As noted by Jeff Frankel:

In terms of what the president can actually control to reduce inflation, one neglected tool is trade policy. Former President Donald Trump put these tariffs on aluminum and steel, and everything we import from China — all kinds of goods. The tariffs raise prices to consumers. It seems to me a no-brainer to undo those barriers. Biden should be able to get China and other countries to reciprocally lower some barriers against us. But with or without that, removing tariffs could bring down consumer prices and prices to businesses for steel and aluminum and all kinds of inputs immediately. That’s the one thing that the government could most rapidly control.

Relevant to the discussion of inflation, one of the things that differ between the 1970’s and the 2020’s is the openness of the US economy:

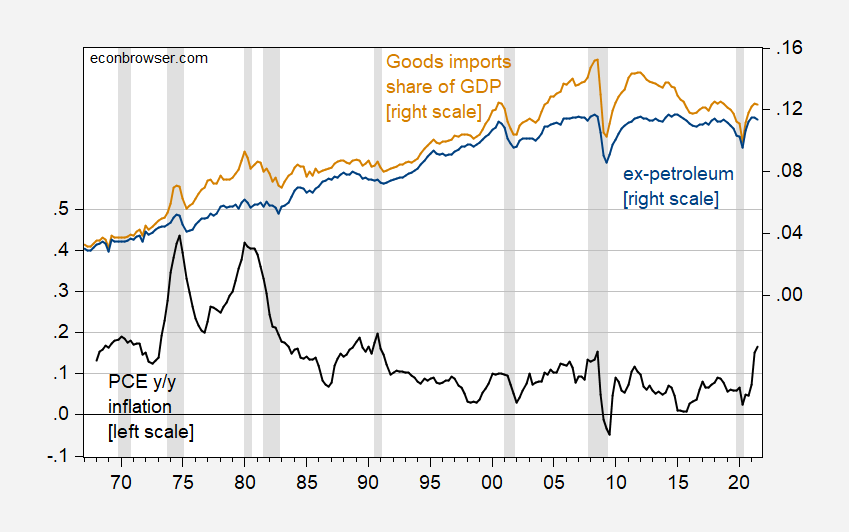

Figure 1: Personal consumption expenditure deflator inflation, year-on-year (black, left scale), and goods import share of GDP (brown, right scale), and goods ex-petroleum imports share of GDP (blue, right scale). NBER defined recession dates peak-to-trough shaded gray. Source: BEA 2021Q3 advance release, NBER, and author’s calculations.

Before inflation surged in 1974, non-oil goods imports were about 4.1% of GDP (1972Q3). Prior to the trade war, that ratio was 11.4% (2018Q1). While it’s not clear that external influences will always moderate inflation — after all prices could be rising faster in our trading partners (or it could be the shrinking world output gap now matters more), or the dollar could be depreciating. However, to the extent that one is not relying upon solely or mostly domestic suppliers, and foreign suppliers are exerting competitive pressures, openness would tend to reduce inflationary pressures. At least that’s more true if quotas and tariffs and combinations thereof are not limiting competitive pressures from abroad (see this post; it’s not a given that changes in import prices translate into broader price indices, but for iron and steel, it’s suggestive). See also Flaaen and Pierce (2019) for estimated impacts on producer prices arising from the 2018 tariff barriers.

To me, getting rid of the Section 232 tariffs, which were placed largely on US allies (and largely a gift to US steel firms), should be a no-brainer.

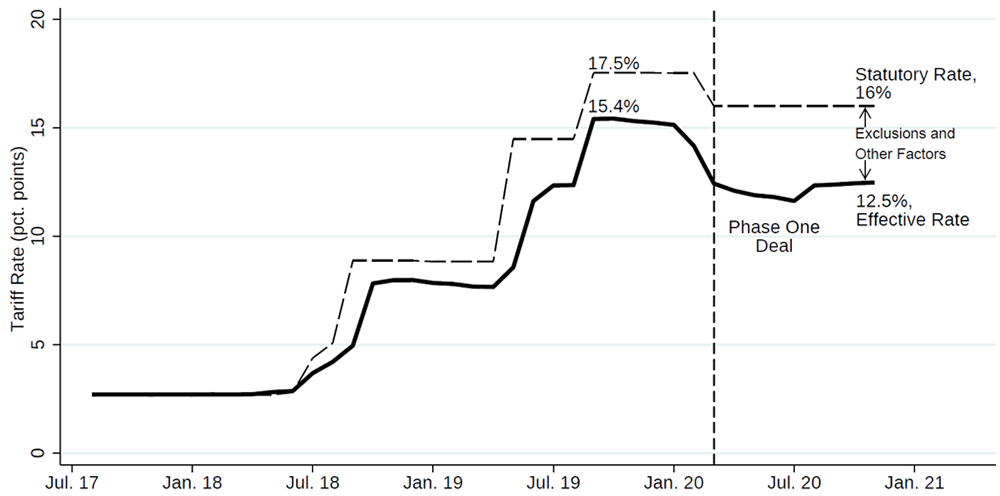

As an aside, here’s a interesting picture of effective tariff rates on imports from China, from Flaaen, Langemeier and Pierce (2021) (the new tariffs were Section 301 tariffs, since most of the iron/steel imports from China were already sanctioned under anti-dumping/countervailing subsidy measures).

Source: Flaaen, Langemeier and Pierce (2021)

A timely and interesting proposal but the owners of US Steel are not going to be happy that they have to face real competition. Expect another 8 hour rant from Kevin McCarthy on how such sensible ideas are taking us down the road to Communism.

Not so fast!

