In a recent article, Amity Shlaes asserts official statistics mismeasure how we experience inflation. I’m going to agree, but not for the reasons you might think. It’s not because John Williams’ Shadowstats, which she appeals to, is right (Jim has comprehensively documented why each and every person who cites that source should be drummed out of the society of economists or aspiring economic commentators). Rather it’s because I think people do have biases — i.e., the steady-state rational expectations hypothesis might not be applicable.

Ms. Shlaes writes in “Inflation Vacation”:

…The price zap is an inflation zap. The reason you thought you could afford this vacation in the first place was that you know a little about money. All the official numbers, especially the Consumer Price Index, say that inflation is reasonable. Economists you respect tell you the wages are low because of “misallocation of resources.” Janet Yellen, the new Fed chairman, says she’s not worried. Maybe she will have a good vacation.

But other numbers suggest that inflation is higher than what the official data suggest. One set, from which some of the price bites above were taken, is here. For a more thorough review of why official numbers err, have a look at the work of John Williams, a consultant who has tracked data over the years.

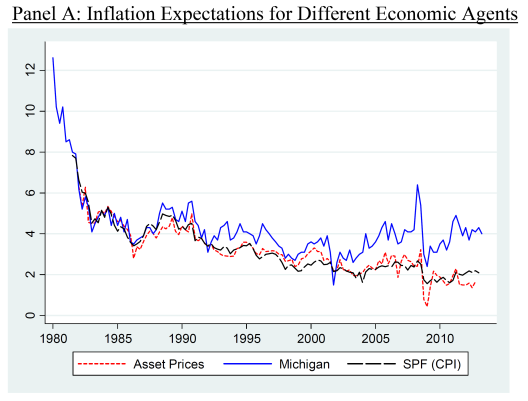

It’s at this point that I believe the findings by Coibion and Gorodnichenko (2013), discussed earlier by Jim, is of interest. They note that households hold noticeably different expectations regarding inflation than do professional forecasters, or markets; in this sense, household expectations are “unanchored” to the extent that they are consistently higher than ex post realizations of inflation.

Source: Figure 6, Panel A, Coibion and Gorodnichenko.

Why does this pattern arise? From the paper:

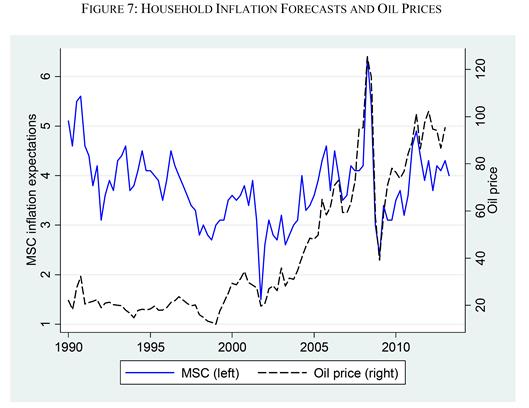

…why did households hold such different beliefs than professional forecasters? Our suggested answer can be seen in … Figure 7. Household inflation forecasts have tracked the price of oil extremely closely since the early 2000s, with almost all of the short-run volatility in inflation forecasts corresponding to short-run changes in the level of oil prices. From January 2000 to March 2013, for example, the correlation between the two series was 0.74. In contrast, the correlation between SPF inflation forecast and oil price over the same period was -0.12. The strong sensitivity of consumers’ inflation expectations to oil price has historically been strong: the correlation between MSC inflation expectations and real oil price over 1960-2000 was 0.67.

Source: Figure 7, from Coibion and Gorodnichenko.

Households that tend to have more gasoline expenditures tend to be more sensitive to oil prices. This further buttresses the view that expectations differ from professional forecasters, and market based measures which are unbiased. See more on the characteristics of household surveys by R. Waldmann/Angry Bear.

On another count, Ms. Shlaes discounts both hedonics and price index theory:

The Bureau of Labor Statistics or the Fed also argued that the quality of some items (camera, movie) had improved over the years. The technology it took to make X-Men: Days of Future Past is leagues ahead of the technology used for Gladiator. The movie theater itself has better seats. Therefore, the ticket price should be higher. The economists at the BLS say they discount for that: “The hedonic quality adjustment method removes any price differential attributed to change in quality,” they write. But perhaps they use such indexes to hide true price increases.

And:

Decades ago, authorities pointed out that people substitute a cheaper item when what they originally bought was too expensive. They altered the index to capture substitution. If steak is expensive, you buy chicken. The result of their fiddle is that inflation looks lower than it would otherwise. That’s disappointing. No vacation is a true vacation without a really good tenderloin.

On the first point — hedonics — it’s telling that movies were mentioned, but not telecommunications. From my standpoint, I can say there has been a big de increase in what my smartphone can do relative to my first mobile phone in 2000.

