Consider this prognostication from 2011:

Americans face the most predictable economic crisis in this nation’s history. Absent reform, the panic ahead is no longer a question of if, but rather when. A deterioration of confidence by investors in government’s ability to pay its bills will drive interest rates up, increasing borrowing costs for government, small businesses and families alike. A vicious cycle of debt will compound upon itself; the available exit options once the crisis hits will be limited; and all will involve pain. (p.59)

Writing about the President’s FY2012 budget:

…Autopilot spending will soon crowd out all other priorities in the federal budget, with spending on Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security and interest on the national debt eclipsing all anticipated revenue by 2025. Borrowing and spending by the public sector will crowd out investment and growth in the private sector. … [emphasis added] (p.56)

Those quotes are from Representative Paul Ryan’s FY2012 “Path to Prosperity”.

It is all the more surprising, then, to consider actual data that has come out over the past three years since publication of that document.

First, consider the sources of saving available to the US economy, by reference to the National Savings Identity:

(S-I) + (T-G) ≡ CA

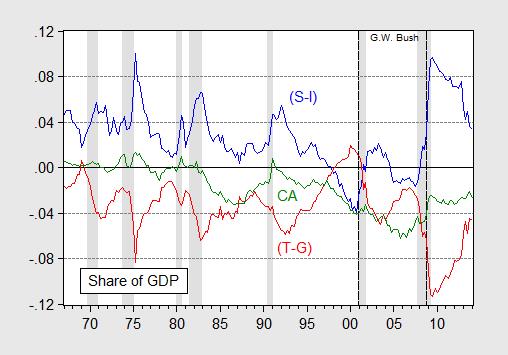

where S and I are private savings and investment, (T-G) is the public sector budget balance, and CA is the current account. Figure 1 shows the evolution of these series, all expressed as a share of nominal GDP (note that I have omitted the statistical discrepancy for the sake of clarity).

Figure 1: Private sector net savings (S-I) (blue), public sector net savings, or budget balance (T-G) (red), and current account (CA) (green), all as a share of GDP. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: BEA, 2014Q2 advance release, NBER, and author’s calculations.

Notice the drastic reduction in the public sector deficit, even prior to the implementation of the sequester in March 2013. The current account balance has improved substantially since the onset of the Great Recession — in line with a conventional macro model that relies on a marginal propensity to import — although it has stabilized at about 2.5% of GDP.

The identity is merely that — an identity, useful for accounting purposes. However, it does make clear that the US is not borrowing as much from the rest of the world as it was during the G.W. Bush years (peaking at about 6.2% annualized in a couple quarters). That is, the rest-of-the-world has thus far been happy to finance the US aggregate saving needs (as well as that of the Federal government — more on that in a bit).

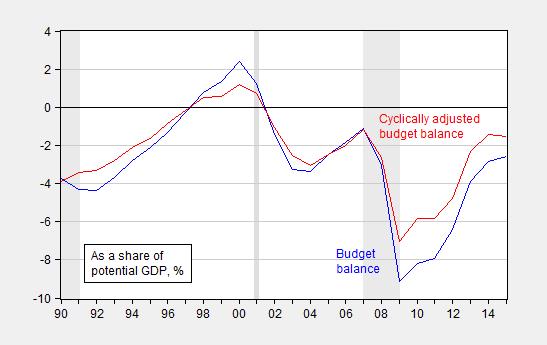

The improvement in the public sector balance, particularly the Federal one, is quite marked if one abstracts from cyclical effects. Figure 2 presents (by fiscal year) the actual Federal budget balance and the one abstracting from automatic stabilizers, normalized by the potential GDP.

Figure 2: Federal budget balance (blue) and balance without automatic stabilizers (red), as percent of potential GDP (%), by fiscal year. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: CBO, Budget and Economic Outlook, February 2014, and NBER.

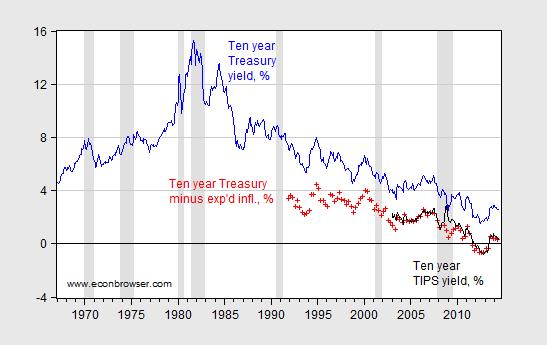

Hence one should not be too surprised that the apocalyptic vision regarding interest rate trajectories held by Representative Ryan in his various “Paths” have not come to pass. In fact real borrowing costs for the US government have remained quite low by historical standards.[1]

Figure 3: Ten year constant maturity Treasury yields (blue), ten year constant maturity yields minus ten year (median) expected inflation (red +), and ten year constant maturity TIPS (black). NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: Federal Reserve via FRED, Survey of Professional Forecasters, and author’s calculations.

Substantial (portfolio) crowding out of private investment as feared by Representative Ryan is unlikely to occur if interest rates do not rise appreciably (relative to the counterfactual); and in fact if investment depends on output, then decreased government spending and hence government deficits might actual yield greater crowding out than the counterfactual (see this post for discussion).

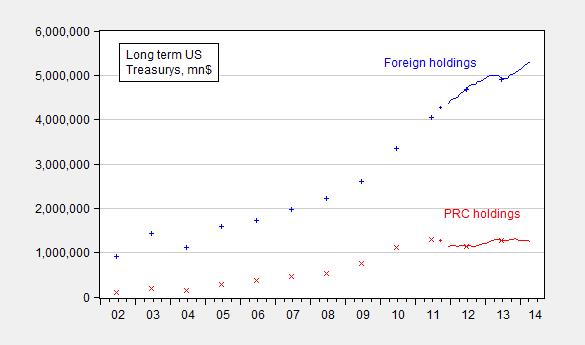

Is it all the Fed’s doing? Fed holdings of Treasury debt (all maturities) were about 18.4% of total publicly held Treasury debt, as of March 2014. Compare this against the previous peak of 17.3% in March 2003, and 24% in June 1974. So Fed purchases are part of the story, but not by any means all of the story. In fact, one might point to another factor as being even more important, namely foreign demand. Thus far the foreign sector (both private and public) seems quite content to continue acquiring US Treasurys, despite the best efforts of some policymakers to drive up the risk premium; see also [2]. Figure 4 depicts foreign holdings of long term US Treasurys.