It isn’t just the owners of US Steel, it is also all their employees and all their stockholders and all the people in Minnesota and Michigan who work in mines and shipping and all the people who work in processing in Illinois and Indiana and Ohio and Michigan. And add in Cleveland Cliffs and Nucor, too…

The world is not just about greedy execs and innocent consumers. What one person pays is the earned living of another.

W: My guess is the biggest beneficiaries of the protection are the firms (including then the shareholders). Workers should gain relative to the non-tariff counterfactual. However, other workers downstream would lose. By the way, not all that one gains another loses. That is basic microeconomics, and in the case of tariffs, there is such a thing called a dead-weight loss. You might do well to look that concept up, as well as the basics of general equilibrium trade theory (heck, partial equilibrium will tell you the same thing).

I suggest that if you are unable to consult textbook, you read these lecture notes.

Cleveland Cliffs! Thanks for reminding us that the Trump DOJ allowed this firm to merge with AK Steel, which likely raised steel prices by limiting competition.

It’s hard to imagine that reducing Trump tariffs would have that much of an effect. The key is not to look at total goods imports, but only those imports affected—$200 billion, or 1% of GDP. A 25% tariff on those imports amounts to only 0.25% of GDP…hardly a major contributor to inflation. And that impact hit some time ago, well before the current surge in inflation.

https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2018/september/ustr-finalizes-tariffs-200

As we saw with all the ruckus about washing machine tariffs, which people buy only a couple times in their lives, it seems that economists like to fixate on fairly trivial effects…particularly when it comes to their sacred cow—“free” trade.

Don’t get me wrong. I think Trump’s tariffs were stupid.

I was wondering if liberal economists would finally get around to criticizing Biden for continuing policies that they had vehemently criticized Trump for. It looks like that day may be finally arriving. It would be a welcome end to a double standard of criticizing one person for a policy, while condoning the same policy by another.

With all your laser focus on the price of lumber, now you turn to looking at things in terms of national income aggregates? Care to tell us the weight of lumber in the overall price index?

BTW – me thinks Menzie and Jeff Frankel were sort of criticizing Biden for not ending those stupid tariffs by now. If they did not do it loudly enough for you – permit me to shout it from the roof tops.

I don’t care if they criticize Biden or not…but I do care about double standards from supposedly impartial sources. And I am concerned about hyping trivia.

BTW lumber is a significant part of the cost of building new houses, though housing price inflation is only beginning to be reflected in the CPI. And did you notice that lumber is now at 800, about double its price of two years ago…all this after we had repeatedly been reassured that the price was transitory. (To give a frame of reference, a recent obituary identified a deceased 25 year resident as a “transient.” My, my my…the meaning of words do es have a certain, charming flexibility, doesn’t it?)

With all that babbling – you managed to duck my question.

lumber was 600 in may 2018. it dropped below 500 twice in the past two years. you are not getting sustained inflation in lumber. you are getting supply chain spikes. that is why it is called transitory. housing starts are high compared to a few years ago. but they are at the historical trend for the last 50 years. that should be what is driving inflation, if anything. does not seem to be the case. supply chain issues seem to be the logical conclusion here.

Kevin Drum catches a few economists wondering if wages are sticky upwards:

https://jabberwocking.com/are-wages-sticky-upward/

As an inside during the internet computer technology (ICT) boom a generation ago, the demand for R&D workers soared. A lot of ICT firms decided not to increase their monetary compensation that much preferring to issue a lot of employee stock option (ESO) compensation. I will have to dig up the brilliant paper that explained by noting that if wages were increased substantially and the demand for ICT subsided, then downward stickiness of wages could be a problem. But the value of ESOs would readily decline.

While leaning pretty strongly to free and open trade, I’ll just say this: I believe there has to be reciprocation. Free trade for imports while blocked trade for exports is a FOOL’s game. And Menzie, Professor Hamilton, Professor Frankel, Professor Leamer of UCLA (all of whom I have great admiration and respect for) can show me any demand/supply curve they’d like. They’ll play hell getting me to believe otherwise. It’s like being on the playground and saying taking “free hits” to your shoulder will improve your boxing skills. It doesn’t add up.

How’s this for reciprocation: Reducing import duties guarantees the least well-off members of society – the ones who shop at Wal-Mart and Target because they have no other option – get a direct increase in their standards of living.

International trade doesn’t happen between countries; it happens between — and increasingly, within — companies. Odds are, those made-in-China consumer goods are made by foreign-invested companies.

That’s fair enough. But at what time point does your resident country no longer have the ability to make widgets/ Wal Mart products does that become more expensive long-term as a negative by-product of your resident country getting widgets 10cents cheaper the last 5 years?? Or just waiting on the one single input of “20 inputs” that you can’t get, to finish your “end product”??

Guess there’s no graph line for that…….. So…… we’ll just “forget that” as we can’t draw a graph line for it.

Moses Herzog at what time point does your resident country no longer have the ability to make widgets

Are you arguing against lifting tariffs or against globalization?

@ 2slugbaits

It’s not an “either/or” question. One can be pro international trade without consenting to be walked on. I could give an analogy related to being an advocate of healthy sexual intercourse and certain heinous crimes related to carnal activity. If I am against those violent crimes it doesn’t necessarily mean I am advocating celibacy. Hopefully without “triggering” any of Menzie’s readers you get the point.

Valid point, which would be be a topic for another discussion.

This one is about combating inflation, which in this context, is a relatively short-term issue.

Given that duties can be reimposed in a heartbeat, it seems to me that there should be no longer-term issues …. when dealing with inflation.