On the second point, this observation is funny because the CPI is a quasi-Laspeyres index (see this post), so it tends to minimize (although not completely eliminate) the effect she speaks of. Now, it’s true that the index weights are updated each two years, but even then, those with an acquaintance of price index theory understand that in the absence of the true underlying utility function of consumers, measuring the “true” rate of inflation is infeasible, and the Laspeyres index tends to over-state the rate of inflation (the chained CPI inflation rate tends to be lower than that obtained using the standard quasi-Laspeyres CPI [1]).

Actually, I suspect that the reported inflation rate actually understates the inflation relevant to Ms. Shlaes, if her household is in the upper 25% income decile. That’s because the CPI weights are appropriate to a household at the 75% income decile (see this post on plutocratic vs. democratic price indices). Those at lower income levels are likely facing a higher inflation rate than she does.

One point where I do disagree vociferously with Ms. Shlaes assessment is here, where she discusses the Liesman-Santelli exchange (discussed in this post):

If you study the last part of the video, where the CNBC host gets bullied into silence by Steve Liesman, you’ll see the problem. The price today for talking about inflation is itself too high.

Lots of people have been discussing inflation and hyper-inflation for the past six years. I don’t think the costs are that high at all. And in fact I expect to hear more inflation worries, day after day.

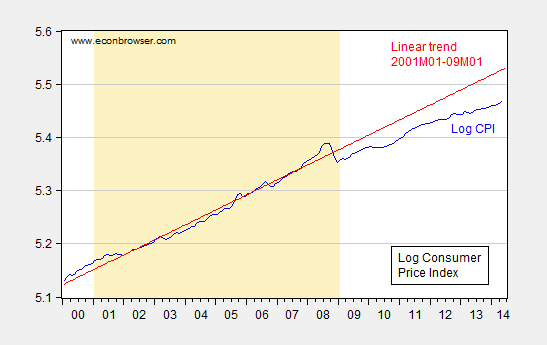

Final point: to the extent that the CPI growth has changed over time, it is interesting to consider the price level counterfactual implied by the inflation rate over the 2001M01-2009M01 period. This is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Log CPI (blue) and linear trend estimated over 2001M01-09M01 period (red). Sample period for estimation of trend shaded tan. Source: BLS (May 2014 release) via FRED and author’s calculations.

It certainly looks to me that inflation is lower (i.e., the slope is flatter) post 2008 than before. Biases that existed in the past regarding “zaps” exist now. Indeed, if anything one bias that existed before — due to imputation of owner occupied rent — is probably resulting in an overstatement of inflation right now [2]

Update, 7/24 3PM Pacific: Lars Jonung points out that he in earlier work found serial correlation in forecast errors from surveys of consumers, and further conjectures that the costs of acquiring data might be the source of the lack of unbiasedness. See Jonung (1981) and Jonung and Laidler (1988). This point is consistent with my statement that the forecast errors from the Michigan survey failed to exhibit behavior consistent with the “steady-state rational expectations hypothesis”. This doesn’t mean the behavior is necessarily irrational; it could be the learning process is slow enough in response to new shocks that errors are serially correlated (near rationality a la Akerlof and Yellen for instance).

It’s an interesting question: people repeatedly misestimate inflation.

As a bunch of work demonstrates, people are pretty darned bad at estimating many things. It isn’t just innumeracy but the way we’re constructed builds in these leaps to wrong conclusions.

I think a comparison might be made to baseball. Statistical analysis has actually validated much traditional wisdom. One that pops to mind is stealing 3rd: turns out the old rule of thumb fits what should be done if you examine all the outcomes. Why? I mean why is that rule of thumb so good? The answer is pretty obvious: the game is played with a simple set of comprehensible rules over and over and over. Think of any rule of thumb, like ones for carpentry: developed over many repetitions within a narrow set of rules.

Now apply that to inflation. You can’t, unless you’re estimating costs for a very large business – and remember farmers these days use prediction software that ties in to rain estimates, etc. to generate expected yields (and thus prices) and amounts of fertilizer, weeding, etc. that must be done. But for me? For people living their lives? Estimating inflation is one of those things we get wrong because there is no set of comprehensible rules that regularly repeat. Instead we’re faced with myriad circumstances and changing needs and huge varieties of potential substations – some “better” and maybe more expensive (or less though better) and some not – and we pursue choices for another multitude of reasons. It isn’t there’s a runner on 2nd with 1 out and the choice is run or not.

Generally when people speak of inflation, they are really speaking of real income. High unemployment has made income increases difficult so inflation is more felt.

“High unemployment has made income increases difficult so inflation is more felt.”

It depends if you have savings or not. If you have savings you can use some of your savings to compensate or save less. People without savings don’t have that ability and might go into debt. The people who watch Fox News are extremely old and have savings. They’ve been convinced inflation is higher than it actually is and change their behavior as a result.