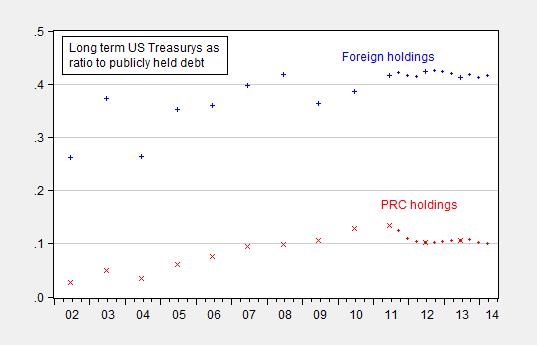

Figure 4: Foreign holdings of long term US Treasurys (blue) and holdings of the People’s Republic of China (red). +,x indicate benchmark data, line indicates TIC monthly estimates. Source: Treasury.

Looking at levels of holdings in dollars can be misleading, given the increasing size of US Federal debt. However, normalizing doesn’t yield a substantially different perspective. The ratio of long term US Treasurys to total publicly held Federal debt has held fairly constant over the past several years.

Figure 5: Foreign holdings of long term US Treasurys (blue) and holdings of the People’s Republic of China (red), all divided by Federal government publicly held debt (both short and long term). +,x indicate benchmark data, line indicates TIC monthly estimates. Source: Treasury, FRED, and author’s calculations.

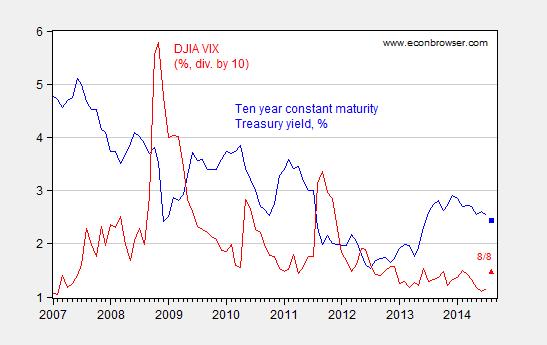

One reason why Treasurys have been so favored during the global financial crisis and aftermath was the safe haven aspect of US Federal debt — not only in terms of default risk, but also in terms of geopolitical risk. To the extent that the VIX proxies for these factors — including geopolitical ones like Ukraine/Russia, one should expect (1) an obvious inverse correlation and (2) an abatement of the demand once risk dissipates. On (1), consider Figure 6.

Figure 6: Ten year constant maturity Treasury yield (blue) and DJIA VIX, divided by 10 (red). Observations for August are for August 8. Source: FRED.

I think there is something to the inverse correlation, in addition to the clear downward trend in the nominal ten year government yield in the background. But it clearly isn’t everything.

Regarding (2), it’s not obvious to me that there is going to be a sustained drop in uncertainty; if that is the case, elevated demand for US Treasury’s may be a persistent condition. That in turn suggests that the idea that long term funding costs for the Federal government (including in real) reverting to long run norms might not occur for some time. By the way, these arguments abstract away from the discussion of secular stagnation, as modeled by Eggertsson and Mehrotra (2014), among others. Secular stagnation merely adds onto the reasons why one should expect low Treasury borrowing costs going into the future.

What are the ramifications of an outcome where Federal funding costs are diminished for an extended period of time? One implication is the growth of government debt-to-GDP is less pronounced than, for instance, what was implied in the CBO scenarios used in Kitchen-Chinn (2011) (see discussion in this post). The urgency for rapid fiscal consolidation is thus commensurately reduced.

“Soon” = “by 2025”, so we’re still a bit early. What were the assumptions underlying the prediction? Were they satisfied or are you bashing an unconditional prediction? Out of curiosity, how did the Democratic budget fare on the prediction front?

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/the-fix/wp/2013/01/22/why-senate-democrats-havent-passed-a-budget/

Tom: If you read the entire paragraph, “soon” appears before “2025”, and the wording is ambiguous — I think intentionally so. But if “soon” in your book is 14 years later, then OK. But 14 =/= soon in my book…

Now, the prediction that Representative Ryan made was that in the absence of drastic spending cuts to make up for tax cuts, we would end up in a debt death spiral. What we eventually got was the sequester; now that is not the President’s budget, but it’s a lot closer to the President’s budget than the Ryan Plan of FY 2012, I hope you agree (if you disagree, then we are living in different universes, and continued discourse is futile). Then we can now ask, three years later — and based upon forward-looking macro indicators — is the US looking more like Greece 2011, or something else?

We definitely look like Greece in 2011…very depressing.

We are emphatically not Greece.

– Unemployment is 6% and falling in the US; it was in the mid-20s in Greece.

– The budget deficit is forecast at 2.8% this year. While higher than I would like, it is still moving in the right direction and within historical norms.

– We have energy; the US is the primary source of increased oil and gas production in the world

– We have competitive products, eg, iPhones.

– We issue debt in our own currency; Greece does not

– We have a floating exchange rate; Greece does not

Growth remains subpar in the US. The Fed is still too involved in goosing the economy, so we have something of a bubble in housing and capital markets, even if inflation remains low. The price of oil is still high, but lower than it has been, and we’ve now had three years to become accustomed to current levels. The current account is in good shape; there is still slack in labor markets; there are no killer bubbles I can see; and inflation is low. This economy should have some running room for the next 12-18 months, assuming no exogenous events (eg, loss of Iraqi oil exports).

Cheer up. Things aren’t that bad on a macro level.

We have energy

Yes, indeed. In addition to oil & gas, the US is a “Saudia Arabia” of both wind and solar energy, and has more nuclear than any other country.

