From a paper by Michele Andreolli, Natalie S. Rickard, and Paolo Surico (presented at NBER Summer Institute Monetary Economics sessions):

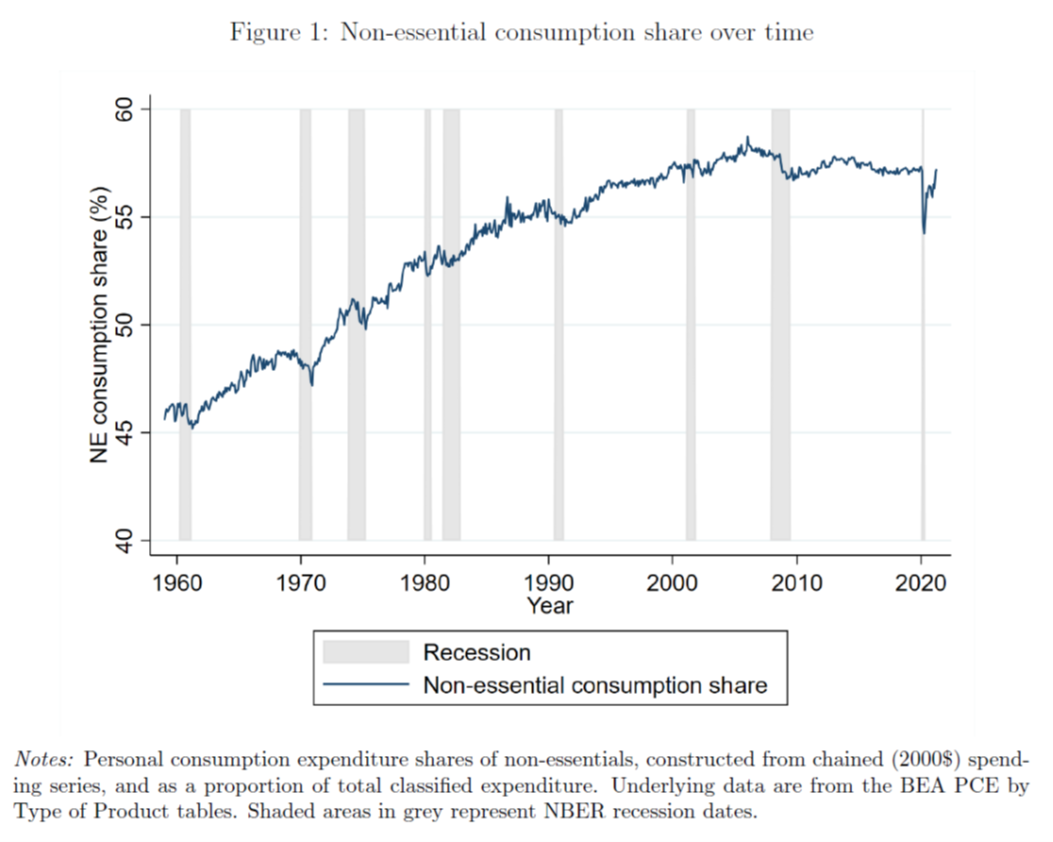

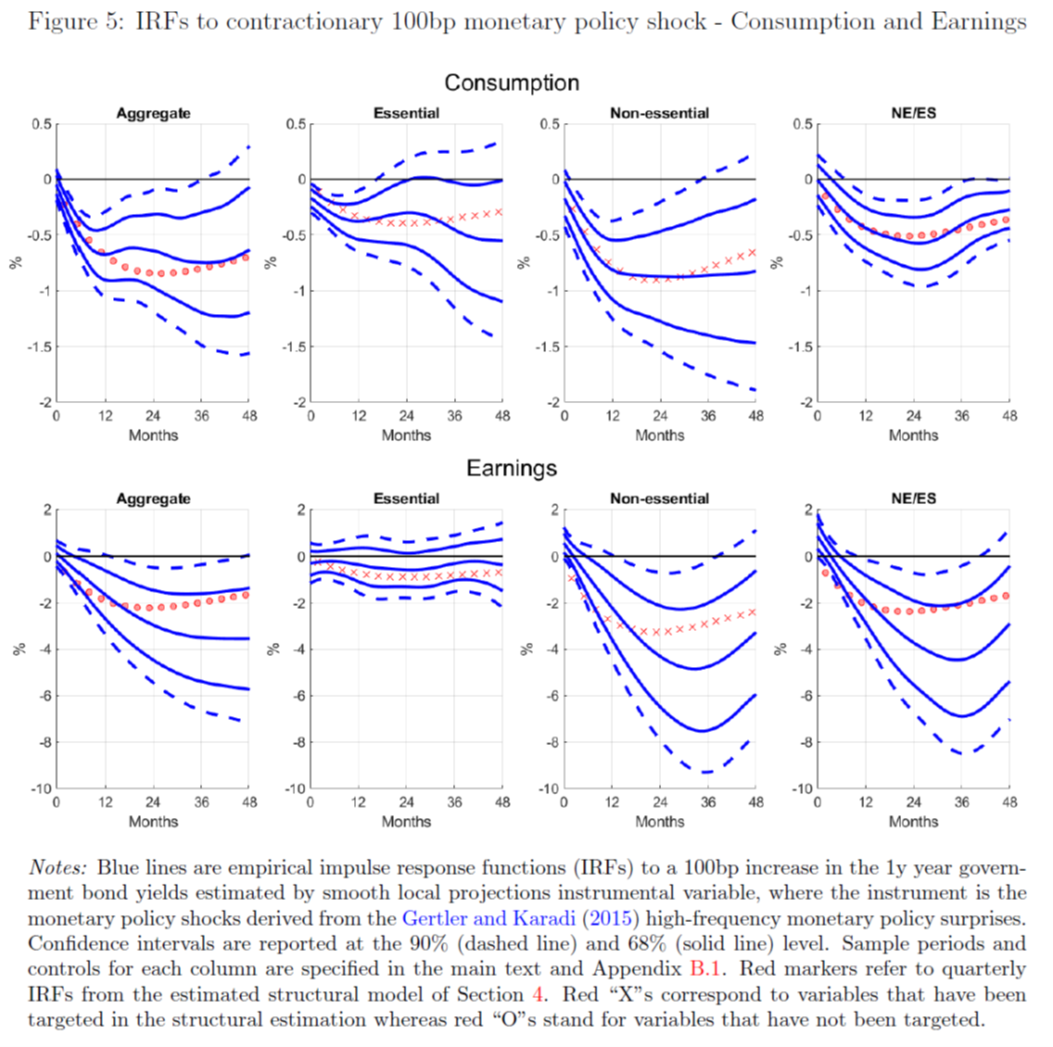

Using newly constructed time series of consumption, prices and earnings in essential and non-essential sectors, we document three main empirical regularities on post-WWII U.S. data: (i) spending on non-essentials is more sensitive to the business-cycle than spending on essentials; (ii) earnings in non-essential sectors are more cyclical than in essential sectors; (iii) low-earners are more likely to work in non-essential industries. We develop and estimate a structural model with non-homothetic preferences over two expenditure goods, hand-to-mouth consumers and heterogeneity in labour productivity that is consistent with these findings. We use the model to revisit the transmission of monetary policy and find that the interaction of cyclical product demand composition and cyclical labour demand composition greatly amplifies business-cycle fluctuations.

Here are two key pictures.