The Fed has been trying to raise inflation to raise nominal growth (inflation and real growth) to raise real growth.

Unfortunately, the Fed hasn’t been getting much help from fiscal policy and policies out of Washington.

****

January 2007

Bloomberg’s Tom Keene: “…As you know, I’m a big fan of nominal GDP – this, folks, is real GDP plus inflation. It’s the ‘animal spirits’ that’s out there. You say be careful, Bill Gross. It looks real good to me, Bill. I see 6% year-over-year nominal. You say that’s going to end?”

Pimco’s Bill Gross: “…Ultimately, the inflation component affects the real growth component. To the extent that you have nominal GDP – in my forecast 3 to 3.5%, that’s really not enough growth in terms of the economy itself to support asset prices at existing levels. And so, declining assets prices ultimately factor into eventually lower real growth. But that’s not for mid-2007 but perhaps for later in the year.”

Tom Keene: “When we look at six months of low nominal GDP, is that enough to link directly into the ‘animal spirits” of the business investment component of GDP – the “animal spirits” of business men and women?”

Bill Gross: “Well sure it is. When you realize that the average cost of debt in the bond market – and therefore in the economy and this includes mortgages – it is about 5.5%. If you can only grow your wealth and service that debt at 3.5% rate, then that has serious implications.

When you go back to 1965, Merrill [Lynch] did this study – in terms of asset prices during periods of time when nominal growth grew less than 4%. Risk assets have been negative in terms of their appreciation and actually bonds have done pretty well.

The question becomes why hasn’t that happened yet, and I think we’re simply in a period of time where there are leads and lags that are much like the leads and lags of Federal Reserve policy.”

****

Here’s what Bob Brinker said about the Fed (Dec 2012):

“It’s only because the Federal Reserve has been active that we have any growth at all in the economy….The Federal Reserve is the only operation in Washington doing its job.

The only person that would criticize Ben Bernanke would be a person who is so clueless about monetary policy and (the) role of the Federal Reserve as to have nothing better than the lowest possible education on the subject of economics….Anybody going after Ben Bernanke is a certified, documented fool….”

You left out the part about Amity being a bought-and paid-for pseudo-economist who routinely says things that her masters want said. For instance, when she wrote that the economic recovery programs of the mid-1930s didn’t increase employment, because jobs created by the recovery programs don’t count. If you leave that part out, you have left out important information about Amity for any reader not familiar with her work.

Menzie,

I love your post because it is so instructive in how economists love to talk of angels dancing on the head of a pin.

“…official statistics mismeasure how we experience inflation. I’m going to agree…”

This was a startling admission. I had to look back to make sure this was actually written by you. I have never heard you make such and admission.

“…households hold noticeably different expectations regarding inflation than do professional forecasters, or markets; in this sense, household expectations are “unanchored” to the extent that they are consistently higher than ex post realizations of inflation.”

But this is back to the old Menzie. The housewife who has to balance a budget is just too stupid to understand that her food bill is actually not increasing. She needs an expert to explain it to her.

“Households that tend to have more gasoline expenditures tend to be more sensitive to oil prices.”

Duh, you think? How can you conplain about price rises in a commodity that you spend a large part of your budget on. The experts know that you shouldn’t drive so much so they will discount the weight of spending on gasoline. Come on; get with the program.

“This further buttresses the view that expectations differ from professional forecasters, and market based measures which are unbiased.’

Thank goodness for professional forecasters. Without them we would think that our food budget is shrinking in purchasing power. They have to wisdom to straighten us out. Just put another hole in your belt.

“On the first point — hedonics — it’s telling that movies were mentioned, but not telecommunications.

So the experts can determine the hedonics of telecommunications much better than the average person. Don’t you know that when judging price increases the ability of your cell phone to play computer games and measure your weight are much more important than going to the movies. And the experts are always right in their judgment of the hedonics of a good. How do I know? Because the experts tell me so.

…it’s true that the index weights are updated each two years, but even then, those with an acquaintance of price index theory understand that in the absence of the true underlying utility function of consumers, measuring the “true” rate of inflation is infeasible, and the Laspeyres index tends to over-state the rate of inflation (the chained CPI inflation rate tends to be lower than that obtained using the standard quasi-Laspeyres CPI”

Once again a startling admission. An index is totally invalid within 2 years but then isn’t it becoming invalid over the period of the 2 years? Why isn’ t the index updated yearly, or monthly, or daily? And even the the index “tends to over-state the rate of inflation.” Then what is the purpose? And how do you know it over-states inflation if your index is not a valid measure of inflation. How do you know the price increases are too high or too low or just right? The experts tell us, of course.

