One of the most interesting papers presented at the Jackson Hole conference was written by Alan Auerbach and Yuriy Gorodnichenko, entitled Fiscal Stimulus and Fiscal Sustainability.

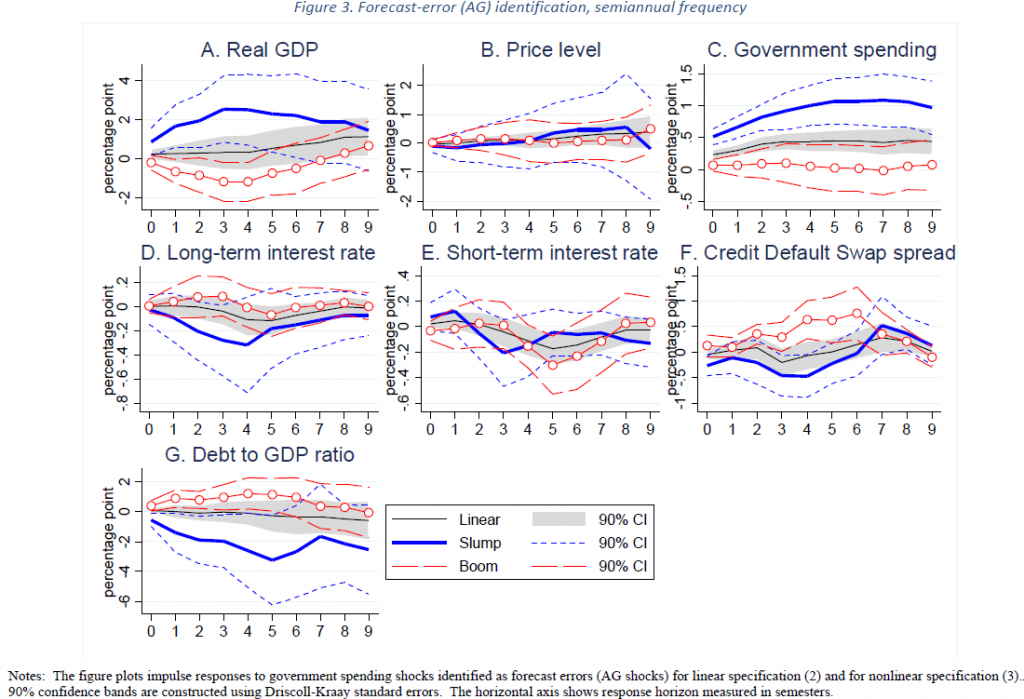

A key takeaway is that fiscal stimulus, during a slump, is likely to reduce — rather than raise — the debt to GDP ratio. This point is highlighted in Figure 3 in the paper, which shows impulse response functions for a shock to government spending.

The red line indicates the debt-to-GDP ratio rises if there is a positive spending shock during a boom. The blue line indicates the ratio falls during a slump. The 90% confidence interval indicates this latter effect is statistically significantly different from zero for up to a year and a half (the frequency is semi-annual). This occurs partly because of the strong government spending multiplier effect that shows up during slumps, discussed in this post.

Interestingly, credit default spreads also decline, as do long term interest rates — although these effects are not significant at the 90% level.

Broadly speaking, similar patterns are obtained using Blanchard-Perotti identification scheme, or using IMF identified spending shocks.

So what remains of the idea of contractionary fiscal expansion? I’d say that the results put yet another nail in the coffin in the idea that typically fiscal contractions lead to economic expansions. However, as came out in the Q&A session, it is possible that expansionary contractions might be more plausible for highly indebted economies. But that’s a big if.

Jason Furman’s excellent discussion of the Auerbach-Gorodnichenko paper concludes that if a recession is severe, one cannot afford to not undertake fiscal expansion. In fact, fiscal space is irrelevant to the question of whether to stimulate or not under such conditions (assuming debt is not too high).

In other words, the people who argued against the ARRA in 2009, and for austerity in the GIIPS, should definitely read this paper. (In case you forgot, that includes Casey Mulligan, Ed Lazear, Keith Hennessey, and Richard Posner, among others.)

By the way, the results also suggest that a big fiscal expansion (tax cuts, defense boost?) at full employment is ill-advised.

[The next post will cover the trade/growth/inequality discussion at Jackson Hole.]