We have far more than enough energy.

When I first read those quotes, I thought that they were coming from this paper.

Rick Stryker: Well, I have a paper (w/Jeff Frankel) which also estimates interest rate reactions to debt levels, in a similar framework to the paper you cite. The point — in the spirit of scientific exploration — is to transcend the established literature to explain recent events. I think exorbitant privilege, safe haven motivations, the safe-assets shortage, exchange rate regime, and perhaps secular stagnation are things that require modification of our earlier views (although I think running a big structural budget deficit when near full employment is a bad thing, as I have written many times before).

With respect to the current account and oil:

In volume terms, our oil imports crested in 2005 at 12.6 mbpd, representing 1.7% of GDP. In dollar terms, our oil imports peaked in 2008 at 2.6% of GDP. During this period, the economy collapsed, and our oil imports amounted to a mere 1.4% of GDP in 2009, somewhat above the “peacetime” 0.8-1.0% (2000-2003) level.

Since 2005, our oil consumption has fallen by 10%, or 1.9 mbpd. Our oil imports, however, have plummeted by 60%, to a mere 5.0 mbpd for 2014. Thus, our adjustment has been provided 1/4 by oil consumption declines, and 3/4 by import substitution through oil production gains of 5.6 mbpd.

Were will still importing oil as in 2005 (thus without a reduction in consumption or the increase in supply provided by the shale surge), our the current account deficit due to oil as a share of GDP would be 2.8%. As it is, the deficit is only 1.1%, that is, within the ‘normal’ range for this economy. In dollars terms, our deficit, on an annualized basis, is $300 bn lower today than it would have been under the circumstances which prevailed in 2005 coupled with today’s prices. The oil deficit is anticipated to fall to 0.9% of GDP in 2015, a very manageable number for the US.

The US is very fortunate, perhaps the most fortunate of the large OECD economies, that it was able to substitute, through its own efforts and endowments, for a commodity too dear to purchase in accustomed volumes and prevailing prices.

How else might an economy adjust? Other strategies would be to reduce consumption (increase savings) and hold investment constant; reduce investment; reduce government spending or increase taxes; or increase exports. Exports could be increased, for example, by creating new products that people wanted (like high-end automobiles or smart phones) or by reducing real wages and competing on cost.

It would be interesting to walk through and see what strategies countries had used, for example:

– Great Britain, which saw oil exports falling just as oil prices were rising, but under a floating exchange rate

– Greece, which is not a material oil producer (and wasn’t), but is subject to a fixed exchange and a lack of competitive exports

– Hungary, not very competitive, no oil, floating exchange rate

UK and Hungary oil consumption fell by 17% and Greece by 32%. (BP data)

How else might an economy adjust?

The best strategy would be to properly price oil, and reduce consumption to an optimal level. Oil products are badly under-priced (and therefore indirectly subsidized) in the US. External costs that should be included include pollution, military and other security of supply costs.

If oil products were properly priced (perhaps around European levels) consumption would drop sharply, and substitutes (which are here, but still becoming familar to consumers) would get a strong boost. Almost everyone would be better off – the exceptions include, of course, oil industry investors, employees and suppliers, as well as a relatively small minority of oil consumers who use disproportionate amounts or have difficulty using substitutes.

So, Nick. We have a largely fixed volume of oil being produced. If you want to consume less, the Chinese will happily consume more.

The European example is telling. Great Britain, where they have reduced oil consumption twice as fast as us, is missing 7 percentage points of GDP compared to the US since the start of the recovery (mostly since 2011 — the surge of US shale oil production).

Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal — oil consumption is down in all of these by 26-32% compared to 2005. Which one of those would you suggest we emulate?

steven, those are all austerity induced countries as well.

Yes, that’s the point I’m making, Baffs. Oil consumption and GDP are highly correlated.

Nick is telling us we should get off of oil, and suggests we follow the example of Europe. Europe has indeed been reducing oil consumption, so that’s good, if you think oil is bad. But the cost of that reduction has been reduced GDP. The countries with the greatest reduction in oil consumption in Europe have, with the exception of Britain, been the PIGS, or the weak performers like Hungary.

Britain is an interesting case, as I note above. It went from being a net oil exporter in 2005 to an import dependency around 50% today. It has cut oil consumption at a faster pace than other countries not in an exchange rate straight-jacket. And it’s missing a good bit of GDP, considering its employment levels.

No oil, no GDP.

“Yes, that’s the point I’m making, Baffs. Oil consumption and GDP are highly correlated.”

no steven, you missed the point. the countries you mentioned were forced into austerity mode with respect to their government financial matters. this was a significant drag on the economy, stalling gdp and the “correleated” oil consumption. when you reduce aggregate demand, it makes sense to see a reduction in gdp and consequently oil consumption.

. If you want to consume less, the Chinese will happily consume more

Yes, and they’ll pay a heavy price for it. They’ve been smart enough to mostly eliminate their price caps and subsidies, but they’re still not smart enough to recognize the heavy costs they’re paying for their oil addiction. Some of those costs are pollution: asthma, lung disease, climate change. Some of them are conflict with their neighbors, as they become more desperate for oil supplies, and come into more conflict with Japan, Vietnam, etc.

Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal — oil consumption is down in all of these by 26-32% compared to 2005.

Sure. They’re more heavily dependent on imports, so their oil addiction is hurting them. A rational response is to cut their oil bills. Heck, if you lose your job, what’s the first thing you do? You cut down on utilities. And, of course, if you lose your job you’re not going to drive as much – reduced economic activity is going to reduce oil consumption.

The bottom line: oil imports are bad for your economy, and cutting them is good.

You’re arguing poverty is good, Nick. I disagree.

On paper, China will add another 2 US equivalents of oil consumption between now at 2030 or so.

This reflects its coal consumption. It added two US equivalents of coal consumption in the ten years to 2012.

You’re arguing poverty is good

No. I’m arguing basic economics: if a good is mispriced, it will be misused. When natural gas prices were kept too low in the US, price signals were wrong. Producers produced too little, consumers used too much (leading to Hubbert’s prediction in the 70’s that gas supplies would soon crash). Similarly, if oil prices are wrong, price signals will be wrong. This is basic economics.