“Lots of people have been discussing inflation and hyper-inflation for the past six years. I don’t think the costs are that high at all.”

It is true that lots of people have been discussing inflation for many years, but the question is have their critics been more reasonabel or more hostile. Here we have an entier post offering a tangential criticism of one of those people discussing inflation. While many decibels softer than the Liesman-Santelli exchange the implication is clear; Shlaes shows her ignorance because he has the temerity to question the experts.

“It certainly looks to me that inflation is lower (i.e., the slope is flatter) post 2008 than before.

So with all of the errors in inflation being pointed out let’s just choose one and graph it. See, I told you inflation is below expectations, not the housewife’s expectations you silly, the experts expectations. What do you mean prices should be expected to decline in the bust phase of the business cycle? Are you saying that prices can actually decline when money is pumped into the economy? Don’t you believe in the Quantity Theory of Money? You mean you believe that a credit crisis can actually drive prices down but drive income and production down even more? What are you, an Austrian economist or something?

Ricardo,

You are usually a Cornucopia of Error. But this time you outdo yourself. I spend some time refuting them, but as I am pressed for time today, I’ll just await the next installment.

ricardo,

why do you even view this blog if your sole purpose is to constantly contradict menzie? if menzie said the grass was green, what color would you demand it to be? create your own blog so you can debate with its sole visitor.

I like Robert Waldmann’s thesis that Shadowstats, Shlaes, Santelli and Fox News, etc. are raising inflation expectation of those who live in that bubble and thereby helping out the Fed and Obama.

HUMAN ACTION by Ludwig von Mises

XVII. INDIRECT EXCHANGE

6. Cash-Induced and Goods-Induced Changes in Purchasing Power

The notions of inflation and deflation are not praxeological concepts. They were not created by economists, but by the mundane speech of the public and of politicians.

The semantic revolution which is one of the characteristic features of our day has also changed the traditional connotation of the terms inflation and deflation. What many people today call inflation or deflation is no longer the great increase or decrease in the supply of money, but its inexorable consequences, the general tendency toward a rise or a fall in commodity prices and wage rates. This innovation is by no means harmless. It plays an important role in fomenting the popular tendencies toward inflationism.

First of all there is no longer any term available to signify what inflation used to signify. It is impossible to fight a policy which you cannot name. Statesmen and writers no longer have the opportunity of resorting to a terminology accepted and understood by the public when they want to question the expediency of issuing huge amounts of additional money. They must enter into a detailed analysis and description of this policy with full particulars and minute accounts whenever they want to refer to it, and they must repeat this bothersome procedure in every sentence in which they deal with the subject. As this policy has no name, it becomes self-understood and a matter of fact. It goes on luxuriantly.

The second mischief is that those engaged in futile and hopeless attempts to fight the inevitable consequences of inflation–the rise in prices–are disguising their endeavors as a fight against inflation. While merely fighting symptoms, they pretend to fight the root causes of the evil. Because they do not comprehend the causal relation between the increase in the quantity of money on the one hand and the rise in prices on the other, they practically make things worse. The best example was provided by the subsidies granted in the Second World War on the part of the governments of the United States, Canada, and Great Britain to farmers. Price ceilings reduce the supply of the commodities concerned because production involves a loss for the marginal producers. To prevent this outcome the governments granted subsidies to the farmers producing at the highest costs. These subsidies were financed out of additional increases in the quantity of money. If the consumers had had to pay higher prices for the products concerned, no further inflationary effects would have emerged. The consumers would have had to use for such surplus expenditure only money which had already been issued previously. Thus the confusion of inflation and its consequences in fact can directly bring about more inflation.

It is obvious that this new-fangled connotation of the terms inflation and deflation is utterly confusing and misleading and must be unconditionally rejected.

[It is amazing how a book written in 1940 seems to be right out of the media today.]

Really, cut and paste Von Mises?

If you are going to start the “increased money supply is inflation, and not general price increases” argument, then I will abandon you to argue with others in the seemingly private language of the Austrians where “things are what we say they are, and don’t bother us with empirical evidence when theory is enough”.

Thank you for providing such a clear example of question-begging by von Mises. The use of the word “inflation” to mean a general rise in prices, rather than a general rise in the money supply is “by no means harmless” because “It plays an important role in fomenting the popular tendencies toward inflationism.” See how he built in the claim that inflation “ism” is harmful, rather than actually taking on the question of whether inflation is a problem. (It’s not clear which definition of “inflation” he fears will be the result of “inflationism”, but from context, I’d guess it’s a rise in the money supply.) Right now, there is a need for a general rise in prices, particularly in wages, so question begging in this context is a particular problem.