However, are we really at full employment? A significant corporate tax cut in particular may raise real GDP growth from slightly more than 2% to 3%.

https://taxfoundation.org/what-evidence-taxes-and-growth/

“A significant corporate tax cut in particular may raise real GDP growth from slightly more than 2% to 3%.”

Really – you got this from Bill McBride’s survey of the literature? I got – opinions differ.

Sure, opinions differ, like Reaganomics and Obamanomics.

In my experience, people who use terms like “reaganomics” or “obamanomics” contribute nothing but overly simplistic characterizations, at best, or ridiculous fairytales, at worst.

Your lack of experience is not my problem.

I am unconvinced by this, Peak. GDP growth decomposes into population growth and productivity growth.

The working age population of the US is slated to grow by 0.3% per annum to 2030. To get 3.0% GDP growth, you need 2.7% productivity growth. We haven’t been anywhere near that in recent times. Thus, the corporate tax cut argument hinges on the notion that somehow a tax cut will make companies invest much more in productivity gains, assuming these are readily available at all. I have my doubts.

Corporations actually pay very little in taxes as a percent of GDP, only 1.6%, whereas income and payroll taxes are collectively 14.5% of GDP. There’s just not a lot of water in the corporate tax well. And we’re running a budget deficit at 3.6% of GDP, with no prospect for improvement.

So your choices are

1). Leave corporate taxes neutral but rearrange the components (more for wine, less for food, but same tab overall). If you can find 51 enthusiastic votes for reshuffling the deck chairs, go for it, but I have my doubts.

2) Raise corporate taxes net while reducing the tax rates but eliminating deductions

If you can find 30 Republican votes, much less 51, let me know.

3) Reduce corporate taxes and let the deficit expand.

This is exactly where Menzie’s full employment, NAIRA argument takes us. I don’t see the Freedom Caucus signing up for this. This scares me though, because this is where a Furman-type argument takes us.

Of course, you have Cohn saying that tax reform will raise the tax on the wealthy. I am sure the Freedom Caucus wants to be remembered as the guys who raised tax rates–especially on Republican donors.

Put it all together, and I think the case for tax cuts — while I would ordinarily support them — is simply not compelling under the circumstances. Moreover, I don’t see a path to passage in the Congress.

Once again, the Trump administration is chasing its tail, because it is playing the cards it wished it had, rather than those which have actually been dealt.

Steven, the research contradicts your belief. For example, a temporary tax cut is one-third as stimulative as a permanent tax cut, and the tax multiplier, particularly for corporate and income taxes, is higher than the spending multiplier. A permanent lower corporate tax rate will raise private investment and boost productivity. A corporate tax cut may be most effective in raising GDP growth. Perhaps, U.S. corporations avoid domestic investment, because of the high U.S. tax rate.

There was a lot of private investment in the housing market before the “Great Recession,” which spilled over into other industries. However, we haven’t had that in this recovery. A corporate tax cut may spur domestic investment in almost all industries or firms.

Peak –

I’ve run a comparison of tax rates versus GDP growth for the US v OECD peers.

The conclusion:

“If we regress tax rates against GDP growth, we in fact find that a higher tax rate is associated with a higher rate of GDP growth.. But not much higher. Each 10 percentage points increase in taxation yields a 0.1% (pp) increase in GDP growth. Effectively nothing, confirmed by an R2 of 0.007. This leads us to conclude that corporate tax rates and GDP growth in the advanced economies are essentially unrelated.”

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2017/9/2/corporate-tax-rates-and-economic-growth

You need to control for other explanatory variables. The economic literature shows a negative correlation between corporate taxes and investment. For example:

https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/~/media/GIAWB/EnterpriseSurveys/Documents/ResearchPapers/Effect-of-Corporate-Taxes-on-Investment.pdf

And, American manufacturing is very important to the economy:

“American manufacturers are responsible for more than two-thirds of all private sector R&D, which ultimately benefits other manufacturing and non-manufacturing activities. More than 90 percent of new patents derive from the manufacturing sector and the closely integrated engineering and technology-intensive services.

America’s manufacturing innovation process leads to investments in equipment and people, to productivity gains, the spreading of beneficial technology to other sectors, and to new and improved products and processes. It is an intricate process that begins with R&D for new goods and improvements in existing products. As products are improved in speed, accuracy, ease of use, and quality, new manufacturing processes are utilized to increase productivity.