If a department store suffers from shoplifting, or employee theft, they have to raise prices to include that cost. If they have to hire security guards, they have to include the cost of those guards in their internal accounting. If the store managers didn’t include that cost, they’d suffer financial losses and they’d be fired. Similarly, if oil supplies require military protection, that cost should be included in the price of oil. If that cost isn’t, we’re subsidizing oil consumption.

If a car manufacturer finds that a particular paint is toxic, they either eliminate it or they find ways to reduce the toxicity. For instance, they might install additional ventilation. They have to include the cost of that HVAC in their internal accounting. If they didn’t, they’d suffer losses and they’d be fired. Similarly, if oil consumption produces particulate, CO2 and NOx pollution (causing asthma, lung disease, climate change and urban smog), that cost should be included in the price of oil. If that cost isn’t, we’re subsidizing oil consumption.

Right now China is suffering from acute pollution, urban congestion, and increasing in conflict with it’s neighbors, all due to an unwise increase in their oil consumption, due in turn to improper oil product pricing.

We have cheaper and better alternatives to oil. Let’s accelerate their adoption by properly pricing oil.

China will add another 2 US equivalents of oil consumption between now at 2030 or so. This reflects its coal consumption.

I’m not sure what you’re arguing here. I agree that China is burning enormous amounts of coal, and is likely to burn quite a bit more. As a result, it’s cities are choking in pollution – millions of deaths annually are attributed directly to coal pollution. If the price of coal reflected it’s public health costs, the country would be far better off, overall: it’s manufacturing might be a bit smaller, but it’s health would be far better. Overall, it’s income and wealth would be greater.

On the other hand, China recognizes the impact of pollution (both direct and CO2), though they consider that to be a lower priority than crash economic growth. That order of priorities might have something to do with the large number of single males that must be kept employed, lest they start revolutions.

So, China is ramping up wind, hydro and solar (production and consumption) as quickly as it can – faster than any other country. The wind program through 2020, for instance, will cost around $400B – that’ s not nothing.

Oil is mispriced in Europe. It is over-taxed.

Oil is mispriced in Europe. It is over-taxed.

uhmmm…you might want to expand on that, perhaps in a quantitative way.

The average European uses 18% as fuel as the US, for personal transportation. The big kahuna for European oil is diesel for freight, I think. I believe diesel for commercial freight is much cheaper, due to much lower taxes. That encourages commercial freight consumption in a way that’s hidden.

Oddly enough, Europeans import more oil per capita than the US. The US can dramatically reduce it’s imports with more efficient vehicles and increased oil production, but Europe will have to do things that require some inter-country cooperation (which was historically difficult), like standardizing rail systems and moving from trucks to rail.

And as for security:

We pulled out of Iraq. You happy with the result? You think we should let ISIS take over?

I suggest you take a look at this ISIS series from Vice News. Really eye-opening.

https://news.vice.com/video/the-islamic-state-part-1

ISIS wouldn’t exist if we hadn’t invaded Iraq in the first place.

Why are we invading Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran (in 1954)? It’s all about this dangerous addiction to oil.

Our dependence on oil creates war:

“Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill was appointed First Lord of the Admiralty in 1911. With characteristic vigor and verve, he set about modernizing the Royal Navy, jewel of the empire. The revamped fleet, he proclaimed, should be fueled with oil, rather than coal — a decision that continues to reverberate in the present. Burning a pound of fuel oil produces about twice as much energy as burning a pound of coal. Because of this greater energy density, oil could push ships faster and farther than coal could.

Churchill’s proposal led to emphatic dispute. The United Kingdom had lots of coal but next to no oil. At the time, the United States produced almost two-thirds of the world’s petroleum; Russia produced another fifth. Both were allies of Great Britain. Nonetheless, Whitehall was uneasy about the prospect of the Navy’s falling under the thumb of foreign entities, even if friendly. The solution, Churchill told Parliament in 1913, was for Britons to become “the owners, or at any rate, the controllers at the source of at least a proportion of the supply of natural oil which we require.” Spurred by the Admiralty, the U.K. soon bought 51 percent of what is now British Petroleum, which had rights to oil “at the source”: Iran (then known as Persia). The concessions’ terms were so unpopular in Iran that they helped spark a revolution. London worked to suppress it. Then, to prevent further disruptions, Britain enmeshed itself ever more deeply in the Middle East, working to install new shahs in Iran and carve Iraq out of the collapsing Ottoman Empire.

Churchill fired the starting gun, but all of the Western powers joined the race to control Middle Eastern oil. Britain clawed past France, Germany, and the Netherlands, only to be overtaken by the United States, which secured oil concessions in Turkey, Iraq, Bahrain, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia. The struggle created a long-lasting intercontinental snarl of need and resentment. Even as oil-consuming nations intervened in the affairs of oil-producing nations, they seethed at their powerlessness; oil producers exacted huge sums from oil consumers but chafed at having to submit to them. Decades of turmoil — oil shocks in 1973 and 1979, failed programs for “energy independence,” two wars in Iraq — have left unchanged this fundamental, Churchillian dynamic, a toxic mash of anger and dependence that often seems as basic to global relations as the rotation of the sun.”

http://grist.org/climate-energy/what-if-we-never-run-out-of-oil/

A last word on the 2003 Iraq invasion:

“I am saddened that it is politically inconvenient to acknowledge what everyone knows: the Iraq war is largely about oil”

Alan Greenspan, in his 2007 memoir.

Afghanistan had nothing to do with oil, and everything to do with 9/11.

As for Iraq: I agree, and have stated before, that self-determination leads to ethnic cleansing. So, you are left with three choices:

– Self-determination and ethnic cleansing

– Dictatorship

– A re-worked objective function in the form of an FAA.

Pick one.

Afghanistan had nothing to do with oil, and everything to do with 9/11.

Oh, my. We americans seem to forget history very quickly.

