From Buoyant Dollar Recovers Its Luster, Underlining Rebound in U.S. Economy in today’s NY Times:

The United States dollar, after one of its most prolonged weak spells ever, has now re-emerged as the preferred currency for global investors. Across trading desks in New York, London and elsewhere, analysts are rushing to raise their dollar forecasts based on the resurgence in the American economy.

This confidence is buttressed by today’s third release of the 2014Q2 GDP report, which revised upward q/q growth to 4.6% (SAAR). [1]

It’s interesting to note where analysts locate the source of the dollar’s strength:

…the increasing push by investors into the dollar can be seen as a favorable report card on the United States economy, highlighting good performance in crucial benchmarks such as growth and fiscal responsibility, and an increasingly competitive position abroad because of a boom in energy exports.

That is the US economy is growing faster, with quantitative/credit easing, forward guidance, a more stimulative fiscal policy (read, less dedicated to government spending cut based austerity measures) — a policy mix many conservatives had decried as leading inexorably to higher inflation (something which has not occurred, and would if anticipated be leading to a weaker dollar).

That being said, it’s not clear that a strengthening dollar is an unambiguous good — particularly in a situation where the output gap is still substantially negative. A higher dollar renders less competitive American goods and services in international markets. Even though the extent of the appreciation is small at the moment, continued appreciation could prove problematic. From Kennedy/Bloomberg:

…this week [Federal Reserve Bank of NY President William Dudley] became the first Fed official to comment on the U.S. dollar since the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index touched its highest level on a closing basis since June 2010. “If the dollar were to strengthen a lot, it would have consequences for growth,” the 61-year-old Dudley, a former Goldman Sachs Group Inc. economist, said at the Bloomberg Markets Most Influential Summit in New York.

“We would have poorer trade performance, less exports, more imports,” he said. “And if the dollar were to appreciate a lot, it would tend to dampen inflation. So it would make it harder to achieve our two objectives. So obviously we would take that into account.”

Determinants of the Dollar’s Recent Behavior

So how much of the dollar’s recent strength is attributable to the change in monetary policy, in itself responding to news about relative economic performance? This is a hard question to answer using the conventional models of exchange rates. The simplest real interest differential model, which relies upon uncovered interest parity and sticky prices a la Dornbusch-Frankel, relies at least empirically on stable processes governing interest rates. (Formally, in the Dornbusch model with sticky prices, all gaps in price levels, real money stocks and interest rates close a proportional gaps).

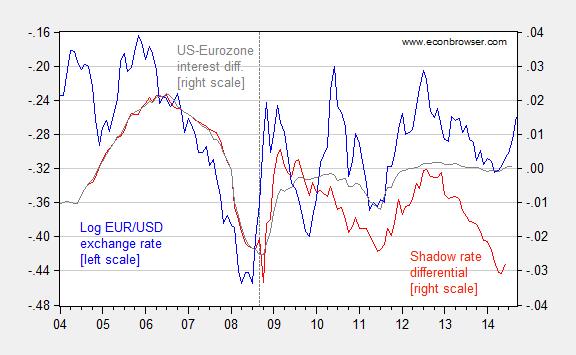

However, recent times have been marked by policy rates at the zero lower bound in the advanced economies. As shown in Figure 1, for instance, the correlation between the euro-dollar exchange rate (EUR per USD) and the observed policy rate differential between the US and the euro area has been pretty low. Given the definition of the variables, the correlation between the blue and gray line should be positive.

Figure 1: Log EUR/USD exchange rate (up is USD appreciation; blue, left scale), and US-euro area policy rate differential (gray, right scale), and Fed funds shadow rate and ECB shadow rate differential (red, right scale). September observation pertains to first three weeks. Dashed vertical line at 2008M09 (Lehman Brothers bankruptcy). Source: St. Louis Fed FRED, and Wu and Xia (2014), and author’s calculations.

In order to get some measure of anticipated future policy rates, I also plot the shadow interest differential for the US-euro area, where the shadow rates are calculated based upon the methodology in Wu and Xia (2014). Notice that the correlation now becomes obvious. Unfortunately, the ECB series has not been calculated out to 2014M08, so we miss out on the most recent months when the dollar has surged against the euro. However, we can guess that the euro shadow rate has likely declined in the wake of the ECB’s moves toward credit easing.

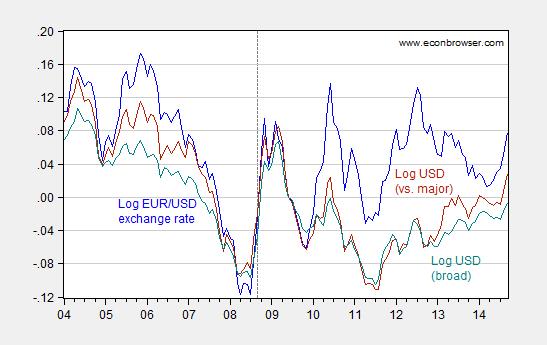

The dollar’s rise has been broader based; the euro accounts for only a share of the trade weighted dollar — 16.2% of the broad index, and 40.4% of the index against major currencies (see [1]). Nonetheless the euro-dollar exchange rate is highly correlated with the broader indices (aside from the period from late 2011 through 2012). A regression of the major currencies index on the EUR/USD exchange rate (in log first differences) over the 2004M01-2014M09 period yields a OLS coefficient of 0.66, adjusted R2 of 0.83.