The ability to fund R&D comes largely from the profits that a company can invest back into its business. Thus, the available cash flow of manufacturing companies is closely linked to their ability to conduct R&D as well as make capital investments.”

According to the National Association of Manufacturing:

“A more competitive tax code would help U.S. manufacturers expand their operations and build new facilities. Our outdated international tax system and high tax rates on business income means that manufacturers are at a disadvantage when facing foreign competition.”

Peak –

The paper you cite uses 2004 data. If it were 2004, I might be inclined to agree.

With the economy materially at full employment and interest rates low and equity valuations high, I simply don’t feel that companies are constrained in their capacity to borrow or expand. They are increasingly constrained by a lack of labor, but a tax cut does not create more workers.

But let’s allow an effective corporate tax break of 0.4% of GDP, that is, an effective tax burden reduction of 1/4. Is there a plausible mechanism by which this leads to 0.8% sustained GDP growth? I am hard pressed to see it.

I am not opposed to bringing the corporate tax rate down to 25%. I think that aligns us better with the rest of the OECD. So, sure, but I have little confidence that this will prove some sort of elixir for the US economy.

Given that we are near full employment, I would assume such a tax cut would have no effect on the economy, which means widening the deficit by about 10% to 4% of GDP. If we do that, I would like to see offsetting spending cuts at a minimum, really from healthcare.

Up front confession – I did not read the paper yet. I go by Menzie’s comments.

Comment 1: paraphrasing Jason Furman comments, Menzie says: “In fact, fiscal space is irrelevant to the question of whether to stimulate or not under such conditions (assuming debt is not too high).” This seems to me somewhat contradictory, either fiscal space is irrelevant (as in, “it does not matter”) OR debt is not too high. Of course, if you do not have debt, you can run big deficits and hope (emphasis on “hope”) that you will repay the debt in expansionary times. In other words, fiscal space is given by the level of debt, so for Jason Furman to claim that it is irrelevant, he contradicts himself.

Comment 2: fine, let us buy the argument of the paper, that issuing debt is “good”. Why not issue 100 quatrillion of debt? Or even more? Or is there a limit? Because, the way I was taught economics is that life is full of trade offs, which is the heart of economics; but it seems to me that this paper is arguing (I have to read it – again, I confess, I did not read it yet) that here is a huge arbitrage opportunity left on the table.

And my instincts as an economist are that arbitrage opportunities do not exist. My instincts are that there are trade offs, and issuing debt is not a free lunch.

Comment 3: Menzie asserts: “By the way, the results also suggest that a big fiscal expansion (tax cuts, defense boost?) at full employment is ill-advised.” What is full employment? Let us perform a theoretical, very hypothetical, thought exercise, very simple. Suppose we have an economy with millions of working age people, but they all withdraw from the labor force. And only 1 person remains working. And this person has a job. We are in full employment, right? Because, the other people just withdrew, and by the BLS definition, they are not in the labor force. In this stupid, simple economy, is that really full employment? I am not so sure. But again, I did not read the paper.

Manfred: Apparently I did not do justice to the paper in my summary. I reiterate – read the paper.

Conceptually, full employment is when factors of production are utilized at a rate such that inflation does not accelerate (a mainstream textbook definition — I rule out multiple equilibria for purposes of pedagogy).

Menzie:

“Conceptually, full employment is when factors of production are utilized at a rate such that inflation does not accelerate […]”.

Ok, fine. But are we at full employment in the US? Your definition is silent on this. Your last sentence in the original post suggested (maybe I am interpreting it wrong, forgive me if I do) that the tax cuts that Trump et al are proposing are ill-advised, because, as you claim in that sentence, we are at full employment. Maybe your assertion was a generic one – in that case, sorry. But *if* it was a criticism of current policy proposals hovering around Washington, then my comment stands. There are many commentators who argue that we are not in full employment (of people, not sure about other factors of production, like capital). Because so many people just left the labor force. And thus, so the reasoning, they want to draw such people back into the labor force.

Manfred: Sorry, in other posts, I have asserted that currently we are within a percentage point or so (below) potential GDP. Apologies for not explicitly footnoting to specific previous posts. I will also note IMF, OECD, CBO estimates are in this range, with the Fed typically with a smaller (in absolute value) estimate.