There’s a great deal of history, including Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt, the US’s role in the overthrow of an Iranian democracy in 1954 (motivated in large part by oil), and much more. But, I think it’s clear that the UK’s and US’s heavyhanded efforts to shape the ME is the primary fuel for Al Qaeda targeting the US, and 9/11.

Gulf War I caused 9/11 and Gulf War II. Osama Bin Laden has said that 9/11, and the whole Al Qaida movement, is a reaction to the US military presence in the Gulf generally, and Saudi Arabia in particular. The KSA military presence was a direct successor to Gulf War I, and the general military presence is a result of our concern about the stability of oil exports. Finally, part of the reason for Gulf War II was to resolve unfinished business from GW I.

If the OECD were not dependent on oil imports from the ME, is there any credible way to suggest that Gulf War I and 9/11 would have happened?

you are left with three choices… – A re-worked objective function in the form of an FAA.

How about a re-worked objective function in the form of appropriate oil prices?? Don’t we believe in free markets creating an optimal outcome?

Government policy can remain unsustainable longer than the voices of reason can stay in fashion.

There’s no crowding-out when there’s idle capital.

However, is that capital employed more efficiently, to generate growth, through lower taxes or higher government spending?

At some point, interest on the national debt will rise, which will likely cause government to raise tax revenue.

I think, we needed much bigger “middle class” tax cuts, to facilitate a stronger recovery, which would raise tax revenue, and then raise taxes to slow growth. The national debt would shrink as a percentage of GDP.

Steve,

The decline in oil consumption seems to be a factor of economic stress rather than because of efficiency. Once again we may be talking a chicken/egg situation. Did oil prices and consumption cause economic decline or did economic decline cause changes in consumption?

Oil leads, the economy follows. The oil system, as a practical matter, was maxed out until about Q4 2013. We could not have physically produced more oil in any meaningful way. Therefore, the economy could not have been holding back oil production. On the other hand, GDP growth has been off forecasts by about 1%point since 2011. Germany is flirting with recession. Something is holding back GDP growth. We’ve discussed many of the reasons, but they haven’t held up too well. For example, the R&R assertion that deleveraging is slowing growth…well…does it hold up? I don’t think we’re deleveraging anymore.

In the last three quarters, we are beginning to see capacity tightness in oil services easing. But this easing as a result of stagnant oil prices and rising E&P costs, not due to particularly large increases in non-shale supply, that is, the oil majors are beginning to cut back capex because they can’t make the numbers work.

Now, if you can increase the oil supply fast enough, then oil will no longer be a binding constraint. US and Canadian production was up 2.0 mbpd / year (3 mma) in July. Truly astounding. You probably need another 500 kbpd / year to start really whacking prices, but they’re reasonably weak as it is, just now.

By the way, if oil prices stay near current levels and the US current account is as good as it looks, this economy could pick up speed, at least from the oil perspective.

@Steven: “By the way, if oil prices stay near current levels and the US current account is as good as it looks, this economy could pick up speed, at least from the oil perspective.”

YTD SAAR YoY Q3 SAAR Mar-July SAAR

Real retail sales per capita: 1.54% 0.89% -3.7% -0.15%

Ex autos and parts (core) per capita: 0.65% 0.32% -3.1% 0.19%

On a 12-month annualized basis, real retail sales ex autos per capita are at no faster than stall speed and at the same decelerating rate at the onset of the recessions in late 2000-early 2001 and late 2007-early 2008.

Inventories are running well ahead of sales recently, implying a deceleration of industrial production ex mining, i.e., oil and gas extraction.

(Black: real median house price; red: real retail sales ex autos per capita; and blue: real wages per capita)

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/fredgraph.png?g=HFF

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/fredgraph.png?g=HFC

BTW, real retail sales ex autos per capita are following closely the housing market rolling over in a post-bubble deceleration as in 1979, 1990, and 2006, not surprisingly.

If there was a “wealth effect” from the explosion in bank reserves, it was not experienced by the bottom 90-95% of US households, and any increase in “wealth” resulting from rising asset prices is now creating a cyclical price constraint on housing sales. Millennials can’t afford the “American Dream”.

Once the sub-prime auto loan bubble pops, which appears to have begun in H2 2013, housing and real household spending per capita will contract yoy into recessionary territory, if not before the year is over.

Real final sales per capita cannot accelerate under the secular debt-deflationary regime’s energy, debt, and Boomer demographic drag constraints, but most of us don’t yet realize it and the long-term implications, i.e., think Japan.

The Yellen Fed raising rates at the given trend rates of real GDI and final sales per capita is silly. At the given ratios of net derivatives to bank capital and bank assets, raising the reserve/discount rate at the current term structure and yield curve spread would risk episodes like the Barings Bank in the 1890s, Knickerbocker Bank in 1907, utility and other corporate bonds in 1929 and Creditanstalt in 1931, and the Bear Stearns-Lehman takedown in 2007-08.

Since GDP is significantly driven by governmnet spending it would be instructive to see these graphs in real terms rather than a percentage of GDP. As your earlier graphs have shown during periods of war the G component of GDP increases significantly; even capital goods sales increase as government buys war materials from the private sector.

Of course the private sector is not borrowing as it did during the Bush years. The reigning economic paradigm of Keynesianism drove the wagon train into this box canyon, with a wall of debt on all sides now trapping it. Sensible people now recognize this and are trying to pay their debt down.

As for the US current account, it has cumulatively accrued $8 trillion more debt to the rest of the world this past 15 years. And it’s visually obvious from the graph that progress in reducing the current account has been pitifully slow the past four.

Of course other nations have been quite happy to finance US buying of their goods. It creates jobs for their people, and gives them a convenient place to put their surplus to work with the reward of annual interest payments on the horizon as far as the eye can see for which they no longer need lift a finger. Moreover, with each increment of debt they gather to themselves even more geopolitical clout and control. In the process, continuing to hollow out the once mighty US middle class, many of which are dazed by it all and do not even yet comprehend.