Figure 2: Log EUR/USD exchange rate (blue, up is USD appreciation), and log trade weighted value of USD against major currencies (dark red), against broad basket of currencies (teal), all series rescaled to 2009M06=0. September observations pertain to first three weeks. Source: St. Louis Fed FRED, and Federal Reserve Board, and author’s calculations.

The foregoing suggests the following first differenced regression (the levels regression specification doesn’t seem to be cointegrated), where I have augmented the “shadow” interest differential with the CBOE VIX [2]:

Δ twxr = -0.001 + 1.173 × Δ (i-i*) + 0.145 × Δ vix

Adj.-R2 = 0.15, SER = 0.015, DW=1.70, smpl 2004M10-14M06, n=117. bold face denotes significance at 5% level. twxr is log nominal trade weighted dollar (vs. major currencies), i-i* is shadow policy rate US-Eurozone interest differential, and vix is CBOE VIX, monthly average of daily data (10%=0.10 latter two variables).

This is a relatively high coefficient of variation for a first differenced exchange rate specification. Hence, I’m relatively confident that the regression captures the fact that changes in real interest differentials, combined with a risk measure, affect the dollar. (I’ll update the regression and Figure 1 when I obtain updated shadow rates for the ECB).

Normative Implications

There’s a bit of triumphalism in some of these reports — see in particular this panegyric by Moore and Kudlow at Heritage, entitled The Return of King Dollar. A stronger dollar induces some expenditure switching away from US goods and toward foreign goods; of course the underlying strength of the US economy will likely swamp these effects, but still output and employment would likely be less than it otherwise would be in the absence of dollar appreciation.

Stehn at Goldman Sachs (not online, 9/23) uses the Fed’s FRB/US model combined with an inertial Taylor rule (1999 version) to simulate the impact of the broad dollar appreciation of 3% since the beginning of July.

…, we find that the recent appreciation (if maintained) would lower real GDP growth by about 0.15 percentage point (pp) in 2015 and 0.1pp in 2016. If the dollar continues to appreciate, these growth effects become more significant at 0.25pp in 2015 and 0.3pp in 2016, as the effect of cumulative appreciation builds in outer years.

Second, the inflation effect of dollar appreciation is negligible. …. The intuition for a very small effect on inflation is that inflation in FRB/US depends primarily on the level of slack in the economy, not the growth rate of output.

Finally, the implications of a stronger dollar for the Fed are limited. Under an inertial Taylor rule, the dollar appreciation observed to date (if maintained) would lower the warranted funds rate by 5 basis points (bp) at the end of 2015 and 15bp at the end of 2016. Continued dollar appreciation would, again, lead to somewhat larger effects.

I’d state this in a slightly different way — the cumulative impact on the level of GDP relative to no appreciation is 0.55 ppts. Whether this is big or not depends on one’s perspective. With the current output gap at approximately -4%, using August 2014 CBO estimates, half a percentage point of GDP is not insubstantial in my mind. Hence, I’d argue that the move toward starting to raise the Fed funds rate and/or other policy rates should be tempered by the impact on the value of the dollar.

For more on evaluating exchange rate behavior at the zero lower bound, see this post and this post. Using Taylor rule fundamentals, here; and a recap on exchange rate models here.

For discussion of the impact of exchange rates on US trade flows, see this post.

A higher dollar helps businesses and consumers boost their consumption more as real prices decline making it easier to make purchases. For businesses, this is real important. The 02-05 housing bubble covered up the decline in that period.

I think people have to understand is, the ECB by “artificially” holding up the value of the Euro, created a weaker dollar, declined business consumption domestically in America and strangled their own economies in Europe. So with the “subsidy” gone, the Euro is falling where it always should have been in the first place.

On a fundamentals basis, the US economy is pretty decent shape.

– inflation is low

– household and corporate deleveraging have ended (if I read the graphs right)

– interest rates are low

– there is slack in the labor market, but not egregious

– the current account is -2.3%, well with post-Reagan historical norms, and increased oil and gas production will continue to improve this ceteris paribus

– the federal budget deficit is forecast by CBO to be less than 3% through 2017

– the price of oil has fallen below the carrying capacity level

I personally think shale oil is making a dent, and one reason that the dollar is appreciating. Russia-related uncertainty is almost certainly also playing a role in Euro / $ rates. And so is the ending of QE.

A stronger dollar should help Europe. That’s where the situation remains most dire, I think. Some American prosperity would help them.

The Rage: “the Euro is falling where it always should have been in the first place.”

There is no “should have been”. This is only “what is”. Every country and central bank manipulates their exchange rates as they see fit to the advantage and disadvantage of the winners and losers in their society that the bankers choose.