When do we stop fiscal expansion? “Conceptually, full employment is when factors of production are utilized at a rate such that inflation does not accelerate.”

This then delivers the fiscal policy of Japan. Japan has had a very low unemployment rate for a long time, but has struggled to increase its inflation rate. In the meanwhile, it has run up an enormous debt, about 210% of GDP–and yet still no inflation. Therefore, there appears to be no reason to curtail the deficit in terms of fiscal stimulus. Japan is still under the NAIRU limit. Running up a debt over 200% of GDP is just fine by this rule, and therefore a US debt at 77% of GDP is no problem, and there is no reason not to blow out the deficit to 2030 to make, say, the fondest wishes of Obamacare come true.

Isn’t that right, Menzie?

In other words, the people who argued against the ARRA in 2009…

That also includes the usual suspects at this blog who argued against the ARRA…I suspect more out of tribal loyalty to the red team than actual macroeconomic knowledge.

Yeah, slugs, John Taylor, Robert Barro, John Cochrane, and others, they are all stupid dummies, right? They all opposed a major stimulus package, but, they are all just very stupid people. They know nothing about macro, they know nothing about nothing, they are all just robots of the Koch Brothers.

I shiver of what you teach your students.

Manfred John Taylor’s criticisms were stupid. He’s a smart guy, but smart people can say stupid things. As to Robert Barro, failing to notice the effects of a ZLB is a stupid error. And his empirical work on fiscal multipliers shows that he does not understand the economic differences between government authorization, government obligation and government disbursements. As a result, he gets counter-intuitive results because he gets the lags wildly wrong. That said, Barro at least has a medical excuse, so I don’t want to be too hard on him. John Cochrane…well, what can I say? His main problem is that he builds complex models that are all based on ideal and unreal assumptions. Ditto with Ed Prescott and the late Allan Meltzer. They’re all much better at finance than macro.

But note that I wasn’t talking about professional economists; I was talking about the Tea Party types that regularly commented here about the need for fiscal austerity. Strangely, those folks seem suspiciously uninterested in fiscal deficits now that a red team player is in the White House. Are we at full employment? I don’t know. If not, then I think we’re pretty close. But we’re surely a lot closer today than we were in 2009 when all those Tea Party yahoos were blathering about the need for fiscal austerity.

FWIW, I happen to think the best intermediate macro text is by Wendy Carlin and David Soskice, “Macroeconomics: Institutions, Instability, and the Financial System.” I prefer their version of the workhorse 3-equation model to David Romer’s.

As Trump promised 2nd quarter achieved 3% GDP. Let’s understand that the 1st quarter 1.2% was a lag from the Obama administration policies before the Trump policies could get implemented. To be sure, a one quarter expansion is not unique, but the remainder of 2017 is expected to continue at this pace (or higher).

Policy asymmetry or less ignorant policy?

exactly what policy change caused 2nd Q GDP reach 3%.

I confess, I have not thought it would be difficult to reach 3% growth since over the past 4 years when real GDP growth was only 2.1%, real non-farm output growth averaged 2.75% — see the productivity reports . So all rump had to do to get 3% growth was allow government to grow.

But I still want to hear what Trump actually did to cause growth to improve.

Spencer, how many regulation reductions do you want me to list? I know being pr0 versus anti business does not matter to a great many, but that attitude change has also made a difference. Are you just being disputatious or seriously missing the difference(s)?

GDP grew faster than 3% in 8 quarters from 2009 to 2016. “Let’s understand” that your point is entirely irrelevant. Oddly, I don’t see you mentioning today’s weak job numbers.

Some people really need to grow up.

CoRev Did you also notice that there were 8 quarters during the Obama years that the economy grew at an annual rate of 3% or more? Why is it that you’re so quick to see significant trends based on one observation in this context, but you totally dismiss many, many observations of higher temperature trends in another context?

And yes, I would like you to list the Trump policy changes that are supposedly responsible for the 3% growth rate. And please show your math in terms of standard growth accounting terms.

There are some warning signs ahead. Light truck sales have slumped. New housing starts have slumped. Employment numbers have been disappointing, as have labor force participation numbers. Yields on export crops are lower than expected due to drought conditions. The stock markets seem to have run out of steam the last month. And now a hurricane wipes out hundreds of billions in capital investment and housing.