Of course there is another side to the story of historically low US government borrowing costs. That’s the rising rate-wall this country must now climb as interest rates start their journey back to normalization. A journey out of the largest unmapped ocean of artificially-created money the world has ever seen. An ocean made even more dangerous by global systemic risk.

And the nation’s surplus. Which otherwise gets no mention. The surplus being the wellspring of growth, the necessary set-aside (abstinence from consumption) that enables the flow of investment that embeds new technology into the stock of physical capital, which along with know-how is the source of all productivity growth. Net national saving as a percent of GDP this recovery has dwindled to the vanishing point of 0.3%. A couple magnitudes below what it needs to be in a healthy economy.

Finally, it is a sad state of affairs to point only to the silver lining that the funding costs of the federal debt may not return to long-term norms for some time. Since this sliver is dwarfed by the dark ominous cloud of geopolitical risk and secular stagnation which surrounds it, and is its very cause.

“The reigning economic paradigm of Keynesianism”

I must have woken up in a parallel universe.

“Sensible people now recognize this and are trying to pay their debt down.”

And when the private sector is trying to net save, the government should…ah, screw it.

Prof. Chinn,

Rep. Paul Ryan and many others believe that investors worry that the government may not be able to pay its bills, as you quoted:

“A deterioration of confidence by investors in government’s ability to pay its bills will drive interest rates up, increasing borrowing costs for government, small businesses and families alike.”

You refer to Uncle Sam’s debt as a safe haven, and although you are writing in passive voice, you are referring to the world’s investors when you say:

“One reason why Treasurys have been so favored during the global financial crisis and aftermath was the safe haven aspect of US Federal debt — not only in terms of default risk, but also in terms of geopolitical risk.”

Do investors worry about Uncle Sam’s ability to pay his bills, or do they consider him to be that borrower who is most likely to pay his bills?

Are there any circumstances in which Uncle Sam would be unable to meet his obligations, assuming he wanted to meet them?

Why do your investors consider Uncle Sam’s debt to be a safe haven? Do bond vigilantes exist?

In June 2014 the ECB announced that it would impose negative interest rates on depositors.

This is argued from two perspectives. One the claims is that it will force banks to lend out excess reserves, and two, the claim is that the risk of deflation is so great that unprecedented action is warranted to prevent it.

First, when a bank lends out money it always returns to the banking system. Negative interest rates forcing the lending of excess reserves is silly on its face.

Secondly, inflation and deflation are not really economic concepts, though they are Keynesian and monetarist illusions. Money is a tool. That tool can be distorted and its usefulness can be reduced by increasing its measurement or decreasing its measurement but doing either impedes the usefulness of the tool.

But what is always willfully ignored with ZIRP or negative rates is that it forces holders of money to speculate. Negative interest rates will drive banks into purchasing more government bonds. This seems to be the real motivation of this action. It is the modern innovation of “coin clipping.” The central banks do not create money and give it to government to spend. The CBs create money and then lend it to banks to buy government paper which does the same thing but is hidden from direct view and gives the CB plausable deniability in relations to the transaction. “What me? I didn’t give them any money.”

I did not close my quote on the post above. it is actually only the one paragraph. We do not have the ability to edit posts. If you do please close my html command.

“But what is always willfully ignored with ZIRP or negative rates is that it forces holders of money to speculate.”

I would disagree. we do not force holders of money to do anything-they have free will to make choices. you may not like the choices made, but nobody is forced to speculate. perhaps one should accept the notion that we are in a low return environment where past methods of making money off of money may not longer be the best route forward-or one’s timeline on evaluating overall performance needs to change. you are frustrated with the current environment because you continue to live in past metrics-those need to change. i was rewarded by not buying a house during the bubble, while others said i was foolish for not cashing in on the housing appreciation. but this allowed me to accumulate nimble assets to be used during the bust-when things are cheaper. its a simple example of why you are not required to speculate. people use that as an excuse for their lack of conviction and short time frame. in a low return environment you actually have to work for your money, not live off your past. you need to value your capital a little bit differently than in the fast times.

Here’s a story from Huffington Post on Hungary’s Viktor Orban, who is calling for “illiberal democracy”.

This is exactly, exactly, why you want an FAA.

Steven,

You often mention the idea of an FAA without an explanation, or link to an explanation. A little googling didn’t find a good explanation.

Could you provide that link?

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/marco-valerio-lo-prete/viktor-orban-liberal-democracy_b_5668259.html

The Three Ideology Model (TIM) and a Fiscal Accountability Act (FAA)

I use the Three Ideology Model (TIM), which derives from my experience in post-socialist Hungary, dealing with ex-communist managers, state-owned entities, and everyday people.

The TIM posits that there are three objective functions in government corresponding to long established ideologies, themselves the result of evolutionary pressures. These are:

– Liberalism (Liberté, Fr Rev; Freedom, per Hayek): The unit of analysis is the individual; the objective function is the maximization of the utility of the individual. Most of the economics we learn is based on this objective function. It underlies almost everything Jim might write. Liberal corresponds to ‘principal’ in principal-agent theory.

– Conservatism (Fraternité, Fr Rev; Community per Hayek): The unit of analysis is the group; the objective function is the maximization of the utility of the group. If you’re in the army or a football team, this is what it’s all about. There is no developed theory of conservatism. In my model, it corresponds to ‘agent’ in principal-agent theory.

Principal-agent theory suggests an inherent schizophrenia in the individual, between personal liberty and social responsibility. Libertarians usually implode on these issue (eg, should the government provide roads or justice). But all of us fundamentally are torn between maximizing our own interests and our social obligations and rights. (If you’re not, I suggest you marry and have children.)

– Egalitarianism (Égalité, Fr. Rev; Equality per Hayek): The unit of analysis is usually the individual, but I’m not sure that egalitarianism is only one thing. I could make the case the that egalitarians are weak social conservatives, ie, those at the bottom of the pecking order clamoring for more redistribution. But they can also be conservative anarchists, like Stalin, implementing a dictatorship (a conservative notion) of the proletariat (an anti-liberal notion). The conceptual basis of egalitarianism is the notion of static declining marginal utility of wealth and income (DMUWI), which is theoretically sound in an ideal world. Menzie is an egalitarian.