Source: Andreolli et al (2024).

Note that the non-essential share was decreasing before the pandemic (even as consumption overall was rising). Impulse responses functions for a 100 bp monetary shock show that disaggregation is important in seeing what portions of consumption (and hence the aggregate economy) respond.

Source: Andreolli et al (2024).

What’s a non-essential? The authors define items with demand elasticities greater than one (in absolute value) as non-essential. Some obvious items: food away from home, entertainment, public transit.

The implication: Non-essentials respond much more strongly the contractionary monetary policy than do essentials. That means catching early the contractionary effects of monetary policy requires looking at consumption at a disaggregate level, and preferably at higher frequency than the usual monthly series. What do these indicators look like?

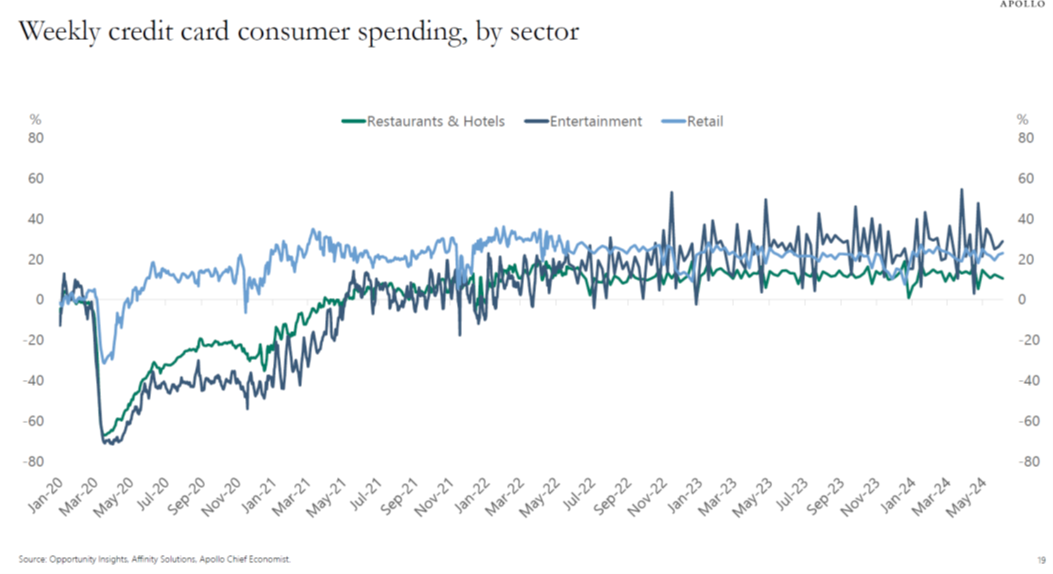

Here’s credit card expenditure growth, courtesy of Torsten Slok et al. Restaurants and hotels (proxy for pleasure travel) and entertainment are still growing, even keeping in mind inflation.