I also find it kind of funny that von Mises bemoans the lack of “a term” for a rise in the money supply if “inflation” is used to mean a rise in prices. In the first place, arguing against “a rise in the money supply” is entirely possible, so his claim is nonsense. In the second place, his definition of “inflation” would leave us without a “term” for a general rise in prices, which would arguably be as bad a thing as having no term for a rise in the money supply.

Ricardo, if this bit from von Mises is the sort of thing that you find convincing, well it’s no wonder your own efforts aren’t convincing. You’ve adopted a pretty lame model.

Believe it or not, CPI has accelerated q-q annualized from 1.5% in Q3-Q4 2013 to 2.6% YTD and 3.6% for Q2, reducing q-q annualized Q2 after-tax incomes/wages to ~0% for Q2.

With nominal GDP trending since 2007-08 at 2.5% and 1.7% per capita, and 0% real final sales per capita, the US cannot withstand an acceleration of price inflation beyond 1.5-2% without the risk of q-q annualized contraction of real final sales per capita.

We’re there (as are the EZ and Japan). A “new-normal recession”. Whether the political climate will permit the event being reported is another matter.

You seem to imply that the post-recession trend in nominal GDP is somehow a controlling limit, that a rise in inflation will necessarily mean a slowdown in real growth. I’m not aware of any reason that would be true, as long as there is spare productive capacity in the economy. Yes, there has been a bit more inflation lately. There are a number of reasons to see that as a good thing, including that the real fed funds rate falls as inflation rises, something we’ve needed for a long time.

Banana, what I am asserting is that Peak Oil, record debt to wages and GDP, and peak Boomer demographic drag effects have reduced the speed limit for the US to a post-2007 nominal GDP trend rate of 2.5%, real GDP of 1% or slower, and real final sales per capita of 0%. This further implies that the effective cyclical demand constraint from insufficient after-tax and -debt service profits and incomes is closer than most economists realize to resulting in stall speed for growth and increasing risk of recession.

Consequently, the value-added output of the US economy at the slower speed limit is perpetually vulnerable to various shocks, e.g., energy, weather, fiscal, and geopolitical, that the economy would have otherwise withstood when the trend rate of real final sales per capita was in the 2-2.5% range instead of less than 1% to 0%.

This once-in-history energy, debt, and demographic constraint is also occurring in the EZ and Japan, as well as eventually in China-Asia, as China experiences increasing energy and food imports to GDP, which will combine with a decline in, or reversal of, US and Japanese FDI in China, reducing China’s real GDP per capita from decelerating growth of investment, production, and exports to GDP.

Thus, the weather effect in Q1 should not be perceived as a one-off event, as weather effects, including drought, climate change (warming OR cooling), etc., will combine with Peak Oil, demographics, fiscal constraints, and geopolitical risks to the US economy and that of the world at a much slower speed limit and perpetual risk of stall speed and q-q annualized contraction hereafter.

You pulled a switch. Your first comment pretty clearly implied that nominal GDP growth has an upper limit, so that a rise in inflation lowers the potential for real GDP growth. In your second comment, you implied that the limit is on real GDP growth. I’m interested in which view you actually hold.

If somebody here would be nice,

he could collect food prices in the nearest discounter (Aldi, Lidl, low cost, you know) on the following items, for comparison to EU and to 4 and 11 years ago in the US

Lidl EU

item EU unit EUro price

Milk liter 0.69

Tomatoes kg 0.99

toast 500 g 0.55

Butter 250 g 0.99

Chicken, frozen kg 2.35

beer, simple liter 0.57

rice kg 0.85

flour kg 0.35

baguette (60 cm length) 0.65

ham, simple kg 6

coffee 500 g 2.65

noodles kg 0.98

pork kg 4.98

egg piece 0.099

cheese kg 5.73

mozarella kg 4.4

joghurt kg 0.98

no name Cola liter 0.26

O-Juice (100 %) liter 0.95

Sugar kg 0.85

Vodka liter 7.13

schocolade kg 3.9

spices kg 13.8

cigarettes pack of 19 5

gasoline liter 1.55

electricity €/kWh 0.29

cleaner every 14d ca 3 hours 36

Computer 400

ground meat kg 4.58

canned tomatoes 425 ml 0.39

canned champignon 314 ml 0.49

would be interesting to get those numbers for your places. That doesnt take more than 10 min in the store and 5 min to type it here

“From my standpoint, I can say there has been a big decrease in what my smartphone can do relative to my first mobile phone in 2000.”

Prof. Chinn,

Didn’t you mean to say that there has been a big increase in what you smartphone can do?

Bernard

Left Coast Bernard: Yes, thanks. Have fixed.

I suspect that the reported inflation rate actually understates the inflation relevant to Ms. Shlaes

Are you saying that higher income consumers experience lower rates of inflation? Did you mean to say that “the reported inflation rate actually overstates the inflation relevant to Ms. Shlaes”? In other words, the inflation rate she experiences personally is lower than the CPI?