If you read the comments here or on any other econ or politics blog, you will note that the commenters and comments tend to fall very consistently into one of these camps. Thus, politicking must be a very important aspect of ideology, which suggests that these ideologies cannot easily be reconciled by analytical means. Ideology is thus a matter of values.

This is turn suggests that ideologies supersede economics. They sit atop the profession. They are what economics tries to optimize. Thus, politics is not about policy. Politics is about which ideology will be ascendant, and that in turn is a function of values, which in turn are influenced by both objective factors (Republicans are richer, on average) and indoctrination. Hence the consistent passion (often ungrounded by balanced analysis) in the debate.

Now, in principal-agent theory, if an agent is given more than one objective function, and if these conflict, then the agent (politician) will be freed to pursue his own agenda, as the principal (the voter) will de facto lose control over the politician. (This explains, by the way, why SOE’s tend to be loss-making.) Thus, in this framework, if the objective function for the agent is not explicitly defined, then you will see a non-market failure in group governance, that is, the agents themselves can choose which objective function to follow. This can lead to paralysis and a willingness to decrease group utility in the interest of a particular set of political actors. In Hungary, we refer to this latter phenomenon as “killing the neighbor’s goat.” Put another way, the debate over the objective function (defining appropriate policy) is commingled with the execution of the objective function (voting for and funding projects). Strategy is not separated from execution, and thus execution is poor.

Now, how does the principal control the agent? In business, that’s simple: We motivate the principal behind the agent . In other words, you get paid for doing your job. We do not ask the employee to deal with customers and administration because of their personal sense of commitment to the company, but rather because they are paid to do so, and we don’t really care very much if they’re committed to the company or not.

By contrast, we tend to appeal to political agents (politicians) to act on the basis of their agency roles, that there should be “political will” or they should “do their duty” and “put aside partisan interests.” No one asks burger flippers at McDonald’s to exercise political will. They pay them to flip burgers. Indeed, the term “political will” is virtually unknown outside the political sphere. Have you ever heard of a business executive lacking the “political will” to downsize? Businessmen do not downsize because it is fun. They do it because they’re paid to maximize profits. Any businessman or consultant would consider an appeal to personal responsibility to be a thin reed (indeed! that is the very tactic of the egalitarian!). ” You should do the right thing! Even if it costs your career!” Well, this is just plain nonsense, and time and time again we see that politicians do not act to maximize social utility.

Therefore, we should seek to motivate politicians as we do individuals in any other trade: we pay for results. That is, we do not make an appeal to the agent to behave responsibly because he has in theory accepted some role (“Be a statesman!”), we motivate the underlying individual by sharing our own enhanced utility with them.

Now, since I am primarily a classical liberal (well, and a conservative), I believe the primary objective function of government is the sustainable prosperity (a liberal notion) of the nation (a conservative notion). Therefore, I want an objective function which rewards politicians for providing that, which I define as GDP growth (the profit of society) – increase in government debt.

I personally would pay $2,000 per year in bonuses for 3% GDP growth and no growth in government debt. I believe my family and I (as well as the broader nation) would prosper under such a system (which we last saw under Bill Clinton, by the way). But my formula actually calls for a sum of $10 / household / year for such an outcome, such that:

The bonus pool for all members of Congress and the Executive branch (figure 600 people) would equal

i) (GDP growth – growth in government debt)

ii) times 0.25%

iii) divided by 600 members of the legislative and executive branches.

So, nominal GDP is around $18 trillion; 3% growth would be around $540 billion; the deficit this year is anticipated at $460 bn; the bonus pool basis is thus $80 bn.

Of this amount, the bonus pool would be 0.25%, or $200 million; bonus per legislator would be around $330,000. There would be vesting and offsets. Also note that, if the deficit could be brought to zero, the bonus rises to around $2 million per legislator.

You can see the biases of such a system:

– strongly favors a balanced budget (or explicitly declining debt, with higher taxes or lower spending; note that it implicitly incorporates the notion of fiscal multipliers)

– pro growth regulation and macro policies

– pro education, provided it has a positive ROI

– anti-war

– anti-prison, pro-rehabilitation

– anti-transfer payments

– pro-immigration

– pro-infrastructure (if it has an ROI more than risk-adjusted cost of long-term government debt; social return on CT TWP expansion is 25%+)

– pro optimization of government role in society (ie, government should focus on what it does best, outsource the rest)

– pro-social order and stability

– pro peaceful cohabitation with minorities (wouldn’t that be nice in Iraq?)

– vesting and offsets against future bonuses (discounts) will tend to make it favor longer-term stability

That’s it in a nutshell.

Viktor Orban, Hungary’s Prime Minister, says that he favors “illiberal democracy” of the sort found in China, Singapore or Russia, because democracies cannot handle the challenges of the modern world. In my model, Orban is correct, as there is a specific non-market failure in democracy as practiced today. If the agency role of the politicians is under-developed (that is, if they are unwilling as a group to put their long run interests of society ahead of short term parochial interests), then democracy may indeed by unable to cope with situations outside a “business as usual” setting, which is where Europe finds itself just now. Why is faith in democracy failing? Because it is unable to cope with the situation in Iraq, or Hungary, or Russia. That’s how fascism arises, when people lose faith in the ability of a participatory system–not in individuals, but in the system as a whole–to deal with a displaced economic or social situation. In such an event, they may be drawn to other models of agency, including autocracy and theocracy. In the former case, the benefit is the ability to act decisively (Hitler was certainly decisive, so is Orban). In the latter case, it is the belief that agency is being forced upon or accepted by leadership because it comes from a higher force, God. Religion is the force restraining the agent’s pecuniary interest and guiding governance.

Look around the globe. Does the current world order look durable? To be truthful, it does not feel like it. It comes down to China, in my opinion, and whether leadership there believes their interests are better served by war or peace. I think they are torn. But if China does not stand up for stability, then I think the outlook is pretty grim. If Russia and Iran believe China is willing to stand at the roulette table, then they will, too.