“…current output gap at approximately -4%, using August 2014 CBO estimates…”

According to this chart, per capita real GDP is 9.8% below a long-run trend, or about $6,000 a year too low:

http://www.advisorperspectives.com/dshort/charts/indicators/GDP-per-capita-overview.html?Real-GDP-per-capita-since-1960-log.gif

It looks like a sudden and sustained downshift or roughly an L-shaped recovery.

We have a long way to go, through destruction of potential output or raising actual output, to close the output gap.

However, the U.S. economy has performed better than other major economies, in part, because of its exceptional fundamental strengths.

That really means the ‘real’ gap is 2%. Because the CBO takes it off the previous peak. Which is a mistake. If you want 4.5% unemployment, it is 4% gap. If you want 5.5% unemployment, it is a 2% gap.

People make this mistake over and over…….and over again.

From the comment by Stehn at Goldman Sachs:

“Second, the inflation effect of dollar appreciation is negligible. …. The intuition for a very small effect on inflation is that inflation in FRB/US depends primarily on the level of slack in the economy, not the growth rate of output. ”

Surely less exports and more imports leads to slack since it means less demand for domestic goods (in other words, dollar appreciation does lead to less inflation).

Or am I missing something?

Right, but that also makes domestic products cheaper, which helps. Your not thinking right.

Are we talking about inflation or about slack? I was commenting on the stehn quote where he writes that the appreciation will cause real gdp growth to decrease but that there will be almost no effect on inflation. If he is correct that the appreciation has a sizable negative impact on growth (presumably through the trade balance effect) then the appreciation should also cause a decline in inflation because of that same effect. In other words I was pointing out that his conclusions appear mutually inconsistent.

Let me see if I understand with an example of Menzie’s logic. I am interested in what is going on with the water in Lake Mead that feeds Las Vegas. So, I measure the level of water in Lake Michigan and compare it to the water level in Lake Mead. Now I observe that the ratio is getting larger and larger. Obviously the ratio is telling us the water level in Lake Michigan is increasing so the water authorities determine that it must be because there are too many ships in lake Michigan. The authorities immediately plan to introduce more ships into Lake Mead to increase the water level.

Now, those looking from the outside actually have a measure of water level independent of the two lakes called the “meter.” Now, those outside argue that it is obvious that it is not Lake Michigan that is changing but Lake Mead because using the independent measure we quickly see the decline in the water level independent of Lake Mead.

So we have the euro (Lake Mead) and the dollar (Lake Michigan). Is it meaningful to compare the levels of the two to determine whether the economic value of the two is increasing or decreasing? Perhaps we need a common unit outside of both? Is there such a measuring unit? Gold?

When looking at water levels in lakes it is easy to see the foolishness of creating ratios of water levels to make determinations, but with currency we never question the logic of doing the same thing.

Menzie wrote:

That is the US economy is growing faster, with quantitative/credit easing, forward guidance, a more stimulative fiscal policy (read, less dedicated to government spending cut based austerity measures) — a policy mix many conservatives had decried as leading inexorably to higher inflation (something which has not occurred, and would if anticipated be leading to a weaker dollar).

To support his assumption he uses the ratio of two lakes. What if we look at the independent unit of the price of gold? What we see is gold peaked in price in the second half of 2011 then in the second half of 2012 it began a steep decline until mid-2013. Since then it has once again become stable. Is it a coincidence that the price stability of gold is followed by the beginnings of recovery? Also is it a surprise that currency traders are now holding dollars rather than divesting themselves of dollars?

Both Keynesian monetarists and “conservative” monetarists (modern Austrians) have been watching only the water levels. The Keynesians have been pushing to increase the currency level begging for stimulation, while the conservative monetarists have been begging for a decline in the currency level while whining about high levels driving inflation, both slaves to the QTM. But a quick look at a graph of gold tells a story that aligns with economic reality. The fact that massive currency increases since 2000 have not led to prosperity but surrounded the Great Recession like a massive fog, should lead a normally intelligent person to understand that the inflationist theory of prosperity is a failure. Similarly, the failure of hyper-inflation to materialize should tell the conservative monetarists that their QTM theories are also a failure.

Mises tells us it is the exchange value of money that is important. How do we measure that? Hmmmmm? (for those interest in more on this check a graph of the price of gold from 1970-2014. The prosperity of the 1980s and 1990s clearly corresponds to relative stability of the price of gold. When Volker and Greenspan held the currency stable traders could adjust to the failures of the political system and still maintain a level of prosperity.)

“That is the US economy is growing faster, with quantitative/credit easing, forward guidance, a more stimulative fiscal policy (read, less dedicated to government spending cut based austerity measures) — a policy mix many conservatives had decried as leading inexorably to higher inflation (something which has not occurred, and would if anticipated be leading to a weaker dollar).”

Well, it *did* lead to a weaker dollar. Competitive devaluation is why the US is doing a little better than Europe. Now the ECB has stepped in and said enough, and it is going to fight for a weaker euro. Competitive devaluation. Sweden has recently decided to take measures to lower its exchange rate. Competitive devaluation. Japan took big steps over a year ago. Competitive devaluation. Switzerland has put a floor on its currency. Competitive devaluation.

The one policy response to Depresion II has been competitive devaluation. The Europeans are a bit late to the game, but there’s no reason why they can’t play.