Wal-Mart, GAP, Nike etc. do source goods from China but they are often buying from 3rd party suppliers. Yes they have an affiliate in the Far East that does the sourcing and quality control. Note, however, that this affiliate is in some tax haven scheme often known as a Chinese Business Trust. Maybe Biden can have the IRS go after these transfer pricing schemes raising some actual tax revenue.

Now iPhone is made in China by a Taiwanese multinational called Foxconn for circa $250 even if you paid over $1000 to Apple who parks those profits in Bermuda. Did i say Biden should have the IRS go after that transfer pricing dodge?

Those Taiwanese, Hong Kong, Korean, Japanese, and yes, European and American, tax-dodging entities are outside the jurisdiction of the IRS. If they find a way to avoid paying high taxes in China, that’s their own affair.

Question: why would anyone want to jack up prices the least well-off have to pay?

OK, I’ll grant environmental concerns, and maybe one or two others, but those are topics for a different thread.

The tax rate in China = 25% and their tax authority is known for vigorous transfer pricing enforcement. The US should do so well.

But you miss my point. Take Skechers – which as a sketchy tax department. For every $1 billion in shoes sourced in China, sourcing costs $20 million but the US pays a tax haven $80 million, which pays the Chinese affiliate only $22 million. So this island entity with zero employees is parking $58 million in tax free income. I would argue both the US and Chinese authorities are being ripped off by this tax dodge.

Now if you see nothing wrong with this – you are not discussing this issue with any credibility.

‘It seems to me a no-brainer to undo those barriers. Biden should be able to get China and other countries to reciprocally lower some barriers against us.’

If China starts buying more of our soybeans, soybean prices in the US would go up even as China buys less for soybeans.

Now let’s assume does not reciprocally lower their tariffs. Some might fear the US would suffer a reduction in net exports. But isn’t the exchange rate floating? The dollar would devalue with respect to the yuan offsetting the negative net export effect how much would this undo this suggested reduction in inflation?

We need a good model and I’ve been out of touch so if you know of someone who has modeled this, that might make an interesting follow-up.

PGL strikes again with more meaningless word salad: “If China starts buying more of our soybeans, soybean prices in the US would go up even as China buys less for soybeans.

Now let’s assume does not reciprocally lower their tariffs….

We need a good model and I’ve been out of touch…”

Leave to CoRev to reject anyone actually modeling these issues out. After all CoRev has it easy – he just take verbatim instructions from Kelly Anne Conway and calls that his “analysis”. Good boy CoRev – Kelly Anne owns you a bone.

CoRev What’s your point? The benefits of tariff reductions are not conditioned on reciprocity. Reciprocity is the political figment of an uneducated electorate. Reducing tariffs makes the US better off irrespective of any nonreciprocity on China’s part. Your mental model of trade seems to be based on lessons you learned on the middle school playground. Time to grow up and wise up.

You expect CoRev to have a point? I thought you knew better than that.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/19/opinion/inflation-economy-supply-chain.html

November 19, 2021

Wonking Out: Going beyond the inflation headlines

By Paul Krugman

Early this year some prominent economists warned that President Biden’s American Rescue Plan — the bill that sent out those $1,400 checks — might be inflationary. People like Larry Summers, who was Barack Obama’s top economist, and Olivier Blanchard, a former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund, aren’t unthinking deficit hawks. On the contrary, before Covid hit, Summers advocated sustained deficit spending to fight economic weakness, and Blanchard was an important critic of fiscal austerity in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

But Summers, Blanchard and others argued that the rescue plan, which would amount to around 8 percent of gross domestic product, was too big, that it would cause overall demand to grow much faster than supply and hence cause prices to soar. And sure enough, inflation has hit its highest level since 1990. It’s understandable that Team Inflation wants to take a victory lap.

When you look beyond the headline number, however, you see a story quite different from what Summers, Blanchard et al. were predicting. And given the actual inflation story, calls for the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates to cool off the economy look premature at best.

First, overall demand hasn’t actually grown all that fast. Real final domestic demand (“final” means excluding changes in inventories) is 3.8 percent higher than it was two years ago, in an economy whose capacity normally expands about 2 percent a year:

https://static01.nyt.com/images/2021/11/19/opinion/krugman191121_1/krugman191121_1-jumbo.png?quality=75&auto=webp

Not that much of a demand surge.

It’s true that the Great Resignation — the unwillingness of many Americans idled by Covid-19 to return to the labor force — means that labor markets seem very tight, with high quit rates and rising wages, even though G.D.P. is still below its prepandemic trend. So supply is lower than most economists (including Team Inflation) expected, and the economy may indeed be overheated.

But everything we thought we knew from the past said that while overheating the economy does lead to higher inflation, the effect is modest, at least in the short run. As the jargon puts it, the slope of the Phillips curve is small. And those rising wages aren’t the main driver of inflation; if they were, average wages wouldn’t be lagging consumer prices.

So what is going on?

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=z21W

January 15, 2018

Shares of Gross Domestic Product for Private Fixed Nonresidential & Residential Investment Spending, Government Consumption & Gross Investment and Exports of Goods & Services, 2017-2021

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=z21I

January 15, 2018

Shares of Gross Domestic Product for Private Fixed Nonresidential & Residential Investment Spending, Government Consumption & Gross Investment and Exports of Goods & Services, 2017-2021

(Indexed to 2017)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=GyyX

January 15, 2018

Real Personal Consumption Expenditures for durable goods and services, 2017-2021

(Indexed to 2017)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=FMwl

January 15, 2020

Real Personal Consumption Expenditures for durable goods and services, 2020-2021

(Indexed to 2020)

https://cepr.net/skimpflation-the-latest-effort-to-hype-inflation-fears/

November 20, 2021

“Skimpflation,” the Latest Effort to Hype Inflation Fears

By Dean Baker

Yesterday I heard a piece * on NPR in which they highlighted “skimpflation.” This is where there is a deterioration in service quality, like long waits for service at a restaurant, which are not picked up in our standard measures of inflation. The implication is that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) is understating the true rate of inflation that people are seeing.