2slugs and Mike V, the NYT https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/30/business/economy/gdp.html said this: “Most economists are expecting the economy to expand at a rate of roughly 3 percent in the second half of 2017.” And nearly every article noted this was the highest rate in 2 years.

It’s quite the reach to point to monthly highs when comparing quarterly growth. Quite desperate and juvenile. If the “most economists” estimate is true, then Trump’s 1st calendar year will be a higher average than any of … you know who.

2slugbaits, that’s the most ridiculous assessment of those economists I’ve ever heard. For example, Barro in 2009 predicted the spending multiplier is lower than expected. His assumptions matched the subsequent data very well. The economists you criticized have an excellent understanding of the macroeconomy.

https://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/federal-spending-killing-economy-government-stimulus

PeakTrader Citing a Forbes article with a Cato link should have been your first clue that the column was pure BS and factually challenged. First, the Barro study cited in the article was deeply flawed, as many economists have pointed out ad nauseam. Have you read the Barro paper? I have. It’s stupid…and as I said, the only thing it proves is that Barro does not understand how fiscal policy actually works and that he gets the lags completely wrong. Second, the economists at the IMF and OECD has studied the fiscal multipliers during the Great Recession and found them to be quite robust when the economy is in a deep slump and at the ZLB. The multipliers are in the 1.5 neighborhood. And this applies across many countries. No one doubts that the fiscal multiplier is less than 1.00 when the economy is in the recovery phase and not at the ZLB. The problem with the economists you cited is that they believe the fiscal multiplier is always the same irrespective of the state of the economy…which is what happens when you believe markets are always in equilibrium. Barro, et al. best days are behind them. When I read their papers it takes me back to the days of shoulder pads, stadium rock and blow dried hair. And their papers have aged about as well.

I don’t know if you actually read the A-G paper that Menzie cited, but their main point can be summarized in the old adage “different horses for different courses.” The effectiveness of fiscal multipliers depends on the state of the economy; i.e., it is condition-based. I have some quibbles with the A-G paper (e.g., I’m not crazy about they way the estimated trend growth, I think they mostly ignored the role of exchange rates, etc.), but in their defense they did admit upfront that they wanted to sweep all that stuff into atheoretical real world empirical stuff.

2slugbaits, right, if it’s not a liberal link, it must be “BS.”

Personally, I am a fan of conservative Keynesian counter-cyclical policy. Allow automatic fiscal stabilizers to do their thing. Avoid the temptation of discrete fiscal measures that are too often designed more for political effect than the intended effect.

In this dream world, monetary policy minus the employment mandate does the heavy counter-cyclical lifting. In this dream world, targeted fiscal policy works on structural unemployment at all phases of macroeconomic fluctuations.

The U.S. consumption boom of the 2000s, which caused annual U.S. trade deficits to reach 6% of GDP, while real U.S. GDP grew at 3%, shifted dollars from U.S. consumers to foreigners, who bought U.S. Treasury bonds. U.S. budget deficits shrunk falling to $162 billion in 2007. However, the massive dollar shift implied the federal government was still spending too much and failed to refund those dollars to consumers in the form of tax cuts. So, a large tax cut was needed in the recession (I suggested $5,000 per worker or $700 billion, along with a substantial increase, rather than extensions, in unemployment benefits, and a permanent tax cut) to produce a real recovery.

“Conceptually, full employment is when factors of production are utilized at a rate such that inflation does not accelerate.”

This definition is problematic. We have had non-accelerating inflation for the last 10 years. That certainly doesn’t mean we have had full employment.

Since it is Fed policy to never let inflation exceed 2%, we can never know if we have full employment.

CoRev It’s quite the reach to point to monthly highs when comparing quarterly growth.

Huh? Monthly highs??? I said that there were 8 quarters (i.e., one-fourth of the time) that the annual (real) growth rate was at least 3%. We’ll see about that sustained 3% growth rate for the balance of the year.

PeakTrader However, the massive dollar shift implied the federal government was still spending too much and failed to refund those dollars to consumers in the form of tax cuts.