NickG: Yes, if she is above the 75th percentile in household income. Read the reference to plutocratic vs. democratic indices.

However, don’t the top 25% buy high-end goods that are more profitable for businesses?

Are they really getting better bargains than the other 75%?

if she is above the 75th percentile

Of course, this would be impossible if labor markets are competitive and Shlaes is restricted to earning no more than her marginal product.

UW-Madison to now give different grades based on race of the student :

http://www.aei-ideas.org/2014/07/for-representational-equity-univ-of-wisconsin-madison-calls-on-professors-to-use-racial-profiling-for-assigning-grades/

Note that Asian-American students will not receive this ‘favorable’ treatment.

It would be funny to see Menzie rationalize this policy, both as a professor at the institution, as well as an Asian-American.

Darren: You really should stop taking talking points from AEI. Maybe you should read the actual document, here. Maybe you could do a word search for “grade” or “grading”, if your technical capabilities extend to searching a PDF, and tell me if you find the word (by the way, the document has a title including the word “recommendations”). There is no command-and-control order to assign grades by racial quote. It might also be useful for you to read this document, as opposed to parroting the AEI line.

Amity Shlaes wrote a bunch of horse hockey, but some of the issues she touches on are worth understanding.

The really worthwhile point that people should understand about hedonics is how subjective it is. If for example you buy a 2015 model car for 3% more than the 2014 model price, how can you distinguish the inflation rate from the real value of improvements (aka the hedonic adjustment)? Arguably the improvements might be worth more than 3%. The reality is this is guesswork. There’s no conspiracy to overstate improvements, or to understate them. It’s simply inherently subjective and arbitrary, and people should understand that about inflation data.

Also of course inflation is experienced by everybody subjectively. Each person’s inflation rate is different, depending on what they buy or want to buy. If you mostly care about traditional goods your inflation rate is higher. If you mostly care about the latest gizmos your inflation rate is lower. That’s not a reason for saying a computed average is “wrong”, but it does help explain why so many people think the average doesn’t reflect their reality.

Menzie,

No, that recent UW document does not reference grades, but wasn’t the document you referenced a continuation of the policy discussed in Inclusive Excellence, which was adopted by the Board of Regents in 2009? That document says that “Inclusive Excellence is the umbrella framework under which the UW System and its institutions will move forward in coming years to strategically address equity, diversity and inclusion beyond Plan 2008.”

If you search that document, you will indeed find that “representational equity” is defined as “Proportional participation of historically underrepresented racial ethnic groups at all levels of an institution, including high status special programs, high demand majors, and in the distribution of grades.”

Rick Stryker: (1) If it’s really the 2009 document these folks are so exercised about, then why all the hue and outcry now, five years later. Hmm. Mysterious and mysteriouser. (2) In the 2009 document that pertains to the UW system, does it say anything about command and control allocation of grades by racial group? That is, I think some of us want as a society all racial groupings to have distribution of income that is representatives, and say not have group X all be in poverty and group Y all in the top 1% (I am sure there are some exceptions, and there are a few people who believe all of group X should be mired in poverty). But I don’t think that someone who wishes that would then say we allocate jobs to achieve that goal. In fact I could imagine someone saying let’s level the playing field so that people in all groups have a chance at getting that representative income distribution.

Menzie,

I think the reason people are exercised about it now is that UW finally got around to putting out their latest diversity plan, which people think will include the 2009 guidance. The specific reason this issue is being picked up now is that Lee Hansen, retired economics professor at UW Madison, just wrote an article called Madness in Madison questioning the workability of this plan. Although its true that nothing in the plan mandates a command and control allocation of grades, Hansen argues professors at UW will naturally adopt a grade inflation policy to avoid accusations of inequitable grade distributions. The headline of the AEI article is a distortion of the UW policy and if you just read the headline you’d get a false view; however, AEI does make clear what Hansen’s actual argument is later on by quoting him.

stryker

“Proportional participation of historically underrepresented racial ethnic groups at all levels of an institution, including high status special programs, high demand majors, and in the distribution of grades.”

a statement like this says nothing to university professors regarding the imposition of grading standards based on race. it acknowledges they should be aware of any differences between underrepresented groups, and if differences are found it is the responsibility of the university as a whole to understand why these differences exist. but it in no way mandates a professor to distribute grades in a particular way based on race. i don’t think there is a constituent faculty in the country who would allow such a policy to be implemented.

“The headline of the AEI article is a distortion of the UW policy and if you just read the headline you’d get a false view; however, AEI does make clear what Hansen’s actual argument is later on by quoting him.”

intellectual dishonesty on the part of AEI, nice to see we agree on something!