I had mixed feelings on hearing this report. On the positive side, I had made arguments like this a quarter century ago, when the party line (the views of the elites in both political parties) was that the official CPI overstated inflation.

The issue then was that there was a concerted effort to cut Social Security benefits. There is an annual cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) for Social Security that is tied to the CPI. The goal at the time was to reduce this COLA so that the government paid out less in Social Security.

The target was 1.0 percentage points. That may not sound like much, but the fall would accumulate through time. After ten years of getting 1.0 percent less each year, a retiree’s benefit would be 10.0 percent less. After twenty years, it would be 20.0 percent less. (The actual reduction would be somewhat less, due to the effect of compounding.)

Many of the big names in the economics profession were mustered together in the effort to cut Social Security benefits, with the Senate Finance Committee assembling the “Boskin Commission” to lead the charge. I was rather lonely in my efforts to question their assessment.

In addition to pointing out that much of the evidence that the CPI overstated inflation was weak, I also tried to call attention to ways in which it understated inflation. Some of these would fit the definition of today’s “skimpflation.” (Anyone interested can find this in my book, Getting Prices Right.) ….

ltr: Please edit your copying of articles to the essentials, rather than copying large portions (or even entire articles).

The articles I posted were portions only and the portions were important to my thinking however foolish my thinking may appear to be. I try very much to be helpful, for all my limitations, and will try harder.

I am grateful for all the assistance.

You are aware of copyright infringement laws?

Are you a lawyer for the NYTimes?

no. but i do have a digital subscription to the nyt. passing out content for free that others pay for is a bit problematic, don’t you think? it is interesting if somebody would take issue with copyright enforcement in a post that argues over tariffs and free trade. not to mention, ultimately prof chinn would hold responsibility for such material posted to his blog. segments are fine, to prove a point. but entire articles start to get into a slippery slope. online content will disappear if producers cannot recoup their costs.

Tariffs implemented were partially ignored and frankly mean little for inflation. Your take is simply wrong. With steel I would go further and regulate capital markets on overseas buying. Simply ending it and making business more nationalized. This is exactly what FDR did. Which gave labor a huge advantage.

GREGORY BOTT: What is this – argument by assertion? Could you provide just a little eensy teensy bit of analysis.

“Could” is very likely the problem. He couldn’t. So he doesn’t.

He sort of reminds me of CoRev’s minnie me.

Why not just unilaterally eliminate all tariffs in one stroke — aluminum, steel, fishing rods, leather gloves, Halloween costumes — all 5000 pages of them. It’s a wasteful nightmare of regulatory bottlenecks and useless manpower.

The tariffs seem to serve little purpose except as a tool for graft and corruption and political posturing and international saber rattling.

“The tariffs seem to serve little purpose except as a tool for graft and corruption and political posturing and international saber rattling.”

Which is exactly why Wilbur Ross and Mike Pompeo pushed Trump to implement these tariffs!

Trade restrictions are increasingly being used by the United States as strategic devices. Devices meant to limit technology applications and development in other countries. The Washington Post described this use of trade restriction in 2018, but it had already begun and has since become more pronounced:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2018/05/04/trump-is-asking-china-to-redo-just-about-everything-with-its-economy/

May 4, 2018

Trump is asking China to redo just about everything with its economy

By Heather Long – Washington Post

The Trump administration has finally presented the Chinese government with a clear list of trade demands. It’s long and intense (there are eight sections), and President Trump isn’t just asking Chinese President Xi Jinping for a few modifications. He’s asking Xi to completely change his plans to turn the Chinese economy into a tech powerhouse.

Noise, right? You’re scaling variables which themselves have huge error margins, by the magical GDP number which is itself half made up, so how can you get anything other than noise that you spin whimsical stories about?

Aren’t you in the faith business, really?

If your local weather forecast told you it was about to rain – I guess you leave the umbrella at home as the weather forecast did not mention the confidence intervals. How on earth do you ever even get out of the house with your obsession with noise?

pgl,

Well, just like the GDP estimates, evening weather forecasts are also “half made up.” Heck, if the numbers are made up, who cares about confidence intervals?

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/18/magazine/real-estate-memphis-black-neighborhoods.html

November 18, 2021

How the Real Estate Boom Left Black Neighborhoods Behind

While homeownership has been an engine of prosperity for white Americans, home values in places like Orange Mound in southeast Memphis have languished. What would it take to catch up?

By Vanessa Gregory

Paula Campbell’s house in the Orange Mound neighborhood of Memphis has a brick facade and neatly trimmed evergreens near the door. From the front yard, she can see across the street to her sister’s house, her daughter’s house and the little blue cottage her grandparents built more than 70 years ago. Campbell, who is in her 50s, with placid eyes and hair she often pulls into a ponytail, grew up on the block and moved away as a young woman. Although Orange Mound has changed in many ways since her youth, this stretch of Cable Avenue has always felt like home, and so 10 years ago she returned for good.

One dreary afternoon, Campbell walked around the corner of her garage, her cardigan hitched above her head against the rain, and gazed at the empty house next door. Mildew flecked the white sideboards and sagging carport; broken lawn furniture littered the yard, and a stray cat slunk through the weeds before disappearing beneath a tilting shed. Campbell and her husband, James, have twice tried to buy the decaying property — a house she lived in as a child — so they could clean it up. But they couldn’t persuade the absentee owner to sell. “I’ve taken pictures of it and sent it to code enforcement,” she said. She sighed and shook her head. “I’ll just keep doing it, keep taking pictures.”