Let me refresh your memory. Bush #43 gave us large tax cuts in 2001 and again in 2003. Those tax cuts along with two wars played a big role in turning budget surpluses into budget deficits. Those tax cuts coupled with lax regulations that encouraged people to borrow against equity reduced the rate of personal savings from disposable income. Any decent macro text will tell you that increasing those twin deficits in private sector saving as well as government sector savings will result in a triple deficit in the current account. Tax cuts reduce national saving (i.e., the sum of private and government saving). The Bush’s fiscal polcies coupled with lax financial regulations went a long way towards a deteriorating trade imbalance with China.

2slugbaits, it should be noted, much of that budget surplus should’ve been used to minimize the 2001 recession, which in itself caused a substantial drop in tax revenue and more spending on the unemployed. Fortunately, Bush’s timely tax cut contributed to a very shallow recession. Also, a major demographic shift began or reversed after 2000. Moreover, there was a massive creative-destruction process, mostly in 2000-02. The Bush Administration tried to regulate Fannie and Freddie in 2004, but was opposed by Congress. Since Congress opposed slowly tightening lending standards through regulations, a $700 billion annual tax cut in an $800 billion annual trade deficit would’ve allowed the spending to go on, along with strengthening household and bank balance sheets, which deteriorated badly, because of a selfish Washington.

The 2001 Bush tax cut was signed into law on 7 June 2001. According to NBER the recession ended five months later in November 2001. So you’re trying to tell us that Bush’s fiscal policy completely reversed the recession with only a five month lag. You betcha. I’ve never heard of any economist who would sign up to fiscal policy kicking in after only 5 months. I think you’d be on safer grounds if you said that in Dec 2000/Jan 2001 the Fed recognized that a recession was imminent and made several quick interest rate cuts. That’s at least consistent with commonly accepted monetary lags.

As to Fannie and Freddie, their actions certainly didn’t help, but by 2004 the horse had long since left the barn. Fannie and Freddie were late arrivals to the party. I suggest you look at mortgage originators like Countrywide, slime ball bankers and corrupt ratings agencies. And oh by the way, Congress was controlled by the GOP through the first six years of the Bush Administration. Remember?

I didn’t have problems with Bush using some of the surplus to soften the drop in aggregate demand during the 2001 recession. The tax rebates helped people at the bottom of the income ladder. But the tax cuts for the rich were poorly designed and unhinged from fiscal reality. Remember how Cato (you know…the think tank you like to cite) even promised that the tax cuts would pay for themselves and result in huge budget surpluses by 2011. Remember that?

It was a short and shallow recession. I guess, you never heard of expectations. And, you want people to believe Democrats were nowhere to be found, in their role creating the financial bubble.

http://bubblemeter.blogspot.com/2008/10/barney-frank-and-christopher-dodd.html?m=1

Peak, I’ve had the same discussion here with 2slugs and others during Bush’s administration. He was just as blind then, even with the history happening.

President George W. Bush: Total = $3.293 trillion, a 57 percent increase.

FY 2009 – $1.16 trillion. ($1.413 trillion minus $253 billion from Obama’s Stimulus Act)

FY 2008 – $459 billion.

FY 2007 – $161 billion.

FY 2006 – $248 billion.

FY 2005 – $318 billion.

FY 2004 – $413 billion.

FY 2003 – $378 billion.

FY 2002 – $158 billion.

He hasn’t changed much: ” Remember how Cato (you know…the think tank you like to cite) even promised that the tax cuts would pay for themselves and result in huge budget surpluses by 2011.” Even in light of the deficit evidence:

2005 -$95

2006 – $70

2007 -$87 With little imagination and without the bad luck of another recession a deficit projection would have resulted in CATO’s estimate. From here: https://www.thebalance.com/deficit-by-president-what-budget-deficits-hide-3306151

2008 -$77

2009 +$7

2010 +$84

2011 +$84

At that time I was helping review Mike Kimel’s book “Presimetrics” which tried to show economic impacts of presidential administrations without seriously delving into impacts of policies.

2slugs and others could not accept there was any positive to Republican policies, but the past 8 years has shown the opposite is true. Accordingly we see these kinds of caveats: “We’ll see about that sustained 3% growth rate for the balance of the year. ” and “Remember how Cato (you know…the think tank you like to cite) even promised that the tax cuts would pay for themselves and result in huge budget surpluses by 2011.”

It must be really hard to admit you’re wrong if you are a liberal. At least I have never seen 2slugs do so, even when he has been laughingly wrong.