“For many, many years, the United States has suffered through massive trade deficits. That’s why we have $20 trillion in debt. So we’ll be changing that.”

This statement was made during the meeting with the South Korean President on June 30th [1]

“For many, many years, the United States has suffered through massive trade deficits. That’s why we have $20 trillion in debt. So we’ll be changing that.”

This statement was made during the meeting with the South Korean President on June 30th [1]

How much does the U.S. government owe? The number that is subject to the recurrent debt-ceiling wrangling includes intra-government debts that the Treasury is imputed to owe to other Federal government operations. For example, Social Security taxes have historically exceeded benefits paid out. The surplus was used to pay for other government programs, and the Social Security Trust Fund was credited with corresponding holdings of U.S. Treasury securities representing the accumulated value of those surpluses. Many of us think of this as an I.O.U. that the government issued to itself. Economists usually subtract those intra-government debts when talking about the size of the federal debt, relying instead on the Treasury’s measure of debt held by the public. Although many of us have made use of the latter numbers in academic research, policy analysis, and lectures to our students, those data are also getting less reliable in recent years.

Continue reading

President Trump is upset that the media missed this economic event:

“The media has not reported that the National Debt in my first month went down by $12 billion vs a $200 billion increase in Obama first mo”

From the article:

Officials said the raids targeted known criminals, but they also netted some immigrants without criminal records, an apparent departure from similar enforcement waves during the Obama administration. Last month, Trump substantially broadened the scope of who the Department of Homeland Security can target to include those with minor offenses or no convictions at all.

In an EconoFact post from Saturday, Michael Klein and I noted that usually for the US, the trade deficit grows during times of robust economic growth.

Elevated real interest rates and policy uncertainty explain a dollar about 4% higher than election day.

We have had previous experience with episodes of tax cuts unmatched by spending reductions, in terms of the impact on external balances. Below I plot the evolution of the Reagan twin deficits, and the evolution of the G.W. Bush twin deficits.

Last week I puzzled over the response of financial markets to the U.S. election. Since the election, the S&P500 is now up 3%, the dollar is up 4.6% against the euro, and most remarkable of all, the 10-year Treasury rate has gone up 50 basis points. Here I offer some further thoughts on the last development.

Continue reading

I was astounded not only by the outcome of the U.S. presidential election but also by the response of financial markets.

Continue reading

That’s the title of an informal panel at the UW La Follette School of Public Affairs on Tuesday. Here are the slides that underpin my presentation.

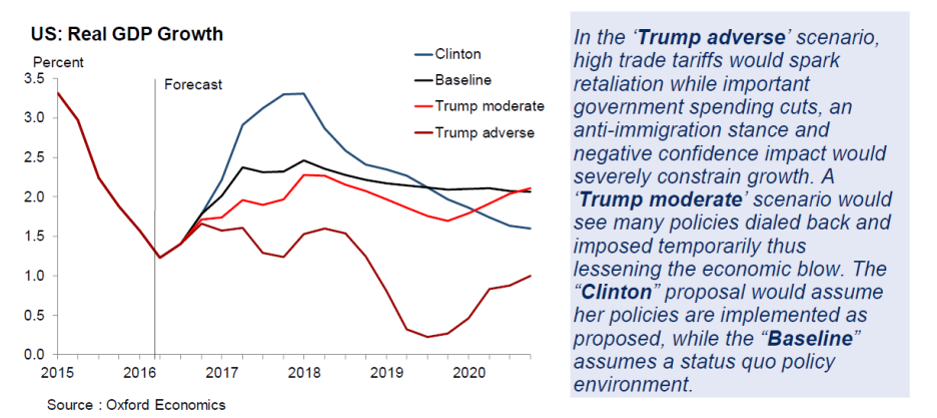

For now, let the following figure summarize the choices.

Source: “Trump vs Clinton: Polarization & uncertainty,” Research Briefing (Oxford Economics, 19 Sept. 2016) [not online].

The other panelists are Pam Herd, Greg Nemet, Rourke O’Brien, and Tim Smeeding.