The house next door is a symptom of a far bigger problem affecting Campbell and other homeowners in Orange Mound — one of the country’s oldest and most storied Black neighborhoods, a community where generations built homes and bet big on the American promise that homeownership would build prosperity. Despite a prime location near gentrifying midtown neighborhoods and the University of Memphis campus, Orange Mound’s property values plummeted by 30 percent from 2009 to 2019….

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=txCu

January 30, 2018

Homeownership Rate for White, Black and Hispanic, 2007-2021

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=BJDw

January 30, 2018

Homeownership Rate for White, Black and Hispanic, 2007-2021

(Indexed to 2007)

https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3458817.3487399

November 14, 2021

Closing the “quantum supremacy” gap: achieving real-time simulation of a random quantum circuit using a new Sunway supercomputer

By Yong (Alexander) Liu et al.

Abstract

We develop a high-performance tensor-based simulator for random quantum circuits(RQCs) on the new Sunway supercomputer. Our major innovations include: (1) a near-optimal slicing scheme, and a path-optimization strategy that considers both complexity and compute density; (2) a three-level parallelization scheme that scales to about 42 million cores; (3) a fused permutation and multiplication design that improves the compute efficiency for a wide range of tensor contraction scenarios; and (4) a mixed-precision scheme to further improve the performance. Our simulator effectively expands the scope of simulatable RQCs to include the 10X10(qubits)X(1+40+1)(depth) circuit, with a sustained performance of 1.2 Eflops (single-precision), or 4.4 Eflops (mixed-precision)as a new milestone for classical simulation of quantum circuits; and reduces the simulation sampling time of Google Sycamore to 304 seconds, from the previously claimed 10,000 years.

just remember, you are trying to compare 42 million cores to a 53 qbit quantum processor. quantum processors scale exponentially. so if you add one more processor to the 42 million cores, you get no increase. but if you simply add one more qbit, you go from 2^53 to 2^54 simultaneous calculations (this is a very rough description). one additional qbit doubles the capacity. every single time. it is a fools errand to try to chase quantum processors with a classical supercomputer. quantum processors cannot solve everything. but what they are immensely powerful for the things that they can solve.

So what does economic theory say about the US running a unilateral free trade policy?

1. Trade tends to equalize the price not only of traded goods and services but also of the factors involved in their production. That means we can expect wages to stagnate for as long as a large global wage disparity persists.

2. Free trade greatly incentivizes firms to relocate to low cost regions. Expect weak productivity as the owners of capital shift productive capacity to countries offering low wages, low taxes and minimal environmental controls.

3. Fiscal policy will become increasingly difficult as stimulus measures designed to enhance domestic activity are dissipated overseas. Problem is the expected domestic investment response is missing. Instead, a stimulus drags in more imports enhancing investment abroad. The result is simply more debt and a worsening balance of trade.

4. Although workers do poorly, the big winners in this scenario are the capital owners – those whose incomes depend directly or indirectly on holdings of shares or capital stock. Not only do they get the higher returns from investing in low cost regions abroad, they get enhanced returns domestically as capital becomes scarce locally. We can therefore predict rising inequality as wealth is increasingly transferred to the already wealthy. Unfortunately, they may use some of those resources to invest not in local productive capacity, but in fixed assets like land which merely exacerbates the plight of low income families facing higher rental and housing costs.

5. The U.S. (actually any developed economy) may over specialize, not through domestic inefficiency but simply due to a current imbalance in cost advantages globally. The best case scenario is that this causes industrial churn – industries disappear only to reappear when costs finally equalize. However, more recent models – gravity, new trade theory – may imply permanent loss (see below) .

6. Gravity models suggest the formation of industrial hubs which may mean the U.S. will permanently lose industrial capacity even when there is no longer a large cost incentive to produce abroad. Such hubs will house huge global conglomerates that dominate their respective sectors. Good luck any local business trying to compete with entities that can crush any competition. Industrial concentration on a global scale would almost certainly disadvantage workers in all countries as they exert a degree of monopoly power over wages and prices.

In short, poor quality jobs, low productivity, low growth, de-industrialization and rising inequality. Welcome to a globalized world.

Oh wait. Just heard I may be offered a directorship in a neoliberal “independent think tank”. Can I retract all the above?

I’m not sure how my argument about people who HAVE to buy the cheapest imports got derailed into “But, what about $85 sketchers,” but I’m going to go out on a limb here and say that the tax issue with Sketchers has nothing whatsoever to do with my point: stop penalizing the poorest among us, and fix the rest of the tax-dodging system.

And, while we’re at it, stop penalizing insignificantly small places where the government doesn’t spend massively beyond its revenues, just because other greedy governments can’t figure out how to finance their bloated armed forces and billionaire tax breaks.

What does the real world say about the US running a unilateral free trade policy?

1. Trade tends to equalize the price not only of traded goods and services but also of the factors involved in their production. That means we can expect the cost of living to be lower in wealthier economies than it would under protectionism for as long as a large (but shrinking) global wage disparity persists.

2. Free trade greatly incentivizes firms to relocate to low cost regions, thereby holding down the prices that must be paid by consumers. Productivity soars as as the owners of capital introduce modern technology, management know-how, and access to global markets. That’s why more open economies are politically more stable, and have higher standards of living than more closed ones.

3. Fiscal policy will need to shift to taxing passive income, as the base price of goods sold in the market is held at a lower-than-otherwise levels, making consumption taxes inadequate. The result is a less unequal levels of wealth.