I think you need to distinguish between inflation and real price increases. I’ll take the Friedman view and see inflation as a monetary phenomenon. On the other hand, real prices increases are a function of the real economy. In the former case, wages will increase with prices. In the latter case, wages will not increase with prices. We are seeing the latter. Prices have increased in real terms, primarily for commodities either linked to oil or otherwise in demand by emerging market–chiefly Chinese–consumers. Gold is an example. Its price 4x that of ten years ago.

I think both the sets of numbers are right, but they are measuring different things.

In the former case, wages will increase with prices.

Could you expand on that?

Prices have increased in real terms, primarily for commodities either linked to oil

Do you have more information on that? I haven’t seen much suggestion that many commodity prices are linked to oil. Corn might be an important exception, though I’d argue that the explanation for the appearace of a link is that the US chose to replace direct farm subsidies with ethanol production requirements. The transition from direct farm subsidies to ethanol requirements caused a one-time sharp increase in US grain prices.

Steven, “(debt-) money” supply that grows in excess of production and returns to labor, and that flow increasingly to returns to financial capital, is “inflationary” and thus reduces over time the rate of growth of productive investment and production, as well as returns to labor, which in turn reduces the rate of growth of effective demand and eventually productivity and the trend rate of growth of the economy overall.

Since the early to mid-1980s, coincident with the fall from plateau of US crude oil extraction per capita, loss of goods-producing employment, and explosion in debt to wages and GDP, “money” supply grew at a cumulative differential rate to production, wages, and GDP that reached an order of exponential magnitude in 2008, the point at which debt had to grow at a super-exponential rate to production, wages, and GDP to avoid collapse. The debt-based system collapsed in 2008 right on schedule. The Fed printed over $3 trillion in bank reserves to fund deficit spending to prevent contraction of nominal GDP.

However, the vast majority of growth of “money” supply since 2008 has been in the form of 0% bank reserves, whereas bank loan and deposit growth has NOT increased since 2008. Production, employment, and real final sales per capita are no higher than in 2007-08, consistent with the growth of “money” supply ex bank reserves/bank cash assets. Velocity of “money” supply to private GDP remains below 1.0 and is again decelerating since Q3-Q4 2013, when “money” supply less bank reserves/cash began contracting (coincident with stall speed for GDP), as occurred in 1937-41 and three times in Japan since 1998, including recently, and similarly in the EZ today.

Also, financial profits now make up 50% of total profits (long-term average of 20%) and 4-5% of GDP (long-term average of 1%), resulting in net annual returns to the financial sector exceeding growth of nominal GDP, and cumulative imputed compounding interest to total credit market debt outstanding to average term is equivalent to 100% of US GDP, precluding any real growth of value-added output of the US economy after debt service.

Therefore, the Fed printing trillions in bank reserves and pumping up financial asset valuations without increasing returns to labor’s share of GDP only exacerbates the drag effects of rentier claims on wages, profits, GDP, and gov’t receipts, ensuring any net incremental gains to value-added output are already captured by the financial sector before they are realized elsewhere.

Menzie –

Another way to look at this would be to compare average nominal earnings to the CPI. The delta, in principle, should be “inflation” as perceived by the household. You could also look at milk, cheese or meat consumption per capita to get a feel for how households are perceiving daily prices.

I would do this myself, but I have other fish to fry today.

Steve Kopits wrote:

“I’ll take the Friedman view and see inflation as a monetary phenomenon.”

Steve,

One thing the Great Recession has taught is that Friedman’s sound bite is sorely lacking. Inflation is an expectations phenomenon. I am a Friedman fan but his monetary policy was simplistic QTM based on fallacious Fisher theory. In the light of day it simply does not hold up. Friedman made the same logical mistake as Keynes that QTM can drive an economy up or down without consideration of the productive side of the economy. Demand side models fail because they always stimulate over-consumption and malinvestment.

Morbius,

Your manufactured quote cannot is not found in any Austrian literature, not even the awful theories of Rothbard.

Banana,

Your comments on the lack of analysis of Mises demonstrates your ignorance of the subject. The quote above is from Human Action. Mises addresses your comments in hundreds of pages of analysis. Your ignorance could be cleared easily if you read HUMAN ACTION. My purpose of the quote was more to stimulate clear economic curiosity than to exhaustively answer questions. Here, the demand side failures are simply accepted as good economic theory yet not one adherent can point to a time in history when they have worked as advertised. The truth of Mises is proven almost daily from the failures of the Federal Reserve to the Japanese 25 year stagnation to US economic malaise.

Return to economic curiosity. Don’t let the politically correct technique of appeal to authority rather than logic drive your economic thinking. Be independent and think for yourself, but to do this you must learn the truth of the other side.

Ricardo: When you quote Mises, isn’t that “appeal to authority”. Shouldn’t you just be quoting Joe Schmoe on the street? Or just writing your own thoughts? — Why quote anybody else in the world if one knows as much as anybody else? Inquiring minds would like to know.

