further improve the power supply capacity.

An improved pricing mechanism for coal-fired power was also released to deepen market-oriented pricing reform in the sector.

GLOBAL INDUSTRIAL, SUPPLY CHAINS

As certain countries act against globalization and the COVID-19 pandemic sweeps across the world, the stability of the global industrial chain and the smooth flow of the global supply chain are confronted with unprecedented challenges.

Thanks to China’s timely containment of COVID-19, the stable operations of industrial and supply chains have been secured, and the layouts of multinational companies have increased.

Statistics show that more than 90 percent of foreign companies in China operate mainly in the Chinese market. With a population of 1.4 billion and over 400 million middle-incomers, China has a consumer market of unparalleled size and growth potential.

In addition, the comprehensive advantages of complete industrial facilities, complete infrastructure and abundant human resources have become magnets for foreign investment.

The double-digit year-on-year growth in foreign direct investment into the Chinese mainland in actual use in the January-September period has also confirmed this trend, highlighting that China remains one of the best investment destinations in the world.

Making industrial and supply chains more autonomous and controllable does not require a closed and inward-looking mindset. Rather, it means opening up to a higher level and strengthening overall competitiveness through opening-up and cooperation.

COMMON PROSPERITY

Since the beginning of the year, China has taken a slew of measures to promote common prosperity. While attracting high attention, the term has been misinterpreted by some as “robbing the rich to help the poor.”

Rather than having just a few prosperous people, common prosperity, which is an essential requirement of socialism, refers to affluence shared by everyone, physically and intellectually.

China has been gradually placing common prosperity in a more prominent position since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2012. Now, having achieved victory in the anti-poverty fight and in the construction of a moderately prosperous society in all respects, the country has favorable conditions to promote common prosperity.

In pursuit of this goal, efforts will be made to properly deal with the relationship between efficiency and fairness, make basic institutional arrangements for income distribution, expand the size of the middle-income group, increase the earnings of low-income groups, adjust excessive incomes, and prohibit illicit incomes to promote social fairness and justice.

ANTI-MONOPOLY

China has unveiled a series of regulatory measures to rein in certain monopolized sectors and the disorderly expansion of capital. These are pragmatic and necessary efforts to promote the sound development of related industries as well as social fairness.

The anti-monopoly measures target illegal acts, rather than the private sector or companies of any specific ownership type.

Thanks to these moves, the flow of capital has seen new trends, with sci-tech innovation, high-tech manufacturing and the industrial internet being new fields that attract capital.

China has been widely recognized as one of the leading nations in the digital economy, meaning it needs more relevant regulations to promote the sound development of related sectors.

RURAL VITALIZATION

After a complete victory in eradicating absolute poverty, China’s focus in work related to agriculture, rural areas and rural residents has shifted to comprehensively promoting rural vitalization.

How to prevent a large-scale return to poverty and deliver the rural vitalization strategy has attracted much attention at home and abroad.

The full implementation of the strategy requires stronger top-level design and measures, and more concerted efforts.

Efforts should be made to ensure the country’s grain output remains above 650 million tonnes, solve the two key issues, namely seed and arable land, and secure a good start for rural and agricultural modernization, according to authorities.

FINANCIAL RISK PREVENTION

It is important to accurately judge the current financial risk situation as China has seen increased downward pressure in the economy, risks and challenges at home and abroad, and debt risks in some enterprises since the second half of the year.

After years of hard work, the country has made great progress in preventing and defusing major financial risks, and has prevented systemic financial risks.

Authorities have noted that while there are individual issues in the real estate market, the risks are generally under control.

The country’s top legislature has just adopted a decision to authorize the State Council to pilot property tax reforms in certain regions.

The move aims to advance property tax legislation and reform in an active and prudent manner, guide rational housing consumption and the economical and intensive use of land resources, and facilitate the steady and sound development of the country’s property market, according to the decision.

The reasonable capital demand of the property market is being met and the overall trend of healthy development in the real estate market will not change, according to authorities.

interesting development in china regarding developers and overseas investments

https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/27/business/china-overseas-debts-evergrande-intl-hnk/index.html

i would consider this a positive surprise. and a good decision.