The BLS reported on Friday that the U.S. unemployment rate fell all the way to 6.3% in April. That marks significant progress in terms of the bull’s eye of Fed accountability proposed by Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago President Charles Evans which Econbrowser discussed 2 months ago. The unemployment rate has dropped steadily over the last 4 years with no increase so far in the inflation rate.

Continue reading

Category Archives: Federal Reserve

“Risk Aversion, Global Asset Prices, and Fed Tightening Signals”

In the IMF analysis of capital flows highlighted in yesterday’s post, the VIX is used to proxy for risk. This variable has a lot of explanatory power [1] [2], but there is more to be investigated. Jan Groen and Richard Peck at the NY Fed examine the nature of risk in international financial markets, in a Risk Aversion, Global Asset Prices, and Fed Tightening Signals :

The global sell-off last May of emerging market equities and currencies of countries with high interest rates (“carry-trade” currencies) has been attributed to changes in the outlook for U.S. monetary policy, since the sell-off took place immediately following Chairman Bernanke’s May 22 comments concerning the future of the Fed’s asset purchase programs. In this post, we look back at global asset market developments over the past summer, and measure how changes in global risk aversion affected the values of carry-trade currencies and emerging market equities between May and September of last year. We find that the initial signal of a possible change in U.S. monetary policy coincided with an increase in global risk aversion, which put downward pressure on global asset prices.

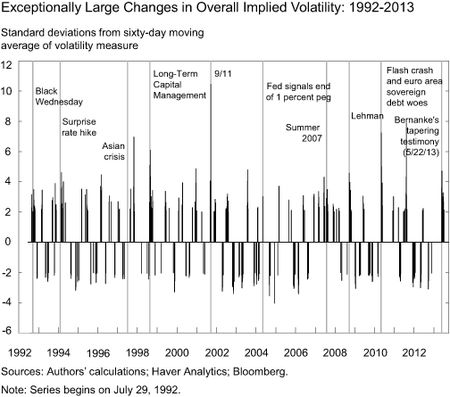

Implied volatility measures across different assets reflect, among other factors, market participants’ views on risk. Therefore, we conjecture that shifts in their risk aversion coincide with exceptionally large changes in implied volatility measures. An “exceptionally large” change in this case is defined as when overall implied volatility is at least two standard deviations above or below its mean over the previous sixty days. (“Overall implied volatility” is constructed as the average of the VIX index for U.S. equities, the Merrill Lynch Option Volatility Estimate [MOVE] Index for U.S. Treasury bonds, and the J.P. Morgan Global FX Volatility Index.) The chart below depicts changes in overall implied volatility for daily data from 1992 to September 2013, with labels for some key events that caused market turmoil. Exceptional volatility changes often occur in conjunction with these events, suggesting that these volatility changes are positively correlated with changes in (unobserved) risk aversion.

After examining the impact on the US dollar, carry trade returns and emerging market equity indices, the authors conclude:

Measuring changes to global risk aversion is a difficult exercise. The model used here suggests that substantial changes in risk aversion coincided with Chairman Bernanke’s May 22 testimony, resulting in substantial downward pressure on global asset prices in the two months after the May 22 testimony.

More in the post.

“Financial Adjustment in the Aftermath of the Global Crisis 2008-09: A New Global Order?”

That’s the title of a conference that took place at USC this weekend, co-organized by Joshua Aizenman, Menzie Chinn and Robert Dekle, and cosponsored by the USC Center for International Studies, USC School of International Relations, Journal of International Money and Finance, and the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

The effectiveness of unconventional monetary policy

Last week ECB President Mario Draghi revealed that the European Central Bank has been considering large-scale asset purchases as a tool to prevent European inflation from falling too far below the ECB’s target rate of 2%. What is the evidence for the effectiveness of these policies, and are there any risks?

Graphs of key economic trends

Here are some graphs of economic data that illustrate some interesting trends.

A bull’s-eye for Fed accountability

I was in New York on Friday attending the U.S. Monetary Policy Forum. One of the sessions was on how central banks could better communicate their plans for using unconventional monetary policy. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago President Charles Evans presented some very interesting ideas.

Fed Policy and Emerging Market Economy Vulnerabilities

The recent weakness in emerging market currencies, and implementation of the taper, are sure to be topics of discussion at the G-20 meetings in Australia. While the imminent retrenchment in quantitative/credit easing is responsible for some of the currency movements of late, I’m not sure this is the only way to look at recent events; nor do I think we need see a replay of previous episodes of currency crises in response to US monetary tightening.

Who anticipated the Great Depression?

Here’s the abstract from a paper by Doug Irwin in the February issue of the Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking:

The intellectual response to the Great Depression is often portrayed as a battle between the ideas of Friedrich Hayek and John Maynard Keynes. Yet both the Austrian and the Keynesian interpretations of the Depression were incomplete. Austrians could explain how a country might get into a depression (bust following a credit-fueled investment boom) but not how to get out of one (liquidation). Keynesians could explain how a country might get out of a depression (government spending on public works) but not how it got into one (animal spirits). By contrast, the monetary approach of Gustav Cassel has been ignored. As early as 1920, Cassel warned that mismanagement of the gold standard could lead to a severe depression. Cassel not only explained how this could occur, but his explanation anticipates the way that scholars today describe how the Great Depression actually occurred. Unlike Keynes or Hayek, Cassel analyzed both how a country could get into a depression (deflation due to tight monetary policies) and how it could get out of one (monetary expansion).

Guest Contribution: “Unemployment and Unnecessary U-turns in Forward Guidance”

Today we are fortunate to have a guest contribution written by Jeffrey Frankel, Harpel Professor of Capital Formation and Growth at Harvard University, and former Member of the Council of Economic Advisers, 1997-99.

Links for 2014-01-19

Quick links to a few items I found of interest.