4. Since workers do (comparatively) very well in export-oriented developing economies, and face much more moderate price increases in developed economies, the big winners in this scenario are broadly spread across the globe. Nationalistic protectionists hate this, because it benefits “other” people, too.

5. The U.S. (actually any developed economy) will specialize in intangibles such as brands, and patents, thanks to comparative advantage. The trade price of a plain white T-shirt is minimal, compared to the same T-shirt with a flash logo, and that computer is just a doorstop without useful software.

6. Gravity models suggest the formation of industrial, research, development, and marketing hubs (c.f. North Carolina) which may mean the U.S. will finally be able to shed ancient industrial capacity such as textile mills (c.f. North Carolina). Such hubs will house huge global conglomerates, miniscule start-ups, and everything in between, depending on what suits the needs of the owners and marketplace.

In short, poor quality jobs move from the developed world to the developing world (where they are good quality jobs); low productivity in the developing world dramatically rises; and low growth is replaced by faster progress in standards of living.

Welcome to a globalized world!

First, thanks for the respectful reply. Maybe a serious debate on free trade vs protectionism is possible. Let battle commence! I will take each of your points in turn as you did mine.

1. Free trade will lower the cost of living for the wealthier economies: Theoretical trade models typically show very poor outcomes for wages in developed economies. That means the cost of living will rise for wage earners and fall for rentiers (those whose income derives mainly from owning capital). So most will be worse off under free trade even though the rich will be considerably richer. It is an open question if the wealthy can be taxed sufficiently to compensate wage earners even given a political will to do so. There are simply too many ways for wealth to be held beyond the reach of domestic institutions.

2. Soaring productivity: Where? Not in any developed economy. Typically, productivity has fallen in the developed economies since the more protectionist era of the 50’s 60’s and 70’s. True, productivity has soared in some developing economies – mainly those employing sometimes highly protectionist and even mercantile policies to support growth. Please note, I do not approve of mercantilism – the deliberate engineering of export led growth by suppressing domestic consumption.

3. Sorry, cannot make any sense out of this reply. My point was that running an open economy makes fiscal stimulus difficult as the impact is dispersed globally. A serious problem for countries trying to get some real growth back into their economies after this and the last downturn. Central banks have done their bit by lowering interest rates to historically low levels, but even this has not persuaded investors to boost domestic investment in real productive capacity. That is why central banks seem relaxed about the current inflation, after years of trying to lift inflation into their target band (typically 2-3%) they are not about to get excited by an inflationary spike caused by an autonomous shock like a post covid stimulus.

4. Free trade benefits workers in developing economies. This is a serious point. Krugman wrote “In fact, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that growing U.S. trade with third world countries reduces the real wages of many and perhaps most workers in this country. And that makes the politics of trade very difficult.” But then goes on “So am I arguing for protectionism? No. Those who think that globalization is always and everywhere a bad thing are wrong. On the contrary keeping world markets relatively open is crucial to the hopes of billions of people.” Source: New York Times, Dec 28, 2007. The full article is worth a read. Curiously, I got it from N.Gregory Mankiw, Principles of Economics, 5th ed. Pg 192. I can promise you that if I accepted this then I would not advocate protectionism. My concern is that a globalized world will develop in a very unbalanced fashion that hugely advantages international wealth holders over all others. TNCs (transnational corporations) can drive costs lower by forcing a “race to the bottom” on taxes, worker safety, environmental standards and so on. Competition can be driven out by selling below cost or simply bought out. Beyond the reach of the laws of any one country, they will prosper even without being innovative or genuinely competitive. Almost a century ago, Keynes reached the same conclusion: “But experience is accumulating that remoteness between ownership and operation is an evil in the relations among men, likely or certain in the long run to set up strains and enmities which will bring to nought the financial calculation. I sympathize, therefore, with those who would minimize, rather than … maximize economic entanglement among nations.” J.M. Keynes, “National Self-Sufficiency”, The Yale Review, Vol. 22, no. 4, June 1933, pp. 755-769.

5. Developed economies will specialize in intangibles such as brands and patents. So, exactly how many U.S. workers will be suited to producing “intangibles”. Personally, I would prefer to see a greater variety of work opportunities than goods varieties. Manufacturing, in particular, offers a wide variety of different types of work – everything from manual labor to semi-skilled equipment maintenance to high end research and development. Will that textile mechanic who once took pride in fixing weaving machines be better or worse off in your specialized economy?

6. Exactly, the U.S. will doubtless be home to hubs that serve the interest of global conglomerates and their wealthy investors. Perhaps these will find new and innovative ways to increase their profit share. And your point?

Welcome to my world. Each country producing a broad range of goods and services using the latest technology. Sustainable, regional development. A level playing field able to foster competition. Strong environmental and worker safety laws that cannot be circumvented by removing production to locations which can be persuaded to relax them. I know – I’m dreaming again.

Floxo: Not sure I understand the assertion, free trade models usually imply negative outcomes for wage earners. Surely it must depend on the type of model (Heckscher-Ohlin vs. Ricardian) and the endowments that are assumed.

Thanks Menzie, that assertion needs a challenge. To clarify, I implied negative outcomes in models for labor in the “developed economies”. (For brevity, Home is a developed economy, Foreign a developing economy).

True, simple Ricardian models show labor in Home and Foreign gain (assuming both specialize). That is because labor is the only factor (a kind of default win for labor). However, more sophisticated Ricardian models that include capital can go either way. Even if we exclude Heckscher-Ohlin (HO) effects by creating a model in which both countries have the same relative factor endowments, labor can still lose if trade drives the home country toward the relatively more capital intensive good. Although, labor can also win if things go the other way.