So, I think we better put our sensitivities aside, and start taking a cold, hard look at western governance and the innovations which can be attempted to stabilize national and global systems.

That’s how fascism arises, when people lose faith in the ability of a participatory system–not in individuals, but in the system as a whole–to deal with a displaced economic or social situation. In such an event, they may be drawn to other models of agency, including autocracy and theocracy. In the former case, the benefit is the ability to act decisively (Hitler was certainly decisive, so is Orban).

Is there any evidence that autocracy works better?

Certainly, there have been many autocrats that failed their people miserably. Hitler did. So did Stalin, Mao, Czar Nicholas, King George III, the French kings, etc., etc., etc. Research suggests that democracies are much less likely to start wars than autocracies.

There may be a few autocracies that appear to work well currently, but I suspect that demagogues simply have better “marketing” in bad times.

————————-

Autocratic Russian communism, as well as the related governments in Easter Europe, certainly didn’t function well. I’m not sure that reacting to those is a good idea. In other words, doing the opposite of what they did probably isn’t very functional either.

————————–

Economic production and growth is the main job of the private sector. Much of the job of government is taking up work created by market failures: backstopping the private sector, and handling what it fails at. Limiting government to a support function of the private sector would be an enormous mistake. Really, it would mean that the private sector succeeded in eliminating democracy, and achieved what it has always wanted: control of government and elimination of the influence of other constituencies.

Handling pollution in general, and Climate Change in particular, is a clear example. The private sector has failed miserably, and it’s not really it’s fault: setting the rules is the job of the referees, not the players. For example, no single hockey player will wear goggles, because it gives a competitive disadvantage. They will happily wear protective eye-wear if *all* the players are required to.

I don’t disagree, Nick. I am not endorsing autocracy, but rather highlighting that democracy risks failure, because there is a non-market failure astride the government’s objective functions.

By way of illustration, here’s an interesting article on Italy’s outlook from Edward Hugh at Fistful of Euros: http://fistfulofeuros.net/afoe/the-italian-runaway-train/

Is democracy working in Italy, Nick? It seems to me that democracy has brought Italy pretty close to the end of the line, that is, unsustainably in debt and unwilling to reform. So what’s Renzi’s objective function. Hugh says this:

“While Renzi has waxed eloquently about transforming Italy, buoyed on by the results of the European Parliament elections he seems more concerned with pushing through electoral reform – which is obviously needed but is not perhaps as pressing as the growth and debt problem – leaving the suspicion that he is more interested in getting re-elected than anything else.”

“To date Renzi’s government – which is almost operating outside real historical time in terms of economic issues – has made little progress on the sort of reforms which might help the country recover some kind of growth, like those to the judicial system and the labor market. The only measure that could be considered vaguely “pro-growth” that his government has enacted was the 80 euro bonus delivered to low-wage workers hasn’t boosted the economy as its proponents claimed. The measure seems more cosmetic – comparable with José Luis Zapatero’s ridiculous “Plan E” in Spain – and only reinforces the impression of politicians fiddling while Rome burns.”

“The Italian Prime Ministers reluctance to tackle the labour market issue is understandable. Any attempt to really change Italian labour law would be deeply unpopular on the left (and even among many in his own party) and a direct clash with Italy’s unions would surely cost him votes if his plan is to hold elections after passing a new electoral law. More fiddling while Rome Burns.”

Thus, we can pretty plainly see that Renzi’s objective function is political acceptability, notably to a critical electoral group, rather than sustainable prosperity for Italy as a whole. How long does Italy tolerate this until fascism looks like an acceptable alternative? If we consider Italy, is Orban wrong in his critique? Doesn’t seem that way.

And yet. As you point out, dictatorship rarely ends well.

So, we are faced with crises which democracies seem unable to manage, on the one hand, and a desire to avoid fascism or dictatorship on the other. Right now, Menzie’s or Jim’s or your thinking is, “Well, democracy will muddle through somehow.” That’s your working assumption. Are you sure that’s right? The last time we had democracy in this sort of crisis, it was followed by World War II. How confident are you in your assumption? Personally, I am not a gambler, not with this sort of stuff. I want–and indeed, propose–tools to address visible principal-agent problems of the sort we see with Renzi. Solving this issue is not difficult, if you have the proper mindset.

democracy risks failure

I think everyone knows that. It’s easy to find examples of mediocre democracy. Heck, very few people feel that their government is optimal.

Surely everyone knows the old expression: “Democracy is the worst form of government…except for all the others.”.

democracy has brought Italy pretty close to the end of the line

Things could be far, far worse. They haven’t declared war on anyone, unlike some others…

Renzi’s objective function is political acceptability, notably to a critical electoral group, rather than sustainable prosperity for Italy as a whole. How long does Italy tolerate this until fascism looks like an acceptable alternative?

This is contradictory. How could Italy choose fascism, if unions and the left are so powerful? If they aren’t so powerful, wouldn’t simply overriding the unions be a logical, far more moderate first step?

The last time we had democracy in this sort of crisis, it was followed by World War II.

I’d describe that as excessively alarmist.

World Wars I and II (WWI, part 2) was started by dictators. Germany and Japan were hell-bent (literally) on growth through conquest.

Japan never had a democracy. Germany’s democracy was very new & fragile – it was destroyed by France’s disastrous demands for excessive reparations, not by voters’ lack of faith in democracy. Of course, panic about the USSR didn’t help: industrialists (in Germany, Europe and the US) supported Hitler to create a weapon aimed at Stalin (notably, autocrats both).

——————————–

Democracies are very far from perfect, but they do “muddle through”.

I do agree with one element of your suggestion: politicians are underpaid. If we paid them better, they’d be better insulated from special interests’ corruption. Of course, such reforms will be resisted by the special interests…

the crowding out just points the government towards using the monetary tool isnt it. and with low rates/liquidity trap, they use quantitive easing, which leads to crowding out…

one big vicious cycle.

– sean from qeducation.sg

sean, there really is no evidence of crowding out. you are applying a theoretical solution to a problem that does not exist in reality.