Source: Slok, Shah, Galwankar, “Daily and weekly indicators for the US economy,” Apollo, 17 August 2024.

From Slok’s communication today, regarding these non-essential higher frequency indicators:

Looking at the latest daily and weekly data shows that … restaurant bookings are strong, air travel is strong, hotel occupancy rates are high, … and Broadway show attendance and box office grosses are strong. …The bottom line is that there are no signs of a recession in the incoming data…

This is contra Michaillat-Saez based on monthly data through July, discussed in this post, as well as individuals in this list.

I have to confess a decent amount of surprise that consumption hasn’t dropped more. I still expect it to drop between now and end-2024.

“… (i) spending on non-essentials is more sensitive to the business-cycle than spending on essentials; (ii) earnings in non-essential sectors are more cyclical than in essential sectors; (iii) low-earners are more likely to work in non-essential industries.”

(i) Knew that.

(ii) Knew that.

(iii) Should have put that together, but hadn’t.

The fact that the first two are more or less self-evident isn’t a fault in the research. Demonstrating that the data agree, or not, with casual observation is part of science.

The further conclusion that high variability in demand for non-essentials and in employment in non-essential industries exacerbates business-cycle swings is also what one would expect, but good to see verified in the data.

So, we have a common-sense coincident indicator of recession? Or a leading indicator?

The fact that some employment data and some financial data show recession while output and other employment series don’t show recession has become part of the economic landscape. Same for consumer moods disagreeing with the majority of economic data. The next generation of grad students will have no shortage or research topics.

Suppose there is Perfect Leading Indicator A, which always peaks 12 months before a recession and bottoms 3 months before a recovery begins; and Perfect Coincident Indicator B, which always peaks the month a recession begins and bottoms the month it ends.

Since by its own terms of exposition – measuring declines in spending *during* a recession – this paper picks up *all* of the decline in indicator B, but only some of the decline (and theoretically possibly no decline at all!) in indicator A.

I suspect if we took all of the spending categories ranked by the authors and measured each of them from their individual peaks to troughs, the result might be somewhat different, i.e., in general that the biggest ticket items (housing, vehicles) suffer the most, the least expensive purchases the least.

Although the Conclusion to this paper begins “What drives business-cycle fluctuations?” the more accurate description is the first line of the introduction, “A central question in macroeconomics is how business-cycle shocks propagate to the real economy.”

That’s because the authors divide “essentials” from “non-essentials” based on how much spending fluctuates *during* a recession, I.e., once it has begun. By that time, “what drives” the cycle has already occurred.

The Conclusion appears on much more solid ground when it states:

“The main idea is that … the consumption of the rich drives the income of the poor. In the face of economic adversities, non-essential purchases are easier to postpone and their contraction is dominated by the behaviour of affluent households. The latter has a particularly large effect on low-income families, whose workers are more likely to be employed in non-essential industries, and thus their labour demand suffers more from the drop in product demand….”

Note from the above that, by its own terms, the “economic adversities” have already occurred before the effect kicks in.

So while we want to look at things like restaurant reservations as coincident and confirmatory indicators of a recession, we still need to look at things like housing, vehicle, and other durable goods purchases in advance thereof.

I would say that this way: A precipitator of recessions is unlikely to be a good predictor of a recession. If there are 5 different things that can precipitate a recession they will for the first step or two be different and only later in the process meet in things like reduced consumptions, reduced employments, reduced interest rates, inverted yield curves etc. etc., that are all indicative of a stalled/falling/unhealthy economy. Whether that stalled/falling economy will get bad enough to make some arbitrary threshold of two quarters of negative GDP + (whatever), is hard to say if those indicators show weakish signals. If all the indicators are on “red alert” then we are indeed in or close to a recession. That gets back to my pet peeve of taking a continuous parameter [Delta GDP] and trying to make it a categorical parameter [Yes, No recession] when that process simply lose information – which people then try to recover with semiquantitative terms such as week, mild, bad, severe, etc.

The notion that household debt-driven consumption drives recessions fits here nicely. The poor, even if indebted, don’t represent a very large share of household debt. It’s the on-again, off-again pattern of borrowing and spending among better-off households which makes debt-driven consumption important. And the variable increment is non-essential, as defined by the authors.

Great post by Menzie, and well said comment by MD.

This is why readers drop by here.