However, HO models typically do show poor outcomes for labor at Home. A consequence of the Stolper-Samuelson theorem. Basically, trade will drive Home to focus on capital intensive goods, which lowers the labor share. Unfortunately for labor, the trade gain is not enough to compensate them for their loss. So the real wage falls.

Given a substantial advantage in relative capital abundance at Home and the ambiguous impact of Ricardian comparative advantage, I believe it is reasonable to expect a theoretical model to yield negative wage results for Home just on that basis.

But there is more. Even worse outcomes are predicted at Home if international capital mobility is factored in. Typically, Home faces a long term capital drain as productive capacity is transferred to Foreign driven by the higher rent caused by a relative scarcity of capital there. That implies reduced growth in GDP, productivity, business investment, a further hit to wages and rising inequality. (Party time for rentiers, they get increased returns from Foreign investment and increased returns at Home as capital is less abundant).

“Unrestricted foreign lending may lead to the more rapid growth of a country’s wealth, but it does this by putting off the day at which the workers in the country can enjoy, in the shape of higher wages, the advantages of the growing accumulation of capital.”

“Applied Theory of Money (Vol. 2)” J.M. Keynes, P. 312.

Obviously, I do not expect anyone to accept these ideas given the weight of contradictory opinion. Nevertheless, if allowed I will continue to assert my views – always based on theory.

Floxo,

Thanks for the courtesy. It can be rare around here.

Let’s not confuse wages with the cost of living; the latter is something with which everyone has to deal, including the unemployed, pensioners, students, and workers. Given how small the manufacturing sector is in the US (less than 6% of civilian employment are manufacturing production workers), the wage argument doesn’t hold water.

The day a farmer walks out of the field and into a workshop, his productivity soars. The day he transitions from workshop to factory, it soars beyond belief.

Your comment seems to suggest you are concerned about an eroding revenue base, which can easily be addressed by improving (not just increasing) taxation of passive income. Going after a shrinking sector of the economy is counter-productive.

Globalization is the opposite of nationalistic xenophobia. Either one cares about all people, or one doesn’t. Dividing the less-developed worker from the more developed worker is apartheid-like.

In an advanced society, bashing metal/wood/plastic with hammers to make stuff is very, very low productivity stuff. Unless, of course, you’re making prototypes or movie props, in which case it is the stuff of artisans. The US is overwhelmingly service oriented; let’s not pretend otherwise.

I totally disagree. Globalism is jet jumping capitalism and using mass migration as modern scabs. Xenophobic nationalism turns me into socialism eventually as capital markets die. You really don’t seem to understand slowing growth is structural and all you have left is debt. You can’t bring back past innovation rates the IR brought. The left hegelian movement was thus right in the end. It’s just now how now to proceed(and that is where the left hegelian movement split).

Wow, Gregory, you are deep. Of course the current debate over tariffs is ultimately about the split in the Left Hegelian movement. How insightful!

Barkley Rosser: Look, all we need is a synthesis, and we’re home free!

Menziw,

Actually, the funny thing is that there is a link to Hegelianism with debates about tariff policy, but, big surprise, Gregory has it off. It is an issue of the Right vs Left Hegelians, not the split within the Left Hegelians, which was over idealism versus materialism, which has nothing to do with either fascism, which Gregory claimed in the next thread, much less tariff policy.

So, the Right Hegelians were the super nationalists, viewing the Prussian and later German state as the ultimate Absolute. All must be subordinated to that. It is widely accepted by many, I mention Karl Popper as just one, that this philosophy was foundational to nationalist fascism and Naziism. This is a widely accepted standard view.

Anyway, an important German economist of the early nineteenth century who wrote about trade policy, was none other than Friedrich List, who famously supported Hamilton’s infant industry argument for protectionism. He saw this as supporting the building up of the Prussian state and advancing an industrial revolution within it. These were all positions of the nationalistic Right Hegelians, not of either faction of the Left (or “YOung”) Hegelians. And just to top things off, List knew Hegel and was a close ally of his, a real Hegelian in his own right, and definitely of the “Right” (or “Old”) nationalist persuasion.

Oh, and just to slam this home hard and to our current time, well, so protectionism has been part and parcel of hyper nationalist fascist policy coming out of Right/Old Hegelianism and Friedrich List’s view of how to build up the Hegelian Absolute Prussian (and later German) state.

So today likewise, while being protectionist does not automatically make one a fascist, fascists most definitely are protectionist, which makes it totally unsurprising that hyper nationalist Trump is a protectionist, although an incoherent and inconsistent one.

As a libertarian-leaning Republican, it was one of the things I liked about the 90s+ “neoliberal” Democrats…that they moved away from traditional protectionist leanings of 70s, 80s Democrats. And one of the things I disliked about Trump. This is not to say, that I like all of any of these hairy fookers…you have to be eclectic, like with music.

I’m concerned though. It’s really an easy thing rhetorically to be protectionist and interventionist. And in the oil business, people are definitely concerned about re-imposition of export controls, windfall profits, price controls, etc. from the 70s. Even if it never happens, it is already affecting current O&G investor sentiment (which is forward looking and must weigh possibilities, even if just a “chance”).

First, thanks for the correction. I should have said “the standard of living will fall for wage earners and rise for rentiers” rather than inaccurately state “the cost of living will rise for wage earners and fall for rentiers” – my bad. My point was that free trade may make the majority in a developed economy worse off than under a less open stance. That surely is a matter for concern. Such policies can lead to political instability and perverse outcomes. Perhaps the disgruntled majority will vote for some brainless chancer with just enough low cunning to sense their disatisfaction and make political capital out of it. Perhaps they will don high vis shirts and storm the streets. Or maybe vote to leave an important economic union in the mistaken belief that might help. Vaguely asserting their economic woes are for some greater global good reminds me of “let them eat cake”.