Re: the Austrian view on inflation, I think the Keynesians should cool their jets. The word “inflation” is a noun derived from “to inflate” which means to puff up with air. There was nothing devious or dodgy about von Mises’ use of it to mean an increase of the money supply. He simply used the word differently than we use it today. Keep in mind he first laid out his theory in 1912, before the word “inflation” in an economic context became practically synonymous with “consumer price inflation.”

What the Austrian theory actually says is that an increase in the money supply will lead to decreases in the value of money relative to other goods and assets, depending on who receives the money and how they use it. It’s actually a very logical and true statement, and generally comports very well with what we’ve seen – the money supply created additional demand for risky assets, and indeed, that was its explicit purpose as explained repeatedly by Bernanke himself.

The Austrian view that price changes depend on how money is used also explains why it was sensible in 2009-2010 to expect higher consumer price inflation than we’ve seen, because during that period money supply expansion was indirectly funding fiscal expansion.

If there’s a flaw with the Austrian theory on money supply inflation, it’s that at least in my reading it assumes that somebody must do something with additional money supply, when that’s not always the case – it can at least theoretically be hoarded unused.

As for contemporary Austrians predicting hyperinflation, complaints should be addressed to those people as I know of nothing in Austrian theory to support them. Hyperinflation is caused by extremely rapid fiscal expansion funded by monetary expansion, not by some moment of clarity when people suddenly realize their currency isn’t properly backed.

Interesting post. Tends to support Keynesian policy theory that suggests folks can be easily fooled and misunderstand real price levels.

My kitchen table theory to explain the above follows.

People don’t understand inflation but those who have taken business and economics courses do or claim to. Most people who have taken these courses are older so they would have been exposed to a simple classical quantity theory of money — Mv = PQ — and not much else.

These people expect inflation to increase because the monetary base is so great and so the money supply should be also very large.

The notion that inflation, measured and expected, can be divorced from money supply growth is new and relatively alien.

Once undergraduate business and economics students acquire the intellectual luggage to better understand contemporary inflation, inflation forecasts should improve. In theory, that new understanding will be communicated to people around a kitchen table.

Historically, higher and accelerating price inflation has been associated with wars (and gov’t borrowing and spending to supply military materiel), peak demographic cohorts coming of age, and associated supply-demand distortions to capital, consumer, and war-related goods.

See the historical literature on the Long Wave, i.e., Kondratiev Wave and the work of Schumpeter and neo-Schumpeterians since the 1970s-80s, including the effects on prices from Long Wave Peak War eras and the resulting subsequent reflationary debt cycles, e.g., Era of Good Feelings, Gilded Age, and Roaring Twenties, that were followed by debt-deflationary regimes in the 1830s-40s, 1880s-90s, 1930s-40s, Japan since 1998, and the rest of the world since 2008.

We are currently in a Late-Long Wave Downwave, Long Wave Trough debt-deflationary regime at a ~0% trend rate of real final sales per capita since 2007-08 vs. a long-term trend of ~2%, and a trend cyclical rate of real GDP of ~0.7%-1%. Real labor productivity around 1.5% and no growth of the labor force implies that the economy cannot withstand accelerating price inflation beyond 1.5-2% without contraction of profits and incomes after price changes and debt service.

The only way out historically is a 30-40% decline in debt to wages and GDP and a demand-side Long Wave Upwave era in which labor’s share of GDP increases to that of financial capital’s share. However, we are a LONG WAY from that at present. If or until that occurs, we are at stall speed and peak cyclical demand constraint and increasing risk of q-q annualized contraction or a “new-normal recession”.

Menzie,

Do you consider Mises an authority? Sorry, that is a surprise.

But in answer to your question I was taught Keynes and Friedman in economics in Grad school. They were illogical and my teachers were always perplexed by my questions even though I did not know a lot about economics at the time. In my search for answers to the unanswered questions (very similar to those confronting Bernanke and Yellen) I discovered Mises. When I started HUMAN ACTION I could not put it down. He started from how we can know what we know and then he developed a reasonable economics. So, no I do not appeal to authority when I quote Mises but to reason and logic.

Ricardo: Your authority, not mine.

Q: Have you ever heard of Boolean geometry?

Q2: Side question – why do you address Jim Hamilton “Professor”, and me “Menzie”. I am curious.

What I liked best about her article was her accusation that Steve Liesman making correct statements about Rick Santelli’s record is bullying.

These right-wing flacks really do know how to argue don’t they. Do anything to change the topic so nobody can actually see the facts..

actually that was one of the funnier parts of the exchange. if liesman was being a bully, what was santelli. it was like a 2 year old in a hissy fit! schlaes writes her article like santelli was some well behaved character in the exchange!