Look, here are my principle concerns:

Developed countries may suffer wage stagnation, low productivity, industrial churn, poor economic growth and rising inequality driven by trying to run open economies in a scenario where capital is internationally mobile.

The developing economies may experience equally poor outcomes as globalization favors the development of large industrial hubs in a relatively small number of locations. There are trade gains derivable from scale advantages but I believe the social costs outweigh them.

Globalization excessively advantages global corporations. Expect inequality to rise everywhere as they are able to drive up prices and drive down wages through sheer economic weight. We may end up with an aristocratic elite that owns the bulk of the world’s resources. The political instability that might arise from such distortions is, frankly, scary. It was that outcome that most worried Keynes when he decisively turned against globalization in his later years.

Contrast this scenario with a more closed approach. Any country willing to offer political stability and a business friendly environment will attract international firms that offer a wide range of goods and services. A firm might not want to source the good or service locally. They may prefer to source it in some remote location then ship it. But, if coerced, say by an appropriate tariff or quota, they will source locally. The outcome will be a world where economies experience similar patterns of growth and development. Where national standards of health and safety can be enforced. Where it is possible to tax profits because the income is sourced domestically. Where local firms can compete because all companies face similar domestic costs. Where workers are afforded a multitude of work opportunities whatever their respective talents.

Anon,

“ As a libertarian-leaning Republican, it was one of the things I liked about the 90s+ “neoliberal” Democrats…that they moved away from traditional protectionist leanings of 70s, 80s Democrats.”

On which planet?

JFK and LBJ trade policy was … GATT expansion, and leaving dollar:gold alone.

Nixon imposed the wage-and-price controls.

Reagan attacked imported cars.

NAFTA had a higher percentage of Republican representatives voting for it than Democrats.

“After much consideration and emotional discussion, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the North American Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act on November 17, 1993, 234–200. The agreement’s supporters included 132 Republicans and 102 Democrats. The bill passed the Senate on November 20, 1993, 61–38.[22] Senate supporters were 34 Republicans and 27 Democrats. Republican Representative David Dreier of California, a strong proponent of NAFTA since the Reagan Administration, played a leading role in mobilizing support for the agreement among Republicans in Congress and across the country.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_American_Free_Trade_Agreement

JFK died before 1970.

Yes, Nixon imposed wage and price controls. 70s were all screwed up. Still, he’s not a Goldwater republican.

I don’t think Reagan was a huge tariff guy. No politician bats a thousand…so fine…”car attacking”. And he did help get rid of natural gas price controls.

Anonymous: The Reagan administration’s most protectionist (in terms of dollar amounts) measures involved “voluntary export restraints”, on Japanese automobiles.

https://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/pa107.pdf

Your buddies at Cato note all the ways St. Reagan was a protectionist. Forget the rhetoric and check out the actual record.

Anon,

“ As a libertarian-leaning Republican, it was one of the things I liked about the 90s+ “neoliberal” Democrats…that they moved away from traditional protectionist leanings of 70s, 80s Democrats.”

On which planet?

JFK/LBJ trade policy was to expand GATT, the greatest exercise in freeing up trade ever attempted.

Nixon imposed wage-and-price controls, a la Cuba or China.

Nixon attacked auto imports.

I think you got your politics mixed up with your history.

He certainly got the Reagan record wrong. Even the Cato crowd got that (see provided link).

Floxo,

Run that by me again, will you?

How does a generally lower inflation environment … “ may make the majority in a developed economy worse off than under a less open.”

The opposite is true!

Less inflation for everyone!

“ Such policies can lead to political instability and perverse outcomes.”

Example, please (and not the oiliers), of more open societies being less stable than less open ones.

I’ll give you two contrary examples for every valid one you find.

“ some brainless chancer with just enough low cunning to sense their disatisfaction and make political capital out of it.”

Can we please leave He Who Shall Not Be Named out of this?

It unfairly undermines your entire point.

The UK leaving the EU had zero to do with “some greater global good,” and everything to do with a historic political blunder: the Conservatives had no thought of leaving the EU, but just sought to weaken Labour. Sort of like some GOPers and the last guy …really didn’t expect to win.

“ Developed countries may suffer wage stagnation, low productivity, industrial churn, poor economic growth and rising inequality driven by trying to run open economies in a scenario where capital is internationally mobile.”

Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia, Hong Kong, Macau, …

“ The developing economies may experience equally poor outcomes as globalization favors the development of large industrial hubs in a relatively small number of locations. There are trade gains derivable from scale advantages but I believe the social costs outweigh them.”

Germany, Sweden, Canada, USA (massively diversified), …

“ Expect inequality to rise everywhere as they are able to drive up prices and drive down wages through sheer economic weight.”

How’s that working out for the semiconductor industry? Any sign of that in phones, calculators, PCs, cars, or just about every consumer durable in the US household budget?

Here’s a graph of the price:performance ratio of computers: \

Note the sharp downward slope, over the past century.

Your final paragraph requires at least one — just one — real world example.

Otherwise, it is just xenophobic, protectionist fantasy.

Sorry!

It was Reagan who attacked auto imports, driving up the cost of driving for tens of millions of households, and giving us the tax dodging SUVs.

It was a lot more than those Japanese cars. Apparel quotas. Japanese electronics. Even sugar. Reagan was not quite Hoover but close.